Wright's Studio, Chiseled Into a Former Quarry—The Heart of a Healed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Town of Philipstown Planning Board

Town of Philipstown Planning Board Meeting Agenda Butterfield Library, Cold Spring, New York 10516 July 30, 2015 7:30 PM Public Hearing VISTA44 LLC (dba Garrison Cafe) Pledge of Allegiance Roll Call Approval of Minutes: June 18, 2015 VISTA44 LLC (dba Garrison Cafe) - Application for major site plan - 1135 Route 9D, Garrison, NY: Submission of revised plans/discussion Gex - Lot line change - 24 Hummingbird Lane, Garrison, NY - Request for extension Manitoga - Special Use Permit #188 - 22 Old Manitou Road, Garrison, NY: Update Adjourn Anthony Merante, Chairman Note: All items may not be called. Items may not always be called in order. PhilipstQwn Planning Board Public Hearing - July30, 2015 The Philipstowll Planning Board for the Town of Philipstown, New York will hold a public hearing on Thursday, July 30 at 7:30 p.m. at the Butterfield Library on Morris Avenue in Cold Spring, New York to consider the following application: VISTA44 llC dba Garrison Cafe - Application dated June 4, 2015, for a major site plan approval. The application involves two adjacent parcels along the west side of NYS Route 90, immediately south of Grassi Lane. The northerly parcel is currently developed with two commercial buildings, while the southerly parcel is residentially zoned. The applicants currently operate the Garrison Cafe in a portion of the southerly building on the commercial site. The remainder ofthis building contains.a 3 bedroom apartment, which is currently unoccupied. The applicant seeks approval to expand the cafe to the north into a portion of the apartment where it will operate a wine bar and provide additional and more formal dining facilities. -

Wright, Russel, Home, Studio and Forest Garden; Dragon Rock (Residence)

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMBNo. 1024-0018 MANITOGA Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Fonn 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Manitoga Other Name/Site Number: Wright, Russel, Home, Studio and Forest Garden; Dragon Rock (residence) 2. LOCATION Street & Number: NY 9D Not for publication: City/Town: Garrison Vicinity: State: New York County: Putnam Code: 079 Zip Code: 10524 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): _ Public-Local: _ District: _X Public-State: _ Site: _ Public-Federal: Structure: _ Object: _ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 2 _J_ buildings 1 0 sites 0 0 structures 0 0 objects 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 3 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: Hudson Highlands Multiple Resource Area Designated a NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK on FEB 1 1 2006 by the Secretary of the Interior NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) 0MB No. 1024-0018 MANITOGA Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

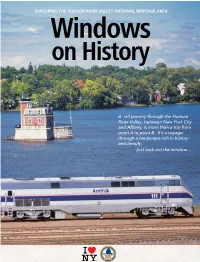

Windows on History

EXPLORING THE HUDSON RIVER VALLEY NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA Windows on History A rail journey through the Hudson River Valley, between New York City and Albany, is more than a trip from point A to point B. It’s a voyage through a landscape rich in history and beauty. Just look out the window… Na lley tion Va al r H e e v r i i t R a g n e o A s r d e u a H Na lley tion Va al r H e e v r i i t R a g n e o A s r d e u a H W ELCOME TO THE HUDSON RIVER VALLEY! RAVELING THROUGH THIS HISTORIC REGION, you will discover the people, places, and events that formed our national identity, and led Congress to designate the Hudson River Valley as a National Heritage Area in 1996. The Hudson River has also been designated one of our country’s Great American Rivers. TAs you journey between New York’s Pennsylvania station and the Albany- Rensselaer station, this guide will interpret the sites and features that you see out your train window, including historic sites that span three centuries of our nation’s history. You will also learn about the communities and cultural resources that are located only a short journey from the various This project was made station stops. possible through a partnership between the We invite you to explore the four million acres Hudson River Valley that make up the Hudson Valley and discover its National Heritage Area rich scenic, historic, cultural, and recreational and I Love NY. -

