Fly Better Book Two 2Nd Edition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

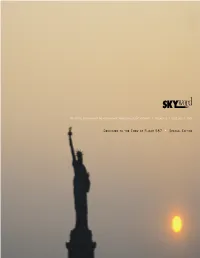

Flight Attendants • Volume Five • Issue One • 2002

the official publication of the association of professional flight attendants • volume five • issue one • 2002 Dedicated to the Crew of Flight 587 • Special Edition Death is nothing at all … I have only slipped away into the next room … I am I and you are you … what- ever we were to each other, that we are still. Call me by my old familiar name; speak to me in the easy way you always used. Put no difference into your tone; wear no forced air of solemnity or sorrow. Laugh as we always laughed at the little jokes we enjoyed together. Play, smile, think of me, pray for me. Let my name be ever the household word that it always was. Let it be spoken without effect, without the ghost of a shadow on it. Life means all that it ever meant. It is the same as it ever was; there is absolutely unbroken continuity. Why should I be out of mind because I am out of sight? I am but waiting for you for an interval somewhere very near just around the corner … all is well. – Canon Henry Scott Holland (1847 – 1918) 587 memorial issue special edition tableofcontents John Ward President Skyword Editorial Policy • Submissions to Skyword are due by Jeff Bott Vice President the first day of each month for publi- cation on the following month. The APFA reserves the right to edit any Linda Lanning Secretary submissions that are received for the purpose of publication in Skyword. Juan Johnson Treasurer Submissions will not be considered if they are too long, libelous, defamato- ry, not factual, in bad taste or are contractually incorrect. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

It's Girls in Aviation Day Orlando at #WAI17

The 28th Annual International Women in Aviation l Conference Saturday March 4 2017 TheSPONSORED BY ALASKADaily AIRLINES WAI: MEET YOUR FUTURE It’s Girls in Aviation Day Orlando at #WAI17 oday we welcome more than 200 girls from ages 8 to 17 to the Girls in Aviation Day Orlando—a fun and engaging program that is so well-regarded we are T full to capacity! We have local Girl Scouts attending who will earn their Aviation fun patch, and we would like to CHRISTOPHER MILLER CHRISTOPHER thank the Orange County Parks and Recreation department for conducting outreach in the local area to make the day a huge success. This program will present ideas beyond these girls’ wildest dreams. At Girls in Aviation Day Orlando, WAI engages students by facilitating state-of-the-art aviation workshops and activities. Here at the conference our young ladies will be connected with role models who will share their aviation careers through presentations, hands-on STEM learning op- portunities such as flying a simulator, learning to read charts, and trying out skills at an ATC tower, learn about robotics and unmanned vehicles plus learn to use tools that aircraft mechanics need in their careers. Girls will tour the exhibit hall where they will connect and engage with WAI members from all aspects of the aviation community. Older girls will meet with aerospace and aviation college representatives who will provide guidance on mapping their future to be career ready. As an extra special treat, the girls will be blown away by having lunch with Patty Wagstaff. -

Hispanic Heritage Month Storycorps

Digital Artifact Exploration for HISPANIC HERITAGE MONTH STORYCORPS This year, celebrate Latinx heritage by experiencing it. First, dig through a digital exhibit of artifacts Then, share your thoughts. Record a specially curated by our partners at the meaningful conversation on StoryCorps Hispanic Division and the American Folklife Connect, a remote recording platform, or Center of the Library of Congress. the StoryCorps App. Pick a single artifact or story to reflect on — or do them all. Be sure to add the keyword #LatinxHeritage2020 to Next, explore the StoryCorps Archive with your interview! ten stories from the Historias initiative, selected by StoryCorps facilitator Mia Raquel. What better way to celebrate? ARTIFACTS FROM THE HISPANIC DIVISION AND THE AMERICAN FOLKLIFE CENTER AT THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Latino Soccer, Chicago, Illinois George, Philip B, and Jonas Dovydenas. Latino soccer, Chicago, Illinois. Chicago Illinois, 1977. Chicago, Illinois. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/afc1981004.b52861/. n How has teamwork been a part of your life? Have you also been in a sports club or team that identifies as Latinx? n Reflect on how being part of a team or league like the one shown may impact your sense of identity and community. Did you learn more about your culture through these settings? What does a typical gathering entail? n Look at this photo in the series: What do you see? Do any of these items look familiar? n There are three games of soccer being played here, as well as a “paletero” selling ice cream. What are some examples of gatherings and community in your own life? STORYCORPS.ORG | COPYRIGHT © 2020, StoryCorps Inc. -

