Budgeting in an Era of Austerity and State Capture: a Five-Year Review of Budget Policies and Outcomes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three Priests Ordained for the Diocese of Oakland

The Catholic Voice is on Facebook VOL. 57, NO. 11 DIOCESE OF OAKLAND JUNE 10, 2019 www.catholicvoiceoakland.org Serving the East Bay Catholic Community since 1963 Copyright 2019 Three priests ordained for the Diocese of Oakland By Michele Jurich Staff writer Addressing the three men before him, “Soon-to-be Father Mark, Father John and Father Javier,” Bishop Michael C. Barber, SJ, told them, “you are called and chosen” and told them what serving means today. In front of a crowded Cathedral of Christ the Light Bishop Barber told them he was zeroing in on the third vow they would take shortly, to celebrate the Mass and administer the Sacrament of Confession worthily. “You will never violate the Seal of Confession,” Bishop Barber told the three new priests. “No state or government can oblige you to betray your penitents.” Legislation — SB 360 — has passed the state Senate and is moving to the Assembly. It will compel a priest to reveal to police some sins he hears in confession. The new priests, John Anthony Pietruszka, 32, Javier Ramirez, 43, and Mark Ruiz, 56, listened attentively. Father Pietruszka is from Fall River Massachusetts; Father Ramirez from Culiacán, Sinaloa, Mexico; and Mark Father Ruiz was born and raised in Oakland. They would not be alone, the bishop assured them. To show that support, more than 70 VOICE CATHOLIC PACCIORINI/THE C. ALBERT priests, mostly diocesan, were present to With Bishop Michael C. Barber, SJ, at left, the trio of men prostrate themselves at the altar. This symbolizes each man’s offer blessings and the sign of peace to unworthiness for the office to be assumed and his dependence upon God and the prayers of the Christian community. -

Isabella Mils M

mulit bur btonittr, ^ C. _id. ..i1OTTE(R, Editor cS- Publisher. Established by SAMUEL MOTTER in 1879. TEP.,115.4.z.c o a Year in Advance. VOL. XIII. EMMITSBURG-, MARYLAND, FRIDAY, APRIL, 22, 1892. SONG. DIRECTORY A SPRING l and dry the hides, and "keep speeches, and last, though not least, A LEGAL vtEw. FOR FREDERICK COUNTY Old Mother Earth woke up from sleep, house" generally. Three, including divine service was held with a hymn Qtlad'w Little ea ery ef it Lawyer and a Railroad Aceidi nt. And found she was cold and bare; myself and Vandewater, were by and prayer, led by a devout man Circuit Com t. The Winter was o'er, the Spring was lie sat just opposite to me in the "drawing straws" detailed to follow Chief Judge--Hon. James atesheery. by the name of Captain Burehard, Amioclate Judges-Hon. John T. Vinson and near, train, and from the legal documents the hunters with the wagon. The and we closed the night's festivi- Bon. John A. Lynch. And she had not a dress to wear. Attorney-Edw. S. Eicheitiorger. he was perusing .had lit doubt State's hunters were paired off in couples Clerk of the Court-John L. Jordan. "Alas l" she sighed, with great dismay, ties by voting Roland Simmons the Court. that he was a lawyer. I looked tint Orphan's "Oh, where shall I get my clothes? to describe a circle of five or six hero of the day. elteleee-Betiard Collitiower, John R. Mille. of the window as the blew There's whistle Harriman not a place to buy a suit, miles, each couple having a horn, Our sport was kept up for six Register of Wills-James K. -