Section 1: Comprehensive Planning Process

Philipstown Comprehensive Plan 2006 CHAPTER 1 / BACKGROUND Section 1: Comprehensive Planning Process This Comprehensive Plan is the product of a five-year process in which the residents of Philipstown came together to agree upon a common vision for their future, and the Comprehensive Plan Special Board shaped that vision into this action-oriented document. Over the five years, numerous meetings and two public hearings were held, giving residents many opportunities to offer and respond to ideas and suggestions. This Plan is the culmination of a significant effort by many citizens of Philipstown working together to express who we are and what we want for our future. Although a professional planning consultant provided assistance, this Plan was written by the community and for the community. The process began when the Town Board commissioned a "diagnostic" planning study of the Town by planning consultant Joel Russell. That study, completed in October, 2000, reviewed the 1991 Town Master Plan, and recommended that the Town prepare a more citizen-based comprehensive plan which would be concise and readable, "a new planning document that clearly expresses a set of shared goals and principles." The first step in developing this plan was a town-wide forum bringing a cross-section of the community together to define consensus goals and action strategies to accomplish them. This forum, Philipstown 2020, was held over two and a half days in April, 2001. More than two hundred residents participated. "Philipstown 2020: A Synthesis" (see Appendix A) expresses the outcome of this forum, and its goals were the starting point for preparing this Plan. -

George Nakashima Woodworker Complex NHL Nomination

NATIONAL IDSTORJC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Fonn I 0-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Fonn (Rev. 8-86) 0MB No 1024-0018 GEORGE NAKASHIMA WOODWORKER COMPLEX Page 1 United States De ~,mncnt of the Interior. National Park Service National Re ister of Historic Places Re istration Fonn 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: George Nakashima Woodworker Complex Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 1847 and 1858 Aquetong Road Not for publication: City/Town: Solebury Township Vicinity: State: Pennsylvania County: Bucks Code: 017 Zip Code: 18938 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: .x_ Building(s): _K_ Public-Local: District: Public-State: Site: Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing ..lL -1.. buildings sites -1.. structures _ objects _l2_ -1.. Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: -12 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: Nakashima, George, House, Studio & Workshop Deelgnated a National Historic Landmark by the Seoretary of the Interior NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 GEORGE NAKASHIMA WOODWORKER COMPLEX Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

A Catalyst for Community Preservation

A CATALYST FOR COMMUNITY PRESERVATION Preserve New York, a signature grant program of the New York State Council on the Arts (NYSCA) and the Preservation League of New York State, made possible with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature Impact Study, 2005-12 Report Compiled September 2016 A CATALYST FOR COMMUNITY PRESERVATION Preserve New York, a signature grant program of the New York State Council on the Arts (NYSCA) and the Preservation League of New York State, made possible with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature Impact Study, 2005-12 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction and Overview 2. Key Findings, Part I – General Information 3. Key Findings, Part II – Project Funding Information & Implementation 4. Key Findings, Part III – Implementation & Data for Historic Structure Report Projects 5. Key Findings, Part IV – Implementation & Data for Cultural Landscape Report Projects 6. Key Findings, Part V – Data and Follow-Up For Cultural Resource Survey Projects 7. Conclusions 8. Preserve New York Case Studies (with index, by project type) 9. Master Index of Grants Awarded 2005-2012 and included in study data *Images on cover page (top, left to right): South Wedge Historic District, Rochester (South Wedge Planning Committee, 2011), Wallabout Historic District, Brooklyn (Myrtle Avenue Revitalization Project, 2011), Madison Lewis Woodlands (Village of Warwick, 2007) *(Bottom, left to right): Manufacturing Buildings on River Street (City of Troy, 2012), Elmwood West Historic District (Preservation Buffalo Niagara, 2011), Recent Past Resources in Rochester’s Central Business District (Landmark Society of Western New York, 2008) Introduction & Overview The New York State Council on the Arts and Preservation League of New York State began Preserve New York as a partnership grant program in 1993. -

See Our Complete Project List

PLANNING & IMPLEMENTATION PROJECTS LIST Founded in 1987, Heritage Landscapes is a small, high-quality firm providing professional consulting in preservation landscape architecture and planning for historic communities and properties of various types and scales. Projects may address city-wide or regional heritage assets, or specific properties such as cemeteries, historic sites, museums, national parks and monuments, capitols, modern landscapes, private properties, campuses, botanical gardens, arboreta, battlefields, military sites, park systems, parkways, and parks. Our project list is organized into headings, demonstrating the range of Heritage Landscapes' expertise in planning, implementation, management, maintenance, and interpretation of varied cultural landscapes. In this list, the project and location are followed by the original design professionals and/or development period. In order to avoid repetition, the role of Heritage Landscapes is assumed as project leader with subconsultants credited. When we serve as landscape preservation subconsultants, the project lead is listed and our role noted. Multiple projects for a single historic landscape are indicated by title and date. Projects are arranged with current work first, in reverse chronological order, by topic. CAPITOLS, CIVIC & ACADEMIC CAMPUSES AOC Capitol Square Trees, Washington DC, provide future planting plan to replace Olmsted trees, 2021; preservation landscape architects; for Capitol Grounds Superintendent and Urban Forester. AOC Senate Office Buildings Cultural Landscape Report, Washington DC, Russell, Hart, Dirksen and Senate Pages building grounds, streetscapes and surface parking, 2021, through AECOM contract; US Cost, estimators; for the Architect of the Capitol. US Chief of Mission Residence, Paris, France; listed historic garden; preservation landscape architects for building renovation project, flood protection and related landscape issues, 2021; team lead Krueck + Sexton Architects, for Department of State Overseas Building Office. -

