A Study of B/M Consonant Variations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phonological Domains Within Blackfoot Towards a Family-Wide Comparison

Phonological domains within Blackfoot Towards a family-wide comparison Natalie Weber 52nd algonquian conference yale university October 23, 2020 Outline 1. Background 2. Two phonological domains in Blackfoot verbs 3. Preverbs are not a separate phonological domain 4. Parametric variation 2 / 59 Background 3 / 59 Consonant inventory Labial Coronal Dorsal Glottal Stops p pː t tː k kː ʔ <’> Assibilants ts tːs ks Pre-assibilants ˢt ˢtː Fricatives s sː x <h> Nasals m mː n nː Glides w j <y> (w) Long consonants written with doubled letters. (Derrick and Weber n.d.; Weber 2020) 4 / 59 Predictable mid vowels? (Frantz 2017) Many [ɛː] and [ɔː] arise from coalescence across boundaries ◦ /a+i/ ! [ɛː] ◦ /a+o/ ! [ɔː] Vowel inventory front central back high i iː o oː mid ɛː <ai> ɔː <ao> low a aː (Derrick and Weber n.d.; Weber 2020) 5 / 59 Vowel inventory front central back high i iː o oː mid ɛː <ai> ɔː <ao> low a aː Predictable mid vowels? (Frantz 2017) Many [ɛː] and [ɔː] arise from coalescence across boundaries ◦ /a+i/ ! [ɛː] ◦ ! /a+o/ [ɔː] (Derrick and Weber n.d.; Weber 2020) 5 / 59 Contrastive mid vowels Some [ɛː] and [ɔː] are morpheme-internal, in overlapping environments with other long vowels JɔːníːtK JaːníːtK aoníít aaníít [ao–n/i–i]–t–Ø [aan–ii]–t–Ø [hole–by.needle/ti–ti1]–2sg.imp–imp [say–ai]–2sg.imp–imp ‘pierce it!’ ‘say (s.t.)!’ (Weber 2020) 6 / 59 Syntax within the stem Intransitive (bi-morphemic) vs. syntactically transitive (trimorphemic). Transitive V is object agreement (Quinn 2006; Rhodes 1994) p [ root –v0 –V0 ] Stem type Gloss ikinn –ssi AI ‘he is warm’ ikinn –ii II ‘it is warm’ itap –ip/i –thm TA ‘take him there’ itap –ip/ht –oo TI ‘take it there’ itap –ip/ht –aki AI(+O) ‘take (s.t.) there’ (Déchaine and Weber 2015, 2018; Weber 2020) 7 / 59 Syntax within the verbal complex Template p [ person–(preverb)*– [ –(med)–v–V ] –I0–C0 ] CP vP root vP CP ◦ Minimal verbal complex: stem plus suffixes (I0,C0). -

July-Aug 2011

St Martin-By-Looe News Published and funded by St Martin-By-Looe Parish Council www.stmartinbylooepc.btck.co.uk July/Aug 2011 Parish Council Update Your Parish Magazine This is the last edition of the Parish Magazine in its current format, the magazine will be relaunched in September as a quarterly publication based around the seasons, Spring, Sum- mer, Autumn and Winter. The content will still be as local as is possible to achieve, however, with your help it could be even better. Please let me know of anything you want to include, this could be a special birthday, anniversary or a special achieve- ment gained at school, college or in the workplace. I am also looking for good quality photographs of the Parish for use in the new look magazine. I can be contacted on 01579 340905 or by email: [email protected] Planning Applications Applications were considered for the removal of Condition 1 and the variation of S106 agreement at Millendreath Holiday Village. The replacement of mobile toilet block with permanent ablution facility at Penhale. Demolition of existing agricultural dwelling and construction of a replacement agricultural dwelling with detached garage at Pethick Farm. Proposed siting of 5 static holiday caravans on land previously used as storage area at Polborder Farm. Donations A £100 donation was agreed for St Martin’s Village Hall Trust for the installation of a disabled door. Meeting Dates You are always welcome to attend the Parish Council Meetings. The next meetings will take place on July 7th and August 25th (September meeting) at 7.30pm. -

The Role of Morphology in Generative Phonology, Autosegmental Phonology and Prosodic Morphology

