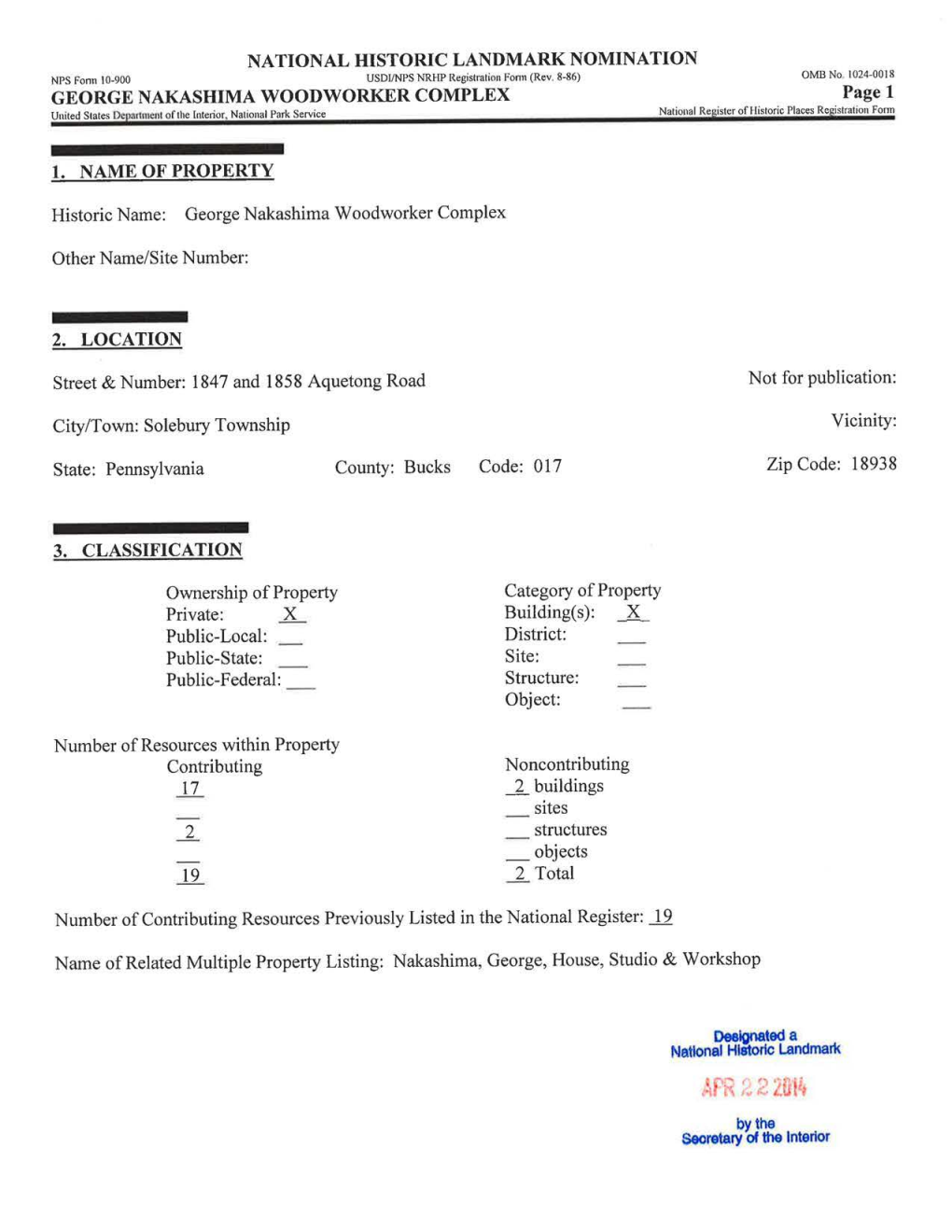

George Nakashima Woodworker Complex NHL Nomination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graphic Recording by Terry Laban of the Global Health Matters Forum on March 25, 2020 Co-Hosted by Craftnow and the Foundation F