Unusual Attitudes and the Aerodynamics of Maneuvering Flight Author’S Note to Flightlab Students

Unusual Attitudes and the Aerodynamics of Maneuvering Flight Author’s Note to Flightlab Students The collection of documents assembled here, under the general title “Unusual Attitudes and the Aerodynamics of Maneuvering Flight,” covers a lot of ground. That’s because unusual-attitude training is the perfect occasion for aerodynamics training, and in turn depends on aerodynamics training for success. I don’t expect a pilot new to the subject to absorb everything here in one gulp. That’s not necessary; in fact, it would be beyond the call of duty for most—aspiring test pilots aside. But do give the contents a quick initial pass, if only to get the measure of what’s available and how it’s organized. Your flights will be more productive if you know where to go in the texts for additional background. Before we fly together, I suggest that you read the section called “Axes and Derivatives.” This will introduce you to the concept of the velocity vector and to the basic aircraft response modes. If you pick up a head of steam, go on to read “Two-Dimensional Aerodynamics.” This is mostly about how pressure patterns form over the surface of a wing during the generation of lift, and begins to suggest how changes in those patterns, visible to us through our wing tufts, affect control. If you catch any typos, or statements that you think are either unclear or simply preposterous, please let me know. Thanks. Bill Crawford ii Bill Crawford: WWW.FLIGHTLAB.NET Unusual Attitudes and the Aerodynamics of Maneuvering Flight © Flight Emergency & Advanced Maneuvers Training, Inc. -

Triple J Hottest 100 of the Decade Voting List: AZ Artists

triple j Hottest 100 of the Decade voting list: A-Z artists ARTIST SONG 360 Just Got Started {Ft. Pez} 360 Boys Like You {Ft. Gossling} 360 Killer 360 Throw It Away {Ft. Josh Pyke} 360 Child 360 Run Alone 360 Live It Up {Ft. Pez} 360 Price Of Fame {Ft. Gossling} #1 Dads So Soldier {Ft. Ainslie Wills} #1 Dads Two Weeks {triple j Like A Version 2015} 6LACK That Far A Day To Remember Right Back At It Again A Day To Remember Paranoia A Day To Remember Degenerates A$AP Ferg Shabba {Ft. A$AP Rocky} (2013) A$AP Rocky F**kin' Problems {Ft. Drake, 2 Chainz & Kendrick Lamar} A$AP Rocky L$D A$AP Rocky Everyday {Ft. Rod Stewart, Miguel & Mark Ronson} A$AP Rocky A$AP Forever {Ft. Moby/T.I./Kid Cudi} A$AP Rocky Babushka Boi A.B. Original January 26 {Ft. Dan Sultan} Dumb Things {Ft. Paul Kelly & Dan Sultan} {triple j Like A Version A.B. Original 2016} A.B. Original 2 Black 2 Strong Abbe May Karmageddon Abbe May Pony {triple j Like A Version 2013} Action Bronson Baby Blue {Ft. Chance The Rapper} Action Bronson, Mark Ronson & Dan Auerbach Standing In The Rain Active Child Hanging On Adele Rolling In The Deep (2010) Adrian Eagle A.O.K. Adrian Lux Teenage Crime Afrojack & Steve Aoki No Beef {Ft. Miss Palmer} Airling Wasted Pilots Alabama Shakes Hold On Alabama Shakes Hang Loose Alabama Shakes Don't Wanna Fight Alex Lahey You Don't Think You Like People Like Me Alex Lahey I Haven't Been Taking Care Of Myself Alex Lahey Every Day's The Weekend Alex Lahey Welcome To The Black Parade {triple j Like A Version 2019} Alex Lahey Don't Be So Hard On Yourself Alex The Astronaut Not Worth Hiding Alex The Astronaut Rockstar City triple j Hottest 100 of the Decade voting list: A-Z artists Alex the Astronaut Waste Of Time Alex the Astronaut Happy Song (Shed Mix) Alex Turner Feels Like We Only Go Backwards {triple j Like A Version 2014} Alexander Ebert Truth Ali Barter Girlie Bits Ali Barter Cigarette Alice Ivy Chasing Stars {Ft. -

Title Artist Gangnam Style Psy Thunderstruck AC /DC Crazy In

Title Artist Gangnam Style Psy Thunderstruck AC /DC Crazy In Love Beyonce BoomBoom Pow Black Eyed Peas Uptown Funk Bruno Mars Old Time Rock n Roll Bob Seger Forever Chris Brown All I do is win DJ Keo Im shipping up to Boston Dropkick Murphy Now that we found love Heavy D and the Boyz Bang Bang Jessie J, Ariana Grande and Nicki Manaj Let's get loud J Lo Celebration Kool and the gang Turn Down For What Lil Jon I'm Sexy & I Know It LMFAO Party rock anthem LMFAO Sugar Maroon 5 Animals Martin Garrix Stolen Dance Micky Chance Say Hey (I Love You) Michael Franti and Spearhead Lean On Major Lazer & DJ Snake This will be (an everlasting love) Natalie Cole OMI Cheerleader (Felix Jaehn Remix) Usher OMG Good Life One Republic Tonight is the night OUTASIGHT Don't Stop The Party Pitbull & TJR Time of Our Lives Pitbull and Ne-Yo Get The Party Started Pink Never Gonna give you up Rick Astley Watch Me Silento We Are Family Sister Sledge Bring Em Out T.I. I gotta feeling The Black Eyed Peas Glad you Came The Wanted Beautiful day U2 Viva la vida Coldplay Friends in low places Garth Brooks One more time Daft Punk We found Love Rihanna Where have you been Rihanna Let's go Calvin Harris ft Ne-yo Shut Up And Dance Walk The Moon Blame Calvin Harris Feat John Newman Rather Be Clean Bandit Feat Jess Glynne All About That Bass Megan Trainor Dear Future Husband Megan Trainor Happy Pharrel Williams Can't Feel My Face The Weeknd Work Rihanna My House Flo-Rida Adventure Of A Lifetime Coldplay Cake By The Ocean DNCE Real Love Clean Bandit & Jess Glynne Be Right There Diplo & Sleepy Tom Where Are You Now Justin Bieber & Jack Ü Walking On A Dream Empire Of The Sun Renegades X Ambassadors Hotline Bling Drake Summer Calvin Harris Feel So Close Calvin Harris Love Never Felt So Good Michael Jackson & Justin Timberlake Counting Stars One Republic Can’t Hold Us Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Ft. -

Star Channels, September 23-29

SEPTEMBER 23-29, 2018 staradvertiser.com MAGNUM .0 2 Private investigator Thomas Magnum returns to TV screens on Monday, Sept. 24, when CBS doubles down on the reboot trend and reintroduces another fondly remembered franchise of yore with Magnum P.I. Jay Hernandez takes on the titular role in the reboot, while the character of Higgins is now female, played by Welsh actress Perdita Weeks. Premiering Monday, Sept. 24, on CBS. WE’RE LOOKING FOR PEOPLE WHO HAVE SOMETHING TO SAY. Are you passionate about an issue? An event? A cause? ¶ũe^eh\Zga^eirhn[^a^Zk][r^fihp^kbg`rhnpbmama^mkZbgbg`%^jnbif^gm olelo.org Zg]Zbkmbf^rhng^^]mh`^mlmZkm^]'Begin now at olelo.org. ON THE COVER | MAGNUM P.I. Back to the well ‘Magnum P.I.’ returns to the show was dropped in May. The person that the show wasn’t interested in being a 1:1 behind the controls is Peter M. Lenkov, a self- remake of its predecessor and was willing to television with CBS reboot professed fan of the ‘80s “Magnum” and a take big, potentially clumsy risks that could at- writer/producer on CBS’s first Hawaiian crime- tract the ire of diehard Magnum-heads. By Kenneth Andeel fest reboot, “Hawaii Five-0.” Lenkov’s secret Magnum’s second most essential posses- TV Media weapon for the pilot was director Justin Lin. Lin sion (after the mustache) was his red Ferrari, is best known for thrilling audiences with his and it turns out that that ride wasn’t so sacred, ame the most famous mustache to ever dynamic and outrageous action sequences in either. -