Chapter 20: The role of morphology in Generative Phonology, Autosegmental Phonology and Prosodic Morphology 1 Introduction The role of morphology in the rule-based phonology of the 1970’s and 1980’s, from classic GENERATIVE PHONOLOGY (Chomsky and Halle 1968) through AUTOSEGMENTAL PHONOLOGY (e.g., Goldsmith 1976) and PROSODIC MORPHOLOGY (e.g., McCarthy & Prince 1999, Steriade 1988), is that it produces the inputs on which phonology operates. Classic Generative, Autosegmental, and Prosodic Morphology approaches to phonology differ in the nature of the phonological rules and representations they posit, but converge in one key assumption: all implicitly or explicitly assume an item-based morphological approach to word formation, in which root and affix morphemes exist as lexical entries with underlying phonological representations. The morphological component of grammar selects the morphemes whose underlying phonological representations constitute the inputs on which phonological rules operate. On this view of morphology, the phonologist is assigned the task of identifying a set of general rules for a given language that operate correctly on the inputs provided by the morphology of that language to produce grammatical outputs. This assignment is challenging for a variety of reasons, sketched below; as a group, these reasons helped prompt the evolution from classic Generative Phonology to its Autosegmental and Prosodic descendants, and have since led to even more dramatic modifications in the way that morphology and phonology interact (see Chapter XXX). First, not all phonological rules apply uniformly across all morphological contexts. For example, Turkish palatal vowel harmony requires suffix vowels to agree with the preceding stem vowels (paşa ‘pasha’, paşa-lar ‘pasha-PL’; meze ‘appetizer’, meze-ler ‘appetizer-PL’) but does not apply within roots (elma ‘apple’, anne ‘mother’). -

Assibilation Or Analogy?: Reconsideration of Korean Noun Stem-Endings*

Assibilation or analogy?: Reconsideration of Korean noun stem-endings* Ponghyung Lee (Daejeon University) This paper discusses two approaches to the nominal stem-endings in Korean inflection including loanwords: one is the assibilation approach, represented by H. Kim (2001) and the other is the analogy approach, represented by Albright (2002 et sequel) and Y. Kang (2003b). I contend that the assibilation approach is deficient in handling its underapplication to the non-nominal categories such as verb. More specifically, the assibilation approach is unable to clearly explain why spirantization (s-assibilation) applies neither to derivative nouns nor to non-nominal items in its entirety. By contrast, the analogy approach is able to overcome difficulties involved with the assibilation position. What is crucial to the analogy approach is that the nominal bases end with t rather than s. Evidence of t-ending bases is garnered from the base selection criteria, disparities between t-ending and s-ending inputs in loanwords. Unconventionally, I dare to contend that normative rules via orthography intervene as part of paradigm extension, alongside semantic conditioning and token/type frequency. Keywords: inflection, assibilation, analogy, base, affrication, spirantization, paradigm extension, orthography, token/type frequency 1. Introduction When it comes to Korean nominal inflection, two observations have captivated our attention. First, multiple-paradigms arise, as explored in previous literature (K. Ko 1989, Kenstowicz 1996, Y. Kang 2003b, Albright 2008 and many others).1 (1) Multiple-paradigms of /pʰatʰ/ ‘red bean’ unmarked nom2 acc dat/loc a. pʰat pʰaʧʰ-i pʰatʰ-ɨl pʰatʰ-e b. pʰat pʰaʧʰ-i pʰaʧʰ-ɨl pʰatʰ-e c. -

