The Pitfalls of Poor Psychometric Properties : a Rejoinder to Hofstede's Reply to Us

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pathways to the University of Waikato

Pathways to the University of Waikato 2020 pathways.waikato.ac.nz Courses at Waikato Pathways College are delivered by Study Group NZ Limited on behalf of the University of Waikato Welcome to Waikato Welcome to the University of Waikato, located in Hamilton, New Zealand. The University is truly world-class, ranked 266 in the world.* Experience smaller class sizes, accessible staff, and a welcoming and diverse student community. Students first Pathway Student Visa Flexible degree structures allow you to follow your A Pathway Student Visa may be granted for up to a interests and career plans. The University’s emphasis maximum of five years and allows you to undertake up on practical experiences means you will be ready to to three consecutive programmes of study on a single go from the classroom into a successful career. student visa. For more information visit immigration.govt.nz Bridging the gap to university Quality assurance Waikato Pathways College offers a variety of courses The University of Waikato took part in the Cycle 5 which will help you progress to the University degree Academic Audit in association with the Academic Quality of your choice. Agency for New Zealand Universities (AQA) and received an audit report in 2015. The Cycle 6 Academic Audit is University pathways and English ongoing. Details are available at waikato.ac.nz/official- Language Programmes info/academic-audit/ Our university pathways and English Language programme give you all the tools you need to continue your study at degree level. Students who pass their programme are guaranteed entry to most degrees at the University. -

The University of Waikato Te Whare Wānanga O Waikato

THE UNIVERSITY OF WAIKATO TE WHARE WĀNANGA O WAIKATO ACADEMIC BOARD: 27 February 2013 Minutes of the meeting held on Wednesday 27 February 2013 Present: Professor R Crawford (Chair), Mr L Arthur, Professor N Boister, Professor K Broughan, Dr A Campbell, Professor B Clarkson, Professor R Coll, Ms B Cooper, Associate Professor W Drewery, Professor A Gillespie, Professor B Grant, Mr R Hallett, Professor D Hodgetts, Professor G Holmes, Dr D Johnson, Professor A Jones, Associate Professor S Jones, Professor P Kamp, Dr A Kingsbury, Mr R Kyle, Mr A Letcher, Dr D Lumsden, Ms S Morrison, Professor B Morse, Ms S Nock, Professor D Penney, Professor F Scrimgeour, Associate Professor J Tressler, Professor K Weaver, Professor E Weymes, Professor M Wilson and Dr A Zahra Secretariat: Ms M Jordan-Tong and Ms R Boyer-Willisson In Attendance: Mrs A Drake and Ms H Pridmore 13.01 APOLOGIES Received Apologies for absence from Professor B Barton, Ms C Blickem, Dr T Bowell, Dr K Bryan, Dr A Hinze, Professor R Moltzen, Associate Professor K Pavlovich and Professor L Smith. 13.02 CONFIRMATION OF THE MINUTES OF THE MEETING HELD ON 20 NOVEMBER 2012 Confirmed The minutes of the meeting held on 20 November 2013 as set out in document 13/64a, subject to the correction of Dr David Lumsden’s title in the list of members present. 13.03 EXECUTIVE APPROVAL Reported That the following items had been approved executively by the Chair of the Academic Board between the 20 November 2012 and 27 February 2013 meetings: 1. Category C Proposals The Category C proposals as set out in the following documents: a. -

Parents' Information Guide

Parents’ Information Guide 2021 02 The University of Waikato How do I know the University of Waikato is the right choice for my whānau? University is an exciting chapter in any student’s life and, as a parent or caregiver you play a key role in advising and supporting your child during this time. We aim to make the transition to either of our campuses, as well as a range university as smooth as possible for not of support services to help your child only our students, but for you as well. achieve their best success with us. So, this guide has been designed with We also provide a number of activities you in mind. We hope it gives you the to bring your whānau on to campus. confidence to know that the University of Campus and hostel tours and community Waikato will take great care of your child days like Kīngitanga are a great way to while also continuing to advise, support, get a taste of what studying with Waikato educate and challenge them. will be like, so why not pay us a visit? While academic success is our mainstay, We also welcome you to get in touch we understand that there is a lot more at any time should you have any to the university experience than just an questions or concerns by calling us outstanding education. on 0800 WAIKATO or emailing [email protected]. We offer plenty of opportunities for our students to make the most of their Visit waikato.ac.nz/go/parents to find university experience and to settle in on out more. -

