1 “Who Is Not Engaged in Trying to Leave a Mark, to Engrave His Image

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Galenroth.Pdf

1 THE COLONY-a new work by Galen Roth Originally performed in the New Works Lab in the Drake Theatre Union, The Ohio State University – Columbus, Ohio on May 8th, 9th, and 10th 2009. Author / Director.............Galen Roth Artistic Director...............Chris Roche Script Facilitator..............Bernhard Malkmus Lights.................................Kevin Duchon Stage Manager..................Andrea Schimmoeller Cast: Morris................................Jessi Biggert Angela................................Jessica Studer Karen.................................Barbie Papalios Evan...................................Ben Sostrom Artie...................................Mark Hale, Jr. Melody................................Kelsey Bates Guitarist / New Music.......Chris Ray Special thanks to Mark Shanda, Mandy Fox, Alan Woods, Kristine Kearney, and The Ohio State University Theatre Department. The set is divided into seven areas: one room each for Angela, Artie, Karen, Melody and Morris. Karen’s room is in the center, with the others circled around it. The remaining two areas are a small alcove representing a closet, and another small area in front of Karen’s room, which is the entrance to the Colony. All along the walls of the entire space are pictures: photographs and paintings. They are facing backward, for now. As the audience comes in, the artists all lay down a floor pattern in their respective areas. As they finish, Angela goes around and connects all the floor patterns, while the artists do their work. This goes on for a while, so we get the feeling of an existing, working community. Bookend i Morris crosses to Angela’s room. Angela is blind, her eyes covered by gauze. Morris: I need your help. Angela: I hate doing this for you. Morris: I can’t imagine why. Angela: Don’t get smart with me. -

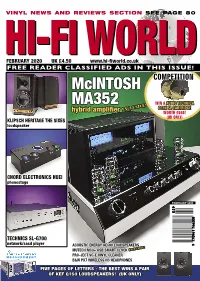

Mcintosh MA352 HYBRID VALVE AMPLIFIER 10 Transistor Power but with Valve Sound

VINYL NEWS AND REVIEWS SECTION SEE PAGE 80 HI-FIHI-FIFEBRUARY 2020 UK £4.50 WORLDWORLDwww.hi-fiworld.co.uk FREE READER CLASSIFIED ADS IN THIS ISSUE! McINTOSH COMPETITION MA352 WIN A AUDIO TECHNICA ! Exclusive OC9X SL CARTRIDGE hybrid amplifier WORTH £660! (UK ONLY) KLIPSCH HERITAGE THE SIXES loudspeaker CHORD ELECTRONICS HUEI phonostage FEBRUARY 2020 TECHNICS SL-G700 network/sacd player ACOUSTIC ENERGY AE500 LOUDSPEAKERS SIVE! MUTECH MC3+ USB SMART CLOCK EXCLU PRO-JECT VC-E VINYL CLEANER MEASUREMENT B&W PX7 WIRELESS NC HEADPHONES FIVE PAGES OF LETTERS - THE BEST WINS A PAIR OF KEF Q150 LOUDSPEAKERS! (UK ONLY) [master] The definitive version. Ultimate performance, bespoke audiophile cable collection Chord Company Signature, Sarum and ChordMusic form the vanguard of our cable ranges. A master collection that features our latest conductor, insulation and connector technology. High-end audiophile quality at a realistic price and each one built to your specific requirements. Arrange a demonstration with your nearest Chord Company retailer and hear the difference for yourself. Designed and hand-built in England since 1985 by a dedicated team of music-lovers. Find more information and a dealer locator at: www.chord.co.uk chordco-ad-HFW-MAR19-MASTER-002a.indd 1 07/05/2019 13:57:32 welcome EDITOR alves can be a bit troublesome. If you’re lucky big ones responsible Noel Keywood for producing power will last a few thousand hours, but then need e-mail: [email protected] replacing. However, small ones that don’t dissipate power will sol- dier on past 10,000 hours – and what’s more they cost little, in the DESIGN EDITOR £10-£20 region. -

PEGODA-DISSERTATION-2016.Pdf (3.234Mb)