Star Channels, March 21

staradvertiser.com MARCH 21 - 27, 2021 FAMILY MATTERS Now that the kids are a bit older, Paul (Martin Freeman) and Ally (Daisy Haggard) face new parenting challenges in Season 2 of Breeders. This season, 13-year-old Luke (Alex Eastwood) struggles with increasing anxiety, while 10-year-old Ava (Eve Prenelle) is growing more independent. Premiering Monday, March 22, on FX. Enjoy original songs performed by up and coming local artists. Hosted by Jake ShimabukuroZg]Ûef^]Zm¶ũe^ehl Mele A‘e new soundstage, Studio 1122. A SHOWCASE FOR HAWAI¶I’S SUNDAY, MARCH 28, 7PM olelo.org olelo.org ASPIRING ARTISTS CHANNEL 53 | olelo.org/53 590242_MeleAePremiere_2_withJake_F.indd 1 3/3/21 3:19 PM ON THE COVER | BREEDERS Father doesn’t know best Martin Freeman’s of the show’s creators. The actor claims he had about “the parental paradox that you’d happily been inspired to create the show after having die for your children but quite often also want to ‘Breeders’ returns to FX a dream about yelling at his children. He ex- kill them.” In the first season, Paul and Ally dealt plained the premise in an interview with Variety with the very real pressures of modern-day par- By Kyla Brewer when the first season of “Breeders” premiered enting while trying to stay connected romanti- TV Media in March 2020. cally, work full time and maintain their sanity, “It doesn’t tip over into being actually trau- which, as just about any parent can attest, is no n the early days of television, TV dads always matic, but it should ring bells as far as the small feat. -

Downloading, and Skydiving, Cameraflyers Packing, Dirt-Diving, Teams Had - Do to Everyone a Job Where Place Exciting an Into Trophies for the Winners

SHAPED TOP AND BOTTOM PANELS FOR SMOOTHEST AIRFOIL SMALLEST PACK VOLUME COLOUR-CODED LINE ATTACHMENTS FOR EASE OF PRO-PACKING UGHTEST TOGGLE PRESSURE PISA For more information about the Heat Wave canopy, contact: Thomas Sports Equipment Ltd; Pinfold Lane, w m Industrial Estate, Bridlington, East Yorkshire - Y01 B 5XS Telephone (01262] 6 7 8 2 9 9 Fax (01262) 6020B3 CONTENTS AUGUST 1997 P A R / X C H U T t S T Journal of the British Parachute Association FEATURES WHO TO CONTACT: 16-way Goes Official . ___ 6 E D IT O R IA L: To submit an article or photograph contact: Southern Regionals . ___ 9 Lesley Gale Sport Parachutist New Age Nationals . .17 3 Burton Street,Peterborough PE1 5HA Scottish Nationals . .21 Tel/Fax: 01733 755 860 e-mail: sportpara@ aol.com 100-way Jewel . .24 ADVERTISING: Dual Square Report . .33 To enquire about advertising see pages 47/8 or contact: Classics Update . .36 Scott Dougal Pagefast Ltd 4-5 Lansil Way, Lancaster LA1 3QY REGULARS Tel: 01524 841 010 Fax: 01524 841 578 e-mail: 101626.2656@ compuserve.com Diary . ___ 2 Events . ___ 3 To subscribe to Sport Parachutist magazine fill out the coupon on page 48 News.. ___4 ©SPORT PARACHUTIST Council Matters . ___ 5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a The Word on the Street . .10 retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the permission of Kit News .. .12 the Editor. The views expressed in Sport Parachutist are those of the contributors and Dive of the Month . -

The Flying Adventures of the Puertoricoflyers

The Flying Adventures of the PuertoRicoFlyers By: Galin Hernandez Millie Santiago The Flying Adventures of the PuertoRicoFlyers Chapter 1 ….2008 Jazmynn Trip Chapter 2…..2008 Christmas to Roatan Chapter 3..…2009 Thanksgiving to Panama Chapter 4….2010 Puerto Rico Fly In Chapter 5……2011 Puerto Rico Holiday Trip Chapter 6……2012 Almost Trip Chapter 7……2013 4th Annual Caribbean Trip Chapter 8……2014 Return to El Salvador Written by: Galin Hernandez Photos by: Milagros Santiago Page 1 Jazmynn Trip Chapter 1 (Pre-Flight) ...................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter 2 (Off I go, to Cozumel) ..................................................................................................... 7 Chapter 3 (Cozumel to Key West) ................................................................................................. 11 Chapter 4 (Cheap Fuel and Grumpy ATC) .................................................................................... 15 Chapter 5 (Family, Friends, Fixing and Flying) ............................................................................ 19 Chapter 6 (Bad Weather and Bad Comms) .................................................................................... 25 Chapter 7 (Clearwater to Cancun via Marathon Key) ................................................................... 29 Chapter 8 (All the way home) ........................................................................................................ 35 ABBREVIATIONS