January – March 2016 Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May 2016 Suzanne Burgess

May 2016 Suzanne Burgess Saving the small things that run the planet Summary The John Muir Way, opened in 2014, stretches 134 miles through nine local authority areas including West Lothian. This B-lines project, the first in Scotland, has identified new opportunities for grassland habitat creation, enhancement and management along the route of the John Muir Way as it passes through the north of West Lothian as well as 1.86 miles either side of this. Through this mapping exercise a number of sites have been identified including 7 schools and nurseries; 3 care homes; 8 places of worship and cemeteries; 2 historic landmarks and buildings; and 1 train station. Additionally, 3 golf courses (73.8 ha), 9 public parks and play spaces (267.81 ha) and 1 country park (369 ha) were identified. There are a number of sites within this project that have nature conservation designations, including 23 Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (496.37 ha) and 5 Sites of Special Scientific Interest (84.13 ha). A further 2 sites have previously been identified as having an Open Mosaic of Habitat on Previously Developed Land with a total of 34.7 ha. By mapping new opportunities this will aid in the future development of projects that will provide real benefits to our declining populations of pollinating insects of bees, wasps, hoverflies and butterflies as well as other wildlife that these habitats support. 1 Contents Page Page Number 1. Introduction 3 1.1 B-lines 3 2. Method 4 3. Results 4 4. Discussion 8 4.1 Schools 8 4.2 Care Homes 9 4.3 Places of Worship and Cemeteries 9 4.4 Historic Landmarks and Buildings 10 4.5 Train Stations 10 4.6 Golf Courses 10 4.7 Public Parks and Play Spaces 11 4.8 Country Parks 12 4.9 Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation 12 4.10 Sites of Special Scientific Interest 12 4.11 Open Mosaic Habitat on Previously Developed Land 13 4.12 Other Opportunities 13 5. -

Essays in Urban Economics by Chuhang Yin Geissler

Essays in Urban Economics by Chuhang Yin Geissler Department of Economics Duke University Date: Approved: Christopher Timmins, Advisor Yi (Daniel) Xu Vincent Joseph Hotz Patrick Bayer Arnaud Maurel Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Economics in the Graduate School of Duke University 2020 ABSTRACT Essays in Urban Economics by Chuhang Yin Geissler Department of Economics Duke University Date: Approved: Christopher Timmins, Advisor Yi (Daniel) Xu Vincent Joseph Hotz Patrick Bayer Arnaud Maurel An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Economics in the Graduate School of Duke University 2020 Copyright c 2020 by Chuhang Yin Geissler All rights reserved Abstract Preference heterogeneity is a driving force in the evolution of urban landscape. Combined with historical conditions, it can perpetuate existing inequality through residential sorting. This dissertation contributes to the literature in residential sorting and hedonic valuation to understand how preference heterogeneity affects location decisions and social welfare. In chapter 2, I estimate the hedonic prices of particulate matter and nitrogen oxide using panel data from Glasgow, Scotland under a variety of functional form assumptions. I find that housing prices are the most elastic with respect to PM2:5 and the least elastic with respect to NOx. The hedonic price for all pollutants decreased from 2001 to 2011. At the median pollutant level, housing price elasticity of PM2:5, PM10, and NOx are -0.2 to -0.46, -0.17 to -0.48, and -0.05 to -0.3 respectively. -

Three Priests Ordained for the Diocese of Oakland

The Catholic Voice is on Facebook VOL. 57, NO. 11 DIOCESE OF OAKLAND JUNE 10, 2019 www.catholicvoiceoakland.org Serving the East Bay Catholic Community since 1963 Copyright 2019 Three priests ordained for the Diocese of Oakland By Michele Jurich Staff writer Addressing the three men before him, “Soon-to-be Father Mark, Father John and Father Javier,” Bishop Michael C. Barber, SJ, told them, “you are called and chosen” and told them what serving means today. In front of a crowded Cathedral of Christ the Light Bishop Barber told them he was zeroing in on the third vow they would take shortly, to celebrate the Mass and administer the Sacrament of Confession worthily. “You will never violate the Seal of Confession,” Bishop Barber told the three new priests. “No state or government can oblige you to betray your penitents.” Legislation — SB 360 — has passed the state Senate and is moving to the Assembly. It will compel a priest to reveal to police some sins he hears in confession. The new priests, John Anthony Pietruszka, 32, Javier Ramirez, 43, and Mark Ruiz, 56, listened attentively. Father Pietruszka is from Fall River Massachusetts; Father Ramirez from Culiacán, Sinaloa, Mexico; and Mark Father Ruiz was born and raised in Oakland. They would not be alone, the bishop assured them. To show that support, more than 70 VOICE CATHOLIC PACCIORINI/THE C. ALBERT priests, mostly diocesan, were present to With Bishop Michael C. Barber, SJ, at left, the trio of men prostrate themselves at the altar. This symbolizes each man’s offer blessings and the sign of peace to unworthiness for the office to be assumed and his dependence upon God and the prayers of the Christian community. -