© Copyright by Andrew Joseph Pegoda December, 2016 “IF YOU DO NOT LIKE THE PAST, CHANGE IT”: THE REEL CIVIL RIGHTS REVOLUTION, HISTORICAL MEMORY, AND THE MAKING OF UTOPIAN PASTS _______________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Andrew Joseph Pegoda December, 2016 “IF YOU DO NOT LIKE THE PAST, CHANGE IT”: THE REEL CIVIL RIGHTS REVOLUTION, HISTORICAL MEMORY, AND THE MAKING OF UTOPIAN PASTS ____________________________ Andrew Joseph Pegoda APPROVED: ____________________________ Linda Reed, Ph.D. Committee Chair ____________________________ Nancy Beck Young, Ph.D. ____________________________ Richard Mizelle, Ph.D. ____________________________ Barbara Hales, Ph.D. University of Houston-Clear Lake ____________________________ Steven G. Craig, Ph.D. Interim Dean, College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences Department of Economics ii “IF YOU DO NOT LIKE THE PAST, CHANGE IT”: THE REEL CIVIL RIGHTS REVOLUTION, HISTORICAL MEMORY, AND THE MAKING OF UTOPIAN PASTS _______________ An Abstract of A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Andrew Joseph Pegoda December, 2016 ABSTRACT Historians have continued to expand the available literature on the Civil Rights Revolution, an unprecedented social movement during the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s that aimed to codify basic human and civil rights for individuals racialized as Black, by further developing its cast of characters, challenging its geographical and temporal boundaries, and by comparing it to other social movements both inside and outside of the United States. -

The Affordable Care Act Health Exchange Is Open Rathbun Insurance Is Available to Help with Information and Enrollment Assistance

FREE A newspaper for the rest of us www.lansingcitypulse.com January 14-20, 2015 a newspaper for the rest of us www.lansingcitypulse.com HIGH-IGH-SPEED IINTERNET HIGHWAYIGHWAY ISIS COMING TO YOUR NEIGHBORHOOD • PAGE 9 The Affordable Care Act Health Exchange is Open Rathbun Insurance is available to help with information and enrollment assistance. Enrollment open from Jan 16th to Feb 15th for coverage starting March 1, 2015 After this point special enrollment requirements apply (517) 482-1316 www.rathbunagency.com 2 www.lansingcitypulse.com City Pulse • January 14, 2015 Newsmakers HOSTED BY BERL SCHWARTZ THIS WEEK: MSU IN MALI STEPHEN ESQUITH DEAN OF THE MSU RESIDENTIAL COLLEGE IN THE ARTS AND HUMANITIES MOUSSA TRAORE MSU STUDENT FROM MALI MY18TV! 10 A.M. EVERY SATURDAY COMCAST CHANNEL 16 LANSING 7:30 P.M. EVERY FRIDAY City Pulse • January 14, 2015 www.lansingcitypulse.com 3 4 www.lansingcitypulse.com City Pulse • January 14, 2015 VOL. 14 Feedback ISSUE 22 credit and a restoration of some of the mon- Sales tax to fix roads makes sense The sales tax to fix roads is a good plan; ey cut from our schools. And it is less regres- (517) 371-5600 • Fax: (517) 999-6061 • 1905 E. Michigan Ave. • Lansing, MI 48912 • www.lansingcitypulse.com we should pass it. It comes with a restoration sive than Mickey Hirten makes it out to be; ADVERTISING INQUIRIES: (517) 999-5061 of the full low-income earned income tax certainly less regressive than using increased PAGE CLASSIFIED AD INQUIRIES: (517) 999-5066 gas tax to “fix roads.” or email [email protected] Look at what low-income people have to 5 Have something to say about a local issue PUBLISHER • Berl Schwartz buy: food, rent, medical care, utilities, and [email protected] • (517) 999-5061 or an item that appeared in our pages? gas. -