Table of Contents 1 7 35 79 99

TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction James Beattie 1 Political agitation for forest conservation: Victoria, 1860–1960 Stephen Legg 7 Wartime political ambition behind one image of a dam in Australia is Developing a Dust Bowl (1943): US/Australian film imagery, environment, and nationalist storytelling Janette-Susan Bailey 35 New perspectives on methodology in garden history: Approaches towards writing about imported medicinal plants in colonial New Zealand Joanna Bishop 79 The Tuntian system in Xinjiang under the Qing Dynasty: A perspective from environmental history Ts’ui-jung Liu and I-chun Fan 99 Epizootics and the colonial legacies of the United States in Philippine veterinary science Arleigh Ross D. Dela Cruz 143 International Review of Environmental History is published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is available online at press.anu.edu.au ISSN 2205-3204 (print) ISSN 2205-3212 (online) Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover image: Dorothea Lange, Abandoned Dust Bowl Home. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program. © 2016 ANU Press Editor: James Beattie, History, University of Waikato & Research Associate, Centre for Environmental History, The Australian National University Associate Editor: Brett M. Bennett, Western Sydney University Editorial Board: • Maohong Bao包茂宏, Peking University • Nancy Jacobs, Brown University • Greg Barton, Western Sydney University • Ryan Tucker Jones, University of Auckland • Tom Brooking, University of Otago -

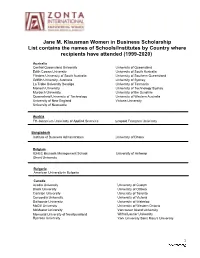

2020 JMK Schools

Jane M. Klausman Women in Business Scholarship List contains the names of Schools/Institutes by Country where recipients have attended (1999-2020) Australia Central Queensland University University of Queensland Edith Cowan University University of South Australia Flinders University of South Australia University of Southern Queensland Griffith University, Australia University of Sydney La Trobe University Bendigo University of Tasmania Monash University University of Technology Sydney Murdoch University University of the Sunshire Queensland University of Technology University of Western Australia University of New England Victoria University University of Newcastle Austria FH-Joanneum University of Applied Sciences Leopold Franzens University Bangladesh Institute of Business Administration University of Dhaka Belgium ICHEC Brussels Management School University of Antwerp Ghent University Bulgaria American University in Bulgaria Canada Acadia University University of Guelph Brock University University of Ottawa Carleton University University of Toronto Concordia University University of Victoria Dalhousie University University of Waterloo McGill University University of Western Ontario McMaster University Vancouver Island University Memorial University of Newfoundland Wilfrid Laurier University Ryerson University York University Saint Mary's University 1 Chile Adolfo Ibanez University University of Santiago Chile University of Chile Universidad Tecnica Federico Santa Maria Denmark Copenhagen Business School Technical University of Denmark -

University of Waikato Study Abroad & Exchange Guide

Study Abroad & Exchange Guide Why New Zealand? New Zealand is a small yet mighty country located in the various aspects of New Zealand life. At the airport, spot South Pacific; our closest neighbours include Australia Māori translations on signage, and during your travels and Fiji. Our claims to fame include kiwis (the bird and take the opportunity to watch a spine-tingling haka (war the fruit!), Sir Edmund Hillary, the All Blacks rugby team, dance) performance. Peter Jackson, Lorde, and Flight of the Conchords – to name a few. In New Zealand, our entrepreneurial spirit is hard to miss as we continually search for innovative solutions. Weta A study and travel experience in New Zealand is Workshop, pioneers in animation, and Medicine Mondiale, transformative. You’ll join a world-class education system, meet friendly locals, see amazing sights and creators of life-changing products such as the Mondiale enjoy a healthy work-life balance. Life Pod Incubator, are excellent examples of this. In our culture, we celebrate our indigenous people, At the University of Waikato, experience all of this and Māori, and their cultures and traditions are woven into more. We can’t wait to meet you. 2 The University of Waikato Why New Zealand? Innovation – thinking outside the square is the New Zealand way of life. Stunning landscapes – go from mountains to beaches to rainforests in one afternoon. Climate – our mild climate is perfect for getting out and exploring year-round. Indigenous culture – the culture and traditions of Maori, our indigenous people form a vital role in shaping our national identity. -

The University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand Hamilton, of University the Waikato, to Study in 2011 Choosing Students – for Prospectus International

