Oveta Culp Hobby: a Study of Power and Control Robert T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fellows of the American Bar Foundation

THE FELLOWS OF THE AMERICAN BAR FOUNDATION 2015-2016 2015-2016 Fellows Officers: Chair Hon. Cara Lee T. Neville (Ret.) Chair – Elect Michael H. Byowitz Secretary Rew R. Goodenow Immediate Past Chair Kathleen J. Hopkins The Fellows is an honorary organization of attorneys, judges and law professors whose pro- fessional, public and private careers have demonstrated outstanding dedication to the welfare of their communities and to the highest principles of the legal profession. Established in 1955, The Fellows encourage and support the research program of the American Bar Foundation. The American Bar Foundation works to advance justice through ground-breaking, independ- ent research on law, legal institutions, and legal processes. Current research covers meaning- ful topics including legal needs of ordinary Americans and how justice gaps can be filled; the changing nature of legal careers and opportunities for more diversity within the profession; social and political costs of mass incarceration; how juries actually decide cases; the ability of China’s criminal defense lawyers to protect basic legal freedoms; and, how to better prepare for end of life decision-making. With the generous support of those listed on the pages that follow, the American Bar Founda- tion is able to truly impact the very foundation of democracy and the future of our global soci- ety. The Fellows of the American Bar Foundation 750 N. Lake Shore Drive, 4th Floor Chicago, IL 60611-4403 (800) 292-5065 Fax: (312) 564-8910 [email protected] www.americanbarfoundation.org/fellows OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS OF THE Rew R. Goodenow, Secretary AMERICAN BAR FOUNDATION Parsons Behle & Latimer David A. -

Bud Fisher—Pioneer Dean of the Comic Artists

Syracuse University SURFACE The Courier Libraries Winter 1979 Bud Fisher—Pioneer Dean of the Comic Artists Ray Thompson Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, and the American Popular Culture Commons Recommended Citation Thompson, Ray. "Bud Fisher—Pioneer Dean of the Comic Artists." The Courier 16.3 and 16.4 (1979): 23-36. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ISSN 0011-0418 ARCHIMEDES RUSSELL, 1840 - 1915 from Memorial History ofSyracuse, New York, From Its Settlement to the Present Time, by Dwight H. Bruce, Published in Syracuse, New York, by H.P. Smith, 1891. THE COURIER SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES Volume XVI, Numbers 3 and 4, Winter 1979 Table of Contents Winter 1979 Page Archimedes Russell and Nineteenth-Century Syracuse 3 by Evamaria Hardin Bud Fisher-Pioneer Dean of the Comic Artists 23 by Ray Thompson News of the Library and Library Associates 37 Bud Fisher - Pioneer Dean of the Comic Artists by Ray Thompson The George Arents Research Library for Special Collections at Syracuse University has an extensive collection of original drawings by American cartoonists. Among the most famous of these are Bud Fisher's "Mutt and Jeff." Harry Conway (Bud) Fisher had the distinction of producing the coun try's first successful daily comic strip. Comics had been appearing in the press of America ever since the introduction of Richard F. -

Woman War Correspondent,” 1846-1945

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository CONDITIONS OF ACCEPTANCE: THE UNITED STATES MILITARY, THE PRESS, AND THE “WOMAN WAR CORRESPONDENT,” 1846-1945 Carolyn M. Edy A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved by: Jean Folkerts W. Fitzhugh Brundage Jacquelyn Dowd Hall Frank E. Fee, Jr. Barbara Friedman ©2012 Carolyn Martindale Edy ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract CAROLYN M. EDY: Conditions of Acceptance: The United States Military, the Press, and the “Woman War Correspondent,” 1846-1945 (Under the direction of Jean Folkerts) This dissertation chronicles the history of American women who worked as war correspondents through the end of World War II, demonstrating the ways the military, the press, and women themselves constructed categories for war reporting that promoted and prevented women’s access to war: the “war correspondent,” who covered war-related news, and the “woman war correspondent,” who covered the woman’s angle of war. As the first study to examine these concepts, from their emergence in the press through their use in military directives, this dissertation relies upon a variety of sources to consider the roles and influences, not only of the women who worked as war correspondents but of the individuals and institutions surrounding their work. Nineteenth and early 20th century newspapers continually featured the woman war correspondent—often as the first or only of her kind, even as they wrote about more than sixty such women by 1914. -