Graphic Recording by Terry LaBan of the Global Health Matters Forum on March 25, 2020 Co-Hosted by CraftNOW and the Foundation for Advancement of International Medical Education and Research With Gratitude to Our 2020 Contributors* $10,000 + Up to $500 Jane Davis Barbara Adams Drexel University Lenfest Center for Cultural Anonymous Partnerships Jeffrey Berger Patricia and Gordon Fowler Sally Bleznack Philadelphia Cultural Fund Barbara Boroff Poor Richard’s Charitable Trust William Burdick Lisa Roberts and David Seltzer Erik Calvo Fielding Rose Cheney and Howie Wiener $5,000 - $9,999 Rachel Davey Richard Goldberg Clara and Ben Hollander Barbara Harberger Nancy Hays $2,500 - $4,999 Thora Jacobson Brucie and Ed Baumstein Sarah Kaizar Joseph Robert Foundation Beth and Bill Landman Techné of the Philadelphia Museum of Art Tina and Albert Lecoff Ami Lonner $1,000 - $2,499 Brenton McCloskey Josephine Burri Frances Metzman The Center for Art in Wood Jennifer-Navva Milliken and Ron Gardi City of Philadelphia Office of Arts, Culture, and Angela Nadeau the Creative Economy, Greater Philadelphia Karen Peckham Cultural Alliance and Philadelphia Cultural Fund Pentimenti Gallery The Clay Studio Jane Pepper Christina and Craig Copeland Caroline Wishmann and David Rasner James Renwick Alliance Natalia Reyes Jacqueline Lewis Carol Saline and Paul Rathblatt Suzanne Perrault and David Rago Judith Schaechter Rago Auction Ruth and Rick Snyderman Nicholas Selch Carol Klein and Larry Spitz James Terrani Paul Stark Elissa Topol and Lee Osterman Jeffrey Sugerman -

Conceito De Mínimo Na Arquitetura: Proposta Para a Quinta Do Canavial (Covilhã)

UNIVERSIDADE DA BEIRA INTERIOR Engenharia Conceito de Mínimo na Arquitetura: proposta para a Quinta do Canavial (Covilhã) Ana Catarina Novais Gavina Dissertação para obtenção do Grau de Mestre em Arquitetura (ciclo de estudos integrado) Orientador: Prof. Doutor Ana Maria Tavares Ferreira Martins Co-orientador: Prof. Doutor Miguel Costa santos Nepomoceno Covilhã, Abril de 2016 ii Dedicatória Aos meus pais e irmã. iii iv Agradecimentos A todos aqueles que me acompanharam neste percurso, família, amigos, orientadores mas em especial aos meus pais e irmã que sem eles era impossível chegar até ao fim. v vi Resumo A presente dissertação irá abordar como tema fulcral a Habitação tendo de conceito principal o mínimo nas suas múltiplas vertentes. Desta forma, intrínsecos a esta temática, estão conceitos como o Minimalismo, a Flexibilidade e Funcionalidade. Apesar do Minimalismo ter tido as suas origens nas Artes Plásticas, em meados do séc. XX, já anteriores movimentos arquitétónicos tinham revelado resultados concordantes com os do Minimalismo (enquanto corrente estilística), como poderemos analisar através de exemplos escolhidos a nível do património histórico e do património contemporâneo da cela mínima e da habitação mínima, na Parte I. Respetivamente, o primeiro refere-se às celas monásticas e o segundo é relativo ao habitar mínimo tipicamente japonês, analisando pormenorizadamente os seus componentes e formas de habitar. Conclui-se a Parte I com um estudo da flexibilidade e multifuncionalidade de uma habitação, anunciando a filosofia “a forma segue a função”. Seguidamente, a Parte II, é exclusivamente dedicada à proposta do protótipo da habitação minimalista. Analisa-se primeiramente o terreno em questão, avaliando as suas considerações juntamente com as condicionantes da família do cliente. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Transience and durability in Japanese urban space ROBINSON, WILFRED,IAIN,THOMAS How to cite: ROBINSON, WILFRED,IAIN,THOMAS (2010) Transience and durability in Japanese urban space, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/405/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Iain Robinson Transience and durability in Japanese urban space ABSTRACT The thesis addresses the research question “What is transient and what endures within Japanese urban space” by taking the material constructed form of one Japanese city as a primary text and object of analysis. Chiba-shi is a port and administrative centre in southern Kanto, the largest city in the eastern part of the Tokyo Metropolitan Region and located about forty kilometres from downtown Tokyo. The study privileges the role of process as a theoretical basis for exploring the dynamics of the production and transformation of urban space. -