Saving Ethel Rosenberg His Mother Was Executed As a Spy

[FREE] Serving Philipstown and Beacon Happy New Year! Last-minute tax deductions See Page 10 December 30, 2016 161 MAIN ST., COLD SPRING, N.Y. | highlandscurrent.com From Barges to 'Bombs' Following angry reaction to oil ships, feds seek feedback on trains By Liz Schevtchuk Armstrong hree weeks after the Coast Guard closed public comment on a pro- Tposal to add 10 anchorage sites for oil barges on the Hudson River, including a site between Beacon and Newburgh, the U.S. Department of Transportation is ask- ing for feedback on proposed restrictions on trains that carry oil along its shore. The comment period opens Friday, Dec. 30 and continues through Feb. 28. New York has pushed for stricter regu- lation of the oil trains, often derided as “bomb trains” because of their potential explosive power. In neighboring Quebec, a 2013 oil-train accident triggered an ex- plosion and fire, killing 47 people and de- A summer scene at Garrison's Landing Photo by Mike Enright stroying part of a village. Working through its Pipeline and Haz- ardous Materials Safety Administration, Finally, New Life for Guinan’s? DOT wants public input as it considers After nine years of shadows, plan in place Garrison Station Plaza has whether to establish limits on the vapor a building permit in hand pressure of hazardous fuel shipped by to reopen Garrison’s Landing site for what it hopes will be rail. Higher vapor pressures contribute to the final stages of arrang- crude oil’s volatility and flammability. By Alison Rooney ing financing. DOT published its notice in November, The many people who nearly a year after New York Attorney fter nine years of sitting empty, the building that housed visit Garrison’s Landing General Eric Schneiderman petitioned the Guinan’s Country Store for more than 50 years before it and are charmed by its agency to limit vapor pressure to less than Aclosed in 2008 may reopen soon as a café operated by historic character and 9 pounds per square inch (PSI). -

Nearby Hiking Trails

blazed trail heads south, there are a few short side trails overlooking the river. Continue to follow the blazes to leading to the water’s edge with more views west across the gazebo overlooking the Hudson River, a nice spot for the river. Near the southern tip of the point, at 0.4 miles, a break. Exit the gazebo to the north down the path to the red-blazed trail makes a sharp left turn. Bear right a woods road that is part of Marcia’s Mile indicated by and continue ahead on a wide path (no blazes) to a rock blazes. Left takes you to Arden Point and the Garrison outcrop with a bench, at the southern end of the point, Train Station. Nearby Hiking Trails which affords a panoramic south-facing view, with the To return to the beginning of the loop, follow Marcia’s Bear Mountain Bridge in the distance. From this point, Mile as it goes right (south) and takes an immediate left. Arden Point & Marcia’s Mile follow a wide woods road north a short distance back to The trail then takes another sharp left into the woods. (easy, 2.2 mi., 1.5 hr. from start to finish) the railroad bridge. Cross the bridge, turn right (south) Follow the markers closely as they ascend a hill, go straight A hike around a magnificent promontory to a gazebo with onto the white-blazed Marcia’s Mile trail and walk up the for a short while, and then take a hard right, cross a field views of the Hudson River. -

PDF Guidebook

LOWER HUDSON Manitoga: Russel Wright Estate http://www.russelwrightcenter.org/rwmanitoga.html 584 Route 9D PO Box 249 Garrison, NY 10524 Hours: Monday - Friday at 11am; Saturday and Sunday at 11am and 1:30pm Advance reservations required for weekend tours due to limited space. Group Tours are available by appointment only. Please contact the office during Manitoga regular business hours to reserve space. Phone: 845-424-3812 Fax: 845-424-4043 Historical Description: "In the 1930’s, 40’s and 50’s Wright was one of the best known designers in the U.S. At the apex of his career, Wright left New York City and moved his base of operations to Garrison. It was here that he created a unique home and designed landscape. He named it Manitoga, meaning Place of the Great Spirit in Algonquin. Wright shared the Native Americans' respect for the earth." The Site: "Wright purchased Manitoga in 1942 and once it became his permanent residence he came to know the plants, rocks, soils, water, climate, and creatures comprising the site, and the successional process that would ensue. It was these that he manipulated, perhaps edited. Some species, exotic and invasive, he removed; others he managed for light and shade. Certain species he introduced, notably wildflowers; others, ferns and mosses, he cultivated. In this process, RW identified certain locations that offered dramatic experiences or views. They in turn were linked by the pathway system, which did much to demonstrate the richness and natural history of the site." Directions: The public entrance to Manitoga is located in the heart of New York's Hudson Highlands, 50 miles north of Manhattan in Garrison, NY. -

Janet Stapleton for Immediate Release IVY BALDWIN DANCE

Janet Stapleton 234 West 13th Street #46 New York, NY 10011 212.633.0016 / [email protected] For Immediate Release IVY BALDWIN DANCE AND MANITOGA PRESENT THE PREMIERE OF QUARRY, SEPTEMBER 21–22, 2019 New York, NY, July 8, 2019 – On September 21 and 22, Ivy Baldwin Dance will present Quarry, a site-specific performance work at Manitoga, the former home and 75-acre woodland garden of the late American industrial designer Russel Wright. Quarry takes inspiration from Wright’s desire to blur lines between outside and inside, nature and the man-made, and from his deep commitment to experimentation with form and material. It is vital to Baldwin at this moment in history to examine the arc of humans’ relationship to nature, and, through Quarry, to contextualize the lessons of Wright himself. She writes, “Long before climate change was a presence in every conversation, Wright lived a metaphor in miniature by confronting and resuscitating a ravaged landscape, integrating thoughtful architecture and the loving restoration of its native surroundings.” At its fall premiere, Quarry will magnify Wright’s vision and Manitoga’s dramatic variations on scale and intimacy as the audience experiences the property and performers from great distances, overlooking the quarry, viewing dancers on mossy roofs, and following smaller performances into the surrounding woodlands. Quarry is choreographed by Ivy Baldwin and features performances by Katie Dean, Kay Ottinger, Kayvon Pourazar, Tara Sheena, Eleanor Smith, Saúl Ulerio, Katie Workum, and Baldwin. Music composition and sound installation is by Baldwin’s longtime collaborator Justin Jones. With costume design by Mindy Nelson and set design by Michael Drake and Baldwin. -

Trail Walker Fall 2014

10 Great Trail Projects! This Invasive Our crews have been Could Blind You out building and And it’s in our area. Learn how improving trails for you. to recognize giant hogweed. READ MORE ON PAGES 6—7 READ MORE ON PAGE 9 Fall 2014 New York-New Jersey Trail Conference — Connecting People with Nature since 1920 www.nynjtc.org Trail Conference Recommendations Kaaterskill for Protecting Kaaterskill Falls and PEOPLE FOR TRAILS the Public Falls Deserves The Trail Conference is recommending a comprehensive and collaborative approach Safe Access to managing public access at Kaaterskill Falls, with the goals being to increase safety wo deaths this season, both the and access while protecting and improving result of falls from water-slicked this unique and popular natural resource in Trocks. Unsafe trailhead access, with the Catskill Park. pedestrians and vehicles competing for Solutions will require the cooperation of pavement on a winding, narrow road. the Town of Hunter, the DEC, Dept. of Social paths on the mountainside that result Transportation, nearby landowners, non- Daniel Yu in widespread erosion, degrading both the profit organizations like the Trail Staten Island, NY mountain and the experience for hikers. Conference, and local businesses. The Trail These are just some of the problems that Conference supports: Komodo Dragon: Daniel’s afflict the popular Kaaterskill Falls, an icon - • The creation of a weekend shuttle serv - bestowed nickname at the ic natural feature of the Catskill Park and ice to reduce parking pressure in the clove; Bear Mountain project. the Hudson River School of art. This sum - • Improvements to pedestrian safety mer, the Trail Conference joined New York along Route 23A; Why? Daniel approaches the art State Senator Cecilia Tkaczyk, local offi - • Improvements to the current Kaater - of building cribwall much as a cials, and representatives of the Dept.