The Multimodal Construction of Place in English Folk Field Recordings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Folk for Art's Sake: English Folk Music in the Mainstream Milieu

Volume 4 (2009) ISSN 1751-7788 Folk for Art’s Sake: English Folk Music in the Mainstream Milieu Simon Keegan-Phipps University of Sheffield The English folk arts are currently undergoing a considerable resurgence; 1 practices of folk music, dance and drama that explicitly identify themselves as English are the subjects of increasing public interest throughout England. The past five years have seen a manifold increase in the number of professional musical acts that foreground their Englishness; for the first time since the last 'revival period' of the 1950s and 60s, it is easier for folk music agents to secure bookings for these English acts in England than Scottish and Irish (Celtic) bands. Folk festivals in England are experiencing greatly increased popularity, and the profile of the genre has also grown substantially beyond the boundaries of the conventional 'folk scene' contexts: Seth Lakeman received a Mercury Music Awards nomination in 2006 for his album Kitty Jay; Jim Moray supported Will Young’s 2003 UK tour, and his album Sweet England appeared in the Independent’s ‘Cult Classics’ series in 2007; in 2003, the morris side Dogrose Morris appeared on the popular television music show Later with Jools Holland, accompanied by the high-profile fiddler, Eliza Carthy;1 and all-star festival-headliners Bellowhead appeared on the same show in 2006.2 However, the expansion in the profile and presence of English folk music has 2 not been confined to the realms of vernacular, popular culture: On 20 July 2008, BBC Radio 3 hosted the BBC Proms -

Newsletter 59

SQUIRE: BRIAN TASKER 6 ROOPERS, SPELDHURST, TUNBRIDGE WELLS, KENT, TN3 0QL TEL: 01892 862301 E-mail: [email protected] BAGMAN: CHARLIE CORCORAN 70, GREENGATE LANE, BIRSTALL, LEICESTER, LEICS LE4 3DL TEL: 01162 675654 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] TREASURER: STEVE ADAMSON BFB 12, FLOCKTON ROAD, EAST BOWLING, BRADFORD, WEST YORKSHIRE BD4 7RH TEL: 01274 773830 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] The Newsletter No.59 December 2008 The highlights of this Newsletter are: Page Massed Dances and their music 2 Annual Representatives’ Meeting 3 Information about Chris Harris’ “Kemps Jig” 4 ARM Agenda (and advance request for Reports) 6 Joint Morris Organisations: Nottingham Revels 28th March 2009 8 EFDSS News 8 Francis Shergold (1919-2008) A Tribute by Paul Reece 10 Cultural Olympiad 11 2009 Meetings of Morris Ring 11 Treasurer’s ramblings 11 Who’s going to which meeting? 12 Saddleworth Rushcart 2009 12 Jigs Instructional 2009 13 2009 Rapper and Longsword Tournaments 13 Redcar Sword Dancers triumphant again 14 Morris in the Media – Marks for trying? 14 Future Dates 16 Application Forms: Jigs Instructional 19 Morris Ring Meetings 20 Morris Ring Newsletter No 59 December 2008 Page 1 of 20 THE MORRIS RING IS THE NATONAL ASSOCIATION OF MEN’S MORRIS & SWORD DANCE CLUBS Music for Massed Dancing. Following the article in Newsletter No. 58 Harry Winstone, of Kemp's Men, contacted Brian Tasker, Squire of the Morris Ring, and suggested that we need to provide some indication of the tunes to be used. His comment was “50 musicians all playing their own versions. -

Sound Recording in the British Folk Revival: Ideology, Discourse and Practice, 1950–1975

Sound recording in the British folk revival: ideology, discourse and practice, 1950–1975 Matthew Ord Submitted in fulfilment of the degree of PhD International Centre for Music Studies Newcastle University March 2017 Abstract Although recent work in record production studies has advanced scholarly understandings of the contribution of sound recording to musical and social meaning, folk revival scholarship in Britain has yet to benefit from these insights. The revival’s recording practice took in a range of approaches and contexts including radio documentary, commercial studio productions and amateur field recordings. This thesis considers how these practices were mediated by revivalist beliefs and values, how recording was represented in revivalist discourse, and how its semiotic resources were incorporated into multimodal discourses about music, technology and traditional culture. Chapters 1 and 2 consider the role of recording in revivalist constructions of traditional culture and working class communities, contrasting the documentary realism of Topic’s single-mic field recordings with the consciously avant-garde style of the BBC’s Radio Ballads. The remaining three chapters explore how the sound of recorded folk was shaped by a mutually constitutive dialogue with popular music, with recordings constructing traditional performance as an authentic social practice in opposition to an Americanised studio sound equated with commercial/technological mediation. As the discourse of progressive rock elevated recording to an art practice associated with the global counterculture, however, opportunities arose for the incorporation of rock studio techniques in the interpretation of traditional song in the hybrid genre of folk-rock. Changes in studio practice and technical experiments with the semiotics of recorded sound experiments form the subject of the final two chapters. -