THE UNIVERSITY OF WAIKATO, HAMILTON, NEW ZEALAND HAMILTON, WAIKATO, THE UNIVERSITY OF The University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand International Prospectus – For students choosing to study in 2011 INTERNATIONAL PROSPECTUS PROSPECTUS INTERNATIONAL THERE’S NO STOPPING YOU E KORE E TAEA TE AUKATI I A KOE For students choosing to study in 2011 students choosing For 2011 The University of Waikato Waikato International Private Bag 3105 Phone: +64 7 838 4439 Hamilton 3240 Fax: +64 7 838 4269 New Zealand Email: [email protected] Website: www.waikato.ac.nz Website: www.waikato.ac.nz/international ©The University of Waikato, June 2010. twitter.com/ StudyAbroad http:// _UOW Keep up-to-date up-to-date Keep latest news latest news and events with the with the Find us on uson Find facebook TTH FM Te Timatanga Hou Campus map College Hall TG TT TW TX TL TC TA Orchard Park 194H Te Kohanga Reo TSR Creche MS6 CRC Te Kura Kaupapa MS1 Maori o Toku ‘Station MS3 Mapihi Maurea Cafè’ MS5 B ELT MS4 Unisafe BX ‘Momento’ MS9 MSB UL3 MS8 Library Academy Bennetts Bookshop M 2 RB 1 NIWA Oranga Village Green LAW L TEAH A KP Landcare Student Research The Union SP Cowshed K Student SUB Village Rec S Centre FC1 SRC J Aquatic F G Research FC2 Centre I E CONF Chapel CHSS TRU Student LAIN R D Services Bryant EAS Hall LITB C ITS BL LSL GWSP Find us on iTunes U http://picasaweb. google.com/ Waikato. International 1 Contents 04 20 CHOOSE WAIKATO CHOOSE YOUR SUBJECT Welcome 4 Subjects 20 Why New Zealand? 6 Why Waikato? 8 Our beautiful campus – (65 hectares/160 acres) -

People Whose Writings Appear in This Issue and AEP Meeting Participants

People Whose Writings Appear in This Issue and AEP Meeting Participants Keio University, Tokyo, Japan, 22–23 March 2012 Department of Economics, Lund University, Sweden, 10–11 September 2012 Keio University, Tokyo, Japan, 5–6 October 2012 Shigeyuki Abe, Doshisha University, Japan Siow Yue Chia, Singapore Institute for Jiyoun An, Korea Institute for International International Studies, Singapore Economic Policy, South Korea Jonghwa Cho, Korea Institute for Anna Andersson, Lund University, Sweden International Economic Policy, South Magnus Andersson, Lund University, Korea Sweden Ji Chou, Shih Hsin University, Taiwan Bjorn Thor Arnarsson, Lund University, Peter C. Y. Chow, City College of New York, Sweden USA Prema-chandra Athukorala, Australian Chul Chung, Korea Institute for National University, Australia International Economic Policy, South Tobias Axelsson, Lund University, Sweden Korea Muhammad Chatib Basri, University of Iris Claus, Asian Development Bank, The Indonesia, Indonesia Philippines Carlos Bautista, University of the Stefan Collignon, Sant’Anna School of Philippines, the Philippines Advanced Studies, Italy Maria Socorro Gochoco-Bautista, Asian Nawalage S. Coolay, International Development Bank, The Philippines University of Japan, Japan Agnès Benassy, CEPII, France Georges de Menil, Paris School of Arne Bigsten, Gothenburg University, Economics, France Sweden Paul D. Deng, Copenhagen Business School, Anne Booth, School of Oriental and African Sweden Studies (SOAS), University of London, Barry Eichengreen, University of California, -

Issue Information

Negotiation and Conflict Management Research EDITOR Deborah A. Cai, Temple University EDITORIAL ASSISTANT Jennifer Midberry, Temple University ASSOCIATE EDITORS Tricia Jones, Temple University John Oetzel, University of Waikato Cheryl Rivers, Victoria University of Wellington EDITORIAL BOARD Noelle Aarts, Wageningen University, The Netherlands Michael Gross, Colorado State University Wendi Adair, Cornell University Fieke Harinck, Leiden University, The Netherlands Oluremi Ayoko, University of Queensland Jessica Jameson, North Carolina State University Linda Babcock, Carnegie Mellon University Sanda Kaufman, Levin College, Cleveland State University Bruce Barry, Vanderbilt University Deborah Kidder, University of Hartford Zoe Barsness, University of Washington, Tacoma Peter H. Kim, University of Southern California Max Bazerman, Harvard University Deborah Kolb, Simmons College School of Management Bianca Beersma, University of Amsterdam Roy J. Lewicki, The Ohio State University Bob Bies, Georgetown University Meina Liu, University of Maryland Lisa Blomgren Bingham, Indiana University Simone Moran, Ben Gurion University of the Negev Terry Boles, University of Iowa Kathleen O’Connor, Cornell University William Bottom, Washington University Jennifer Overbeck, University of Southern California Jeanne Brett, Northwestern University Robin Pinkley, Southern Methodist University Susan Brodt, Queen’s University Dean G. Pruitt, George Mason University Ronda Callister, Utah State University Jill M. Purdy, University of Washington Tacoma Peter Carnevale, -