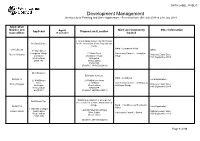

Development Management Weekly List of Planning and Other Applications - Received from 15Th July 2019 to 21St July 2019

DATA LABEL: PUBLIC Development Management Weekly List of Planning and Other Applications - Received from 15th July 2019 to 21st July 2019 Application Number and Ward and Community Other Information Applicant Agent Proposal and Location Case officer (if applicable) Council Listed building consent for alterations Mr Gary Corbett for the conversion of two flats into one house . Ward :- Livingston North 0381/LBC/19 Other 11 Main Street Livingston Village 11 Main Street Community Council :- Livingston Steven McLaren Statutory Expiry Date: Livingston Livingston Village Village 16th September 2019 West Lothian Livingston EH54 7AF West Lothian EH54 7AF (Grid Ref: 303835,666892) Mr A McLaren Extension to house. Ward :- Linlithgow 0408/H/19 Local Application 27 Kettil'stoun 27 Kettil'stoun Grove Grove Linlithgow Community Council :- Linlithgow & Nancy Douglas Statutory Expiry Date: Linlithgow West Lothian Linlithgow Bridge 14th September 2019 West Lothian EH49 6PP EH49 6PP (Grid Ref: 298996,676214) Planning permission in principle for Mr Richard Rae the erection of a house and detached garage. Ward :- Fauldhouse & The Breich 0425/P/19 Local Application Valley 1 Pateshill Cottages Land At Pateshill Cottages Gillian Cyphus West Calder Statutory Expiry Date: West Calder Community Council :- Breich West Lothian 15th September 2019 West Lothian EH55 8NS (Grid Ref: 298458,660284) Page 1 of 10 Shiraz Riaz Installation of UPVC windows, Mr Steven Bull Everest Limited replacement door and formation of decking. 0601/H/19 Everest House Ward :- Armadale & Blackridge Local Application 12 Craigs Court Sopers Road 12 Craigs Court Nancy Douglas Torphichen Cuffley Community Council :- Torphichen Statutory Expiry Date: Torphichen West Lothian Potters Bar 18th September 2019 West Lothian EH48 4NU Hertfordshire EH48 4NU EN6 4SG (Grid Ref: 297047,672165) Mr Steven McMillan Installation of a 7m high amateur radio mast (in retrospect). -

Public Health Information News Issue 1 2011

Public Health Information Service News Issue 1 2011 Public Health Information Service News Issue 1 2011 CONTENTS Updates and Publications ___________________________________________________ 3 Health Challenge Wales Update _____________________________________________ 13 Welsh Assembly Government Health Website Latest Information____________________ 15 Welsh Assembly Government Current Consultations _____________________________ 16 Public Health News Around Wales ___________________________________________ 18 Web Reports and Publications_______________________________________________ 27 Calls for abstracts, awards and courses _______________________________________ 37 Consumer and patients information ___________________________________________ 40 Conference feedback______________________________________________________ 42 Information and Library Services _____________________________________________ 43 Contact details on this page only to save paper and reduce production costs. Sarah Davies, Senior Library Assistant Health Promotion Library Freepost CF2429 Cardiff CF14 5GZ Telephone: 029 2068 1239 Fax: 029 2068 1381 Minicom: 029 2068 1357 Email: [email protected] Public Health Information News is available in Welsh, large print, on disk and Braille. If you want a copy in any of these formats or languages, or you have any other specific requirements please contact Sarah Davies. It is also available electronically on the web at www.wales.gov.uk/healthpromotionlibrary This issue of the newsletter is published on 31 March 2011 2 Public Health Information Service News Issue 1 2011 Welcome to the first issue of Public Health News, published in time for spring and hopefully some spring sunshine. We are continuing with our usual Remember, no item is too small to columns in the news, and based on include, and if you have any the positive responses we have queries about copy simply contact had to our ‘web events’ pages we the editor Sue Thomas at: will only make this information [email protected] available there from now on. -