Representation Through Music in a Non-Parliamentary Nation

MEDIANZ ! VOL 15, NO 1 ! 2015 DOI: 10.11157/medianz-vol15iss1id8 - ARTICLE - Re-Establishing Britishness / Englishness: Representation Through Music in a non-Parliamentary Nation Robert Burns Abstract The absence of a contemporary English identity distinct from right wing political elements has reinforced negative and apathetic perceptions of English folk culture and tradition among populist media. Negative perceptions such as these have to some extent been countered by the emergence of a post–progressive rock–orientated English folk–protest style that has enabled new folk music fusions to establish themselves in a populist performance medium that attracts a new folk audience. In this way, English politicised folk music has facilitated an English cultural identity that is distinct from negative social and political connotations. A significant contemporary national identity for British folk music in general therefore can be found in contemporary English folk as it is presented in a homogenous mix of popular and world music styles, despite a struggle both for and against European identity as the United Kingdom debates ‘Brexit’, the current term for its possible departure from the EU. My mother was half English and I'm half English too I'm a great big bundle of culture tied up in the red, white and blue (Billy Bragg and the Blokes 2002). When the singer and songwriter, Billy Bragg wrote the above song, England, Half English, a friend asked him whether he was being ironic. He replied ‘Do you know what, I’m not’, a statement which shocked his friends. Bragg is a social commentator, political activist and staunch socialist who is proudly English and an outspoken anti–racist, which his opponents may see as arguably diametrically opposed combination. -

UNIVERSAL MUSIC • Rammstein – Videos 1995 – 2012 (DVD) • The

Rammstein – Videos 1995 – 2012 (DVD) The Rolling Stones – Grrr (Album Vinyl Box) Insane Clown Posse – Insane Clown Posse & Twiztid's American Psycho Tour Documentary (DVD) New Releases From Classics And Jazz Inside!! And more… UNI13-03 “Our assets on-line” UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 Artwork shown may not be final UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: Hollywood Undead – Notes From The Underground Bar Code: Cat. #: B001797702 Price Code: SP Order Due: December 20, 2012 Release Date: January 8, 2013 File: Hip Hop /Rock Genre Code: 34/37 Box Lot: 25 SHORT SELL CYCLE Key Tracks: We Are KEY POINTS: 14 BRAND NEW TRACKS Hollywood Undead have sold over 83,000 albums in Canada HEAVY outdoor, radio and online campaign First single “We Are” video is expected mid December 2013 Tour in the works 2.8 million Facebook friends and 166,000 Twitter followers Also Available American Tragedy (2011) ‐ B001527502 Swan Song (2008) ‐ B001133102 INTERNAL USE Label Name: Territory: Choose Release Type: Choose For additional artist information please contact JP Boucher at 416‐718‐4113 or [email protected]. UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Avenue, Suite 1, Toronto, ON M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718‐4000 Fax: (416) 718‐4218 UNIVERSAL MUSIC CANADA NEW RELEASE Artist/Title: Black Veil Brides / Wretched And Divine: The Story Of Bar Code: The Wild Ones (Regular CD) Cat. #: B001781702 Price Code: SP 02537 22095 Order Due: Dec. 20, 2012 Release Date: Jan. 8, 2013 6 3 File: Rock Genre Code: 37 Box Lot: 25 Short Sell Cycle Key Tracks: Artist/Title: Black Veil Brides / Wretched And Divine: The Story Of Bar Code: The Wild Ones (Deluxe CD/DVD) Cat. -

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of

“Whiskey in the Jar”: History and Transformation of a Classic Irish Song Masters Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Dana DeVlieger, B.A., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2016 Thesis Committee: Graeme M. Boone, Advisor Johanna Devaney Anna Gawboy Copyright by Dana Lauren DeVlieger 2016 Abstract “Whiskey in the Jar” is a traditional Irish song that is performed by musicians from many different musical genres. However, because there are influential recordings of the song performed in different styles, from folk to punk to metal, one begins to wonder what the role of the song’s Irish heritage is and whether or not it retains a sense of Irish identity in different iterations. The current project examines a corpus of 398 recordings of “Whiskey in the Jar” by artists from all over the world. By analyzing acoustic markers of Irishness, for example an Irish accent, as well as markers of other musical traditions, this study aims explores the different ways that the song has been performed and discusses the possible presence of an “Irish feel” on recordings that do not sound overtly Irish. ii Dedication Dedicated to my grandfather, Edward Blake, for instilling in our family a love of Irish music and a pride in our heritage iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Graeme Boone, for showing great and enthusiasm for this project and for offering advice and support throughout the process. I would also like to thank Johanna Devaney and Anna Gawboy for their valuable insight and ideas for future directions and ways to improve. -