Asia Canada Europe Multiple Countries Oceania

INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY FAIR & CONFERENCE SAIGON SEPTEMBER 28, 2019 @ SAIGON SOUTH INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL ASIA Sustainability Management School of Switzerland Emory University The Catholic University of the West Endicott College Chulabhorn International College of Medicine Trinity College Dublin Florida International University Duke Kunshan University University College London Fordham University Ecole Hoteliere de Lausanne University of Birmingham Georgia State University Education University of Hong Kong University of Dundee Gettysburg College Hong Kong Baptist University University of Edinburgh Illinois Wesleyan University Hong Kong Polytechnic University University of Essex Ithaca College Mahidol University International College University of Glasgow Lewis & Clark College Nagoya University University of Gloucestershire Loyola Marymount University Nagoya University of Commerce & Business University of Huddersfield Marist College National Taiwan University University of Leeds Maryland Institute College of Art New York University Shanghai University of Manchester Massachusetts College of Art & Design Rangsit University University of Nottingham Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences University Ritsumeikan University University of Reading Missouri Western State University Singapore Institute of Management University of Southampton Muhlenberg College Temple University, Japan Campus University of Sussex Northeastern University Thammasat Business School University of Veterinary Medicine Budapest Ohio University University of -

Pathways to the University of Waikato

Pathways to the University of Waikato 2018/19 Foundation Studies and English Language Programmes pathways.waikato.ac.nz Welcome to Waikato ACADEMIC PATHWAYS Key facts Welcome to the University of Waikato, located in Hamilton, ο Student population comprised of more HIGH SCHOOL IN YOUR COUNTRY New Zealand. The University is truly world-class, ranked in than 80 different nationalities the top 1.1% of universities worldwide.* Experience smaller ο Study, live, socialise at our all-in-one class sizes, accessible staff, and a welcoming and diverse campus student community. ο Accessible academic staff WAIKATO PATHWAYS ACADEMIC ENGLISH ο More than 90% of surveyed students COLLEGE FOUNDATION PROGRAMME would recommend the University to others PROGRAMME Students first Pathway Student Visa (International Student Barometer 2017) Students’ interests are at the heart of the University A Pathway Student Visa may be granted for up to a ο Ranked in the top 1.1% of universities motto of ‘Ko Te Tangata’, meaning ‘For the People’. maximum of five years and allows a student to undertake Flexible degree structures allow students to follow their up to three consecutive programmes of study on a single in the world (QS World University Rankings 2019) interests and career plans. The University’s emphasis student visa. For more information visit immigration.govt.nz ο 13 subjects ranked in the top 300 on practical experiences means students are ready POSTGRADUATE (QS World University Rankings 2018) BACHELORS DEGREE to go from the classroom into a successful career. Quality assurance DEGREE The University of Waikato took part in the Cycle 5 ο Triple Crown accredited business school Bridging the gap to university Academic Audit in association with the Academic Quality Waikato Pathways College offers a variety of courses Agency for New Zealand Universities (AQA) and received which will help you progress to the University. -

Waikato Journal of Education Education of Journal Waikato Waikato Journal of Education Te Hautaka Matauranga¯ O Waikato Waikato Journal of Education

School of Education Te Kura Toi Tangata Waikato Journal of Education Waikato Journal of Education Te Hautaka Matauranga¯ o Waikato Waikato Journal of Education ISSN 2382-0373 Website: http://wje.org.nz Title of Issue/section: Volume 22, Issue 4, 2017 Editor/s: Noeline Wright To cite this article: Amundsen, D., Msoroka, M., & Findsen, B. (2017). “It’s a case of access.” The problematics of accessing research participants. Waikato Journal of Education, 22(4), 5–17. doi:10.15663/wje.v22i4.425 To link to this article: doi:10.15663/wje.v22i4.425 To link to this volume doi:10.15663/wje.v22i4 Copyright of articles Creative commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ Authors retain copyright of their publications. Author and users are free to: • Share—copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format • Adapt—remix, transform, and build upon the material The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms. • Attribution—You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use • NonCommercial—You may not use the material for commercial purposes. • ShareAlike—If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. Terms and conditions of use For full terms and conditions of use: http://wje.org.nz/index.php/WJE/about/editorialPolicies#openAccessPolicy and users are free to • Share—copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format • Adapt—remix, transform, and build upon the material The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms.