A Film by Nadav Lapid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jewishcommunitynews

Jewish Community News www.jfedps.org The Publication of the Jewish Federation of the Desert Tammuz/Av 5779 - August 2019 Federation Institutes PJ Library Grandparents Initiative Attention Bubbes, Zaydes, Savtas and Sabas! PJ Library, the program that sends free, award-winning books that celebrate Jewish values and culture to families with children six months through 8 years old (plus PJ Our Way for children 9-11, who choose their own free books), is now offering a free program for grandparents of children enrolled in the program. Mary Levine and grandson Teddy Phyllis Pepper and great-grandson Asher To enroll you must have a grandchild with an active PJ Library subscription. Carol Luber and granddaughter Remy Hashanah, Yom Kippur, Sukkot and PJ Library is made possible by the Upon verification, grandparents PJ Library programming locally and Simchat Torah. PJ Library Alliance, Jewish Federations will receive two PJ Library books wherever their grandchildren live. To enroll, go online to pjlibrary. throughout North America including in the mail, monthly emails with Here in the Coachella Valley, PJ org/enrollGP. (For families with our Jewish Federation of the Desert, recipes and activities, updates on Library programs are coordinated young children who are not yet part thousands of generous supporters books and activities being sent to by Federation staff member Leslie of PJ Library: become part of this and the Harold Grinspoon their grandchildren, and PJ Library’s Pepper ([email protected]). wonderful program by going to their Foundation. PROOF magazine. There will also Activities in September/October will website: pjlibrary.org and enroll your be opportunities to contact with focus on the upcoming holidays: Rosh child[ren] now). -

LOC64 Programmino.Pdf

ProgramminoCopertinaFronte_stampa.pdf 1 21.07.11 18.55 ProgramminoCopertinaRetro_stampa.pdf 1 21.07.11 18.48 Il Festival del film Locarno si articola in The Festival del film Locarno comprises una dozzina di sezioni, aperte a tutti i generi a dozen different sections, open to all genres Sezioni 2011 Sections 2011 Piazza Grande: un ricco cartellone di prime Piazza Grande: open-air night screenings mondiali, internazionali o svizzere in un with rich menu of world, international or suggestivo cinema all’aperto che può Swiss premieres, in a splendid setting which accogliere sino a 8 mila spettatori. can accomodate up to 8,000 people. Concorso internazionale: lungometraggi Concorso internazionale (International di fiction o documentari. Competition): fiction and documentary features (fiction and documentaries). Concorso Cineasti del presente: opere prime e seconde di lungometraggi di fiction Concorso Cineasti del presente (Filmmakers o documentari. of the Present Competition): devoted to first and second features. Pardi di domani: un concorso internazionale e uno nazionale di cortometraggi, arricchiti Pardi di domani (Leopards of Tomorrow): da vari programmi speciali. two short films competitions (Concorso Internazionale e Concorso Nazionale), more Fuori concorso: mediometraggi, of various special programs. documentari, opere collettive e i film più recenti di grandi registi. Fuori concorso (Out of competition): screenings of medium-length films, Premi speciali: film dedicati a maestri documentaries, collective works and the del cinema. latest films by major directors. Programmi speciali: comprendono diversi films omaggi, i film dei membri delle giurie e Premi speciali (Special prizes): dedicated to masters of cinema. Cinema svizzero riscoperto. Programmi speciali (Special programs): Retrospettiva Vincente Minnelli: dedicata tributes, jury members’ films and Cinema al maestro della commedia musicale e del svizzero riscoperto (Swiss Cinema melodramma Hollywoodiano. -