14302 76969 1 1>

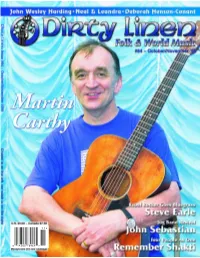

11> 0514302 76969 establishment,” he hastened to clarify. “I wish it were called the Legion of Honour, but it’s not.” Still in all, he thinks it’s good for govern- M artin C arthy ments to give cultural awards and is suitably honored by this one, which has previously gone to such outstanding folk performers as Jeannie Robertson. To decline under such circum- stances, he said, would have been “snotty.” Don’t More importantly, he conceives of his MBE as recognition he shares with the whole Call Me folk scene. “I’ve been put at the front of a very, very long queue of people who work hard to make a folk revival and a folk scene,” he said. Sir! “All those people who organized clubs for nothing and paid you out of their own pocket, and fed you and put you on the train the next morning, and put you to bed when you were drunk! What [the government is] doing, is taking notice of the fact that something’s going on for the last more than 40 years. It’s called the folk revival. They’ve ignored it for that long. And someone has suddenly taken notice, and that’s okay. A bit of profile isn’t gonna hurt us — and I say us, the plural, for the folk scene — isn’t gonna hurt us at all.” In the same year as Carthy’s moment of recognition, something happened that did hurt the folk scene. Lal Waterson, Carthy’s sister-in- law, bandmate, near neighbor and close friend, died of cancer. -

Shirley Collins and the Lodestar Band Live from the Barbican

Shirley Collins and the Lodestar Band Live from the Barbican Start time: 8pm Approximate running time: 60 minutes, no interval Please note all timings are approximate and subject to change. This performance is subject to government guidelines Shirley Collins looks back over her distinguished career as an icon of English folk with Martin Aston , ahead of this special performance to celebrate Heart’s Ease. ‘Time is a bit of a nonsense at the moment,’ ventures Shirley Collins MBE, referring to the stop-start nature of life under COVID-19, before the UK’s third tranche of lockdown ensured that her streamed Live At The Barbican show in February had to be postponed. But as Collins points out, she has experienced worse. In her teens, the country faced the polio outbreak, ‘and you couldn’t go to school or visit anyone,’ she recalls. And there was the small matter of WWII. Collins’ family were evacuated, bombed out of their house, and Shirley and sister Dolly were machine- gunned by a German plane. ‘Mum said, if we saw one to dive under a hedge, so we did,’ she recalls. ‘But the dreadful thing about the pandemic is that you can’t see or feel it coming.’ One wonders if anyone will be writing songs about the pandemic in the same way that people did about the dramas of everyday life in centuries past – love, death, lust, betrayal, pressganging, witchcraft, worker’s rights, murder, and beyond. Even after WWII, Collins’ own life has seen more than its fair share of drama, as detailed in her two memoirs: America Over the Water, about her trip to the American South in 1959 with the song collector Alan Lomax; and the self-explanatory All in the Downs: Reflections on Life, Landscape, and Song, plus one documentary, The Ballad Of Shirley Collins, which told the story of how a young Sussex girl emerged to become the undisputed grand dame of traditional English folk, only to effectively disappear, abandoning recording and performing for 34 years - from 1980 to 2014. -

Topic Records 80Th Anniversary Start Time: 8Pm Running Time: 2 Hours 40 Minutes with Interval

Topic Records 80th Anniversary Start time: 8pm Running time: 2 hours 40 minutes with interval Please note all timings are approximate and subject to change Martin Aston discusses the history behind the world’s oldest independent label ahead of this collaborative performance. When Topic Records made its debut in 1939 with Paddy Ryan’s ‘The Man That Waters The Workers’ Beer’, an accordion-backed diatribe against capitalist businessmen who underpay their employees, it’s unlikely that anyone involved was thinking of the future – certainly not to 2019, when the label celebrates its 80th birthday. In any case, the future would have seemed very precarious in 1939, given the outbreak of World War II, during which Topic ceased most activity (shellac was particularly hard to source). But post-1945, the label made good on its original brief: ‘To use popular music to educate and inform and improve the lot of the working man,’ explains David Suff, the current spearhead of the world’s oldest independent label – and the undisputed home of British folk music. Tonight at the Barbican (where Topic held their 60th birthday concerts), musical director Eliza Carthy – part of the Topic recording family since 1997, though her parents Norma Waterson and Martin Carthy have been members since the sixties and seventies respectively - has marshalled a line-up to reflect the passing decades, which hasn’t been without its problems. ‘We have far too much material, given it’s meant to be a two-hour show!’ she says. ‘It’s impossible to represent 80 years – you’re talking about the left-wing leg, the archival leg, the many different facets of society - not just communists but farmers and factory workers - and the folk scene in the Fifties, the Sixties, the Seventies.. -

