Wright, Russel, Home, Studio and Forest Garden; Dragon Rock (Residence)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WINTER 2007 • Russel Wright • New Aussie Digs $5.95 $7.95 Can on Sale Until March 1, 2008 TOC 2 16 10/18/07 10:57 AM Page 6

F_AR issue16 cover 10/17/07 5:10 PM Page 1 WINTER 2007 • russel wright • new aussie digs $5.95 $7.95 can On sale until March 1, 2008 TOC 2 16 10/18/07 10:57 AM Page 6 contents features 18 atomic aussie New construction down under channels the ’50s. 34 russel wright: 20th century tastemaker The designer’s daughter on growing up Wright. 48 artists in residence A homemade modernist house in Echo Park. 62 collecting: shirt-pocket transistor radios The great-great granddaddy of the iPod. 72 houston two-step Two Texas households that could not be 18 more different. 34 48 TOC 2 16 10/18/07 10:58 AM Page 7 winter 2007 departments 10 meanwhile ... back at the ranch 12 modern wisdom 30 home page Midcentury ranches in scenic Nebraska, Delaware and Tejas. 82 60 atomic books & back issues 69 postscript Digging up house history 82 cool stuff Goodies to whet your appetite 88 ranch dressing Chairs, daybeds, block resources and more. 94 events Upcoming MCM shows 98 buy ar 99 coming up in atomic ranch 99 where’d you get that? 100 atomic advertisers cover A home in Echo Park, Calif., has been in the 62 same family since it was built in 1950. The master bedroom’s birch paneling was refinished and the worn original asphalt tile replaced with ceramic pavers. The bed is by Modernica and the bedside lamp is a 1980s “Pegasus” by artist Peter Shire, who grew up in the house. His “Oh My Gatto” chair sits near the picture window. -

Lewis Mumford – Sidewalk Critic

SIDEWALK CRITIC SIDEWALK CRITIC LEWIS MUMFORD’S WRITINGS ON NEW YORK EDITED BY Robert Wojtowicz PRINCETON ARCHITECTURAL PRESS • NEW YORK Published by Library of Congress Princeton Architectural Press Cataloging-in-Publication Data 37 East 7th Street Mumford, Lewis, 1895‒1990 New York, New York 10003 Sidewalk critic : Lewis Mumford’s 212.995.9620 writings on New York / Robert Wojtowicz, editor. For a free catalog of books, p. cm. call 1.800.722.6657. A selection of essays from the New Visit our web site at www.papress.com. Yorker, published between 1931 and 1940. ©1998 Princeton Architectural Press Includes bibliographical references All rights reserved and index. Printed and bound in the United States ISBN 1-56898-133-3 (alk. paper) 02 01 00 99 98 5 4 3 2 1 First edition 1. Architecture—New York (State) —New York. 2. Architecture, Modern “The Sky Line” is a trademark of the —20th century—New York (State)— New Yorker. New York. 3. New York (N.Y.)— Buildings, structures, etc. I. Wojtowicz, No part of this book my be used or repro- Robert. II. Title. duced in any manner without written NA735.N5M79 1998 permission from the publisher, except in 720’.9747’1—dc21 98-18843 the context of reviews. CIP Editing and design: Endsheets: Midtown Manhattan, Clare Jacobson 1937‒38. Photo by Alexander Alland. Copy editing and indexing: Frontispiece: Portrait of Lewis Mumford Andrew Rubenfeld by George Platt Lynes. Courtesy Estate of George Platt Lynes. Special thanks to: Eugenia Bell, Jane Photograph of the Museum of Modern Garvie, Caroline Green, Dieter Janssen, Art courtesy of the Museum of Modern Therese Kelly, Mark Lamster, Anne Art, New York. -

Radio City Music Hall, Ground Floor Interior

Landmarks Preservation Commission March 28, 1978, Designation List No.I 14 LP-0995 RADIO CITY MUSIC HALL, ground floor interior consisting of the ticket lobby and ticket booths, advance sales lobby and ticket booth, inner lobby, south entrance vestibule, curved staircase at south end, entrance foyer, grand foyer, grand staircase, exit lobby, elevator lobby and elevator cabs, auditorium, including the seats, side ramps, staircases, I ight control board, orchestra pit, the stage and stage wings; interior of the first level below the ground floor consisting of the main lounge and its staircases, elevator lobby and elevator cabs, men's lounge, men's washroom, men's toilet, foyer, women's lounge, powder room, women's washroom, women's toilet, orchestra pit, stage elevator; first mezzanine interior consisting of the upper part of the grand foyer, grand staircase and landing, lounge, curved staircase at south end, powder room, telephone alcove, women's toilet, smoking room, telephone alcove, men's toilet, promenade, foyer, north staircase connecting first and second mezzanines, elevator lobby and elevator cabs, first balcony including seats, upper part of the auditorium, upper part of the stage house; second mezzanine interior consisting of the upper part of the grand foyer, lounge, curved staircase at south end, powder room, telephone alcove, women's toilet, smoking room, telephone alcove, men's toilet, promenade, foyer, north staircase connecting second and third mezzanines, elevator lobby and elevator cabs, second balcony including seats, -

Design Goals

58 CHAPTER 5 The Objects of the American-Way Program Design Concepts For Russel Wright, the democracy of the machine and the individuality of the craftsman were each elemental to the American character and national wellbeing. As an organizing construct of the American-Way program, the combination of hand- and machine-made products became a prescription for American homes and a merging of production processes. Singly and as a collection, they reflected the blending of professional design with amateur experimentation, rural handcraft with studio art, factory processes and traditional folkways. A notable effect of this multiplicity of intentions in the American-Way products was a duality of nature in some of the products. Machine-made products sometimes looked like they were made by hand, and vice versa. Mary Wright’s designs for Everlast Aluminum, for example, had the hand-made properties of hammered aluminum, although they were a factory production (Figure 8). Likewise, Russel’s Oceana line, which predated the American-Way program but was incorporated into it, was a mass-produced series of wooden accessories carefully designed to look as if they had come from the hand of a woodworker (Figure 31). Conversely, objects considered part of the crafts program, such as Norman Beals’ Lucite bowls, had slick, rigid qualities reminiscent of the machine (Figure 9). Another material cross-fertilization resulted from the way Wright structured the program, asking designers and artists in some cases to contribute designs completely outside their fields of expertise. Thus, architect Michael Hare designed wooden tableware; movie set designer and House Beautiful contributor Joseph Platt did glassware; and painters Julian Levi and John Steuart 59 Curry supplied designs for printed drapery fabrics. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information C om pany 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313 761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9031153 The utilitarian object as appropriate study for art education: An historical and philosophical inquiry grounded in American and British contexts Sproll, Paul Anthony, Ph.D. -

Town of Philipstown Planning Board

Town of Philipstown Planning Board Meeting Agenda Butterfield Library, Cold Spring, New York 10516 July 30, 2015 7:30 PM Public Hearing VISTA44 LLC (dba Garrison Cafe) Pledge of Allegiance Roll Call Approval of Minutes: June 18, 2015 VISTA44 LLC (dba Garrison Cafe) - Application for major site plan - 1135 Route 9D, Garrison, NY: Submission of revised plans/discussion Gex - Lot line change - 24 Hummingbird Lane, Garrison, NY - Request for extension Manitoga - Special Use Permit #188 - 22 Old Manitou Road, Garrison, NY: Update Adjourn Anthony Merante, Chairman Note: All items may not be called. Items may not always be called in order. PhilipstQwn Planning Board Public Hearing - July30, 2015 The Philipstowll Planning Board for the Town of Philipstown, New York will hold a public hearing on Thursday, July 30 at 7:30 p.m. at the Butterfield Library on Morris Avenue in Cold Spring, New York to consider the following application: VISTA44 llC dba Garrison Cafe - Application dated June 4, 2015, for a major site plan approval. The application involves two adjacent parcels along the west side of NYS Route 90, immediately south of Grassi Lane. The northerly parcel is currently developed with two commercial buildings, while the southerly parcel is residentially zoned. The applicants currently operate the Garrison Cafe in a portion of the southerly building on the commercial site. The remainder ofthis building contains.a 3 bedroom apartment, which is currently unoccupied. The applicant seeks approval to expand the cafe to the north into a portion of the apartment where it will operate a wine bar and provide additional and more formal dining facilities. -

Winold Reiss: a Pioneer of Modern American Design

38 Queen City Heritage Winold Reiss: A Pioneer of Modern American Design C. Ford Peatross commercial art, that was a notable characteristic of his time. The professions of commercial and industrial design as we know them today developed out of this stimulating Cincinnati is especially fortunate in having convergence. We are just beginning to study and to recog- not only one of Winold Reiss's most ambitious commis- nize the multiple contributions which Reiss made to sions, but also one of the few that survives, for the nature American architecture and design. He helped to prepare of most of his work in commercial architecture and interi- the way for figures like Raymond Loewy, Norman Bel or design was necessarily ephemeral. As a public building, Geddes, Donald Deskey, and Walter Dorwin Teague, Cincinnati's Union Terminal is also exceptional in Reiss's among others who established the United States as a work, although the many restaurants, hotels, and shops world leader in commercial and industrial design during which he designed were at one time a part of the daily the 1930s. In 1913, however, this country was on the dis- lives of thousands of people. So prolific was Reiss, that by tant edges of the coming wave of change. 1940, not counting the Cincinnati station, in any one day over 30,000 Americans lived, met, ate, drank, or were entertained in a Reiss designed interior. Today Cincinnatians are alone in this privilege. "Masterpieces" of architecture, landscape, and interior design too often lie outside the paths of ordinary people. Historians of vernac- ular and commercial architecture are now directing increasing attention to the transitory structures which con- stitute such an important part of our built environment, and which play significant roles in the quality of our lives. -

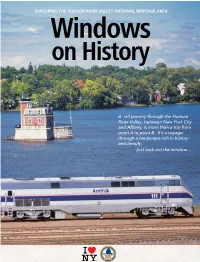

Windows on History

EXPLORING THE HUDSON RIVER VALLEY NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA Windows on History A rail journey through the Hudson River Valley, between New York City and Albany, is more than a trip from point A to point B. It’s a voyage through a landscape rich in history and beauty. Just look out the window… Na lley tion Va al r H e e v r i i t R a g n e o A s r d e u a H Na lley tion Va al r H e e v r i i t R a g n e o A s r d e u a H W ELCOME TO THE HUDSON RIVER VALLEY! RAVELING THROUGH THIS HISTORIC REGION, you will discover the people, places, and events that formed our national identity, and led Congress to designate the Hudson River Valley as a National Heritage Area in 1996. The Hudson River has also been designated one of our country’s Great American Rivers. TAs you journey between New York’s Pennsylvania station and the Albany- Rensselaer station, this guide will interpret the sites and features that you see out your train window, including historic sites that span three centuries of our nation’s history. You will also learn about the communities and cultural resources that are located only a short journey from the various This project was made station stops. possible through a partnership between the We invite you to explore the four million acres Hudson River Valley that make up the Hudson Valley and discover its National Heritage Area rich scenic, historic, cultural, and recreational and I Love NY. -

Section 1: Comprehensive Planning Process

Philipstown Comprehensive Plan 2006 CHAPTER 1 / BACKGROUND Section 1: Comprehensive Planning Process This Comprehensive Plan is the product of a five-year process in which the residents of Philipstown came together to agree upon a common vision for their future, and the Comprehensive Plan Special Board shaped that vision into this action-oriented document. Over the five years, numerous meetings and two public hearings were held, giving residents many opportunities to offer and respond to ideas and suggestions. This Plan is the culmination of a significant effort by many citizens of Philipstown working together to express who we are and what we want for our future. Although a professional planning consultant provided assistance, this Plan was written by the community and for the community. The process began when the Town Board commissioned a "diagnostic" planning study of the Town by planning consultant Joel Russell. That study, completed in October, 2000, reviewed the 1991 Town Master Plan, and recommended that the Town prepare a more citizen-based comprehensive plan which would be concise and readable, "a new planning document that clearly expresses a set of shared goals and principles." The first step in developing this plan was a town-wide forum bringing a cross-section of the community together to define consensus goals and action strategies to accomplish them. This forum, Philipstown 2020, was held over two and a half days in April, 2001. More than two hundred residents participated. "Philipstown 2020: A Synthesis" (see Appendix A) expresses the outcome of this forum, and its goals were the starting point for preparing this Plan. -