Introducing Tokyo Page 10 Panorama Views

Introducing Tokyo page 10 Panorama views: Tokyo from above 10 A Wonderful Catastrophe Ulf Meyer 34 The Informational World City Botond Bognar 42 Bunkyo-ku page 50 001 Saint Mary's Cathedral Kenzo Tange 002 Memorial Park for the Tokyo War Dead Takefumi Aida 003 Century Tower Norman Foster 004 Tokyo Dome Nikken Sekkei/Takenaka Corporation 005 Headquarters Building of the University of Tokyo Kenzo Tange 006 Technica House Takenaka Corporation 007 Tokyo Dome Hotel Kenzo Tange Chiyoda-ku page 56 008 DN Tower 21 Kevin Roche/John Dinkebo 009 Grand Prince Hotel Akasaka Kenzo Tange 010 Metro Tour/Edoken Office Building Atsushi Kitagawara 011 Athénée Français Takamasa Yoshizaka 012 National Theatre Hiroyuki Iwamoto 013 Imperial Theatre Yoshiro Taniguchi/Mitsubishi Architectural Office 014 National Showa Memorial Museum/Showa-kan Kiyonori Kikutake 015 Tokyo Marine and Fire Insurance Company Building Kunio Maekawa 016 Wacoal Building Kisho Kurokawa 017 Pacific Century Place Nikken Sekkei 018 National Museum for Modern Art Yoshiro Taniguchi 019 National Diet Library and Annex Kunio Maekawa 020 Mizuho Corporate Bank Building Togo Murano 021 AKS Building Takenaka Corporation 022 Nippon Budokan Mamoru Yamada 023 Nikken Sekkei Tokyo Building Nikken Sekkei 024 Koizumi Building Peter Eisenman/Kojiro Kitayama 025 Supreme Court Shinichi Okada 026 Iidabashi Subway Station Makoto Sei Watanabe 027 Mizuho Bank Head Office Building Yoshinobu Ashihara 028 Tokyo Sankei Building Takenaka Corporation 029 Palace Side Building Nikken Sekkei 030 Nissei Theatre and Administration Building for the Nihon Seimei-Insurance Co. Murano & Mori 031 55 Building, Hosei University Hiroshi Oe 032 Kasumigaseki Building Yamashita Sekkei 033 Mitsui Marine and Fire Insurance Building Nikken Sekkei 034 Tajima Building Michael Graves Bibliografische Informationen digitalisiert durch http://d-nb.info/1010431374 Chuo-ku page 74 035 Louis Vuitton Ginza Namiki Store Jun Aoki 036 Gucci Ginza James Carpenter 037 Daigaku Megane Building Atsushi Kitagawara 038 Yaesu Bookshop Kajima Design 039 The Japan P.E.N. -

Bringing the Vernacular Into Modernism

Scuola Italiana di Studi École Française BY CO-HOSTED sull’Asia Orientale d’Extrême-Orient ISEAS EFEO Friday, December 11th, 18:00h Yola Gloaguen SPEAKER Antonin Raymond’s career allows us to explore the dy- namics and implications of the development of European Bringing and American architectural modernism in a non-Western context. The Czech-born American architect arrived in Japan on the eve of 1920 to assist Frank Lloyd Wright with building the new Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. However, the Vernacular Raymond soon opened his own oce in the capital and became one of the pioneers of modern architecture in Japan. The human and technical challenges taken on by into Modernism Raymond included responding to an increasing demand for the design of villas suited to the Western and Japanese lifestyles of Tokyo’s international elites. This was reected in the spatial design and construction of these new types Architect of houses. The talk will highlight various examples of prewar and postwar residential works, with a focus on how Raymond and his team developed an approach to Antonin Raymond design based on the appropriation and adaptation of selected elements of the Japanese vernacular into the Western modernist idiom, which itself had to be reevalu- in Interwar Japan ated in the particular context of Japan. This approach to Raymond’s work provides a means to reassess the usual binaries of Western inuence and Japanese adaptation through the medium of architecture. Yola Gloaguen is a postdoctoral researcher at the Centre de recherche sur les civilisations de l’Asie orientale–CRCAO, Paris. After receiving her degree in architecture from Paris La Villette School of Architecture, she became a doctoral student at Kyoto University and studied modern architectural history in Japan. -