Film at Lincoln Center New Releases Series November 2019

Film at Lincoln Center November 2019 New Releases Parasite Synonyms Varda by Agnès Series Poetry and Partition: The Films of Ritwik Ghatak Jessica Hausner: The Miracle Worker Rebel Spirit: The Films of Patricia Mazuy Relentless Invention: New Korean Cinema, 1996-2003 Members save $5 Tickets: filmlinc.org Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center 144 West 65th Street, New York, NY Walter Reade Theater 165 West 65th Street, New York, NY NEW RELEASES: STRAIGHT FROM SOLD-OUT SCREENINGS AT NYFF! Playing This Month Showtimes at filmlinc.org Members save $5 on all tickets! Neon Courtesy of Kino Lorber HELD OVER BY POPULAR DEMAND! HELD OVER BY POPULAR DEMAND! OPENS NOVEMBER 22 “A dazzling work, gripping from beginning to “Astonishing, maddening, brilliant, hilarious, “A fascinating, informative, and reflective end, full of big bangs and small wonders.” obstinate, and altogether unmissable.” swan song that gives Varda the final word.” –Time Out New York –IndieWire –Tina Hassannia, Globe and Mail Parasite Synonyms Varda by Agnès Dir. Bong Joon Ho, South Korea, 132m In Bong Dir. Nadav Lapid, France/Israel/Germany, Dir. Agnès Varda, France, 120m When Agnès Joon Ho’s exhilarating new film, a threadbare 123m In his lacerating third feature, director Varda died earlier this year at age 90, the world family of four struggling to make ends meet Nadav Lapid’s camera races to keep up with the lost one of its most inspirational cinematic gradually hatches a scheme to work for, and as adventures of peripatetic Yoav (Tom Mercier), radicals. From her neorealist-tinged 1954 fea- a result infiltrate, the wealthy household of an a disillusioned Israeli who has absconded to ture debut La Pointe Courte to her New Wave entrepreneur, his seemingly frivolous wife, and Paris following his military training. -

Ad1c13b165149a9eb1367192fcf

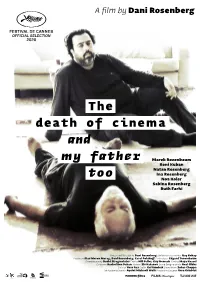

a film by Dani Rosenberg 2020 - Israel - Comedy, Drama - 1.85 - 100 min Screenings TUE JUN 23rd - 11:30 - RIVIERA 13 THU JUN 25th - 13:30 - RIVIERA 8 INTERNATIONAL SALES INTERNATIONAL PRESS FILMS BOUTIQUE CLAUDIATOMASSINI + ASSOCIATES Köpenicker Str. 184. 10997 Berlin, Germany International Film Publicity Tel + 49 30 69 53 78 50 Mobile:+49 173 205 5794 www.filmsboutique.com [email protected] [email protected] www.claudiatomassini.com Synopsis A father and son try to freeze time through cinema. While the father is unsentimental in his approach toward his last days, his son disconnects from reality in a desperate attempt to see his father as a hero. Although in the fictional story, Tel Aviv goes up in flames the father’s real world does not end with a bang but a slow vanishing whimper. Crew Director DANI ROSENBERG Screenwriter DANI ROSENBERG, ITAY KOHAY Production Company PARDES FILMS Producers STAV MORAG MERON, DANI ROSENBERG, CAROL POLAKOFF Co-producers EDGARD TENEMBAUM Cinematographer DAVID STRAGMEISTER Editor NILLI FELLER, GUY NEMESH Casting MAYA KESSEL Sound Designer NEAL GIBS Cast Yoel Edelstein MAREK ROZENBAUM Assaf Edelstein RONI KUBAN Nina Edelstein / Herself INA ROSENBERG Zohar Edelstein NOA KOLER NATAN ROSENBERG SABINA ROSENBERG Sabina Edelstein RUTH FARHI Gideon Edelstein URI KLAUZNER Director’s Notes “As a boy, I used to marvel that the letters in a closed book did not get scrambled and lost overnight”—The Aleph, Jorge Luis Borges The desire to preserve time is to believe in eternity, use the camera to stop the future, much like Scheherazade told her stories to postpone the inevitable end. -

PARIS RDV 2014 +33 6 84 37 37 03 | [email protected]

PARIS OFFICE: 5, rue Darcet, 75017 Paris, France www.le-pacte.com Tel: +33 1 44 69 59 59 Fax: +33 1 44 69 59 42 COMPLETED COMPLETED LIFE OF RILEY AMAZONIA WE COME AS FRIENDS THE LAST OF THE UNJUST IN (POST-)PRODUCTION THE REFEREE SALT OF THE EARTH WRONG COPS QUEEN & COUNTRY IN PRODUCTION HIPPOCRATES THE KINDERGARTEN TEACHER SCREENING AT THE MARKET WILD LIFE THE DUNE METAMORPHOSES LULU IN THE NUDE LIBRARY AT THE PARIS RDV LE GRAND HOTEL 2, RUE SCRIBE Camille Neel | Head of Sales PARIS RDV 2014 +33 6 84 37 37 03 | [email protected] Nathalie Jeung | Sales Executive +33 6 60 58 85 33 | [email protected] Arnaud Aubelle | Festivals +33 6 76 46 40 86 | [email protected] Lulu in the Nude LULU IN THE NUDE Sat. 11th 13:00 Gaumont Capucines 5 THE DUNE Mon. 13th 15:00 Gaumont Premier 3 Completed Based on the play by Alan Ayckbourn, also author of Smoking/No Smoking. A FILM BY ALAIN RESNAIS In the English countryside, the life of three couples is upset for a few months, from Spring to Fall, by the enigmatic behavior of their friend George Riley. When general practitioner Dr. Colin inadvertently tells his wife Kathryn that his patient George Riley does not have more than a few months to live, he doesn’t know that Riley was Kathryn’s first love. Both spouses, who are rehearsing a play with their local amateur theatre company, convince George to join them. It allows George, among other things, to play strong love scenes with Tamara, who is married to Jack, Producer: F comme Film his best friend, a rich businessman and unfaithful husband. -

University of Cambridge Tribute to the Jerusalem Sam

PROGRAM / SCHEDULE ALL SESSIONS WILL BEGIN AT 19:00 SESSION 1 THURSDAY - 21.1.16 changing israeli cinema from within Renen Schorr, founder-director of the Jerusalem Sam Spiegel Film School and The Mutes’ House, screening and conversation with award winning director Tamar Kay SESSION 2 THURSDAY - 28.1.16 footsteps in jerusalem Graduates homage (90’) to David Perlov’s iconic documentary, In Jerusalem fifty years later. Guest: Dr. Dan Geva SESSION 3 THURSDAY - 4.2.16 the conflict through the eyes of the jsfs students A collection of shorts (1994-2014), a retrospective curated by Prof. Richard Peña (82’) Guest: Yaelle Kayam SESSION 4 THURSDAY - 11.2.16 a birth of a filmmaker Nadav Lapid’s student and short films Guest: Nadav Lapid SESSION 5 THURSDAY - 18.2.16 the new normal haredi jew in israeli cinema Yehonatan Indurksy’s films Guest: Yehonatan Indursky SESSION 6 THURSDAY - 25.2.16 in search of a passive israeli hero Elad Keidan’s films Guest: Elad Keidan SESSION 7 THURSDAY - 3.3.16 the “mizrahi” (OF MIDDLE-EASTERN EXTRACTION) IS THE ARABIC JEW David Ofek’s films and television works Guest: David Ofek SESSION 8 THURSDAY - 10.3.16 revenge of the losers Talya Lavie’s films Guest: Talya Lavie UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE PRESENTS: BETWEEN Escapism and Strife A TRIBUTE TO THE JERUSALEM SAM SPIEGEL FILM SCHOOL In 1989 the Israeli film and television industry was changed forever when the first Israeli national film school was established in Jerusalem. Since then and for the past 25 years, the School, later renamed the Sam Spiegel Film School, graduated many of Israel’s leading film and television creators, who changed the film and television industry in Israel and were the engine for its renaissance, both in Israel and abroad. -

University of Cambridge Tribute to Jerusalem Sam Spiegel Film School

PROGRAM / SCHEDULE ALL SESSIONS WILL BEGIN AT 19:00 SESSION 1 THURSDAY - 21.1.16 changing israeli cinema from within Renen Schorr, founder-director of the Jerusalem Sam Spiegel Film School and The Mutes’ House, screening and conversation with award winning director Tamar Kay SESSION 2 THURSDAY - 28.1.16 footsteps in jerusalem Graduates homage (90’) to David Perlov’s iconic documentary, In Jerusalem fifty years later. Guest: Dr. Dan Geva SESSION 3 THURSDAY - 4.2.16 the conflict through the eyes of the jsfs students A collection of shorts (1994-2014), a retrospective curated by Prof. Richard Peña (82’) Guest: Yaelle Kayam SESSION 4 THURSDAY - 11.2.16 a birth of a filmmaker Nadav Lapid’s student and short films Guest: Nadav Lapid SESSION 5 THURSDAY - 18.2.16 the new normal haredi jew in israeli cinema Yehonatan Indurksy’s films Guest: Yehonatan Indursky SESSION 6 THURSDAY - 25.2.16 in search of a passive israeli hero Elad Keidan’s films Guest: Elad Keidan SESSION 7 THURSDAY - 3.3.16 the “mizrahi” (OF MIDDLE-EASTERN EXTRACTION) IS THE ARABIC JEW David Ofek’s films and television works Guest: David Ofek SESSION 8 THURSDAY - 10.3.16 revenge of the losers Talya Lavie’s films Guest: Talya Lavie UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE PRESENTS: BETWEEN Escapism and Strife A TRIBUTE TO THE JERUSALEM SAM SPIEGEL FILM SCHOOL In 1989 the Israeli film and television industry was changed forever when the first Israeli national film school was established in Jerusalem. Since then and for the past 25 years, the School, later renamed the Sam Spiegel Film School, graduated many of Israel’s leading film and television creators, who changed the film and television industry in Israel and were the engine for its renaissance, both in Israel and abroad. -

