Peripheral Arterial Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FDA Approves ZONTIVITY™ (Vorapaxar), First-In-Class PAR-1

NEWS RELEASE FDA Approves ZONTIVITY™ (vorapaxar), First-in-Class PAR-1 Antagonist, for the Reduction of Thrombotic Cardiovascular Events in Patients with a History of Heart Attack or with Peripheral Arterial Disease 5/12/2014 ZONTIVITY Added to Standard of Care Demonstrated Long-Term Benet Through Three Years Merck (NYSE:MRK), known as MSD outside the United States and Canada, today announced that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved ZONTIVITY™ (vorapaxar) for the reduction of thrombotic cardiovascular events in patients with a history of heart attack (myocardial infarction) or in patients with narrowing of leg arteries, called peripheral arterial disease (PAD). For patients with a history of heart attack or with PAD who had no history of stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA), ZONTIVITY added to standard of care produced a signicant 17 percent relative risk reduction over the three years of the study for the combined events of cardiovascular (CV) death, myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and urgent coronary revascularization (UCR) [event rate 10.1 percent vs. 11.8 percent for placebo]. For the key secondary composite ecacy endpoint of CV death, MI and stroke alone, ZONTIVITY produced a signicant 20 percent relative risk reduction in these patients [7.9 percent vs. 9.5 percent for placebo]. These results were driven by an 18 percent relative risk reduction in MI [5.4 percent vs. 6.4 percent for placebo] and a 33 percent relative risk reduction in rst stroke [1.2 percent vs. 1.6 percent for placebo]. The prescribing information for ZONTIVITY includes a boxed warning regarding bleeding risk. -

Zontivity (Vorapaxar)

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION antiplatelet drugs or with ZONTIVITY as the only antiplatelet These highlights do not include all the information needed to use agent. (2.2) ZONTIVITY safely and effectively. See full prescribing information for ZONTIVITY. --------------------- DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS --------------------- Tablets: 2.08 mg vorapaxar. (3) ZONTIVITY™ (vorapaxar) Tablets 2.08 mg*, for oral use *Equivalent to 2.5 mg vorapaxar sulfate ------------------------------- CONTRAINDICATIONS ------------------------------- Initial U.S. Approval: 2014 History of stroke, TIA, or ICH. (4.1) Active pathologic bleeding. (4.2) WARNING: BLEEDING RISK See full prescribing information for complete boxed warning. ----------------------- WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS ----------------------- • Do not use ZONTIVITY in patients with a history of stroke, Like other antiplatelet agents, ZONTIVITY increases the risk of transient ischemic attack (TIA), or intracranial hemorrhage (ICH); bleeding. (5.1) or active pathological bleeding. (4.1, 4.2) Avoid use with strong CYP3A inhibitors or inducers. (5.2) • Antiplatelet agents, including ZONTIVITY, increase the risk of bleeding, including ICH and fatal bleeding. (5.1) ------------------------------ ADVERSE REACTIONS ------------------------------ Bleeding, including life-threatening and fatal bleeding, is the most ----------------------------INDICATIONS AND USAGE ---------------------------- commonly reported adverse reaction. (6.1) ZONTIVITY is a protease-activated receptor-1 (PAR-1) antagonist indicated for the reduction of thrombotic cardiovascular events in To report SUSPECTED ADVERSE REACTIONS, contact Merck patients with a history of myocardial infarction (MI) or with peripheral Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., at 1-877 arterial disease (PAD). ZONTIVITY has been shown to reduce the rate 888-4231 or FDA at 1-800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch. of a combined endpoint of cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, and urgent coronary revascularization. -

Annexes to the Annual Report of the European Medicines Agency 2014

Annexes to the annual report of the European Medicines Agency 2014 Table of contents Annex 1 – Members of the Management Board ............................................................................. 2 Annex 2 – Members of the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use ................................... 4 Annex 3 – Members of the Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee ...................................... 6 Annex 4 – Members of the Committee for Medicinal Products for Veterinary Use ............................... 8 Annex 5 – Members of the Committee on Orphan Medicinal Products ............................................ 10 Annex 6 – Members of the Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products .............................................. 12 Annex 07 – Committee for Advanced Therapies .......................................................................... 14 Annex 8 – Members of the Paediatric Committee ........................................................................ 16 Annex 9 – Working parties and working groups .......................................................................... 18 Annex 10 – CHMP opinions in 2014 on medicinal products for human use ...................................... 22 Annex 11 – CVMP opinions in 2014 on medicinal products for veterinary use .................................. 36 Annex 12 – COMP opinions in 2014 on designation of orphan medicinal products ............................ 41 Annex 13 – HMPC European Union herbal monographs in 2014.................................................... -