DEPUTY VICE-CHANCELLOR: ACADEMIC Reflective Report 2020

DEPUTY VICE-CHANCELLOR: ACADEMIC Reflective Report 2020 Contents DEPUTY VICE-CHANCELLOR (ACADEMIC) Reflective Report 2020 2 FACULTY OF ARTS AND HUMANITIES 26 FACULTY OF COMMUNITY AND HEALTH SCIENCES 46 FACULTY OF DENTISTRY 62 FACULTY OF EDUCATION 80 FACULTY OF ECONOMIC AND MANAGEMENT SCIENCES 108 FACULTY OF LAW 130 FACULTY OF NATURAL SCIENCES 140 ACADEMIC PLANNING UNIT 156 COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT UNIT 160 CENTRE FOR INNOVATIVE EDUCATION & COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGIES (CIECT) 168 CENTRE FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS 186 DIRECTORATE OF LEARNING, TEACHING AND STUDENT SUCCESS (DLTSS) 192 page Deputy Vice-Chancellor: Academic | Reflective Report 2020 1 DEPUTY VICE-CHANCELLOR: ACADEMIC PROF VIVIENNE LAWACK Reflective Report 2020 Since 2017, every Dean and Director within my line has compiled a Reflective Report, which I consolidate, adding my own reflections. The consolidated DVC (Academic) Reflective Report is intended to reflect on the state of the academic project, through the lenses of the seven faculties at the University of the Western Cape (UWC), together with the academic professional support directorates within this portfolio. Given the cataclysmic effects of the ongoing pandemic, it would be remiss not to reflect fully on the impact of the pandemic on the academic project and how we managed to complete the 2020 academic year and start the 2021 academic year timeously. This Reflective Report contains an overview of our academic approach and decision-making during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, as well as a self-evaluation of the most pertinent work done during the course of the current Institutional Operation Plan (IOP 2016—2020), including the successes and work that need to be consolidated or accelerated, and opportunities for innovation in the next IOP. -

Narratives of Perceived Social Support As a Mediator for Increased Coping Resources and Optimism Among Cancer Patients and Survi

NARRATIVES OF PERCEIVED SOCIAL SUPPORT AS A MEDIATOR FOR INCREASED COPING RESOURCES AND OPTIMISM AMONG CANCER PATIENTS AND SURVIVORS by TAVARI TAYLOR BROWN A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty in the Counselor duration and Supervision Program of Penfield College at Mercer University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Atlanta, GA 2014 COPYRIGHT 2015 UMI Number: 3662748 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Di!ss0?t&Ciori Publishing UMI 3662748 Published by ProQuest LLC 2015. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 COPYRIGHT 2015 TAVARI TAYLOR BROWN ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you, Terrence Dominic Brown for nearly five years of evenings alone, waking up at 2:00 a.m. wondering why your wife is in another room reading or typing under dim light, and for a commitment to our marriage. Thank you, Talia G. Brown for being the best fetus, neonate, and daughter in the history of the world ever known to mankind! To “Dee,” the pink-ribbon binding four out of five narratives. We miss you so! Thank you for sharing your wonderful light, life, and “effervescence” as one interview participant stated. -

A Framework for Progressively Improving Small Area Population Estimates

J. R. Statist. Soc. A (2004) 167, Part 1, pp. 5–36 A framework for progressively improving small area population estimates Philip Rees, University of Leeds, UK Paul Norman University of Manchester, UK and Dominic Brown University of Queensland, Australia [Received April 2002. Final revision May 2003] Summary. The paper presents a framework for small area population estimation that enables users to select a method that is fit for the purpose.The adjustments to input data that are needed before use are outlined, with emphasis on developing consistent time series of inputs. We show how geographical harmonization of small areas, which is crucial to comparisons over time, can be achieved. For two study regions, the East of England and Yorkshire and the Humber, the dif- ferences in output and consequences of adopting different methods are illustrated. The paper concludes with a discussion of how data, on stream since 1998, might be included in future small area estimates. Keywords: Estimation methods; Geographical harmonization; Population estimates; Small area populations 1. Introduction Changes in small area populations occur through aging and the processes of natural change, births and deaths. Population change also occurs through migration within and between small areas, whether urban, suburban or rural, with different migration patterns for people of differ- ent age groups. In some locations the tendency is for people to age in situ; other areas have more transient populations. In the UK, since information from the decennial census, the principal source of sociodemographic data, is only available for one date per decade, there is a need to esti- mate small area populations from the latest census forwards and then to revise these estimates when the next census is published. -

Curtiss Wins $10,000 Prize Thirteenth Annual High

The bronidr. CENTURY TERMS—$1.00 A YEAR IN ADVANCE STERLING GALT.EDITOR AND PROPRIETOR ESTABLISHED OVER A QUARTER OF A FRIDAY-, JITINE 3, 1910 NO. 3 VOL. XXXII El\INITTSBUTIG, MARYLAN D. CURTISS WINS THIRTEENTH ANNUAL HIGH SCHOOL COMMENCEMENT EXERCISES HOW TO RULE ; the Graduates by BY THEODORE $10,000 PRIZE The thirteenth annual commencement Music Address to John T. Superintendent of of the Emmitsburg High School has oc- Prof. White, Frederick county; "BIG STICK" AT WORK ALBANY TO NEW YORK cupied the attention of the people for the Public Schools of "What the Tramp Said," the past week. This, in the words of Recitation, I I Harbaugh ; Presentation of Di- Colonel Roosevelt Dazes En- Remarkable Trip of Amer- the handsome souvenir programme is- Naomi first annual plomas and Farewell Speech to Class glish Audience ican Aeronaut sued by the class, was "the commencement week." The exercises + by Prof. P. F. Strauss; Class Ode ; Sunday when Rev. Charles Benediction by Rev. Charles Reinewald, ON BRITISH EGYPTIAN POLICY RECORD FOR SPEED AND DANGER began on Reinewald, D.D., delivered the bacca- D. D. During the principalship of Prof. Gives Advice to British Empire, Twists Outstrips Special Train at laureate sermon to the graduates. A Aviator Strauss the school has maintained a de- the Lion's Tail, Pounds Home His in Covering 137 Miles in very large audience attended this ser- Points bating team which met and defeated a Advice and Sits Down to Two Hours and 32 Minutes.— vice and special music by the choir similar team from the Brunswick High Admire Gift. -

All Saints' College 30Th Edition

Columba 2010 – Columba 2010 Celebrating 30 years Celebrating 30 years ALL SAINTS’ COLLEGE Ewing Avenue Bull Creek Western Australia 6149 PO Box 165 Willetton Western Australia 6955 Junior School: Telephone 08 9313 9334 Facsimile 08 9313 5917 Senior School: Telephone 08 9313 9333 Facsimile 08 9310 4726 www.allsaints.wa.edu.au Contents Autographs From the Publications Captain 2 SENIOR SCHOOL From the Principal 3 HOUSES From the Chair of the Board 4 Cowan 70 Chaplain Chatter 5 Cowan House Captains’ Report 72 From the Parents and Friends’ Society 6 Durack 74 Durack House Captains’ Report 76 CAPTAINS Forrest 78 Forrest House Captains’ Report 80 2010 Student Council 7 Murdoch 82 From the College Captains 8 Murdock House Captains’ Report 84 From the Academic & Performing Arts Captains 9 O’Connor 86 From the Functions & Sports Captains 10 O’Connor House Captains’ Report 88 From the Community Service & Stirling 90 Environment Captains 11 Stirling House Captains’ Report 92 JUNIOR SCHOOL YEAR PAGES From the Head of Junior School 14 Year 11 95 2010 Junior School Student Leaders 15 Year 10 96 From the Junior School Councillors 16 Year 9 97 From the Community Service & Year 8 98 Environment Captains 17 Year 7 99 Transition Program 100 HOUSES Peer Support Program 101 Bussell 18 Bussell House Captains’ Report 19 CAMPS & TRIPS Drummond 20 French Trip & Italian Trip 103 Drummond House Captains’ Report 21 Mt Hotham Ski Trip & P&L Canberra Trip 104 Molloy 22 Choral Camp & Instrumental Camp 105 Molloy House Captains’ Report 23 Rottnest Art Camp & Busselton -

Firefighter Accused of Assaulting Dispatcher

www.StonebridgePress.com Friday, May 10, 2019 Newsstand: 75 cents Firefighter accused of assaulting dispatcher BY ANNIE SANDOLI Sunday, April 28 at the judge ordered that he be outcome of his next court of court proceedings as of grabbing, kissing, and CORRESPONDENT Sturbridge Public Safety released on a $200 bail date. Auburn Fire Chief well as our own internal groping her without her Complex. with the condition of his Stephen M. Coleman, Jr. investigation on the mat- consent multiple times STURBRIDGE— According to Timothy release being that that released a statement on ter. As this is a person- after he returned from Auburn firefighter Adam J. Connolly, Director of he stay away from and social media recognizing nel matter, we will not responding to an ambu- P. LaFlash of Sturbridge, Communications for have no contact with the the incident. comment further until lance dispatch for a car who is a full-time fire the office of Worcester victim. He is due back in “We are aware of the this case makes its way accident. She also said lieutenant for the County District Attorney court on Monday, June allegations against one through the court system he had been sending her Auburn Fire Department Joseph D. Early, Jr., 10. of our members that and all investigations are inappropriate messages and has been working LaFlash, 36, was charged The Town of Sturbridge occurred in the Town of complete.” over text and through as a part-time call fire- with and pleaded not has suspended LaFlash’s Sturbridge while work- According to a police Facebook. -

Minutes of the May 9, 2018 Legislature Meeting Were Approved Upon Motion of Legislator Maha Seconded by Legislator Dibble, Carried Unanimously

TENTH DAY GENESEE COUNTY LEGISLATURE Batavia, New York Wednesday, May 23, 2018 The Genesee County Legislature met in Regular Session on Wednesday, May 23, 2018 at 5:30PM at the Old Courthouse 7 Main Street, Batavia, New York. Legislator Maha assisted with the audit. Prayer was offered by Legislator Torrey followed by the Pledge to the Flag. In addition to our regular meeting Chairman Bausch opened a Public Hearing on Local Law Introductory No. 3, Year 2018 A Local Law Pursuant To Section 487(8)(A) Of The Real Property Tax Law To Eliminate A Tax Exemption For Certain Enumerated Energy Systems. The following signed in to speak at the Public Hearing; Padma Kacthuri-rangan, Brant Penman, Tim Grooms, Leo Lynn and Chris Deleo. Speakers comments included concern that businesses would look to locate in adjacent counties that offer the exemption, concern with how systems will be assessed, clarification that existing systems will be grand-fathered in, why the State offered the 15-year exemption, what taxing jurisdictions have the authority to opt-out, and that the point of the exemption is to encourage green energy systems and reduce the carbon foot- print, and a wind & solar company employee who has clients in the county commented that IDA’s enter into PILOTS. Legislator Clattenburg provided comments since the matter went through the Ways & Means Committee. The law does not allow taxing jurisdictions to distinguish between residential or commercial projects therefore if the County passed a local law to opt-out of the 15-year exemption on the assessed value of the solar or wind system it has to be for both home-owners and businesses. -

March 11 – 17, 2021

BEECH GROVE • CENTER GROVE • GARFIELD PARK & FOUNTAIN SQUARE • GREENWOOD • SOUTHPORT • FRANKLIN & PERRY TOWNSHIPS FREE • Week of March 11-17, 2021 Serving the Southside Since 1928 ss-times.com FREE COOKIE DOUGH WITH PURCHASE OF A LARGE OR FAMILY SIZE PIZZA (excludes XLNY and LTOs) Enter Code INDYCD Why not at checkout at papamurphys.com EXPIRES 05/15/2021 Special offer for The Southside Times Readers! now? ORDER IN-STORE OR ONLINE TODAY! Three Southside graduates ‘go all out’ in starting their production Available at these 2 Locations ONLY company, 2W Productions PAGE 4 plus Online: Beech Grove/South Indy (317) 784-7272 5347 E. Thompson Rd., Indianapolis, 46237 Greenwood • (317) 889-8888 1011 N. State Rd. 135, Greenwood, 46142 papamurphys.com THIS WEEK on the FEATURE TORRY’S TOP TEN WEEKLY MOVIE REVIEW PERRY TWP MARKETPLACE WEB Greenwood moves forward on Beech Grove, Center Grove Thoughts about my Dick Johnson Time for financial $83 million redevelopment PAGE 2 basketball teams advance COVID-19 vaccine Is Dead spring cleaning Page 7 Page 11 Page 13 Page 14 INDEPENDENT LIVING ALTENHEIM | ASPEN TRACE | GREENWOOD HEALTH & LIVING ASSISTED LIVING UNIVERSITY HEIGHTS HEALTH & LIVING REHABILITATION LONG TERM CARE of CarDon MEMORY SUPPORT The heart WWW.CARDON.US Take our free healthcare assessment at cardon.us/sst 2 Week of March 11-17, 2021 • ss-times.com COMMUNITY The Southside Times ON CAMPUS THIS Southside students named to Manchester Univ. Dean’s List WEEK on the Contact the Editorial Consultant Undergraduates – WEB At the end of each semes- Have any news tips? Want to submit a ter, the Office of Academic Affairs publishes calendar event? Have a photograph to the Dean's List. -

2021 Spring Edition

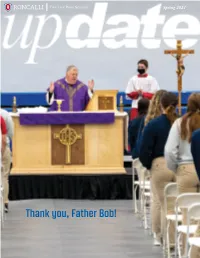

Spring 2021 Thank you, Father Bob! SPRING UPDATE 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 10 PERSPECTIVE 12 SHOW CHOIR 13 VALEDICTORIAN & SALUTATORIAN Garcia Receives Point of View National Merit Finalist 04 11 17 Abe Lincoln Award 06 Revelations 14 ACT Super Stars 18 Lenten Projects 08 Advancement Angle 14 Speech Team to State 20 Scholastic Awards Christmas Kegerreis Silver 09 Performances 16 Senior Assist Day 22 Anniversary Team UPDATE MAGAZINE SPRING 2021 Update Magazine is published by the Office of Institutional Advancement under the direction of Terese R. Carson, Vice President for Institutional Advancement. Its intent is to be a vehicle to inform alumni, family and friends of recent and upcoming happenings and achievements at the school, as well as showcase the talents and gifts of its students, faculty and alumni. Editor-in-Chief: Terese Carson | Deputy Editors: Jeen Endris, Tina Hayes and Gary Armbruster R’81 | Design Director: Jeen Endris | Photographers: John Smith, Stefan Welsh, Phil Anderson, Jeen Endris | Inquiries/Correspondence: Fran Davey, Roncalli High School, 3300 Prague Road, Indianapolis, IN 46227, (317) 787-8277 ext. 238 [email protected]. Website: www.roncalli.org Circulation: 13,037 Email: [email protected] FOR EDITORIAL INFORMATION, CONTACT TERESE CARSON AT (317) 787-8277, EXT. 240 OR [email protected] MISSION STATEMENT As a Catholic high school, our pledge is to provide, in concert with parents, parish and community, an educational opportunity which seeks to form Christian leaders in body, mind and spirit. Guided by prayer and the Gospel values of faith, love and justice, students are challenged to respond to the call of discipleship and to fulfill their potential as lifelong learners in service to others. -

Lag9zpkv-Duran-Duran.Pdf

8CWEZO97UWGN \ Kindle Duran Duran Duran Duran Filesize: 6.13 MB Reviews This book might be worth a study, and superior to other. It can be writter in easy words and phrases and never confusing. I am just happy to inform you that here is the greatest ebook i have got read within my personal daily life and may be he best pdf for actually. (Mrs. Avis Little DDS) DISCLAIMER | DMCA UW0KHPHUUJKU « Book // Duran Duran DURAN DURAN To read Duran Duran PDF, you should click the button listed below and download the document or get access to additional information which might be relevant to DURAN DURAN book. Reference Series Books LLC Dez 2011, 2011. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 246x189x5 mm. This item is printed on demand - Print on Demand Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 90. Chapters: Arcadia songs, Duran Duran albums, Duran Duran members, Duran Duran songs, Duran Duran discography, Hungry Like the Wolf, John Taylor, Warren Cuccurullo, Perfect Day, Lay Lady Lay, Rio, Andy Taylor, All You Need Is Now, Make Me Smile, Notorious, Simon Le Bon, Red Carpet Massacre, Girls on Film, Stephen Duy, Big Thing, Seven and the Ragged Tiger, Ordinary World, Astronaut, Power Station, Nick Rhodes, A View to a Kill, The Reflex, Thank You, Come Undone, The Chauffeur, Carnival, The Wild Boys, Save a Prayer, Medazzaland, Pop Trash, All You Need Is Now Tour, Do You Believe in Shame , Is There Something I Should Know , My Own Way, Electric Barbarella, Skin Trade, Arena, Roger Taylor, All She Wants Is, Planet Earth, Violence of Summer, Liberty, (Reach Up for The)