Pini Tavger's 'Pinhas' Wins 6Th Edition of Sam Spiegel Film Lab | Variety

Pini Tavger’s ‘Pinhas’ Wins 6th Edition of Sam Spiegel Film Lab | Variety http://variety.com/2017/film/global/pini-tavgers-pinhas-wins-6th-edition-of... JULY 16, 2017 | 06:35AM PT YOSSI ZWECKER(C) [email protected] Pini Tavger’s “Pinhas,” a film project exploring the Jewish identity through the eyes of a 12-year old boy, won the top prize at the sixth edition of Sam Spiegel International Film Lab, a program running alongside Jerusalem Film Festival. “Pinhas,” which marks the feature debut of actor-director Tavger and is based on his student short film, received a production grant worth $50,000 from the Beracha Foundation. Haim Mecklberg (pictured above with Tavger) at Tel Aviv- based outfit 2-Team Productions (“Sand Storm”) is producing. The project centers on a young boy, Pinhas, and his hard-working, heretic mother who are new immigrants from Russia living in Israel. The story revolves around Pinhas’s relationship with a religious man who helps him find a sense of belonging and initiate him to judaism against his mother’s will. The Sam Spiegel Lab’s jury was presided over Hengameh Panahi, the founder 1 of 4 8/2/17, 6:42 PM Pini Tavger’s ‘Pinhas’ Wins 6th Edition of Sam Spiegel Film Lab | Variety http://variety.com/2017/film/global/pini-tavgers-pinhas-wins-6th-edition-of... and president of Paris-based outfit Celluloid Dreams, and included Beki Probst, president of the European Film Market, Carlo Chatrian, Locarno’s director, Laurent Hassid, the head of foreign film acquisition at Canal Plus, Cédomir Kolar (“Album”), Katriel Schory, the director of the Israel Film Fund, and Vincenzo Bugno, project manager of the World Cinema Fund. -

God of the Piano by Itay Tal Cast Production

God Of The Piano by Itay Tal Cast Production Naama Preis (Anat), Zeev Shimshoni (Arieh), Andi Levi (Idan), Producers: Itay Tal, Shani Egozin Leora Rivlin (Or), Eli Gornstein (Baruch), Ami Weinberg (Avri), Production Company: Movie Makers Ezra Dagan (Yoel), Shimon Mimran (Raphael), Ron Bitterman (Hanan), Alon Openhaim (Dror). International Sales Crew Film Republic Director and Scriptwriter: Itay Tal Director of Photography: Meidan Arama God Of The Piano Executive Producer: Hila Ben-Shushan Editing: Itay Tal by Itay Tal Music: Roie Shpigler, Hillel Teplitzky Music Performance: Eran Zvirin 80 min, colour, Israel 2019 Production Design: Shir Kleiman Lighting Director: Raanan Berger Costume Design: Neta Shenitzer Sound: Nir Aviam Sound Mixer: Shahaf Vegshel / DB studios Colorist: Peleg Levi Casting: Itay Tal, Shani Egozin, Hila Ben-Shushan Synopsis Music is all she has. Anat has never been able to reach her father’s musical standards and her hope for fulfillment is de- pendent on the embryo that is in her womb. When the baby is born deaf she cannot accept it and takes extreme measures to ensure that her child will be the composer that her father always wanted. But when the young pianist doesn’t respect his grandfather, his own glory remains uncertain. Now, Anat will have to stand up to her father. Film’s Trailer Directors Statement When the idea for this movie first came to mind, I had Why is it that for so many years I dreamt about playing the yet to come to the realization that there would be a piano piano, but never dared to buy one? Why is it that when I involved. -