Lubbock on Everything: the Evocation of Place in the Music of West Texas

02-233 Ch16 9/19/02 2:27 PM Page 255 16 Lubbock on Everything: The Evocation of Place in the Music of West Texas Blake Gumprecht The role of landscape and the importance of place in literature, poetry, the visual arts, even cinema and television are well established and have been widely discussed and written about. Think of Faulkner’s Mississippi, the New England poetry of Robert Frost, the regionalist paintings of John Steuart Curry, or, in a contemporary sense, the early movies of Barry Levinson, with their rich depictions of Baltimore. There are countless other examples. Texas could be considered a protagonist in the novels of Larry McMurtry. The American Southwest is central to the art of Georgia O’Keeffe. New York City acts as far more than just a setting for the films of Woody Allen. The creative arts have helped shape our views of such places, and the study of works in which particular places figure prominently can help us better understand those places and human perceptions of them.1 Place can also be important to music, yet this has been largely overlooked by scholars. The literature on the subject, in fact, is nearly nonexistent. A sim- ple search of a national library database, for example, retrieved 295 records under the subject heading “landscape in literature” and more than 1,000 un- der the heading “landscape in art,” but a similar search using the phrase “landscape in music” turned up nothing.2 This line of inquiry is so poorly de- veloped that no equivalent subject heading has been established. -

A Year in the Life of Bottle the Curmudgeon What You Are About to Read Is the Book of the Blog of the Facebook Project I Started When My Dad Died in 2019

A Year in the Life of Bottle the Curmudgeon What you are about to read is the book of the blog of the Facebook project I started when my dad died in 2019. It also happens to be many more things: a diary, a commentary on contemporaneous events, a series of stories, lectures, and diatribes on politics, religion, art, business, philosophy, and pop culture, all in the mostly daily publishing of 365 essays, ostensibly about an album, but really just what spewed from my brain while listening to an album. I finished the last essay on June 19, 2020 and began putting it into book from. The hyperlinked but typo rich version of these essays is available at: https://albumsforeternity.blogspot.com/ Thank you for reading, I hope you find it enjoyable, possibly even entertaining. bottleofbeef.com exists, why not give it a visit? Have an album you want me to review? Want to give feedback or converse about something? Send your own wordy words to [email protected] , and I will most likely reply. Unless you’re being a jerk. © Bottle of Beef 2020, all rights reserved. Welcome to my record collection. This is a book about my love of listening to albums. It started off as a nightly perusal of my dad's record collection (which sadly became mine) on my personal Facebook page. Over the ensuing months it became quite an enjoyable process of simply ranting about what I think is a real art form, the album. It exists in three forms: nightly posts on Facebook, a chronologically maintained blog that is still ongoing (though less frequent), and now this book. -

The Political Kiaesthetics of Contemporary Dance:—

The Political Kinesthetics of Contemporary Dance: Taiwan in Transnational Perspective By Chia-Yi Seetoo A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Miryam Sas, Chair Professor Catherine Cole Professor Sophie Volpp Professor Andrew F. Jones Spring 2013 Copyright 2013 Chia-Yi Seetoo All Rights Reserved Abstract The Political Kinesthetics of Contemporary Dance: Taiwan in Transnational Perspective By Chia-Yi Seetoo University of California, Berkeley Doctor of Philosophy in Performance Studies Professor Miryam Sas, Chair This dissertation considers dance practices emerging out of post-1980s conditions in Taiwan to theorize how contemporary dance negotiates temporality as a political kinesthetic performance. The dissertation attends to the ways dance kinesthetically responds to and mediates the flows of time, cultural identity, and social and political forces in its transnational movement. Dances negotiate disjunctures in the temporality of modernization as locally experienced and their global geotemporal mapping. The movement of performers and works pushes this simultaneous negotiation to the surface, as the aesthetics of the performances registers the complexity of the forces they are grappling with and their strategies of response. By calling these strategies “political kinesthetic” performance, I wish to highlight how politics, aesthetics, and kinesthetics converge in dance, and to show how political and affective economies operate with and through fully sensate, efforted, laboring bodies. I begin my discussion with the Cursive series performed by the Cloud Gate Dance Theatre of Taiwan, whose intersection of dance and cursive-style Chinese calligraphy initiates consideration of the temporal implication of “contemporary” as “contemporaneity” that underlies the simultaneous negotiation of local and transnational concerns. -

Country Country Y R T N U

2 COUNTRY COUNTRY MARK ABBOTT ESSEN TIAL CD RCA 67621 € 19.50 I RECKON I’M A TEXAN ‘TILL I FOR THE RECORD 2-CD CD RCA 67633 € 32.90 DIE CD 131 01 € 21.90 TWEN TI ETH CENTURY CD RCA 67793 € 9.90 LEGEND ARY 3-CD ROY ACUFF 8 (AUSTRA LIA) CD RCA 94404 19.90 THE KING OF COUNTR Y € MUSIC 2-CD BCD 15652 € 30.68 GARY ALLAN NIGHT TRAIN TO MEMPHIS ALRIGHT GUY CD MCA 170201 € 21.90 2-CD CD CTY 211001 € 14.50 IT WOULD BE YOU CD MCA 70012 € 20.50 HEAR THE MIGHTY RUSH OF JOHNNIE ALLAN ENGINE CD JAS 3532 € 15.34 PROM ISED LAND CD CHD 380 € 17.90 OH BOY CLAS SICS PRES ENT... CD OBR 409 19.50 € JASON ALLEN TRACE ADKINS SOMETHING I DREAMED CD D 9000 € 19.90 GREATEST HITS - ENHANCED REX ALLEN 8 CD CD CAP 81512 € 21.50 VOICE OF THE WEST BCD 15284 € 15.34 BILL ANDERSON 20 GREATEST HITS CD BA 239 € 20.50 A LOT OF THINGS DIFFERENT CD VSD 66262 € 20.50 JOHN ANDERSON BACK TRACKS CD BR 0601 € 19.50 NOBODY’S GOT IT ALL CD CK 63990 € 20.50 SOME HOW, SOME WAY, SOME - DAY (EARLY TRACKS) CD PSR 90624 € 21.50 LYNN ANDERSON ROSE GARDEN / YOU’RE MY MAN CD 494897 € 16.90 8 LIVE AT BILLY BOB’S TEXAS CD SMG 5010 € 15.90 Then They Do- (This Ain’t) No Thinkin’ Thing- The Rest Of Mine- Chrome- I’m Tryin’- There’s A Girl In Texas- Every Light In The House- Don’t Lie- I Left Some thing Turned On At Home- Big Time- Lonely Won’t Leave Me Alone- Help Me Under stand- More- Welcome To Hell · (2003/CAPITOL) 14 tracks MORE.. -

CBTA Takes on Food Waste Looking Ahead to Convention 2019

NEWSLETTER 2019 SPRING • VOLUME 105, NUMBER 1 CBTA Takes on Food Waste By Celina Scott-Buechler SP13 CB14 TA16 ew aspects of daily life are as elemental and multifaceted as food” – so begins the 2013 TASP seminar description, “FOOD.” “FFood is critical not only for human nutrition but also for the construction of culture, morality, and community. Convention Proceedings (in the early days, Convention Minutes) as early as the 1910s discuss food as a vessel for moral or immoral behavior. In 1916, the Dean of the Student Body at the Beaver River Power Company writes in his report, “Few questions are of more vital importance to the Association than that of indulgence, which springs from feeling.” He continues on to decry “a strong tendency [in the student body] to indulge yourselves; this is your weakness. You want to smoke; you want to drink; you want to be good fellows; you want to swear; you want to do as you d-n please; you want to eat candy and rich food.” He concludes by asking, “Do you say these matters are trivial? A second of time seems trivial, but time and eternity are made up of trivial seconds. Altogether these matters of indulgence constitute, perhaps, our biggest hindrance to success.” Today’s Association does not, as a whole, ascribe to such asceticism. To the contrary, good food (sometimes rich, sometimes not) has become an important consideration Pasadena Branch members indulging at Knott’s Berry Farm, circa 1949-50 for its programs. Last Convention, I overheard an under-slept Association continued on page 3 Looking Ahead to Convention Also in this issue: 2019 Michigan Branchmember Stresses Value of International Exchange Programs .................................2 By Hammad Ahmed SP02 TA10, TA President 2018-19 Birthing a Revolution with Radical Doulas ...................4 ne of my two goals this year as President TASS Alum Wins Award, Donates Prize to Telluride ......5 Ois to make our board meetings more effective. -

