Pandemic Data Sharing: How the Canadian Constitution Turned Into a Suicide Pact

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sars and Public Health in Ontario

THE SARS COMMISSION INTERIM REPORT SARS AND PUBLIC HEALTH IN ONTARIO The Honourable Mr. Justice Archie Campbell Commissioner April 15, 2004 INTERIM REPORT ♦ SARS AND PUBLIC HEALTH IN ONTARIO Table of Contents Table of Contents Dedication Letter of Transmittal EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................................1 1. A Broken System .....................................................................................................................24 2. Reason for Interim Report .....................................................................................................25 3. Hindsight...................................................................................................................................26 4. What Went Right?....................................................................................................................28 5. A Constellation of Problems..................................................................................................30 Problem 1: The Decline of Public Health ...............................................................................32 Problem 2: Lack of Preparedness: The Pandemic Flu Example..........................................37 Problem 3: Lack of Transparency.............................................................................................47 Problem 4: Lack of Provincial Public Health Leadership .....................................................51 Problem 5: Lack of Perceived -

Monday, May 25

MONDAY, MAY 25 14:20 – 15:50 CONCURRENT SESSIONS PHPC Ebola in Canada: What have we learned from this outbreak that we didn’t know before? PLAZA C, SECOND FLOOR MSPC The Ebola virus disease outbreak(s) in West Africa have raised several issues for public health and health care, especially with respect to infection prevention and control in health and other settings. The issues have ranged from world travel policy to personal protective equipment protocols. As with many similar public health events in the past (e.g., SARS, H1N1 influenza), the scientific foundations, valid and relevant surveillance data, estimates of risk and burden, effectiveness of interventions, principles and ethics, priorities and goals should provide the basis for evidence-informed, wise and fair decisions. These decisions may result in reaffirmation or change of policies, programs and practice and often have many consequences, including levels of preparedness and response, resource allocation, protocol changes, and specific education and advice for health practitioners and others working and living in the settings of everyday life. These, in turn, can be expected to affect attitudes and behaviour in society. What have we learned (or should we learn) from this outbreak that we didn’t know (or should have known) before? To address these issues from a knowledge translation perspective, panel members will provide the stimuli for interactive responses from the audience and other members of the panel for what promises to be an engaging and educational event. Learning Objectives: Describe the scientific, practical, political and ethical considerations for policy and program decisions for a low-probability, high- consequence public health event in Canada. -

2021-03-15 No Clear Significant Benefit to Lockdowns

Two minutes with the Justice Centre In other words, locking people down made no difference. No clear, significant Meanwhile in Ontario, one of the province’s former chief medical officers sent an open letter to Premier Doug Ford in benefit to lockdowns January, saying: “Lockdown was never part of our planned pandemic response, nor is it supported by strong science.” March 15, 2021 Dr. Richard Schabas had been Ontario CMO for ten years, and was personally involved with the 2003 SARS crisis, as chief of staff at York Central Hospital. Schabas wrote in support of North York MPP Roman Baber, who had been expelled from the Ontario Conservative caucus after writing to Ford that: “The lockdown isn’t working. It’s causing an avalanche of suicides, overdoses, bankruptcies, divorces and takes an immense toll on children.” Schabas noted Baber had been correct in his criticisms and in his call for an end to the Ontario lockdowns. Lockdowns are said to be necessary to slow the spread of Covid, so that health systems are not overwhelmed. “Lockdowns more lethal than Covid” -Dr. Modry Not everybody agrees the health system is in danger, however. In Alberta a highly qualified cardiovascular surgeon, Sometimes it seems a rational discussion of lockdowns is Dr. Dennis Modry, questioned Premier Kenney’s rationale for beyond Canadians. However, more and more the credible continued lockdowns in a December open letter. “We are voices are confirming what has been suspected from the start: nowhere close to overwhelming our healthcare system. As of Lockdowns don’t work and are actually harmful. -

2C. SARS I: the Outbreak Begins (March 13, 2003 - March 25, 2003)

Learningfrom SARS Renewal of Public Health in Canada . Learningfrom SARS Renewal of Public Health in Canada A report of the National Advisory Committee on SARS and Public Health October 2003 . i . The members* of the National Advisory Committee on SARS and Public Health were: • Dr. David Naylor, Dean of Medicine at the University of Toronto (Chair) • Dr. Sheela Basrur, Medical Officer of Health, City of Toronto • Dr. Michel G. Bergeron, Chairman of the Division of Microbiology and of the Infectious Diseases Research Centre of Laval University, Quebec City • Dr. Robert C. Brunham, Medical Director of the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control, Vancouver • Dr. David Butler-Jones, Medical Health Officer for Sun Country, and Consulting Medical Health Officer for Saskatoon Health Regions, Regina • Gerald Dafoe, Chief Executive Officer of the Canadian Public Health Association, Ottawa • Dr. Mary Ferguson-Paré, Vice-President, Professional Affairs and Chief Nurse Executive at University Health Network, Toronto • Frank Lussing, Past President and CEO of York Central Hospital, Richmond Hill • Dr. Allison McGeer, Director of Infection Control, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto • Kaaren R. Neufeld, Executive Director and Chief Nursing Officer at St. Boniface Hospital, Winnipeg • Dr. Frank Plummer, Scientific Director of the Health Canada National Microbiology Laboratory, Winnipeg (ex officio) * The Committee was materially assisted through corresponding members of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization. This publication can also be made available in/on computer diskette/large print/audio-cassette/Braille upon request. For further information or to obtain additional copies, please contact: Publications Health Canada Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0K9 SARS Tel.: (613) 954-5995 Fax: (613) 941-5366 ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2003 Cat. -

Dr Schabas Former on CMO Open Letter to Premier Ford Jan 18 2021

Dr. Richard Schabas, MD, MHSc, FRCPC January 18, 2021 Premier Doug Ford 111 Wellesley Street West Toronto, ON M7A 1A8 Dear Premier Ford: I served as Ontario’s Chief Medical Officer of Health from 1987 to 1997. I helped train many current medical officers, including Dr. Williams and was Chief of Staff at York Central Hospital during the 2003 SARS crisis. On January 15, 2021, MPP Roman Baber sent you a public letter calling on your Government to change course on Covid. MPP Baber made five key points and I believe he was correct on all five items. First, reasonable estimates of the infection fatality rate (IFR) from Covid have been declining as we learn more. Outside of Long Term Care, the risk of dying if you are infected with Covid is probably less than 0.2% overall and deaths are concentrated in the frail elderly. Younger people and healthy people have a much lower risk. Models that predicted hunreds of thousands of deaths from Covid in Canada were badly wrong because they used incorrect, exaggerated inputs. Second, lockdown was never part of our planned pandemic reponse nor is it supported by strong science. Lockdown has been used by almost every developed country and, in the great majority of cases, the lack of response speaks for itself. Two recent studies on the effectiveness of lockdown show that it has, at most, a small Covid mortality benefit compared to more moderate measures. Both studies warn about the excessive cost of lockdown. Third, there are significant costs to lockdowns – lost education, unemployment, social isolation, deteriorating mental health and compromised access to health care. -

Learning from SARS: Renewal of Public Health in Canada

Learningfrom SARS Renewal of Public Health in Canada . Learningfrom SARS Renewal of Public Health in Canada A report of the National Advisory Committee on SARS and Public Health October 2003 . i . The members* of the National Advisory Committee on SARS and Public Health were: • Dr. David Naylor, Dean of Medicine at the University of Toronto (Chair) • Dr. Sheela Basrur, Medical Officer of Health, City of Toronto • Dr. Michel G. Bergeron, Chairman of the Division of Microbiology and of the Infectious Diseases Research Centre of Laval University, Quebec City • Dr. Robert C. Brunham, Medical Director of the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control, Vancouver • Dr. David Butler-Jones, Medical Health Officer for Sun Country, and Consulting Medical Health Officer for Saskatoon Health Regions, Regina • Gerald Dafoe, Chief Executive Officer of the Canadian Public Health Association, Ottawa • Dr. Mary Ferguson-Paré, Vice-President, Professional Affairs and Chief Nurse Executive at University Health Network, Toronto • Frank Lussing, Past President and CEO of York Central Hospital, Richmond Hill • Dr. Allison McGeer, Director of Infection Control, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto • Kaaren R. Neufeld, Executive Director and Chief Nursing Officer at St. Boniface Hospital, Winnipeg • Dr. Frank Plummer, Scientific Director of the Health Canada National Microbiology Laboratory, Winnipeg (ex officio) * The Committee was materially assisted through corresponding members of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization. This publication can also be made available in/on computer diskette/large print/audio-cassette/Braille upon request. For further information or to obtain additional copies, please contact: Publications Health Canada Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0K9 SARS Tel.: (613) 954-5995 Fax: (613) 941-5366 ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2003 Cat. -

Queer Quarantine: Conceptualizing State and Dominant Cultural Responses to Queer Threats As Discursive Tactics and Technologies of Quarantine

Queer Quarantine: Conceptualizing State and Dominant Cultural Responses to Queer Threats as Discursive Tactics and Technologies of Quarantine by Péter Balogh A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Canadian Studies Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2015 Péter Balogh Abstract This study explores queer quarantine, my conceptualization of processes and practices aimed at assessing, diagnosing and isolating queer threats to the nation. In theorizing queer quarantine, I draw upon the longstanding conflation of queerness with disease and contagion, and build a case for reading the isolation, containment and casting out of queerness as an assemblage of discursive tactics and technologies aimed at quarantining queers beyond conventional understandings of quarantine. I examine the ways queers are imagined to threaten public space, healthy bodies, and the future of the nation, and provide a new accounting for so-called homophobic policies and practices deployed in statecraft and dominant culture. I also trace the emergence of the queer AIDS monster, an effect of disciplinary tactics of queer quarantine and a particular discursive formation in its own right. My study has two aims: building a case for queer quarantine and, at the same time, demonstrating how queer quarantine can be used as a new model of analysis to identify and explore some of the ways the Canadian state and dominant culture continue to marginalize and oppress queers despite the rights gains and “acceptance” that some gays and lesbians have achieved. My analysis reveals that in 1970s Toronto, the rapidly increasing visibility of queerness became a public threat necessitating tactical responses from local authorities and the police to quarantine queer spaces. -

Coronavirus (COVID‐19): Lessons Learned from SARS — a Guide for Hospitals and Employers Author(S): Michael Wa S, Susan Newell, Marty Putyra

Mar 5, 2020 Coronavirus (COVID‐19): Lessons learned from SARS — A guide for hospitals and employers Author(s): Michael Wa s, Susan Newell, Marty Putyra In this Update Lessons learned from the 2003 SARS outbreak and subsequent li ga on are key in understanding hospital and government obliga ons in the context of COVID‐19. Governments have an overarching public duty of care owed to the public at large, not a private duty of care to frontline hospital staff or pa ents. Hospitals have legal obliga ons during pandemics, including owing a private duty of care to their staff, personnel and pa ents. In light of conflic ng du es, hospitals must keep in mind the fiduciary duty to act in the best interest of pa ents and employees, and in par cular, the elevated duty of precau onary care, referred to as the “precau onary principle” in planning and taking all reasonable precau ons to protect staff. BACKGROUND The designa on of a novel coronavirus by the World Health Organiza on as a global public health emergency has captured headlines in 2020. As of March 3, 2020, there have been 33 confirmed cases of COVID‐19 in Canada with 20 in Ontario, 12 in Bri sh Columbia and one in Québec.[1] The interna onal spread of the virus (63 countries in addi on to Canada as of the me of wri ng) has unsurprisingly s rred memories of the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in Toronto and raised concerns regarding preparedness by hospitals, employers and all levels of government. -

A PANDEMIC of PANDEMIC HYSTERIAS • Bogus Models, Worthless Tests, Misreporting the Cause of Death

A PANDEMIC OF PANDEMIC HYSTERIAS • Bogus models, worthless tests, misreporting the cause of death. • A financial bonanza for the media and the pharma. • Unprecedented power for politicians. FREE OF COST IN PERPETUITY This is public domain project for the general education of the People BY Sanjeev Sabhlok, Ph.D. Economics (USA) Melbourne, Australia. Email: [email protected] • Resigned as Victorian Government economist in September 2020 to protest Police brutality and harmful policies. • Former senior civil servant in the Indian Government. • Author: The Great Hysteria and The Broken State – which describes the collapse of governance during this pandemic. With input from Irene Robinson (others are invited to help out) Please send any suggestions, corrections, improvements or other inputs to [email protected] PRELIMINARY SKETCH (NOT YET A DRAFT) 15 December 2020 1 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 WHY THIS BOOK .......................................................................................................................................... 5 1.2 RULE NO. 1: REAL PANDEMIC MUST LEAVE ITS SIGNATURE IN TOTAL ANNUAL DEATHS ............................................... 5 1.3 THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC THAT NEVER WAS – LET’S JUST CALL IT A FAKE PANDEMIC ............................................... 6 1.3.1 The covid “pandemic” has left no signature in total annual deaths ................................................. -