Lady Bird Johnson STAAR 4, 7 - Writing - 1, 2, 3 • from the Texas Almanac 2010–2011 4, 7, 8 - Reading - 1, 2, 3 8 - Social Studies - 2 Instructional Suggestions

SPECIAL LESSON 9 SOCIAL STUDIES TEKS 4 - 4, 6, 21, 22, 23 TEXAS ALMANAC TEACHERS GUIDE 7 - 9, 21, 22, 23 8 - 23 Lady Bird Johnson STAAR 4, 7 - Writing - 1, 2, 3 • From the Texas Almanac 2010–2011 4, 7, 8 - Reading - 1, 2, 3 8 - Social Studies - 2 INSTRUCTIONAL SUGGESTIONS 1. PEN PAL PREPARATION: Students will read the article “Lady Bird Johnson” in the Texas Almanac 2010–2011 or the online article: http://www.texasalmanac.com/topics/history/lady-bird-johnson They will then answer the questions on the Student Activity Sheet and compose an email to a pen pal in another country explaining how Claudia Alta “Lady Bird” Taylor Johnson became a beloved Texas icon. 2. TIMELINE: After reading the article “Lady Bird Johnson,” students will create an annotated, illustrated, and colored timeline of Lady Bird Johnson’s life. Use 15 of the dates found in the article or in the timeline that accompanies the article in the Texas Almanac 2010–2011. 3. ESSAY: Students will write a short essay that discusses one of the two points listed, below: a. Explain how Lady Bird’s experiences influenced her life before she married Lyndon Baines Johnson. b. Describe and analyze Lady Bird’s influence on the environment after her marriage to Johnson. Students may use one of the lined Student Activity Sheets for this activity. 4. SIX-PANEL CARTOON: Students will create and color a six-panel cartoon depicting Lady Bird’s influence on the environment after her marriage to LBJ. 5. POEM, SONG, OR RAP: Students will create a poem, song, or rap describing Lady Bird Johnson’s life. -

CONFERENCE RECEPTION New Braunfels Civic Convention Center

U A L Advisory Committee 5 31 rsdt A N N E. RAY COVEY, Conference Chair AEP Texas PATRICK ROSE, Conference Vice Chair Corridor Title Former Texas State Representative Friday, March 22, 2019 KYLE BIEDERMANN – Texas State CONFERENCE RECEPTION Representative 7:45 - 8:35AM REGISTRATION AND BREAKFAST MICHAEL CAIN Heavy Hors d’oeuvres • Entertainment Oncor 8:35AM OPENING SESSION DONNA CAMPBELL – State Senator 7:00 pm, Thursday – March 21, 2019 TAL R. CENTERS, JR., Regional Vice Presiding: E. Ray Covey – Advisory Committee Chair President– Texas New Braunfels Civic Convention Center Edmund Kuempel Public Service Scholarship Awards CenterPoint Energy Presenter: State Representative John Kuempel JASON CHESSER Sponsored by: Wells Fargo Bank CPS Energy • Guadalupe Valley Electric Cooperative (GVEC) KATHLEEN GARCIA Martin Marietta • RINCO of Texas, Inc. • Rocky Hill Equipment Rentals 8:55AM CHANGING DEMOGRAPHICS OF TEXAS CPS Energy Alamo Area Council of Governments (AACOG) Moderator: Ray Perryman, The Perryman Group BO GILBERT – Texas Government Relations USAA Panelists: State Representative Donna Howard Former Recipients of the ROBERT HOWDEN Dan McCoy, MD, President – Blue Cross Blue Shield of Texas Texans for Economic Progress Texan of the Year Award Steve Murdock, Former Director – U.S. Census Bureau JOHN KUEMPEL – Texas State Representative Pia Orrenius, Economist – Dallas Federal Reserve Bank DAN MCCOY, MD, President Robert Calvert 1974 James E. “Pete” Laney 1996 Blue Cross Blue Shield of Texas Leon Jaworski 1975 Kay Bailey Hutchison 1997 KEVIN MEIER Lady Bird Johnson 1976 George Christian 1998 9:50AM PROPERTY TAXES AND SCHOOL FINANCE Texas Water Supply Company Dolph Briscoe 1977 Max Sherman 1999 Moderator: Ross Ramsey, Co-Founder & Exec. -

Hispanic Archival Collections Houston Metropolitan Research Cent

Hispanic Archival Collections People Please note that not all of our Finding Aids are available online. If you would like to know about an inventory for a specific collection please call or visit the Texas Room of the Julia Ideson Building. In addition, many of our collections have a related oral history from the donor or subject of the collection. Many of these are available online via our Houston Area Digital Archive website. MSS 009 Hector Garcia Collection Hector Garcia was executive director of the Catholic Council on Community Relations, Diocese of Galveston-Houston, and an officer of Harris County PASO. The Harris County chapter of the Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations (PASO) was formed in October 1961. Its purpose was to advocate on behalf of Mexican Americans. Its political activities included letter-writing campaigns, poll tax drives, bumper sticker brigades, telephone banks, and community get-out-the- vote rallies. PASO endorsed candidates supportive of Mexican American concerns. It took up issues of concern to Mexican Americans. It also advocated on behalf of Mexican Americans seeking jobs, and for Mexican American owned businesses. PASO produced such Mexican American political leaders as Leonel Castillo and Ben. T. Reyes. Hector Garcia was a member of PASO and its executive secretary of the Office of Community Relations. In the late 1970's, he was Executive Director of the Catholic Council on Community Relations for the Diocese of Galveston-Houston. The collection contains some materials related to some of his other interests outside of PASO including reports, correspondence, clippings about discrimination and the advancement of Mexican American; correspondence and notices of meetings and activities of PASO (Political Association of Spanish-Speaking Organizations of Harris County. -

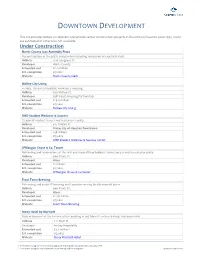

Downtown Development Project List

DOWNTOWN DEVELOPMENT This list provides details on all public and private sector construction projects in Downtown Houston since 1995. Costs are estimated or otherwise not available. Under Construction Harris County Jury Assembly Plaza Reconstruction of the plaza and pavilion including relocation of electrical vault. Address 1210 Congress St. Developer Harris County Estimated cost $11.3 million Est. completion 3Q 2021 Website Harris County Clerk McKee City Living 4‐story, 120‐unit affordable‐workforce housing. Address 626 McKee St. Developer Gulf Coast Housing Partnership Estimated cost $29.9 million Est. completion 4Q 2021 Website McKee City Living UHD Student Wellness & Success 72,000 SF student fitness and recreation facility. Address 315 N Main St. Developer University of Houston Downtown Estimated cost $38 million Est. completion 2Q 2022 Website UHD Student Wellness & Success Center JPMorgan Chase & Co. Tower Reframing and renovations of the first and second floor lobbies, tunnel access and the exterior plaza. Address 600 Travis St. Developer Hines Estimated cost $2 million Est. completion 3Q 2021 Website JPMorgan Chase & Co Tower Frost Town Brewing Reframing and 9,100 SF brewing and taproom serving locally inspired beers Address 600 Travis St. Developer Hines Estimated cost $2.58 million Est. completion 3Q 2021 Website Frost Town Brewing Moxy Hotel by Marriott Redevelopment of the historic office building at 412 Main St. into a 13‐story, 119‐room hotel. Address 412 Main St. Developer InnJoy Hospitality Estimated cost $4.4 million P Est. completion 2Q 2022 Website Moxy Marriott Hotel V = Estimated using the Harris County Appriasal Distict public valuation data, January 2019 P = Estimated using the City of Houston's permitting and licensing data Updated 07/01/2021 Harris County Criminal Justice Center Improvement and flood damage mitigation of the basement and first floor. -

Cassociation^ of Southern Women for the "Prevention of Cynching ******

cAssociation^ of Southern Women for the "Prevention of Cynching JESSIE DANIEL AMES, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR MRS. ATTWOOD MARTIN MRS. W. A. NEWELL CHAIRMAN 703 STANDARD BUILDING SECRETARY-TREASURER Louisville, Ky. Greensboro, n. c. EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE cAtlanta, Qa MRS. J. R. CAIN, COLUMBIA, S. C. MRS. GEORGE DAVIS, ORANGEBURG, S. C. MRS. M. E. TILLY, ATLANTA, GA. MRS. W. A. TURNER, ATLANTA, GA. MRS. E. MARVIN UNDERWOOD, ATLANTA, GA. January 7, 1932 Composite Picture of Lynching and Lynchers "Vuithout exception, every lynching is an exhibition of cowardice and cruelty. 11 Atlanta Constitution, January 16, 1931. "The falsity of the lynchers' pretense that he is the guardian of chastity." Macon News, November 14, 1930. "The lyncher is in very truth the most vicious debaucher of spirit ual values." Birmingham Age Herald, November 14, 1930. "Certainly th: atrocious barbarities of the mob do not enhance the security of women." Charleston, S. C. Evening lost. "Hunt down a member of a lynching mob and he will usually be found hiding behind a woman's skirt." Christian Century, January 8, 1931. ****** In the year 1930, Texas and Georgia, were black spots on the map. This year, 1931, those two states cleaned up and came thro with "no lynchings." But honors arc even. Two states, Louisiana and Tennessee, with "no lynchings" in 1930, add one each in 1931. Florida and Mississippi were the only two states having lynchings in both years. Five of the eight in the South were in these two States alone. Jessie Daniel limes Executive Director Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching CENTRAL COUNCIL Representatives at Large Mrs. -

Flight Attendants • Volume Five • Issue One • 2002

the official publication of the association of professional flight attendants • volume five • issue one • 2002 Dedicated to the Crew of Flight 587 • Special Edition Death is nothing at all … I have only slipped away into the next room … I am I and you are you … what- ever we were to each other, that we are still. Call me by my old familiar name; speak to me in the easy way you always used. Put no difference into your tone; wear no forced air of solemnity or sorrow. Laugh as we always laughed at the little jokes we enjoyed together. Play, smile, think of me, pray for me. Let my name be ever the household word that it always was. Let it be spoken without effect, without the ghost of a shadow on it. Life means all that it ever meant. It is the same as it ever was; there is absolutely unbroken continuity. Why should I be out of mind because I am out of sight? I am but waiting for you for an interval somewhere very near just around the corner … all is well. – Canon Henry Scott Holland (1847 – 1918) 587 memorial issue special edition tableofcontents John Ward President Skyword Editorial Policy • Submissions to Skyword are due by Jeff Bott Vice President the first day of each month for publi- cation on the following month. The APFA reserves the right to edit any Linda Lanning Secretary submissions that are received for the purpose of publication in Skyword. Juan Johnson Treasurer Submissions will not be considered if they are too long, libelous, defamato- ry, not factual, in bad taste or are contractually incorrect. -

~/ \ I Te#R *Tate *F Erjuts LLOYD DOGGETT STATE SENATOR 406 West 13Th Street Austin, Texas 78701 512/477-7080

·~»Els,/4/ ' E*r *rnate af *y~/ \ i tE#r *tate *F Erjuts LLOYD DOGGETT STATE SENATOR 406 West 13th Street Austin, Texas 78701 512/477-7080 October 6, 1984 Just thought you would be interested in a copy of the press release announcing formation of the Policy Advisory Council of which you are a member. Sincerely, Ll*d Doggett Pol. Adv. Pd. for by Lloyd Doggett Campaign Fund, 406 W. 13th St., Austin, TX 78701 c:~ . news from Lloyd ~Y=rs; Austin, Texas 78701 Sen.Doggett 512/477-7080 democrat for U.S. Senate Thursday, October 4, 1984 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: BILL COLLIER OR MARK MCKINNON (512) 482-0867 DOGGETT POLICY ADVISORY COUNCIL CHAIRED BY GRONOUSKI, JORDAN AUSTIN -- Senator Lloyd Doggett, Democratic nominee for the U.S. Senate, today released the membership.of his Policy Advisory Council, which is co-chaired by John A. Gronouski, professor and former dean of the LBJ School of Public Affairs, and former Congresswoman Barbara Jordan, holder of the LBJ Centennial Chair in National Policy at the LBJ School. "The Council includes some of the greatest minds in our state and symbolizes a commitment to excellence that is the hallmark of the Texas approach to public policy," Doggett said. "I truly appreciate the initiative Barbara Jordan and John Gronouski have taken in assembling this group. Among its members are my most trusted friends and advisers on issues of concern to all Texans. They are the people who advise me now and will continue to advise me in the U.S. Senate.w The Doggett Policy Advisory Council includes three former Presidential Cabinet secretaries; four former ambassadors; a Nobel Prize winner; the head of one of the largest companies in America, U.S. -

"Lady Bird" Johnson Interview XXXII

LYNDON BAINES JOHNSON LIBRARY ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION LBJ Library 2313 Red River Street Austin, Texas 78705 http://www.lbjlib.utexas.edu/johnson/archives.hom/biopage.asp CLAUDIA "LADY BIRD" JOHNSON ORAL HISTORY, INTERVIEW XXXII PREFERRED CITATION For Internet Copy: Transcript, Claudia "Lady Bird" Johnson Oral History Interview XXXII, 8/3-4/82, by Michael L. Gillette, Internet Copy, LBJ Library. For Electronic Copy on Compact Disc from the LBJ Library: Transcript, Claudia "Lady Bird" Johnson Oral History Interview XXXII, 8/3-4/82, by Michael L. Gillette, Electronic Copy, LBJ Library. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION LYNDON BAINES JOHNSON LIBRARY Legal Agreement Pertaining to the Oral History Interviews of CLAUDIA TAYLOR JOHNSON In accordance with the provisions of Chapter 21 of Title 44, United States Code, I, Claudia Taylor Johnson of Austin, Texas, do hereby give, donate and convey to the United States of America all my rights, title and interest in the tape recordings and transcripts of the personal interviews conducted with me and prepared for deposit in the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library. A list of the interviews is attached. This assignment is subject to the following terms and conditions: (1) The transcripts shall be available to all researchers. (2) The tape recordings shall be available to all researchers. (3) I hereby assign to the United States Government all copyright I may have in the interview transcripts and tapes. (4) Copies of the transcripts and tape recordings may be provided by the library to researchers upon request. (5) Copies of the transcripts and tape recordings may be deposited in or loaned to other institutions. -

ABSTRACT “The Good Angel of Practical Fraternity:” the Ku Klux Klan in Mclennan County, 1915-1924. Richard H. Fair, M.A. Me

ABSTRACT “The Good Angel of Practical Fraternity:” The Ku Klux Klan in McLennan County, 1915-1924. Richard H. Fair, M.A. Mentor: T. Michael Parrish, Ph.D. This thesis examines the culture of McLennan County surrounding the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s and its influence in central Texas. The pervasive violent nature of the area, specifically cases of lynching, allowed the Klan to return. Championing the ideals of the Reconstruction era Klan and the “Lost Cause” mentality of the Confederacy, the 1920s Klan incorporated a Protestant religious fundamentalism into their principles, along with nationalism and white supremacy. After gaining influence in McLennan County, Klansmen began participating in politics to further advance their interests. The disastrous 1922 Waco Agreement, concerning the election of a Texas Senator, and Felix D. Robertson’s gubernatorial campaign in 1924 represent the Klan’s first and last attempts to manipulate politics. These failed endeavors marked the Klan’s decline in McLennan County and Texas at large. “The Good Angel of Practical Fraternity:” The Ku Klux Klan in McLennan County, 1915-1924 by Richard H. Fair, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of History ___________________________________ Jeffrey S. Hamilton, Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ T. Michael Parrish, Ph.D., Chairperson ___________________________________ Thomas L. Charlton, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Stephen M. Sloan, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Jerold L. Waltman, Ph.D. Accepted by the Graduate School August 2009 ___________________________________ J.