Miami Beach Conflict P

N T R 0 D u C T 0 N I The Miami Beach Art Deco District is our nation's most unique quickens, it threatens to alter the very essence of the community-s resort. For over fifty years, it has sustained itself as a retirement social, architectural and cultural fabric unless properly directed. and vacation community, and until recently, it remained nearly The citizens of Miami Beach have recently begun to appreciate unsurpassed in the accommodations, recreation and scenic setting the inherent attributes of their historic Art Deco District. The latent which it offered to hundreds of thousands of visitors each year. potential of the District is being recognized with a conscious and enthusiastic effort to restore economic health and vitality to the area. They recognize that the District will be unable to attract its All of South Florida is currently experiencing intense development potential share of the strong regional tourist market if positive pressuries because of its ideal climate and seaside environment, action is not taken to reverse the trends of physical deterioration and the Art Deco District is no exception. Land values in the and neglect. They also recognize that the architectural richness District are high, especially for oceanfront property, and the and quality of their community make it a very special place. effects of uncontrolled new development have already become apparent in demolition and insensitive new construction. In some The time has arrived for a full-fledged Preservation and Develop areas, new development has been sensitive to the historic integrity ment Plan to focus this new energy in directions which will most of the District. -

Art Deco Tea Sets and Cocktail Sets Making Modernity Accessible

Art DecO Tea SetS and cOcktail SetS Making MOdernity AcceSSible Melanie Keating Submitted under the supervision of Jennifer Marshall to the University Honors Program at the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts, summa cum laude in Art History. 12/11/2013 Abstract: This essay examines American Art Deco tea sets and cocktails sets and their accessibility to a large audience. It covers the origin of Art Deco and describes certain common features by visually analyzing relevant examples. It argues that Art Deco tea sets and cocktail sets blended aspects of modern and traditional design in order to appeal to progressive and conservative consumers. The designers studied include Jean Puiforcat, Norman Bel Geddes, Virginia Hamill, Gene Theobald, Louis W. Rice, Russel Wright, Howard Reichenbach, and Walter von Nessen. 2 Art Deco Tea Sets and Cocktail Sets Making Modernity Accessible Art Deco debuted in the 1920s and continued to be popular in design for several decades. Clean lines, symmetry, and lack of ornamental details all characterize this bold style (see figures 1 and 5 for examples). Geometric forms based on machines, such as circles, rectangles, spheres, and cylinders, are typical elements. When color is used, it is bright and high contrast. Art Deco was a branch of modernism, a cutting-edge art style, and it also celebrated the scientific advances and rise of the machine associated with modernity during the Interwar Period. Art Deco takes its name from the 1925Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes in Paris, where it first appeared. -

Examining the Structure and Policies of the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum with Implications for Best Practice Hyunkyung Lee

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 Examining the Structure and Policies of the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum with Implications for Best Practice HyunKyung Lee Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY THE COLLEGE OF VISUAL ARTS, THEATRE AND DANCE EXAMINING THE STRUCTURE AND POLICIES OF THE COOPER-HEWITT NATIONAL DESIGN MUSEUM WITH IMPLICATIONS FOR BEST PRACTICE By HYUNKYUNG LEE A dissertation submitted to the Department of Art Education in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2007 Copyright © 2007 Hyunkyung Lee All Right Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Hyunkyung Lee defended on May 1, 2007. ____________________________________________ Tom Anderson Professor Directing Dissertation ____________________________________________ Paul Marty Outside Committee Member ____________________________________________ Pat Villeneuve Committee Member ____________________________________________ Dave Gussak Committee Member Approved: _____________________________________________________________________________ Marcia L. Rosal, Chair, Department of Art Education _____________________________________________________________________________ Sally E. McRorie, Dean, The College of Visual Arts, Theatre and Dance The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My gratitude is extended to all who helped to make this study possible. A special thanks goes to my major professor Dr. Tom Anderson, who guided and encouraged me with full generosity. I also would like to thank my committee members, Dr. Paul Marty, Dr. Pat Villeneuve, and Dr. Dave Gussak for their insightful comments. Special thanks are due to the Department chair, Dr. Marcial Rosal for her support.