Student Elections Receive Poor Turnout

State University of New York at Fredonia The Issue No. 4, Volume XXV LeaderWednesday September 25, 2013 Fredonia professor men's soccer drops premieres short film non-conference b-1 games A-6 Student elections receive poor turnout McMahon MARSHA COHEN is the man Special to The Leader WENDY MAHNK Every year a group of ambitious and Special to The Leader motivated SUNY Fredonia students aim to become the voice for their respective In honor of Constitution Day, class. They rely on their peers’ trust and Kevin McMahon, an award winning word that they will vote for them, and, in political author, was the guest speaker return, they will be the best representa- at the Political Science Department tives they can be. sponsored event. McMahon, formerly On Sept. 17 and 18, SUNY Fredonia’s a professor of political science at the Student Association held their annual State University of Fredonia, is cur- class elections. Every class, ranging from rently a professor of political science freshman to seniors, were able to elect at Trinity College in Connecticut. their class president and class represen- The lecture focused around tatives for the 2013-14 school year. The McMahon’s most recently released winners were announced Wednesday book, Nixon’s Court: His Challenge night and were sworn in at Thursday’s to Judicial Liberalism and Its Political GA meeting. Consequences (University of Chicago Poll results showed an extremely press, 2011). His book was selected low turn-out. With an estimated 86 as a 2012 CHOICE Outstanding senior, 52 junior, 43 sophomore and 22 Academic Title, while his previous freshman votes counted, an exceedingly book Reconsidering Roosevelt on low percentage of students voiced their Race: How the Presidency Paved the opinion in this year’s elections. -

June 2012 #173.Indd

NashvilleMusicGuide.com 1 NashvilleMusicGuide.com 2 NashvilleMusicGuide.com 1 48 Arcadius 71st Iroquois Steeplechase Executive Editor & CEO Randy Matthews Contents Letter from the Editor [email protected] 50 Memphis in May Nashville Music Guide had Nash- Field and have a lot of kid-friendly activities going on. We Managing Editor Amanda Andrews Got the Blues on Beale St. ville singing the blues at Winners on are involved in a celebrity tournament on Thursday, June [email protected] Features May 17th. The First Annual Blues 7th at Hard Rock from 2 til 4. It is for a new game called 52 NMG Blues Jam Jam rocked. The event was standing ‘You’ve Been Sentenced – Country Edition’. It will be a Director, Sales & Marketing Janell Webb 4 Heartland Idol Midtown Nashville [email protected] room only and was a huge success. We blast. Come out and play. Lauren Elizabeth Sings the Blues should do it every week.... well, that Sales & Marketing Hannah Ryans 5 Outlaw Country would contradict calling it our First Bonnaroo is this week as well, so the roads to Manches- [email protected] 54 Healing Power of Music Annual, now wouldn’t it? ter will be slow, but the musical line-up is just crazy. And Jason Roberson Intimate Evening with We would like to thank the Nashville I mean crazy good, not crazy insane, or ate too many Accounts Rhonda Smith Missouri’s Sweetest Blues Society, Strum Magazine, Jive, brownies that tasted funny - crazy. Check out our spread [email protected] 6 Darryl Worley Winners and HobNob Nashville for on Bonnaroo in this issue. -

Exhibition Guide

EXHIBITION GUIDE The impact of abuse and maltreatment lasts for a life time. Therefore, teach through dialogue, understanding and instilling values, and don’t leave a mark through hitting and humiliation The impact of abuse and maltreatment lasts for a life time. Therefore, teach through dialogue, understanding and instilling values, and don’t leave a mark through hitting and humiliation. This exhibition reveals various aspects of child maltreatment in Jordan through presenting painful and moving true stories from our society. Some of these stories became issues of public opinion and spread through media, while others took place around us but remained hidden and unknown. The exhibition aims at shedding light on these stories, so we can all work together towards: “Jordan free of child abuse and maltreatment.” The exhibition provides key messages against each of these unfortunate stories that are directed at children and parents. The content of the messages is about positive parenting methods that rely mainly on dialogue, understanding, communication and being a role model. These methods proved to be successful and effective in reinforcing positive behaviour and self discipline in children. “The Adventures of Looney Ballooney” is a platform created by the National Council for Family Affairs and the UNICEF, as a continuation of their efforts which aim at raising awareness of the importance of positive parenting within families, and warning them about the dangers of child abuse and maltreatment. “The Adventures of Looney Balloney” festival is one part of a comprehensive multi-sectoral national strategy, aiming at reducing the violence against children through raising community awareness and supporting the development of policies and programs, in order to protect children from violence, and change attitudes and behaviours, aiming in the end at eradicating all child maltreating practices.