“Rules in War – a Thing of the Past?” Keynote Address

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S/PV.8499 International Humanitarian Law 01/04/2019

United Nations S/ PV.8499 Security Council Provisional Seventy-fourth year 8499th meeting Monday, 1 April 2019, 3 p.m. New York President: Mr. Maas ...................................... (Germany) Members: Belgium ....................................... Mr. Pecsteen de Buytswerve China ......................................... Mr. Ma Zhaoxu Côte d’Ivoire ................................... Mr. Adom Dominican Republic .............................. Mr. Singer Weisinger Equatorial Guinea ............................... Mr. Esono Mbengono France ........................................ Mr. Le Drian Indonesia. Mr. Djani Kuwait ........................................ Sheikh Al Sabah Peru .......................................... Mr. Duclos Poland ........................................ Mr. Czaputowicz Russian Federation ............................... Mr. Kuzmin South Africa ................................... Mr. Matjila United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland .. Mr. Allen United States of America .......................... Mr. Cohen Agenda The promotion and strengthening of the rule of law in the maintenance of international peace and security International humanitarian law . This record contains the text of speeches delivered in English and of the translation of speeches delivered in other languages. The final text will be printed in the Official Records of the Security Council. Corrections should be submitted to the original languages only. They should be incorporated in a copy of the record and sent under the signature of a member of the delegation concerned to the Chief of the Verbatim Reporting Service, room U-0506 ([email protected]). Corrected records will be reissued electronically on the Official Document System of the United Nations (http://documents.un.org). 19-09349 (E) *1909349* S/PV.8499 International humanitarian law 01/04/2019 The meeting was called to order at 3.05 p.m. (spoke in English) Before giving the floor to our briefers, I would like Expression of thanks to the outgoing President to make a few short remarks. -

WOMEN & WAR Women & Armed Conflicts and the Issue of Sexual

European Union Institute for Security Studies WOMEN & WAR Women & Armed Conflicts and the issue of Sexual Violence REPORT Colloquium ICRC – EUISS, 30 September 2014 WWW.ICRC.ORG WWW.ISS.EUROPA.EU pàl_COLLOQUE_2.indd 2 25/04/10 20:10 This report derives from a colloquium on the theme of “Women and Armed Conflicts and the Issue of Sexual Violence” organized jointly by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS) which took place on 30 September 2014 in Brussels. The proceedings of this colloquium have been written by the speakers or by the Delegation of the ICRC in Brussels on the basis of audio recordings of the colloquium. The opinions expressed herein are not necessarily those of the EUISS nor the ICRC. International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Delegation to the EU, NATO and the Kingdom of Belgium Rue Guimard 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium tél. : +32 (0)2 286 58 70 [email protected] http://www.icrc.org/be Graphic Design by Studio Fifty Fifty, Brussels © ICRC, June 2015 Front cover : ICRC / VON TOGGENBURG, Christoph Printed in Waregem on 100% recycled paper by PrintConcept.be WOMEN & WAR Women & Armed Conflicts and the issue of Sexual Violence REPORT Colloquium ICRC – EUISS, 30 September 2014 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 OPENING 6 WELCOMING WORDS Dr Antonio Missiroli, Director of the EUISS, Mr François Bellon, Head of the ICRC Delegation to the EU, NATO and Kingdom of Belgium KEYNOTE ADDRESSES Ms Helga Schmid, Deputy Secretary General of the European External Action -