Antithrombotic Therapy in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease and Prior Stroke

Journal of Clinical Medicine Review Antithrombotic Therapy in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease and Prior Stroke Elisa Bellettini and Leonardo De Luca * Department of Cardiosciences, U.O.C. of Cardiology, Azienda Ospedaliera San Camillo-Forlanini, 00152 Roma, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +39-06-58704419; Fax: +39-06-5870-4361 Abstract: Patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) and prior cerebrovascular events (CVE) are frequently faced in clinical practice and present a high rate of both ischemic and bleeding events. For these reasons, the antithrombotic management is particularly challenging in this subgroup of patients. Recent trials suggest that, although a potent antiplatelet strategy is safe in the acute phases of myocardial ischemia for these patients, the risk of major bleeding complications, including intracranial hemorrhage, is extremely high when the antithrombotic therapy is prolonged for a long period of time. Therefore, especially in patients with chronic CAD and history of CVE, the antithrombotic management should be carefully balanced between ischemic and bleeding risks. The present review is aimed at critically evaluating the available evidence to help make these crucial clinical decisions regarding the better antithrombotic therapy to use in this high-risk subgroup Citation: Bellettini, E.; De Luca, L. of patients. Antithrombotic Therapy in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease and Prior Stroke. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, Keywords: antithrombotic therapy; clopidogrel; ticagrelor; prasugrel; aspirin; rivaroxaban; acute 1923. https://doi.org/10.3390/ coronary syndromes; prior stroke jcm10091923 Academic Editors: Wolfgang Dichtl and Andrzej Surdacki 1. Introduction Patients with ischemic stroke present a 4-fold increased risk for coronary artery disease Received: 28 February 2021 (CAD) compared to patients without cerebrovascular diseases (CVD) [1]. -

Patent Application Publication ( 10 ) Pub . No . : US 2019 / 0192440 A1

US 20190192440A1 (19 ) United States (12 ) Patent Application Publication ( 10) Pub . No. : US 2019 /0192440 A1 LI (43 ) Pub . Date : Jun . 27 , 2019 ( 54 ) ORAL DRUG DOSAGE FORM COMPRISING Publication Classification DRUG IN THE FORM OF NANOPARTICLES (51 ) Int . CI. A61K 9 / 20 (2006 .01 ) ( 71 ) Applicant: Triastek , Inc. , Nanjing ( CN ) A61K 9 /00 ( 2006 . 01) A61K 31/ 192 ( 2006 .01 ) (72 ) Inventor : Xiaoling LI , Dublin , CA (US ) A61K 9 / 24 ( 2006 .01 ) ( 52 ) U . S . CI. ( 21 ) Appl. No. : 16 /289 ,499 CPC . .. .. A61K 9 /2031 (2013 . 01 ) ; A61K 9 /0065 ( 22 ) Filed : Feb . 28 , 2019 (2013 .01 ) ; A61K 9 / 209 ( 2013 .01 ) ; A61K 9 /2027 ( 2013 .01 ) ; A61K 31/ 192 ( 2013. 01 ) ; Related U . S . Application Data A61K 9 /2072 ( 2013 .01 ) (63 ) Continuation of application No. 16 /028 ,305 , filed on Jul. 5 , 2018 , now Pat . No . 10 , 258 ,575 , which is a (57 ) ABSTRACT continuation of application No . 15 / 173 ,596 , filed on The present disclosure provides a stable solid pharmaceuti Jun . 3 , 2016 . cal dosage form for oral administration . The dosage form (60 ) Provisional application No . 62 /313 ,092 , filed on Mar. includes a substrate that forms at least one compartment and 24 , 2016 , provisional application No . 62 / 296 , 087 , a drug content loaded into the compartment. The dosage filed on Feb . 17 , 2016 , provisional application No . form is so designed that the active pharmaceutical ingredient 62 / 170, 645 , filed on Jun . 3 , 2015 . of the drug content is released in a controlled manner. Patent Application Publication Jun . 27 , 2019 Sheet 1 of 20 US 2019 /0192440 A1 FIG . -