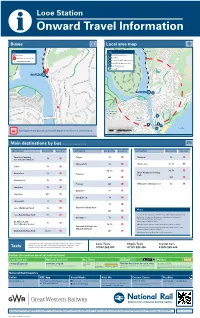

Looe Station I Onward Travel Information Buses Local Area Map

Looe Station i Onward Travel Information Buses Local area map Key Key To Liskeard A Bus Stop i Tourist Information Centre Rail replacement Bus Stop BT Boat Trips LS Local Shops, Pubs & Restaurants Station Entrance/Exit M Old Guildhall, Museum & Gaol PH Pub - The Globe Inn 10 Footpaths m in B A u te s w a Looe Station lk in g d i s t a n c e Looe Station PH C East To Polperro Looe and Pelynt LS West i Looe LS LS M km BT Looe Bay 0 0.5 Rail replacement buses/coaches will depart from the front of the station 0 Miles 0.25 Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2018 & also map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, CC BY-SA Main destinations by bus (Data correct at September 2019) DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP DESTINATION BUS ROUTES BUS STOP Caradon Camping Pelynt 73 A Tideford 72 B 73 A (for Trelawne Manor) Plymouth X 72 B West Looe 72, 73 A Duloe 73 B 72, 73 A 72, 73 A West Waylands Holiday Hannafore 72 A Polperro Park 481 C 481 C Hessenford 72 B Polruan 481 C Widegates (Shortacross) 72 B Landrake 72 B Saltash X 72 B Lansallos 481 C Sandplace ^ 73 B Liskeard ^ 73 B 73 A Looe (Barbican Road) 72 B Seaview Holiday Park Notes 481 C Looe Bay Holiday Park 72 B Bus route 481 operates a limited service Mondays to Fridays only St Keyne [ 73 B Bus route 72 operates Mondays to Saturdays only towards Plymouth, daily towards Polperro No Man's Land Bus route 73 operates daily 72 B (for Polborder House) 72, 73 A ^ Direct trains operate to this destination from this station. -

St Mellion PC Meeting 120116 Minutes DRAFT Iii.Pages

St Mellion Parish Council Meeting Tuesday 12th January 2016 at 7pm in the Church Hall, St Mellion Minutes In attendance: Cllr Ken Henley (KH), Chair; Cllr Steve Crook (SC); Cllr Anita Brocklesby (AB); Cllr Geoffrey Postles (GP); Christine Douglas (CD), Clerk to the Parish Council. Two members of the public. 1. Councillor matters 1.1 To receive apologies for absences Cllr Jean Dransfield (JD) on holiday; Cllr Ian Waite (IW) recovering from surgery. 1.2 To receive declarations of pecuniary interests None. 1.3 To receive declarations of non-registrable interests SC declared an interest in item 7.1 because his well-being may be affected by implementation of street lights on the A388. 1.4 To approve written requests for dispensations None. 2. Previous Parish Council meeting (8th December 2015) 2.1 To approve the minutes It was proposed by GP, seconded by AB and RESOLVED That the pre-circulated minutes were a true reflection of the meeting held on 8.12.15. KH signed and dated the minutes. 2.2 To note matters arising from the minutes None. 3. Police report Saltash neighbourhood policing team Newsletter (Jan 2016): one theft and one public order offence in St Mellion in December. 4. Unitary Councillor’s report Not present. 5. Residents’ Associations’ reports 5.1 St Mellion Village Tenants and Residents (VTRA) Not present. 5.2 St Mellion Park Residents Not present. 6. Questions from the public Paul Hoult reported cars parking by the tennis courts because the yellow lines have worn away, and asked when a light will be installed on the path between The Glebe and the A388. -

4 Polborder Farm Barns Polborder St Mellion ST MELLIONPL12 6RE

4 Polborder Farm Barns Polborder St Mellion ST MELLIONPL12 6RE A self contained first floor appartment in a beautifully converted farm barn. Rural situation surrounded by lovely open countryside. Convenient for St Mellion International Golf And Country Club and within easy commuting distance of Plymouth. Easy access to Saltash and Callington. EPC = C Rent also includes charges for your water This lovely apartment is situated on the first floor of a converted barn in the small hamlet of Polborder which is situated mid way between Callington and Saltash. The apartment has been stylishly converted. Outside there is a communal garden and an allocated parking space. Price: Monthly Rental Of £400 Tel: 01752 850440 www.henningsmoir.com 4 Polborder Farm Barns Polborder St Mellion ST MELLION PL12 6RE DESCRIPTION The property is in a converted barn of other properties that the owners also reside in. Available part furnished as a longer let for a single professional only please. Not suitable for children or pets Water charges included within the rent ENTRANCE HALLWAY Carpeted area, door to flat KITCHEN 6' 01'' x 7' 2'' (1.85m x 2.18m) Small kitchen but with enough cupboard space with worktops over. Electric cooker ( New Feb 2013) Under counter fridge Carpeted Looks out onto garden and countryside LOUNGE 15' 11'' x 11' 5'' (4.85m x 3.48m) Good sized room with feature stone wall. carpeted, neutrally decorated. Electric storage heater. Small cupboard with washing machine plumbed in. Window which looks out onto garden. Stairs to first floor BATHROOM 6' 6'' x 5' 9'' (1.98m x 1.75m) Fitted with Modern white suite of bath , wc and wash hand basin. -

By - Looe Parish Council Friday 8Th January 2021

St Martin – By - Looe Parish Council Friday 8th January 2021. To All Members of the Parish Council. THE PARISH COUNCIL MEETING will be held by ZOOM and telephone on Thursday 14th January 2021 at 7.30pm. The Parish Council Meeting. Public Question Time. IMPORTANT PLEASE READ NOTE BELOW. Agenda Item 1: Declarations of Interest. Agenda Item 2: Apologies for absence. Agenda Item 3: Minutes of the Parish Council/ Planning Zoom Meetings of the 3rd and 10th December 2020. Agenda Item 4: Planning Applications: 4.1.1: Application PA20/09136 Proposal Retention of facility block. Location Penvith Barns Road from Junction South Of Polborder To The Lodge St Martin PL13 1NZ Applicant Andrew Nicholson Grid Ref 228333 / 55071 Agenda Item 5: Planning Decisions received by the date of the meeting. Agenda Item 6: Planning Matters. Notice of Appeal. 6.1.1: Application PA20/08264 Proposal: The change of use of 560 m2 of the site (including 300 m2 of hardstanding) to mixed use agriculture, forestry, temporary tourist accommodation (four glamping pitches) and ancillary facilities. Regularising the siting of: one camping pod (10.8 m2), a composting toilet (1.6 m2), a shower (3.3 m2). Proposed siting of: two camping pods (10.8 m2), a shepherd's hut (10.8 m2), a composting toilet (1.6 m2), a shower (3.3 m2). Proposed engineering works: extended hardstanding (85 m2 additional to existing), adjustment of 9m length of hedge bank at entrance to facilitate visibility, the levelling of land under the pods. Location: Fielda at Bokenver, St Martin by Looe, Cornwall Applicant: Mr Pete Buttery Cornwall Council’s Decision: Failed to determine (The application was not determined within the statutory time period by the Local Planning Authority. -

Palatals in Spanish and French: an Analysis Rachael Gray

Florida State University Libraries Honors Theses The Division of Undergraduate Studies 2012 Palatals in Spanish and French: An Analysis Rachael Gray Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] Abstract (Palatal, Spanish, French) This thesis deals with palatals from Latin into Spanish and French. Specifically, it focuses on the diachronic history of each language with a focus on palatals. I also look at studies that have been conducted concerning palatals, and present a synchronic analysis of palatals in modern day Spanish and French. The final section of this paper focuses on my research design in second language acquisition of palatals for native French speakers learning Spanish. 2 THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES PALATALS IN SPANISH AND FRENCH: AN ANALYSIS BY: RACHAEL GRAY A Thesis submitted to the Department of Modern Languages in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with Honors in the Major Degree Awarded: 3 Spring, 2012 The members of the Defense Committee approve the thesis of Rachael Gray defended on March 21, 2012 _____________________________________ Professor Carolina Gonzaléz Thesis Director _______________________________________ Professor Gretchen Sunderman Committee Member _______________________________________ Professor Eric Coleman Outside Committee Member 4 Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... 5 0. -

Chapter XIII: After the French Invasion

Chapter XIII: After the French Invasion • Introduction • 1066 Battle of Hastings (William the Conqueror) • The Norman Invasion established French as the language of England. • The Normans were originally Vikings (Norman= North + Man) • William established himself as King William I. • Redistributed the lands among his supporters. Ling 110 Chapter XIII: After the 1 French Partition Introduction • Consequently, Norman French became the prestige language in England (government, justice, & education). • English was spoken by only second class citizens. • This social situation had significant consequences for the English language- penetrated the lexicon and the grammar. • English lost the inflectional morphology characteristic of the Germanic languages. • The word order of English came to resemble French word order more than Germanic. Ling 110 Chapter XIII: After the 2 French Partition Introduction con’t • Social stratification can be observed when comparing native words and French borrowings from the same semantic domain. Example: • English French • pig pork • chicken poultry • cow beef • sheep mutton • calf veal The animal is English; the food is French. Illustrating who was tending the animals and who was eating them. Ling 110 Chapter XIII: After the 3 French Partition Introduction con’t • English has borrowed continuously from Latin. • Beginning in the Middle English period, from French. • This pattern of borrowing establishes the opportunity for English to borrow the same word at different points in its history. • Example: English borrowed humility from Latin. The word developed in French and was borrowed again into English as humble. • Two changes have occurred: – The i of humil has been deleted. – A b has been inserted between m and l. -