The Kindergarten Teacher PK

THE KINDERGARTEN TEACHER Directed by | Sara Colangelo Cast | Maggie Gyllenhaal, Parker Sevak, Michael Chernus and Gael García Bernal Running time | 97 minutes Certificate | TBC Language | English UK release date | 8th February 2019 Press information | Saffeya Shebli | [email protected] | 020 7377 1407 1 SYNOPSIS When a Staten Island kindergarten teacher discovers what may be a gifted five-year-old student in her class, she becomes fascinated with the child - spiralling downward on a dangerous and desperate path in order to nurture his talent. SARA COLANGELO, DIRECTOR STATEMENT THE KINDERGARTEN TEACHER is a psychological thriller about a woman, named Lisa Spinelli, who lives a mundane life in Staten Island and teaches at a local kindergarten. She takes night classes in poetry and is a forgettable student. But she trudges forth, still enjoying the artistic pursuit, with a certain understanding of her mediocrity. One day she discovers that a boy in her class has a prodigious gift for poetry and, from that moment forward, does everything in her power to support and cultivate his talent—going to dangerous extremes to deliver his art to the world. This film is an exciting project for me because it is the story of, predominantly, one woman. It has given me an opportunity to delve deeply into the fascinating psychology of Lisa-- to explore her inner-workings, her good intentions gone awry, and her desire to live a more meaningful life. The story also provides what I think is a nuanced, complex lead role for a 40- something woman— an unfortunate rarity in both Hollywood and the independent film industry. -

The Millennial Antinostalgic: Yoav in Nadav Lapid's Synonymes

The Millennial Antinostalgic: Yoav in Nadav Lapid’s Synonymes Jora Vaso, Pomeranian University in Slupsk, [email protected] Volume 9.1 (2021) | ISSN 2158-8724 (online) | DOI 10.5195/cinej.2021.288 | http://cinej.pitt.edu Abstract In contemporary, transnational exilic cinema exile an artist is made in an exilic journey. The 21st century journey departs from entirely opposite premises than those of the ancient journey, namely with the desire to escape one’s birthplace. The aim of the exile has also transformed: from a necessary step to secure one’s livelihood or even life, it has become one of exploration. Rather than the desire to settle elsewhere or to eventually return home, the exile sets on an open-ended, exploratory journey the premise of which is finding oneself. In this, the physical journey has come to resemble the metaphysical one of the artist. The exile departs from a physical place and journeys into a metaphysical space, geography becoming secondary while still being necessary. This journey is best recounted in the film Synonymes (2019) by Israeli director Nadav Lapid, an autobiographical tale that chronicles the director’s own exile from Israel to Paris and captures his journey toward becoming an artist. The paper references two prominently antinostalgic authors: 20th century Polish writer Witold Gombrowicz and Polsih-Jewish writer Henryk Grynberg. Keywords: Antinostalgia; millennial exile; modern exile; jewish exile, allegorical thinking New articles in this journal are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 United States License. This journal is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D-Scribe Digital Publishing Program and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press The Millennial Antinostalgic: Yoav in Nadav Lapid’s Synonymes Jora Vaso Introduction Nadav’s Lapid autobiographical film Synonymes (2019) is the story of Yoav, an Israeli youth who arrives “in France to flee from Israel,” (Lapid, 2019, 18:15) entirely unaware that he has brought Israel along with him. -

The Cakemaker a Film by Ofir Raul Graizer

presents THE CAKEMAKER A FILM BY OFIR RAUL GRAIZER Starring Tim Kalkhof, Sarah Adler, Roy Miller, Zohar Strauss and Sandra Sade PRESS NOTES Official Selection: Karlovy Vary International Film Festival, WINNER, The Ecumenical Jury Award Chicago International Film Festival Palm Springs International Film Festival New York Jewish Film Festival Miami Jewish Film Festival, WINNER, Critics Award BFI London Film Festival Country of Origin: Israel | Germany Format: DCP/2.39/Color Sound Format: 5.1 Surround Sound Running Time: 105 minutes Genre: Drama Not Rated In Hebrew, German and English with English Subtitles National Press Contact: Jenna Martin / Marcus Hu Strand Releasing Phone: 310.836.7500 [email protected] [email protected] Please download photos from our website: https://strandreleasing.com/films/the-cakemaker/ LOGLINE A German pastry maker travels to Jerusalem in search for the wife and son of his dead lover. SYNOPSIS Thomas, a young German baker, is having an affair with Oren, an Israeli married man who has frequent business visits in Berlin. When Oren dies in a car crash in Israel, Thomas travels to Jerusalem seeking for answers regarding his death. Under a secret identity, Thomas infiltrates into the life of Anat, his lover’s newly widowed wife. The encounter with the unfamiliar reality will make Thomas involved in Anat's life in a way far beyond his anticipation, and to protect the truth he will stretch his lie to a point of no return. DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT “The Cakemaker” is a melodrama set in Jerusalem. The narrative moves, the settings and the characters, are of my own private memory and experience that have shaped during the 6.5 years I’ve worked on this film.