Assemblée Générale GENERALE

NATIONS UNIES A Distr. Assemblée générale GENERALE A/AC.96/954/Rev.1 5 octobre 2001 Original: FRANCAIS/ANGLAIS COMITE EXECUTIF DU PROGRAMME DU HAUT COMMISSAIRE Cinquante-deuxième session (Genève, 1 - 5 octobre 2001) EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OF THE HIGH COMMISSIONER'S PROGRAMME Fifty-second session (Geneva, 1 - 5 October 2001) LISTE DES PARTICIPANTS LIST OF PARTICIPANTS GE.01-02928 A/AC.96/954/Rev.1 page 2 TABLE DES MATIERES Pages I. ETATS 3 A. Etats membres 3 B. Etats représentés par des observateurs 34 II. OBSERVATEUR 58 III AUTRES OBSERVATEURS 58 IV. ORGANISATIONS INTERGOUVERNEMENTALES 60 A. Système des Nations Unies 60 1. Nations Unies 60 2. Institutions spécialisées 62 B. Autres organisations intergouvernementales 63 V. ORGANISATIONS NON GOUVERNEMENTALES 65 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. STATES 3 A. Member States 3 B. States represented by observers 34 II. OBSERVER 58 III. OTHER OBSERVERS 58 IV. INTERGOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS 60 A. United Nations system 60 1. United Nations 60 2. Specialized agencies 62 B. Other intergovernmental organizations 63 V. NON GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS 65 A/AC.96/954/Rev.1 page 3 I. ETATS - STATES A. Etats membres/Member States AFRIQUE DU SUD - SOUTH AFRICA Representative H.E. Mr. Sipho George Nene Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Permanent Representative to the United Nations Office at Geneva Alternate Representatives Mr. Kevin Brennan Deputy Director, Humanitarian Affairs, Department of Foreign Affairs Mr. Haiko E. Alfeld First Secretary, Permanent Mission to the United Nations Office at Geneva ALGERIE - ALGERIA Représentant S.E. M. Mohamed-Salah Dembri Ambassadeur extraordinaire et plénipotentiaire, Représentant permanent auprès de l'Office des Nations Unies à Genève Représentant suppléant M. -

August 2014 Forecast.Indd

August 2014 Monthly Forecast 2 In Hindsight: The Overview Security Council’s Action on Downed Passenger Flights The UK will hold the presidency of the Coun- • the situation in Sudan and the work of AU-UN 3 Status Update since our cil in August. An open debate on the role of the Hybrid Operation in Darfur (UNAMID), like- July Forecast Security Council in conflict prevention, with ly by Joint Special Representative Mohamed 4 briefings by Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon and Ibn Chambas; 5 South Sudan High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pil- • developments in Libya by Special Representa- 7 Sudan and South lay, is planned. A high-level debate is envisaged tive Tarek Mitri; and Sudan on the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to be • the situation in the Central African Republic presided by the UK Minister for Africa, Mark by Special Representative Babacar Gaye. 9 Sudan (Darfur) Simmonds, with Special Representative Martin Briefings in consultations are likely on: 10 Central African Kobler and exiting Special Envoy to the Great • the implementation of resolution 2118 regard- Republic Lakes Region Mary Robinson as likely briefers. A ing the destruction of Syria’s chemical weap- 12 Democratic Republic of debate on Kosovo is expected, with a briefing by ons, by Sigrid Kaag, Special Coordinator of the Congo Special Representative Farid Zarif, by video tele- the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemi- 14 Burundi conference (VTC). Also in August, the Council is cal Weapons-UN Joint Mission (by VTC); 15 Guinea-Bissau planning a visiting mission to -

The Human Cost of Nuclear Weapons

The human cost Autumn 2015 97 Number 899 Volume of nuclear weapons Volume 97 Number 899 Autumn 2015 Volume 97 Number 899 Autumn 2015 Editorial: A price too high: Rethinking nuclear weapons in light of their human cost Vincent Bernard, Editor-in-Chief After the atomic bomb: Hibakusha tell their stories Masao Tomonaga, Sadao Yamamoto and Yoshiro Yamawaki The view from under the mushroom cloud: The Chugoku Shimbun newspaper and the Hiroshima Peace Media Center Tomomitsu Miyazaki Photo gallery: Ground zero Nagasaki Akitoshi Nakamura Discussion: Seventy years after Hiroshima and Nagasaki: Reflections on the consequences of nuclear detonation Tadateru Konoé and Peter Maurer Nuclear arsenals: Current developments, trends and capabilities Hans M. Kristensen and Matthew G. McKinzie Pursuing “effective measures” relating to nuclear disarmament: Ways of making a legal obligation a reality Treasa Dunworth The human costs and legal consequences of nuclear weapons under international humanitarian law Louis Maresca and Eleanor Mitchell Chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear events: The humanitarian response framework of the International Committee of the Red Cross Gregor Malich, Robin Coupland, Steve Donnelly and Johnny Nehme Humanitarian debate: Law, policy, action The use of nuclear weapons and human rights The human cost of nuclear weapons Stuart Casey-Maslen The development of the international initiative on the humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons and its effect on the nuclear weapons debate Alexander Kmentt Changing the discourse on nuclear weapons: The humanitarian initiative Elizabeth Minor Protecting humanity from the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons: Reframing the debate towards the humanitarian impact Richard Slade, Robert Tickner and Phoebe Wynn-Pope An African contribution to the nuclear weapons debate Sarah J. -