Assibilation in Trans-New Guinea Languages of the Bird's Head Region

Assibilation in Trans-New Guinea languages of the Bird’s Head region Fanny Cottet Department of Linguistics College of Asia and the Pacific The Australian National University [email protected] Before enlarging the scope to other TNG languages of the Abstract region, the phonological and acoustic properties of Mbahám Previous studies have shown that assibilation of voiced stops assibilation are presented. Mbahám has been tentatively is less common than assibilation of voiceless stops, the former classified as a TNG language of the Bomberai sub-branch. Iha requiring complex and competing aerodynamic conditions to is the only language to which Mbahám is directly related; be produced. The present study reveals that voiced assibilation extended relations to other TNG languages are still under is found synchronically in various Trans-New Guinea investigation. The author is currently working on the phonetic languages of the Bird’s Head region, with the Mbahám and phonological description on the northern variety of the peculiarity that assibilation affects prenasalized voiced stops, a language spoken in the Kokas area (app. 200 speakers). case which has not been described previously. This paper reports new empirical data from previous understudied 2. Mbahám assibilation languages and provides evidences for a new treatment of the phonological inventory of these languages. 2.1. Phonological description In Mbahám, /t/ and /ⁿd/ assibilate before a sequence of two Index Terms: assibilation, Papuan languages, phonology, vocoids whose first segment is [+high]. Examples are given in phonetics, reconstruction. table 1. The triggering segment is realized either in a stressed or an unstressed syllable. In the latter case, the vocoid does not 1. -

Asymmetries and Generalizations in the Repair of Early French Minimally-Rising Syllable-Contact Clusters Francisco Antonio Montaño, Lehman College (CUNY)

Asymmetries and generalizations in the repair of early French minimally-rising syllable-contact clusters Francisco Antonio Montaño, Lehman College (CUNY) The Gallo-Romance (GR) (5th-10th c.) reflexes of Late Latin syncope (Pope 1952; Dumas 1993; Hartkemeyer 2000) provide a unique perspective into the interaction of sonority and phonotactic markedness constraints with faithfulness constraints within the phonology. With the deletion of a pre-tonic or post-tonic short vowel in GR syncopated forms, the preservation, modification, and loss of stranded consonants and neighboring segments occurring in unique clustering permutations reveal a range of repairs on resulting syllable-contact clusters (SCCs). While falling-sonority (manica > manche 'sleeve') and sufficiently-rising obstruent-liquid clusters (tabula > table 'table') unsurprisingly resyllabify without issue into either licit hetero- (SCC) or tautosyllabic (onset) clusters, preserving all consonantal material in the syncopated output, minimally-rising clusters whose final segment is a sonorant undergo diverse repairs to escape eventual total loss, attested only for SCCs containing obstruent codas via gemination then degemination, in avoidance of obstruent-obstruent SCCs (radi[ts]ina > ra[ts]ine 'root', debita > dette > dete 'debt'). Minimally-rising clusters (obstruent-nasal, sibilant-liquid, nasal-liquid), unharmonic both as heterosyllabic clusters due to rising sonority and as onset clusters due to an excessively shallow rise in sonority, undergo a range of phonological repairs including assibilation (platanu > pla[ð]ne > plasne 'plane tree'), rhotacization (ordine > ordre 'order'), and stop epenthesis (cisera > cisdre 'cider'; cumulum > comble 'peak'; camera > chambre 'room'; molere > moldre 'grind.INF' but cf. /rl/ without epenthesis, e.g. merula > merle 'blackbird', evidencing its falling sonority), in order to conform to licensing requirements within the syllable and phonological word (Montaño 2017).