CRM Success Through Enhancing the Project Management Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dynamics 365 Business Central On-Premises Licensing Guide

Dynamics 365 Business Central on-premises Licensing Guide October 2018 Microsoft Dynamics 365 Business Central on-premises Licensing Guide | October 2018 Contents How to buy Dynamics 365 Business Central on-premises ................................................................................... 1 Perpetual Licensing ................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Deploying Your Self-Managed Solution in an IaaS Environment ........................................................................................................... 2 Subscription Licensing ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Choosing the Appropriate SAL Type .................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Subscription Licensing Term .................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 How to use Dynamics 365 Business Central on-premises ................................................................................... 4 Licensing Requirement for Internal Users........................................................................................................................................................ -

Planung & Konsolidierung

Online und Guides Online und Guides www.isreport.de 22. Jahrgang 5/2018 10 EUR Planung & Konsolidierung Weitere Themen: • Self-Service BI – Mobile Anwendungen für Planung & Konsolidierung • ERP für Fertigungsunternehmen • Erfolgreiche Software-Implementierung Zertifi katskurs Chief ERP Projekt Manager Kurs Q1/2019: 16. – 18.01.2019 (Modul 1) und 20. – 22.02.2019 (Modul 2) Kurs Q2/2019: 10. – 12.04.2019 (Modul 1) und 08. – 10.05.2019 (Modul 2) Veranstaltungsort: Cluster Smart Logistik auf dem RWTH Aachen Campus ww.cerp.rwth-campus.com Anzeige EDITORIAL Anregungen DeltaApp Das Daumen-Dashboard von Bissantz STEFAN RAUPACH Mitinhaber des is report O´zapft is... Mit zwei Schlägen hat der Münchner erfahren, wieviel diese EU-Verord- OB das diesjährige Oktoberfest eröff- nung die deutschen Unternehmen net. Da der Wettergott wie fast immer gekostet hat. Der Zeitaufwand, die den Wirten und Schaustellern gnädig Implementierungskosten, dadurch gestimmt ist, strömen auch dieses bedingte Produktivitätsausfälle, ggf. Jahr wieder Millionen von Besuchern zusätzliche Personalkosten, einmal Was nicht auf den Bildschirm eines auf die Münchner Theresienwiese. monetär zu erfassen, ist nahezu ein Smartphones passt, geht im hek- Ein Zustand, von dem die meisten Ding der Unmöglichkeit. Welcher tischen Management-Alltag kaum Messeveranstalter nur träumen kön- Nutzen steht dem gegenüber? noch durch das Nadelöhr der nen. Allen voran die CEBIT. Während Damit sind wir auch schon wieder knappen Aufmerksamkeit. klar fokussierte Messen bzw. Kon- am Ende unseres kurzen Jahresrück- Die DeltaApp komprimiert Daten- gresse wie z.B. das ControllerForum blicks 2018. Auch wenn es die letzte navigation, Abweichungsanalyse des ICV, die BI Conference von TDWI/ Ausgabe des is report in 2018 ist, wer- SigsDataCom oder die Personalmes- de ich mich beherrschen und keine und Performance Management – sen sehr gut besucht bzw. -

Data Quadrant Report

April 2020 DATA QUADRANT REPORT Enterprise Resource Planning 1107 22 Reviews Vendors Evaluated Enterprise Resource Planning Data Quadrant Report Table of How to Use the Report Info-Tech’s Data Quadrant Reports provide a comprehensive evaluation of popular products in the Enterprise Resource Planning market. This buyer’s guide is designed to help prospective Contents purchasers make better decisions by leveraging the experiences of real users. The data in this report is collected from real end users, meticulously verified for veracity, Data Quadrant.................................................................................................................. 6 exhaustively analyzed, and visualized in easy to understand charts and graphs. Each product is compared and contrasted with all other vendors in their category to create a holistic, unbiased view Category Overview .......................................................................................................7 of the product landscape. Use this report to determine which product is right for your organization. For highly detailed reports Vendor Capability Summary ................................................................................ 9 on individual products, see Info-Tech’s Product Scorecard. Vendor Capabilities .....................................................................................................13 Product Feature Summary .................................................................................25 Product Features ..........................................................................................................31 -

Top 20 Enterprise Resource Planning Software Report

2017 EDITION TOP 20 ENTERPRISE RESOURCE PLANNING SOFTWARE REPORT Comparison of the Leading ERP Software Vendors Overview of ERP Software Solutions In today’s highly competitive marketplace, implementing software to streamline operational processes can mark the difference between a business struggling to stay afloat and one that’s flourishing. Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) software exists as one of the most comprehensive solutions for companies in need of back-end organization, with features tailored to businesses of all sizes and industries. An ERP system allows companies to centralize many key elements of their production line, building a more productive and cost-effective business model. Originally designed for enterprise-level businesses, ERP solutions today will add value to companies of varying sizes by more efficiently monitoring and operating daily tasks. Enterprise planning software also reduces time spent on repetitive or overlapping activities by establishing a centralized database that coordinates interdepartmental data assignments and more effectively allocates resources. Even if your existing business processes operate smoothly, your company can still find value in the increased productivity and tighter budget control that an ERP system offers. Understanding the Different ERP Modules Today’s ERP solutions offer a variety of modules to better serve the unique needs of companies in diverse industries. Some of the most common ERP modules are listed below. Manufacturing Ideal for businesses in the manufacturing industry, this ERP module offers enhanced product assembly tools to streamline product design and creation, optimize production processes and automate materials management. Manufacturing ERP software will also better manage day-to-day procedures, reducing operating costs and increasing the productivity of your manufacturing cycle. -

Microsoft Dynamics 365 Is?

Wondering what Microsoft Dynamics 365 is? Read our quick overview. High-level… what is Dynamics 365? • Dynamics 365 is a cloud-based combination of ERP and CRM • It was built by Microsoft for maximum flexibility and extensibility • It is unlikely that Dynamics 365 will fit an organizations’ needs perfectly, but Microsoft’s vision is that businesses will find the customizations they need on Microsoft AppSource • It is built on a common data model which allows for tighter integrations with other apps that have a standardized API • There are 2 Editions of Dynamics 365: 1. Enterprise Edition and 2. Business Edition 1. Dynamics 365, Enterprise Edition • The “Enterprise” version is a newly developed combination of Microsoft Dynamics AX and Microsoft Dynamics CRM • Microsoft recommends Dynamics 365, Enterprise Edition for companies with more than 250 employees • It is the higher-powered of the two offerings Dynamics 365, Enterprise Edition, Comes with 6 Modules 1. Finance & Operations (Previous core functionality of MS Dynamics AX) 2. Sales (Previous core functionality of MS Dynamics CRM) 3. Marketing (Through partnership with Adobe) 4. Customer Service (A combination of functionality from MS Dynamics CRM, functionality from Parature, and new functionality) 5. Project Service (Previously available as an ext for MS Dynamics CRM) 6. Field Service (Also previously available as an extension for MS Dynamics CRM). Dynamics 365, Enterprise Edition, Additional Modules (you can add them) • Dynamics 365, Enterprise Edition, has 2 additional modules that can be purchases separately. They are: 1. Talent (This is the HCM module of Dynamics AX) 2. Retail (This is the retail module of Dynamics AX) 2. -

TFG ERP PAC4 Sergi Muñoz Garcia

Implantació d’ERP en una distribuïdora de begudes Sergi Muñoz Garcia Grau d’Enginyeria Informàtica Sistemes d’Informació Integrats (ERP) Xavier Gonzalez Farran María Isabel Guitart Hormigo 8 de juny de 2021 Aquesta obra està subjecta a una llicència de Reconeixement-NoComercial- SenseObraDerivada 3.0 Espanya de Creative Commons i FITXA DEL TREBALL FINAL Implantació d’un ERP en una distribuïdora Títol del treball: de begudes Nom de l’autor: Sergi Muñoz Garcia Nom del consultor/a: Xavier Gonzalez Farran Nom del PRA: María Isabel Guitart Hormigo Data de lliurament (mm/aaaa): 06/2021 Titulació o programa: Grau d’Enginyeria Informàtica Àrea del Treball Final: Sistemes d’Informació Integrats (ERP) Idioma del treball: Català Paraules clau ERP, distribuïdora, begudes Resum del Treball (màxim 250 paraules): Amb la finalitat, context d’aplicació, metodologia, resultats i conclusions del treball Aquest treball té com a objectiu identificar els requeriments funcionals i no funcionals que requereix Àmfora de Baco, petita companyia distribuïdora de begudes alcohòliques, per a determinar quin ERP s’adapta millor a les seves necessitats. El treball segueix una estructura temporal lògica d’identificació del sector en el que opera la companyia i de la pròpia companyia, seguit de la identificació de la tecnologia actual i dels requisits necessaris. Posteriorment, s’han identificat els diferents ERP que hi ha al mercat en codi obert, ja que s’ha estimat que era l’opció més econòmica donades les característiques d’Àmfora de Baco. D’entre els ERP identificats s’ha seleccionat l’opció més adient mitjançant un scoring funcional. A continuació s’ha identificat quins mòduls caldria implementar per poder donar resposta als requisits funcionals identificats, de forma que la solució s’adapti a les necessitats de la Companyia. -

The Forrester Wave™: Microsoft Dynamics 365 Services, Q4 2017

FOR APPLICATION DEVELOPMENT & DELIVERY PROFESSIONALS The Forrester Wave™: Microsoft Dynamics 365 Services, Q4 2017 The 13 Providers That Matter Most And How They Stack Up by Ashutosh Sharma and Somak Roy December 20, 2017 Why Read This Report Key Takeaways Buyers of Microsoft Dynamics 365 are increasingly Avanade, KPMG, Hitachi Solutions, Wipro, And enterprises. Our 30-criteria evaluation of Microsoft DXC Technology Lead The Pack Dynamics 365 service providers identified the Forrester’s research into the Microsoft Dynamics 13 most significant ones — Avanade, DXC 365 services landscape reveals a market where Technology, HCL Technologies, Hitachi Solutions, Avanade, KPMG, Hitachi Solutions, Wipro, and IBM, Infosys, KPMG, Larsen & Toubro Infotech DXC lead the pack. HCL, PwC, Infosys, TCS, (LTI), PwC, Sonata Software, Tata Consultancy IBM, and Sonata Software offer competitive Services (TCS), Tech Mahindra, and Wipro — and options. LTI and Tech Mahindra have some researched, analyzed, and scored them. This catching up to do. report shows how each provider measures up The Dynamics Platform Becomes A Lever For and helps application development and delivery Better CX, Not Just A System Of Record (AD&D) professionals make the right choice. The goal of CRM design is now more often about empowering front-end personnel with the data they need to serve customers better and improve the customer experience (CX). To a lesser extent, the Microsoft Dynamics enterprise resource planning (ERP) portfolio is following suit. Consulting Capabilities And Scale Are Key Differentiators Successful vendors are differentiating via their consulting capabilities, scale, and industry-specific capabilities. Consulting is becoming key as more enterprises make Dynamics 365 a central part of their digital transformation and it remains difficult to find skilled Dynamics resources. -

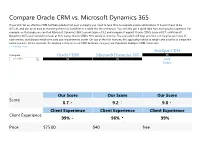

Compare Oracle CRM Vs. Microsoft Dynamics 365

Compare Oracle CRM vs. Microsoft Dynamics 365 If you wish for an effective CRM Software product for your company you need to take time to evaluate several alternatives. It doesn’t have to be difficult, and can be as easy as matching their functionalities in a table like the one below. You will also get a quick idea how each product operates. For example, on this page you can find Microsoft Dynamics 365’s overall score of 9.2 and compare it against Oracle CRM’s score of 8.7; or Microsoft Dynamics 365’s user satisfaction level at 96% versus Oracle CRM’s 99% satisfaction score. The evaluation will help you find out the pros and cons of each service, and choose which one suits you requirements better. On top of the rich features, the application which is simple and intuitive is always the better product. At the moment, the leading solutions in our CRM Software category are: Pipedrive, HubSpot CRM, Freshdesk. < Previous Next > HubSpot CRM Compare Oracle CRM Microsoft Dynamics 365 VS ---select option--- VS VS FREE Partner Our Score Our Score Our Score Score 8.7 9.2 9.8 Client Experience Client Experience Client Experience Client Experience 99% 96% 99% Price $75.00 $40 free Price Scheme Monthly payment | Annual Subscription Monthly payment | Quote-based Free Full Review Review of Oracle CRM Review of Microsoft Dynamics 365 Review of HubSpot CRM General Info Oracle CRM handles all customer HubSpot CRM is the winner of our 2018 relationship management issues and Cloud-based CRM solution Microsoft Best CRM Award. -

CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIP MANAGEMENT SOFTWARE February 2018

CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIP MANAGEMENT SOFTWARE February 2018 Powered by Methodology CONTENTS 4 Introduction 6 Defining CRM Systems 7 The Quadrant 8 CRM FrontRunners Index 33 Runners Up 53 Methodology Basics FRONTRUNNERS 9 Pipedrive 10 HubSpot CRM 11 Close.io 12 amoCRM 13 Salesforce 14 Nimble 15 ProsperWorks CRM 16 Agile CRM 17 Microsoft Dynamics 365 18 PipelineDeals 19 Base 20 Velocify 21 iContact 22 Highrise 23 Vtiger CRM On Demand 24 Hatchbuck 25 Daylite for Mac 26 Teamgate 27 Gold-Vision CRM 28 bpm’online 29 Less Annoying CRM 30 ONTRAPORT 31 Commence CRM 32 SalesNOW INTRODUCTION his FrontRunners analysis is a data-driven Tassessment identifying products in the Customer Relationship Management software market that offer the best capability and value for small businesses. For a given market, products are evaluated and given a score for the capability (x-axis) and value (y-axis) they bring to users. FrontRunners then plots the top 25-30 products in a quadrant format. In the Customer Relationship Management FrontRunners graphic, the Capability axis starts at 3.20 and ends at 4.60, while the Value axis starts at 3.80 and ends at 4.70. To be considered for the Customer Relationship Management FrontRunners, a product needed a minimum of 20 user reviews, a minimum capability user rating score of 4.1 and a minimum value user rating score of 4.1. In most cases, we evaluate hundreds of products and feature 20- 25 as FrontRunners; all products that qualify as FrontRunners are top performing products in their market. FEBRUARY 2018 4 Introduction Each product falls within a designated quadrant based on their axis scores. -

Momentum Grid® Report for ERP Systems Winter 2021

Momentum Grid® Report for ERP Systems Winter 2021 Trending ERP Systems Momentum scores for ERP Systems are shown below. The Momentum Grid® highlights each product’s Momentum score on the vertical axis and the product’s Satisfaction score on the horizontal axis. These scores are based on G2’s Satisfaction and Momentum algorithms. Products with a top 25% Momentum Grid® score are shown within the shaded area below. Momentum Leaders Momentum Score Satisfaction G2 Momentum Grid® Scoring (Trending ERP Systems continues on next page) © 2021 G2, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form without G2’s prior written permission. While the information in this report has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, G2 disclaims all warranties as to the accuracy, completeness, or adequacy of such information and shall have no liability for errors, omissions, or inadequacies in such information. 1 Momentum Grid® Report for ERP Systems | Winter 2021 Trending ERP Systems (continued) ERP Systems Momentum Grid® Description A product’s Momentum score is calculated by a proprietary algorithm that factors in social, web, employee, and review data that G2 has deemed influential in a company’s momentum. Software buyers can compare products in the ERP Systems category according to their Momentum and Satisfaction scores to streamline the buying process and quickly identify trending products. For sellers, media, investors, and analysts, the Momentum Grid® provides benchmarks for product comparison and market trend analysis. Badges are awarded to products with the top Momentum Grid® scores. Products included in the Momentum Grid® for ERP Systems have received a minimum of 10 reviews. -

How Much Does an ERP System Cost? 2021 PRICING GUIDE How Much Does an ERP System Cost? 2021 PRICING GUIDE

How Much Does an ERP System Cost? 2021 PRICING GUIDE How Much Does an ERP System Cost? 2021 PRICING GUIDE For any business investing in an enterprise resource planning (ERP) system, pricing is an important factor. ERP software isn’t cheap, and prices vary depending prospects and customer pipelines. Users can also on the type of deployment, number of users and level manage marketing tasks, including advertising and of customizations. lead generation campaigns. Some vendors publicly display pricing on their Supply Chain – The supply chain module tracks website, especially for cloud ERP solutions, while products from manufacturing to warehouse to others only provide a quote after finding out a distributors to customers. Features include supplier company’s business requirements. scheduling, purchasing, inventory, claim processing, shipping, tracking and product returns. We’ve put together this detailed guide on the various ERP pricing models, implementation costs and Inventory Management – Using the inventory examples of popular ERP vendor pricing. management module, businesses can monitor What Is an ERP? materials and supplies through inventory control, purchase orders, automatic ordering and inventory scanning. An enterprise resource planning system helps organizations manage business functions and Manufacturing – Manufacturers and other production- streamline operations with a centralized database and oriented facilities can use the manufacturing module a user-friendly interface. Companies use ERP software to manage their shop floors, looking at elements to standardize business processes, collect operational such as work orders, bill of materials, quality control, data, improve supply-chain efficiency, promote engineering, manufacturing process and planning, data-driven strategies and increase collaboration and product lifecycle management. -

SYNC for Microsoft Dynamics NAV and Microsoft Dynamics 365

SYNC for Microsoft Dynamics NAV and Microsoft Dynamics 365 Commercient SYNC for Microsoft Dynamics NAV and Microsoft Dynamics 365 Commercient SYNC, the #1 data integration platform that integrates your Microsoft Dynamics NAV (Navision), otherwise known as Microsoft Dynamics Business Central with Microsoft Dynamics 365. The Commercient SYNC Agent is rapidly deployable and gives you access to your Microsoft Dynamics NAV customer and order information in Microsoft Dynamics 365. We work with the following: Microsoft Dynamics GP (Great Plains), Microsoft Dynamics AX (Axapta), and Microsoft Dynamics SL (Solomon). About SYNC: Commercient SYNC is created by ERP and CRM data integration experts. By having that, SYNC creates a simple data integration pathway between your Microsoft Dynamics NAV and Microsoft Dynamics 365. Once the data integration takes place, your Microsoft Dynamics NAV data is automatically loaded into your Microsoft Dynamics 365 without programming, coding, mapping or servers required. SYNCing data is a cloud-based experience that ensures your data is protected. SYNC has the following benefits: ● Data integrated from Microsoft Dynamics NAV to Microsoft Dynamics 365 becomes native data inside Microsoft Dynamics 365 CRM. Being native data inside the CRM means bringing data from your Microsoft Dynamics NAV over to Microsoft Dynamics 365 in which you can perform any function from that data and manipulate it to the way you need it, for example, connecting to third-party apps and creating dashboards ● Inside Microsoft Dynamics 365, the system provides the function of a user-friendly search engine to look up data that is SYNCed from Microsoft Dynamics NAV because the data is native, it is searchable.