List of Participants 2019

List of participants Delegation Name Official function Algeria H.E. Mr Amar BELANI Ambassador extraordinary and plenipotentiary to the EU Australia Mr Tony Sheehan Deputy Secretary of Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade Austria H.E. Ms Karin Kneissl Federal Minister for Europe, Integration and Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Austria Bahrain H.E. Mr Bahiya Jawad ALJISHI Ambassador extraordinary and plenipotentiary to the EU Belgium H.E. Mr Didier Reynders Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Foreign, European Affairs and Defence of Belgium Bulgaria H.E. Ms Ekaterina Zaharieva Deputy Prime Minister for Judicial Reform and Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Bulgaria Canada Ms Pamela Goldsmith-Jones Parliamentary Secretary for the Minister of Foreign Affairs China H.E. Mr Xiaoyan XIE Special Envoy for Syria Issues of China Croatia Ms Ivana Živković Assistant Minister for Foreign and European Affairs of Croatia Cyprus Mr Andreas Kakouris Director of the Middle East and North Africa Directorate of the MFA Czech Republic H.E. Mr. Tomás Petříček Minister for Foreign Affairs of the Czech Republic Denmark H.E. Ms Ulla Tørnæs Minister for Development Affairs of Denmark Egypt H.E. Mr El Bakly Khaled Ambassador extraordinary and plenipotentiary to the EU Estonia H.E. Mr Rein Tammasaar Ambassador and Permanent Representative to the PSC European Bank Sir Suma CHAKRABARTI EBRD President for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) European Union Ms Federica Mogherini High Representative and Vice President European Union Mr Johannes Hahn Member of the European Commission European Union Mr Christos Stylianides Member of the European Commission Federative H.E. -

Mr. Peter Maurer

PETER MAURER President, International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Present & Future Challenges to Humanitarian Organisations Addressing the AIC Club, Peter Maurer, said the spirit of humanitarism lives on at the Red Cross, in spite of the many new challenges it faces. Founded 150 years ago, the Red Cross was founded by private citizens horrified by the sight of wounded soldiers left dying in the battlefields in Solferino. Peter Maurer reaffirmed that the organisations original principles and approaches remain valid 150 years later; neutrality, impartiality, independence from any religion or political affiliation. Peter Maurer, studied history and international law in Bern, Switzerland, where he was awarded a PhD. In, 1987, he entered the Swiss diplomatic service (Federal Department of Foreign Affairs). In 2004, Peter Maurer was appointed Ambassador and Permanent Representative of Switzerland to the United Nations in NY. He endeavoured to integrate Switzerland, which had only recently joined the UN, into its multilateral networks. In 2010, Peter Maurer became Switzerland’s State Secretary of Foreign Affairs, a position he held until being elected President of the ICRC. The ICRC remains a Swiss organisation, although worldwide, fewer than 30 percent of their staff are Swiss given a mandate by 193 countries to play a special humanitarian role. The past 150 years have seen a major transformation of the Red Cross from a charity into a professional humanitarian organisation. Its role of helping people affected by war is complicated by new developments, he said, that were not in the picture when the original Geneva Convention, setting rules for treatment of war victims were adopted in 1864. -

Economic and Social Council Humanitarian Affairs Segment 9 to 11 June 2020 Preceded by the Transition Event on 8 June Draft Programme (11 June)

Economic and Social Council Humanitarian Affairs Segment 9 to 11 June 2020 Preceded by the Transition Event on 8 June Draft Programme (11 June) On 16 March 2020, ECOSOC agreed (E/2020/L.4) that the theme for the 2020 ECOSOC Humanitarian Affairs Segment (HAS) will be “Reinforcing humanitarian assistance in the context of the 75th anniversary of the United Nations: taking action for people-centred solutions, strengthening effectiveness, respecting international humanitarian law and promoting the humanitarian principles”. The 2020 HAS will be held from 9 to 11 June in a fully virtual format. Since 1998, the Segment has been an essential platform for discussing issues related to strengthening the coordination and effectiveness of the humanitarian assistance of the United Nations, including assessing progress and identifying emerging issues, obstacles and challenges. It also promotes the sharing of experiences and lessons learned at the national and regional level. The organization of the 2020 HAS will include three interactive High-Level Panels, one High-Level Event and be complemented by side-events. On 8 June, the HAS will be preceded by the annual informal ECOSOC Event on the Transition from Relief to Development, which links discussions between the ECOSOC Operational Activities for Development Segment and the HAS. Side-events will also take place during the week. Day 1 - Monday 8 June 10:00 - 12:30 pm ECOSOC Event on the Transition from Relief to Development: The multidimensional and interconnected challenges in the Central Sahel region: reducing needs, risks and vulnerabilities for people through closer humanitarian, development and peacebuilding collaboration This event, convened jointly by the Chairs of the Operational Activity for Development Segment and the Humanitarian Affairs Segment, will consider some of the intersecting challenges facing the Central Sahel region, such as persistent and increasing insecurity, climate impacts, displacement, food insecurity, transhumance, and protection concerns. -

Principles Guiding Humanitarian Action National Societies Amelia B

Principles guiding 97 Number 897/8 Spring/Summer 2015 Volume humanitarian action Volume 97 Number 897/8 Spring/Summer 2015 Volume 97 Number 897/8 Spring/Summer 2015 Editorial: The humanitarian ethos in action Vincent Bernard, Editor-in-Chief The new Editorial Board of the International Review of the Red Cross Interview: Mr. Ma Qiang Former Executive Vice President of the Shanghai Branch of the Chinese Red Cross Humanitarian principles put to the test: Challenges to humanitarian action during decolonization Andrew Thompson Romancing principles and human rights: Are humanitarian principles salvageable? Stuart Gordon and Antonio Donini Unpacking the principle of humanity: Tensions and implications Larissa Fast Volunteers and responsibility for risk-taking: Changing interpretations of the Charter of Médecins Sans Frontières Caroline Abu Sa’Da and Xavier Crombé A matter of principle(s): The legal effect of impartiality and neutrality on States as humanitarian actors Kubo Macˇák Applying the humanitarian principles: Reflecting on the experience of the International Committee of the Red Cross Jérémie Labbé and Pascal Daudin Walking the walk: Evidence of Principles in Action from Red Cross and Red Crescent Principles guiding humanitarian action National Societies Amelia B. Kyazze Humanitarian debate: Law, policy, action Legislating against humanitarian principles: A case study on the humanitarian implications of Australian counterterrorism legislation Phoebe Wynn-Pope, Yvette Zegenhagen and Fauve Kurnadi From Fundamental Principles to individual action: Making the Principles come alive to promote a culture of non-violence and peace Katrien Beeckman Coming clean on neutrality and independence: The need to assess the application of humanitarian principles Ed Schenkenberg van Mierop Tools to do the job: The ICRC’s legal status, privileges and immunities Els Debuf Faith inspiration in a secular world: An Islamic perspective on humanitarian principles Lucy V. -

The Issue of Scale Considering the Large Number of National and International Staff in Need of Standardized Negotiation Capabilities?