The Sars Commission Second Interim Report Sars And

THE SARS COMMISSION SECOND INTERIM REPORT SARS AND PUBLIC HEALTH LEGISLATION The Honourable Mr. Justice Archie Campbell Commissioner April 5, 2005 SECOND INTERIM REPORT ♦ SARS AND PUBLIC HEALTH LEGISLATION Table of Contents Table of Contents Dedication Letter of Transmittal INTRODUCTION AND EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................. 1 1. Medical Independence and Leadership ............................................................. 15 The Commission’s Earlier Findings and Recommendations..................................17 Chief Medical Officer of Health: What the Government Did ...............................22 Independence of the Chief Medical Officer of Health: Finishing the Task .........27 Power Over Assessors ..................................................................................................27 Public Health Laboratories...........................................................................................30 Enforcement Powers ....................................................................................................33 Powers over Inspectors ................................................................................................34 Powers to Remain with the Minister of Health and Long-Term Care..................35 Parallel Independence of Local Medical Officers of Health...................................38 A Continued Need for Greater Central Control over Health Protection.............41 Public Health Emergency Preparedness and Response...........................................46 -

SARS and Public Health Appendix 1

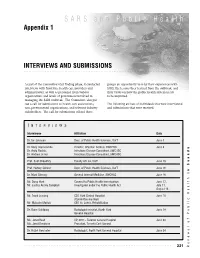

SARS and Public Health Appendix 1 INTERVIEWS AND SUBMISSIONS . As part of the Committee’s fact finding phase, it conducted groups an opportunity to relay their experiences with interviews with front-line health care providers and SARS, the lessons they learned from the outbreak, and administrators, as well as personnel from various their views on how the public health system needs organizations and levels of government involved in to be improved. managing the SARS outbreak. The Committee also put out a call for submissions to health care associations, The following are lists of individuals that were interviewed non-governmental organizations, and relevant industry and submissions that were received. stakeholders. The call for submissions offered these I NTERVIEWS Interviewee Affiliation Date Dr. Ian Johnson Dept. of Public Health Sciences, UofT June 3 Dr. Mary Vearncombe Director, Infection Control, SWCHSC June 6 Dr. Anita Rachlis Infectious Disease Consultant, SWCHSC Dr. Andrew Simor Infectious Disease Consultant, SWCHSC Prof. Sujit Choudhry Faculty of Law, UofT June 13 Prof. Harvey Skinner Dept. of Public Health Sciences, UofT June 16 Dr. Mark Cheung General Internal Medicine, SWCHSC June 16 in Canada Mr. Doug Hunt Counsel to Public Health Investigation June 17, Mr. Justice Archie Campbell Investigator under the Public Health Act July 11, August 18 Mr. Frank Lussing CEO York Central Hospital June 18 (Committee member) Mr. Malcolm Moffatt CEO St. John’s Rehabilitation Dr. Ronn Goldberg Radiologist-in-chief, North York June 19 General Hospital Ms. Janet Beed VP, COO – Toronto General Hospital June 20 Ms. Janet Davidson President, Toronto East General Dr. Raziel Gershater Radiologist, North York General Hospital June 24 . -

The Past, Present, and Future of Public Health Specialty Medicine in Canada

The Past, Present, and Future of Public Health Specialty Medicine in Canada Celebrating 40 years of Public Health & Preventive Medicine at the University of Toronto June 16, 2016 UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO Public Health & Preventive Medicine Residency Program Contents Our Program Page 2 Letters of Support Page 3 Leadership Page 5 Current Residents Page 11 Historical Exploration Page 12 Program Directors Page 22 Chief Residents Page 23 Graduates Page 27 Award Recipients Page 39 1 | P a g e University of Toronto Public Health & Preventive Medicine Residency Program The vision of the Public Health & Preventive Medicine Residency Program at the University of Toronto is to be a great place to learn and a great place to teach Public Health Specialist Medicine to improve health and contribute to society in Canada and globally. Our mission is to train public health physician leaders and to graduate Public Health and Preventive Medicine specialists who possess the knowledge, skills and values to make independent, evidence-informed, community responsive, accountable and ethical decisions to assess, maintain and improve health overall and reduce health inequities in communities and populations. While our program emphasizes the skills and knowledge needed serve as local medical officers of health, it also prepares trainees for Public Health and Preventive Medicine specialist roles in research, education and practice in a variety of government, academic and non-government settings at the national, regional, local and global level. The program also supports trainees to gain clinical certification in Family Medicine and to explore synergies at intersection of clinical medicine and public health. Our program was founded by Dr.