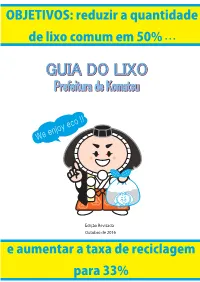

OBJETIVOS: Reduzir a Quantidade De Lixo Comum Em 50% . . . E Aumentar a Taxa De Reciclagem Para

OBJETIVOS: reduzir a quantidade de lixo comum em 50% . Edição Revisada Outubro de 2016 e aumentar a taxa de reciclagem para 33% ÍNDICE Parte 1 Rumo à redução do lixo e aumento da reciclagem 3 O que podemos fazer agora 3 Para reaproveitar os recursos, é necessário separar 3 Drenar a água, secar o lixo, fazer a compostagem 3 O novo sistema dos “Sacos da Dieta do Lixo” 4 Parte 2 Categorias de Lixo e Métodos de Processamento 6 11 Categorias de Lixo e 20 tipos de artigo 6 Lixo Queimável(Lixo Comum) 6 Lixo de Embalagens Plásticas 7 Papéis Recicláveis 9 Latas 10 Metais 10 Lixo a ser Triturado 11 Garrafas de Vidro 11 Lixo Tóxico 12 Garrafas PET 12 Lixo a ser Aterrado 13 Lixo de Grande Porte (77 artigos designados) 14 Roupas e artigos de tecido: locais de coleta 17 Estações de reciclagem 18 Parte 3 Lixo que a Prefeitura não recolhe 19 1. Lixo em grande quantidade ou de grandes dimensões 19 2. Pneus e Baterias 19 3. Descarte de eletrodomésticos regulado por lei 20 4. Computadores 21 5. Veículos de duas rodas 21 6. Extintores de Incêndio 22 7. Botijão de Gás Propano 22 8. Limpeza de Banheiros Químicos 23 Parte 4 Descarte ilegal de lixo e outras questões 24 1. Descarte ilegal de lixo 24 2. Incineração ao ar livre 24 3. Empresas privadas para coleta de lixo comum 25 ◆ Lista de materiais em ordem alfabética: como separar cada item 26 ◆ LIXO QUE NÃO DEVE SER JOGADO NO LOCAL DE COLETA DE SEU BAIRRO NEM LEVADO AO BIKA CENTER RUMO À REDUÇÃO DO LIXO E AUMENTO DA RECICLAGEM “Smart city”: cidade, pessoas e meio ambiente em harmonia ●O que podemos fazer agora O descarte de lixo é uma questão crucial para se pensar o meio ambiente global. -

Press Release for Editing

Moderne Gallery Is Making A Move! - as always...looking forward, taking the lead ---- From Old City to Port Richmond, Philadelphia, in January 2019 Moderne Gallery, recognized internationally as the prime gallery for studio craft furniture, and as the leading Nakashima dealer in the world, is moving to a new center for high end design, art and antiques in the Port Richmond section of Philadelphia, as of January 2019. The new showroom is not open to the public as of yet, but can be visited by appointment only. It is set to open in the Spring of 2019. Moderne Gallery will be the first tenant in the Showrooms at 2220, a newly restored former mill at 2220 East Allegheny Avenue, (Port Richmond) Philadelphia, PA 19134. The 100,000 square-foot building is owned and managed by Jeffrey Kamal and Joe Holahan, co-owners of Kamelot Auction Company, which holds its auctions and has its offices in the building. "We are not downsizing, or giving up our showroom concept with special exhibitions," says Moderne Gallery founder/director Robert Aibel. "And certainly we will continue to build our business through internet sales." Joshua Aibel, Robert's son, is now co-director of Moderne Gallery and helping to develop this combination of sales concepts. "We see this as an opportunity to move to a setting that presents a comprehensive, easily accessible major art, antiques and design center for our region, just off I-95," says Josh Aibel. "The Showrooms at 2220 offer an attractive new venue with great showroom spaces and many advantages for our storage and shipping requirements." Moderne Gallery's new showrooms are being designed by the gallery's longtime interior designer Michael Gruber of Philadelphia. -