Shirley Collins FLED3029 PAGE False True Lovers 02

FLED3029 PAGE False True Lovers 01 Digital Archive Shirley Collins www.thebeesknees.com FLED3029 PAGE False True Lovers 02 Digital Archive Shirley Collins www.thebeesknees.com FLED3029 PAGE False True Lovers 03 Digital Archive Shirley Collins www.thebeesknees.com FLED3029 PAGE False True Lovers 04 Digital Archive Shirley Collins www.thebeesknees.com FLED3029 PAGE False True Lovers 05 In the British-American song tradition folk singers generally reach their prime between But there is more to this matter. A young person, growing up within a folk culture the ages of thirty-five and fifty and often continue to sing extremely well into their acquires this “blás” as he learns his songs. His manner of singing is an integral part seventies. This is a generalisation which applies, with some exceptions of course, to of the whole of each song, and this is precisely what most city singers of folk songs most of the areas I know in North America and Europe. If it is true – and in so vast and lack and can acquire only after years of study and practice. In both the folk and city complex a field as folk-song, generalisation is difficult – the explanation may turn out to environments, however, singers ripen at different ages, depending on their talent and be something like the following. upon their empathy with the material, itself. But I should think it would be comforting On the whole our “big tunes” are of a contemplative, restrained and somewhat for anyone interested in the art of folk-singing to reflect that, all things being equal, he melancholy character. -

A History of Family & Music

A History of Family & Music James “Brasser” Copper (1845 - 1924) by John Copper Born in Rottingdean village 1845, son of John a nearby growing crops, as well as assisting the Head farmworker and his wife Charlotte, James was their Shepherd with his daily tasks. It was hard and second child; the first had died in infancy as did tedious work for a youngster, but at least James four of his siblings. Although clearly from a humble was able to contribute a few shillings each week to background, James was to distinguish himself the family income. amongst his peers by a combination of hard work, determination and a powerful personality. At eighteen he voluntarily attended evening-classes with his brother Thomas (at their own expense) to John had been born on a farmstead outside the learn how to read, write and reckon. Literacy in village in Saltdean valley in 1817. Newlands was the1860s was by no means available to all. It tended tenanted “copyhold” by his father, George Copper to be the preserve of the sons and daughters of the (b.1784). This now defunct form of lease meant that better-off tradespeople and the privileged classes. as long as the tenant kept the ground tilled and in The efforts that the two brothers made towards their good heart the demesne was held rent free, with further education clearly paid off. Thomas, having the landlord retaining timber and mineral rights. first been elevated to Head Carter on the farm went Unfortunately this agreement usually expired on on to become landlord of the principal village pub the tenant’s death, which explains James’s lowly “The Black Horse”, whilst the older brother James birthplace in the little farmworker’s cottage in the worked his way up through the hierarchy of the farm village. -

Download Transcript (131Kb PDF)

Julian Wolfreys, ‘I have only one culture, and it is not mine’: Professions of English Diaspora UCDscholarcast Series 4: (Spring 2010) Reconceiving the British Isles: The Literature of the Archipelago Series Editor: John Brannigan Series Producer: P.J. Mathews © UCDscholarcast 1 Julian Wolfreys, ‘I have only one culture, and it is not mine’: Professions of English Diaspora Julian Wolfreys ‘I have only one culture; and it is not mine’: Professions of English Diaspora? Where I live, on Sunday mornings in spring and early summer I can hear two sounds, one natural, the other technological: sheep, lambs and church bells combine, in rhythmic and arrhythmic canon and counterpoint. It is an aural image, unchanged more or less for several hundred years. It is disrupted only by the interruption of an incoming cut-price flight, making its final descent into East Midlands Airport. However brief the access to the sempiternal is, it remains, nevertheless, as if a moment in time were both opened and suspended, as if I were witness to the voices of a cyclical, communal temporality, voices which have a ground, and which give ground to identity and a sense of being in the same location. In hearing this, my momentary conceit is that I am joined to all those, living and dead, who have heard something similar, and who have therefore been marked by, and have left their otherwise anonymous marks on location. Neither a moment of unbroken continuity nor one of sundered discontinuity, but instead an instant in which, through which, there is the analogical apperception of a ghostly contiguity.