Cholesterol-Rich Microdomains Contribute to PAR1 Signaling in Platelets Despite a Weak Localization of the Receptor in These Microdomains

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Cholesterol-Rich Microdomains Contribute to PAR1 Signaling in Platelets Despite a Weak Localization of the Receptor in These Microdomains Vahideh Rabani 1, Jennifer Lagoutte-Renosi 1,2 , Jennifer Series 3, Benoit Valot 4, Jean-Marie Xuereb 3 and Siamak Davani 1,2,* 1 EA 3920 Université Bourgogne Franche-Comté, F-25000 Besancon, France; [email protected] (V.R.); [email protected] (J.L.-R.) 2 Laboratoire de Pharmacologie Clinique et Toxicologie-CHU de Besançon, F-25000 Besancon, France 3 Inserm UMR1048, Institut des Maladies Métaboliques et Cardiovasculaires (I2MC), F-31100 Toulouse, France; [email protected] (J.S.); [email protected] (J.-M.X.) 4 UMR CNRS 6249 Chrono-Environnement, Université Bourgogne Franche-Comté, F-25000 Besancon, France; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +33-3-81-66-80-55 Received: 28 September 2020; Accepted: 27 October 2020; Published: 29 October 2020 Abstract: Platelet protease-activated receptor 1 (PAR1) is a cell surface G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) that acts as a thrombin receptor promoting platelet aggregation. Targeting the PAR1 pathway by vorapaxar, a PAR1 antagonist, leads to a reduction in ischemic events in cardiovascular patients with a history of myocardial infarction or with peripheral arterial disease. In platelets, specialized microdomains highly enriched in cholesterol act as modulators of the activity of several GPCRs and play a pivotal role in the signaling pathway. However, their involvement in platelet PAR1 function remains incompletely characterized. In this context, we aimed to investigate whether activation of PAR1 in human platelets requires its localization in the membrane cholesterol-rich microdomains. -

204886Orig1s000

CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: 204886Orig1s000 MEDICAL REVIEW(S) DIVISION OF CARDIOVASCULAR & RENAL PRODUCTS Divisional Memo NDA: 204886 Zontivity; vorapaxar for reduction of atherothrombotic events in patients with a history of myocardial infarction. Sponsor: Merck Review date: 25 April 2014 Reviewer: N. Stockbridge, M.D., Ph.D., HFD-110 Distribution: NDA 204886 This memo conveys the Division’s recommendation to approve this application. This application has been the subject of reviews of CMC (Wong; 9 January 2014), biopharmaceutics (Eradiri; 9 January 2014), pharmacology/toxicology (Harlow; 17 December 2013, 19 February 2014), clinical pharmacology (Hariharan, Bilal, and Li; 16 December 2013), clinical (Rose and Levine; 16 December 2013, 18 April 2014) and statistics (Chen; 13 December 2013). There is a comprehensive CDTL memo (Marciniak; 18 April 2014) with which I am in general agreement. I highlight a few matters here. Vorapaxar is a low molecular weight blocker of PAR-1. On platelets, PAR-1 mediates platelet activation by thrombin, the hexapeptide TRAP, and possibly other short peptides. PAR-1 receptors exist in many other places, although vorapaxar’s effects seem only to be important at the platelet. Although inhibition of PAR-1 is reversible, the half-life of the drug in circulation is longer even than the life of platelets. There are no pending CMC issues. Vorapaxar has 7 chiral centers (b) (4) a single isomer that apparently does not undergo racemization. Crystalline vorapaxar tends to assume an amorphous form upon storage, but these forms are both highly soluble. Manufacturing site inspections are complete. Release specifications have been negotiated. -

Neuraxial Access Or Peripheral Nerve Procedures)