High-Level Panel & Professional Roundtable Strengthehninge the Ciapsabilsitieus of Heumanitarian Organizations to Negotiate on the Frontlines 26 - 27 November 2019 Berlin, Germany I n p a r t n e r s h i p w i t h : 42 AADDVVAANNCCEEDD R REEGGIIOONNAALL W WOORRKKSSHHOOPP - - B BAANNGGKKOOKK 2 2001188 PEER WORKSHOP - COX'S BAZAR 2019 About the CCHN The Centre of Competence on Humanitarian Negotiation (CCHN) is a joint initiative of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the World Food Programme (WFP), Médecins sans Frontières (MSF- Switzerland) and the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD). It was launched in 2016 to facilitate the capture, analysis and sharing of negotiation experiences between humanitarian professionals. It provides a platform for both multi- and single-agency dialogue and intends to foster a community of practice among professionals engaged in humanitarian negotiations. The CCHN is staffed by seconded employees of the five Strategic Partners and operates out of Domaine "La Pastorale" at the heart of the international district of Geneva. During a five-year incubation phase, it is hosted by the ICRC. With the support of the five Strategic Partners, the CCHN organizes dedicated events, peer-to-peer exchanges and carries out research on issues identified by practitioners. A S t r a t e g i c P a r t n e r s h i p b e t w e e n : The Centre of Humanitarian Competence on Humanitarian Negotiation 106, Route de Ferney CH-1202 Geneva, Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] M o r e i n f o r m a t i o n : w w w . -

The Icrc's Operational Response to Covid-19

PRELIMINARY APPEAL THE ICRC’S OPERATIONAL RESPONSE TO COVID-19 PRELIMINARY APPEAL: THE ICRC’S OPERATIONAL RESPONSE TO COVID-19 2 MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT Dear Friends, Across the globe, we are all feeling the enormous impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. With the disease spreading rapidly, countries with weak health systems Where people will suffer the are likely to be under intense pressure, putting the lives of thousands of already vulnerable people in even deepest needs over the coming greater danger. weeks, the ICRC is already Many countries today are facing humanitarian emergencies or instability because of armed conflict there, acting to strengthen and violence and at the same time are challenged now with the spread of COVID-19. For those with resilience and prepare for limited capacity to respond to this urgent threat, the the worst. responsibility lies with the international community to step up its response. We must do so in a coordinated way, with actors playing to their strengths. But we can only do so with your support. The decisions we all make now will dictate the severity of global The ICRC will address the consequences of this crisis harm caused by COVID-19. Our appeal for 254 million by focusing on regions and communities in which it Swiss francs will allow us to respond to this crisis as it can have the most impact, working with vulnerable evolves, and to continue our other activities, many of people and in places that others are unable to access. which are enablers of the local responses to the crisis. -

CTA at 150 Panellist Profiles A5

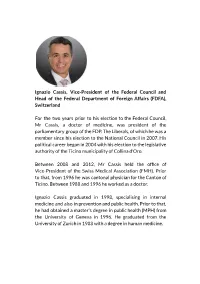

Ignazio Cassis, Vice-President of the Federal Council and Head of the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs (FDFA), Switzerland For the two years prior to his election to the Federal Council, Mr Cassis, a doctor of medicine, was president of the parliamentary group of the FDP. The Liberals, of which he was a member since his election to the National Council in 2007. His political career began in 2004 with his election to the legislative authority of the Ticino municipality of Collina d'Oro. Between 2008 and 2012, Mr Cassis held the office of Vice-President of the Swiss Medical Association (FMH). Prior to that, from 1996 he was cantonal physician for the Canton of Ticino. Between 1988 and 1996 he worked as a doctor. Ignazio Cassis graduated in 1998, specialising in internal medicine and also in prevention and public health. Prior to that, he had obtained a master's degree in public health (MPH) from the University of Geneva in 1996. He graduated from the University of Zurich in 1988 with a degree in human medicine. Peter Maurer, President, International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Peter Maurer is the President of the International Committee of the Red Cross (appointed in 2012). Under his leadership, the ICRC carries out humanitarian work in over 80 countries. As President, Mr Maurer has a unique exposure to today's main armed conflicts and the challenges of assisting and protecting people in need. He travels regularly to the major conflict theatres of the world including Syria, Iraq, Yemen, South Sudan and Myanmar. As the ICRC’s chief diplomat, and through the ICRC’s principled, neutral approach, Mr Maurer regularly meets with heads of states and other high-level officials as well as parties to conflict, to find solutions to pressing humanitarian concerns.