Maverick Impossible-James Rose and the Modern American Garden

Maverick Impossible-James Rose and the Modern American Garden. Dean Cardasis, Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture, University of Massachusetts (Amherst) “To see the universe within a place is to see a garden; approach to American garden design. to see it so is to have a garden; Rose was a rugged individualist who explored the not to prevent its happening is to build a garden.” universal through the personal. Both his incisive James Rose, Modern American Gardens. writings and his exquisite gardens evidence the vitality of an approach to garden making (and life) as James Rose was one of the leaders of the modern an adventure within the great cosmic joke. He movement in American garden design. I write this disapproved of preconceiving design or employing advisedly because James “ the-maverick-impossible” any formulaic method, and favored direct Rose would be the first to disclaim it. “I’m no spontaneous improvisation with nature. Unlike fellow missionary,” he often exclaimed, “I do what pleases modern rebels and friends, Dan Kiley and Garrett me!”1 Nevertheless, Rose, through his experimental Eckbo, Rose devoted his life to exploring the private built works, his imaginative creative writing, and his garden as a place of self-discovery. Because of the generally subversive life-style provides perhaps the contemplative nature of his gardens, his work has clearest image of what may be termed a truly modern sometimes been mislabeled Japanesebut nothing made Rose madder than to suggest he did Japanese gardens. In fact, in response to a query from one prospective client as to whether he could do a Japanese garden for her, Rose replied, “Of course, whereabouts in Japan do you live?”2 This kind of response to what he would call his clients’ “mind fixes” was characteristic of James Rose. -

Lisa Gralnick

Lisa Gralnick (608) 262-0189 (office) (608) 262-2049 (studio) E-mail: [email protected] Education 1980 Master of Fine Arts, State University of New York, New Paltz (Gold and Silversmithing) Major Professors: Kurt Matzdorf and Robert Ebendorf 1977 Bachelor of Fine Arts, Kent State University Major Professors: Mary Ann Scherr and James Someroski Teaching Appointments 2007- present Professor of Art, University of Wisconsin-Madison 2004-2007 Associate Professor of Art, University of Wisconsin-Madison 2001-2004 Assistant Professor of Art, University of Wisconsin-Madison 1991-01 Full-Time Faculty, Parsons School of Design, New York, NY (Chair of Metals /Jewelry Design Program) 1982-83 Visiting Assistant Professor, Head of Jewelry Dept., Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, Halifax 1980-81 Visiting Assistant Professor, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio Grants, Awards, Fellowships, and Honors 2012 Faculty Development Grant, University of Wisconsin-Madison 2012 Kellett Mid-Career Award, University of Wisconsin-Madison 2010 Wisconsin Arts Board Individual Artist Fellowship 2010 Graduate School Faculty Research Grant, University of Wisconsin- Madison 2009 Rotasa Foundation Grant to fund exhibition catalog at Bellevue Arts Museum 2009 Graduate School Faculty Research Grant, University of Wisconsin- Madison 2008 Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Oral Interview (available online) 2008 Graduate School Faculty Research Grant, University of Wisconsin- Madison 2007 Graduate School Faculty Research Grant, University of Wisconsin- Madison -