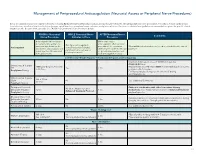

Management of Periprocedural Anticoagulation (Neuraxial Access or Peripheral Nerve Procedures) Below are guidelines to prevent spinal hematoma following Epidural/Intrathecal/Spinal procedures and perineural hematoma following peripheral nerve procedures. Procedures include epidural injec- tions/infusions, intrathecal injections/infusions/pumps, spinal injections, peripheral nerve catheters, and plexus infusions. Decisions to deviate from guideline recommendations given the specific clinical situation are the decision of the provider. See ‘Additional Comments’ section for more details. PRIOR to Neuraxial/ WHILE Neuraxial/Nerve AFTER Neuraxial/Nerve Comments Nerve Procedure Catheter in Place Procedure How long should I hold prior When can I restart to neuraxial procedure? (i.e. anticoagulants after neuraxial Can I give anticoagulants minimum time between the procedures? (i.e. minimum What additional information do I need to consider for the care of Anticoagulant concurrently with neuraxial, last dose of anticoagulant and time between catheter removal patients? peripheral nerve catheter, or spinal injection OR neuraxial/ or spinal/nerve injection and plexus placement? nerve placement) next anticoagulation dose) Low-Molecular Weight Heparin, Unfractionated Heparin, and Fondaparinux Maximum total heparin dose of 10,000 units per day (5000 SQ Q12 hrs) Unfractionated Heparin 5000 units Q 12 hrs – no time Heparin 5000 units SQ 8 hrs is NOT recommended with concurrent SQ Yes 2 hrs restrictions neuraxial catheter in place Prophylaxis Dosing For IV prophylactic dosing, use ‘treatment’ IV dosing recommendations. Unfractionated Heparin SQ: 8-10 hrs SQ/IV No 2 hrs See ‘Additional Comments’ IV: 4 hrs Treatment Dosing Enoxaparin (Lovenox), Caution in combination with other hemostasis-altering No (Note: May be used for Dalteparin (Fragmin) 12 hrs 4 hrs medications. -

Summary of the Risk Management Plan (RMP) for Zontivity (Vorapaxar)

EMA/739006/2014 Summary of the risk management plan (RMP) for Zontivity (vorapaxar) This is a summary of the risk management plan (RMP) for Zontivity, which details the measures to be taken in order to ensure that Zontivity is used as safely as possible. For more information on RMP summaries, see here. This RMP summary should be read in conjunction with the EPAR summary and the product information for Zontivity, which can be found on Zontivity’s EPAR page. Overview of disease epidemiology Zontivity is a medicine used to reduce the occurrence of atherothrombotic events (problems caused by blood clots and hardening of the arteries) such as further heart attacks or strokes in adult patients who have already had a heart attack. The risk of heart attack is greater in people of advanced age, men, people with a family history of heart disease, and in people with high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol levels, diabetes, smoking/tobacco use, alcohol use, obesity, physical inactivity, and/or stress. Despite significant medical advances, patients who have had a heart attack continue to be at risk of a further heart attack or stroke, and have an increased risk of death. Atherothrombotic events remain the leading cause of death worldwide, with approximately 6 in 100 people who experience a heart attack dying within the first year of being discharged from the hospital. Current therapy recommended for patients who have had a heart attack to reduce the risks described above includes aspirin, clopidogrel for those intolerant to aspirin or the combination of aspirin plus clopidogrel; in addition, patients may need medications for treatment of other common conditions (e.g. -

Advances in the Treatment of Stable Coronary Artery Disease and Peripheral Artery Disease

ADVANCES IN THE TREATMENT OF STABLE CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE AND PERIPHERAL ARTERY DISEASE EMCREG-INTERNATIONAL MONOGRAPH PROCEEDINGS FROM THE NOVEMBER 12, 2017 SYMPOSIUM www.emcreg.org ANAHEIM, CA COLLABORATE | INVESTIGATE | EDUCATE COMPLIMENTARY CME MONOGRAPH JANUARY 2018 © Copyright EMCREG-International 2018 ADVANCES IN THE TREATMENT OF STABLE CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE AND PERIPHERAL ARTERY DISEASE EMCREG-International Monograph January 2018 Editor: W. Brian Gibler, MD President, EMCREG-International Professor of Emergency Medicine Department of Emergency Medicine University of Cincinnati College of Medicine Cincinnati, OH Associate Editor: Judy M. Racadio, MD Assistant Editor: Amy L. Hirsch Production & Graphics Design Manager: Todd W. Roat JANUARY 2018 Dear Colleagues, The Emergency Medicine Cardiac Research and Education Group (EMCREG)-International was established in 1989 as an emergency medicine cardiovascular and neurovascular organization led by experts from the United States, Canada, and across the globe. We now have Steering Committee members from the US, Canada, Australia, Belgium, Brazil, France, Netherlands, New Zealand, Japan, Singapore, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Now in our 28th year, we remain committed to providing you with the best educational programs and enduring material pieces possible. In addition to our usual Emergency Physician audience, we now reach out to our colleagues in Cardiology, Internal Medicine, Family Medicine, Hospital Medicine, and Emergency Medicine with our EMCREG-International University of Cincinnati Office of CME accredited symposia and enduring materials. In this EMCREG-International Monograph, Advances in the Treatment of Stable Coronary Artery Disease and Peripheral Artery Disease, you will find a detailed discussion regarding the treatment of these two critically important disease entities. This is a Proceedings Monograph based on the 2017 EMCREG-International Satellite Symposium which was held on November 12, 2017, in Anaheim during the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions. -

Protocol for Non-Interventional Studies Based on Existing Data TITLE PAGE Document Number: C30445781-01

ABCD Protocol for non-interventional studies based on existing data TITLE PAGE Document Number: c30445781-01 BI Study Number: 1237-0090 BI Investigational Stiolto® Respimat® Product(s): The Role of Inhaler Device in the Treatment Persistence with Dual Title: Bronchodilators in Patients with COPD Protocol version 1.0 identifier: Date of last version of N/A protocol: PASS: No EU PAS register Study not registered number: Olodaterol and Tiotropium Bromide (ATC R03AL06) Active substance: Umeclidinium and Vilanterol (ATC R03AL03) Medicinal product: Stiolto® Respimat®; Anoro® Ellipta® Product reference: N/A Procedure number: N/A Joint PASS: No The primary objective of the study is to use US data to determine relative persistence between Olodaterol/Tiotropium Bromide delivered with the Respimat soft mist inhaler and Umeclidinium/Vilanterol delivered with the Ellipta dry powder inhaler using a 1:2 propensity score matched analysis. The secondary objectives of the study are as follows: Research question and - Characterize new users of Olodaterol/Tiotropium Bromide objectives: and Umeclidinium/Vilanterol in terms of demographics, medication use, comorbidities, and other variables, before and after propensity score matching. - Determine the incidence rate and proportion of patients discontinuing or switching among new users of Olodaterol/Tiotropium Bromide and Umeclidinium/ Vilanterol. - Determine the relative rate and proportion of patients discontinuing between Olodaterol/ Tiotropium Bromide and 001-MCG-102_RD-02 (1.0) / Saved on: 22 Oct 2015 Boehringer Ingelheim Page 2 of 69 Protocol for non-interventional studies based on existing data BI Study Number 1237-0090 c30445781-01 Proprietary confidential information © 2019 Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH or one or more of its affiliated companies Umeclidinium/Vilanterol. -

Rivaroxaban Effects Illustrate the Underestimated Importance Of

Journal of Clinical Medicine Article Rivaroxaban Effects Illustrate the Underestimated Importance of Activated Platelets in Thrombin Generation Assessed by Calibrated Automated Thrombography Stephanie Makhoul 1, Marina Panova-Noeva 1,2,Véronique Regnault 3,4 , Wolfram Ruf 1,2,5, Philip Wenzel 1,2,6 and Jeremy Lagrange 1,3,* 1 Center for Thrombosis and Hemostasis, University Medical Center Mainz, 55131 Mainz, Germany; [email protected] (S.M.); [email protected] (M.P.-N.); [email protected] (W.R.); [email protected] (P.W.) 2 DZHK (German Center for Cadiovascular Research), Partner Site Rhine Main, University Medical Center Mainz, 55131 Mainz, Germany 3 Université de Lorraine, INSERM U1116, DCAC, 54505 Nancy, France; [email protected] 4 CHRU Nancy, Vandœuvre-lès-Nancy, 54511 Nancy, France 5 Department of Immunology and Microbial Science, The Scripps Research institute, La Jolla, CA 92037, USA 6 Center for Cardiology—Cardiology I, University Medical Center Mainz, 55131 Mainz, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 19 September 2019; Accepted: 12 November 2019; Published: 15 November 2019 Abstract: Background: The direct oral anticoagulant rivaroxaban inhibiting specifically activated factor X (FXa) causes delayed thrombin generation (TG) as measured by calibrated automated thrombography (CAT). The implications of these changes for assessing bleeding or residual prothrombotic risks of patients are unclear in the absence of a better understanding of the underlying mechanism. Methods: We compared platelet rich plasma (PRP) without or with prior collagen-induced platelet aggregation (agPRP) in the CAT assay to better characterize TG in the presence of rivaroxaban. Results: In the presence of rivaroxaban, TG curves in agPRP showed a distinct profile with a rapidly ascending phase followed with a protracted phase.