1 Japanese Architecture in Hebrew the Influence of Japanese

Japanese Architecture in Hebrew The influence of Japanese Architecture on Israeli Architecture Arie Kutz Architect and urban planner. Graduated from the Tokyo Institute of Technology. He is currently a lecturer at the East Asian Studies department of Tel Aviv University. [email protected] “The International Style,” so coined for its worldwide quick and deep spread in the post-world war II years, has its origins in the European modernism and the vocabulary further developed by the Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier. Its influence reached Israel and Japan simultaneously during its forming years from the late1920’s to its pick influence after World War II. Architects from both countries were deeply influenced by the "international style," both directly through the European sources, and through their contemporaries. It is important to note that both postwar Japan and Israel after its Independence war (1948) went through decades of very fast building. After the first wave of building, which was preoccupied with residential architecture, there came in both countries a second important wave , of public buildings – city halls, museums, concert halls, and universities. It is important to understand that in the 1960’s, the projects of Le Corbusier ( 1887 – 1965) were the main source of inspiration, not to say – of copying. But his projects, being too few, were not enough, so the attention went to his followers and pupils. Among his direct disciples one can count two prominent Japanese architects: Kunio Maekawa (1905 - 1986) and Junzo Sakakura (1901—1969). Both worked for Le Corbusier in the late 1920’s and early 1930’s, went back to Japan, and played a very central role in the Japanese architectural scene in the postwar years. -

City/Town: Malvern C\~Re C4yffv I^''11^ F> ) Vicinity: State: PA County: Chester Code: 029 Zip Code: 19301

, lpNAL HISTORIC LANDMARK "^INATION ' NPS Form 10-900USDI/NPS NRHP Regiitn^^-- /(Rev. 8-86) .^B OMB No. 1024-0018 WHARTON ESHERICK STUDIO ^ Page 1 United States Department of the Interior. National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: THE WHARTON ESHERICK STUDIO Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 1520 Horseshoe Trail Not for publication: City/Town: Malvern C\~re c4yffV i^''11^ f> ) Vicinity: State: PA County: Chester Code: 029 Zip Code: 19301 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private:_X_ Building(s): X Public-local:__ District:__ Public-State:__ Site:__ Public-Federal:__ Structure: Object:__ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 5 ____ buildings ____ ____ sites ____ 1 structures ____ ____ objects 5 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 5 Name of related multiple property listing: NPS Fonn 10-900USDI/NPS NRHP Rcjiitrato^m" "w. 8-86) ^T V OMB No. 1024-0018 WHARTON ESHERICK S1^D_J A..) Page 2 United Sutei Department of the Interior. NMJoojd Park Service . ^^ Nuional Register of Historic Placet Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this ___ nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Exhibit Catalog (PDF)

Mastery in Jewelry & Metals: Irresistible Offerings! Gail M. Brown, Curator Mastery in Jewelry & Metals: Irresistible Offerings! Gail M. Brown, Curator Participating Artists Julia Barello Mary Lee Hu Harriete Estel Berman Michael Jerry Elizabeth Brim Robin Kranitzky & Kim Overstreet Doug Bucci Rebecca Laskin Kathy Buszkiewicz Keith Lewis Harlan W. Butt Charles Lewton-Brain Chunghi Choo Linda MacNeil Sharon Church John Marshall John Cogswell Bruce Metcalf Chris Darway Eleanor Moty Jack DaSilva Tom Muir Marilyn DaSilva Harold O'Connor Robert Ebendorf Komelia Okim Sandra Enterline Albert Paley Fred Fenster Beverly Penn Arline Fisch Suzan Rezac Pat Flynn Stephen Saracino David C. Freda Hiroko Sato-Pijanowski Don Friedlich Sondra Sherman John G. Garrett Helen Shirk Lisa Gralnick Lin Stanionis Gary S. Griffin Billie Theide Laurie Hall Rachelle Thiewes Susan H. Hamlet Linda Threadgill Douglas Harling What IS Mastery? A singular idea, a function, a symbol becomes a concept, a series, a marker- a recognizable visual attitude and identifiable vocabulary which grows into an observation, a continuum, an unforgettable commentary. Risk taking. Alone and juxtaposed….so many ideas inviting exploration. Contrasting moods and attitudes, stimuli and emotional temperatures. Subtle or bold. Serene or exuberant. Pithy observations of the natural and WHAT is Mastery? manmade worlds. The languages of beauty, aesthetics and art. Observation and commentary. Values and conscience. Excess and dearth, The pursuit and attainment, achievement of purpose, knowledge, appreciation and awareness. Heavy moods and childlike insouciance. sustained accomplishment and excellence. The creation of irrepressible, Wisdom and wit. Humor and critique. Reality and fantasy. Figuration important studio jewelry and significant metal work: unique, expressive, and abstraction.