Final Report of the Green Health Project

GREENHEALTH CONTRIBUTION OF GREEN AND OPEN SPACE TO PUBLIC HEALTH AND WELLBEING Project No. MLU/ECA/UGW/847/08 Final Report For: Rural and Environmental Science and Analytical Services Division Scottish Government James Hutton Institute, OPENSpace Edinburgh University, University of Glasgow, Heriot-Watt University, Biomathematics and Statistics Scotland February 2014 1 The Final Report for GreenHealth has been written and edited by the following individuals: David Miller Jane Morrice Peter Aspinall Mark Brewer Katrina Brown Roger Cummins Rachel Dilley Liz Dinnie Gillian Donaldson-Selby Alana Gilbert Alison Hester Paula Harthill Richard Mitchell Sue Morris Imogen Pearce Lynette Robertson Jenny Roe Catharine Ward Thompson Chen Wang 2 Partner Organisations 1. James Hutton Institute, Craigiebuckler, Aberdeen AB15 8QH Tel: 01224 395000 Email: [email protected] 2. OPENSpace Research Centre, Edinburgh School of Architecture & Landscape Architecture (ESALA), University of Edinburgh, 74 Lauriston Place, Edinburgh EH3 9DF Tel: 0131 221 6177 Email: [email protected] 3. University of Glasgow, 1 Lilybank Gardens, Glasgow G12 8RZ Tel: 0141 330 4039 Email: [email protected] 4. Heriot-Watt University, School of the Built Environment, Edinburgh EH4 4AS Tel: 0131 451 4629 Email: [email protected] Sub-contractor Professor Peter Aspinall, Heriot Watt University, c/o Edinburgh School of Architecture & Landscape Architecture (ESALA), 74 Lauriston Place, Edinburgh EH3 9DF. Email: [email protected] Consultant Dr Mark Brewer, Biomathematics and Statistics Scotland (BioSS), James Hutton Institute, Craigiebuckler, Aberdeen, AB15 8QH Tel: 01224 395125 Email: [email protected] 3 Table of Contents 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... -

Open Space Strategy Consultative Draft

GLASGOW OPEN SPACE STRATEGY CONSULTATIVE DRAFT Prepared For: GLASGOW CITY COUNCIL Issue No 49365601 /05 49365601 /05 49365601 /05 Contents 1. Executive Summary 1 2. Glasgu: The Dear Green Place 11 3. What should open space be used for? 13 4. What is the current open space resource? 23 5. Place Setting for improved economic and community vitality 35 6. Health and wellbeing 59 7. Creating connections 73 8. Ecological Quality 83 9. Enhancing natural processes and generating resources 93 10. Micro‐Climate Control 119 11. Moving towards delivery 123 Strategic Environmental Assessment Interim Environment Report 131 Appendix 144 49365601 /05 49365601 /05 1. Executive Summary The City of Glasgow has a long tradition in the pursuit of a high quality built environment and public realm, continuing to the present day. This strategy represents the next steps in this tradition by setting out how open space should be planned, created, enhanced and managed in order to meet the priorities for Glasgow for the 21st century. This is not just an open space strategy. It is a cross‐cutting vision for delivering a high quality environment that supports economic vitality, improves the health of Glasgow’s residents, provides opportunities for low carbon movement, builds resilience to climate change, supports ecological networks and encourages community cohesion. This is because, when planned well, open space can provide multiple functions that deliver numerous social, economic and environmental benefits. Realising these benefits should be undertaken in a way that is tailored to the needs of the City. As such, this strategy examines the priorities Glasgow has set out and identifies six cross‐cutting strategic priority themes for how open space can contribute to meeting them. -

The Consuming City: Economic Stratification and the Glasgow Effect Katherine Trebeck, Oxfam, UK Kathy Hamilton, University of Strathclyde, UK

ASSOCIATION FOR CONSUMER RESEARCH Labovitz School of Business & Economics, University of Minnesota Duluth, 11 E. Superior Street, Suite 210, Duluth, MN 55802 The Consuming City: Economic Stratification and the Glasgow Effect Katherine Trebeck, Oxfam, UK Kathy Hamilton, University of Strathclyde, UK The development of consumer culture in Glasgow, Scotland has been a central strategy in response to the identity crisis caused by de- industrialisation. We consider whether regeneration strategies that centre on consumption are effective or whether they are they counter-productive and instead harming the social assets of citizens. [to cite]: Katherine Trebeck and Kathy Hamilton (2013) ,"The Consuming City: Economic Stratification and the Glasgow Effect", in NA - Advances in Consumer Research Volume 41, eds. Simona Botti and Aparna Labroo, Duluth, MN : Association for Consumer Research. [url]: http://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/1015040/volumes/v41/NA-41 [copyright notice]: This work is copyrighted by The Association for Consumer Research. For permission to copy or use this work in whole or in part, please contact the Copyright Clearance Center at http://www.copyright.com/. A Play for Power: Exploring the Ways Consumption Marks Social Stratifications Chairs: Laurel Steinfield, University of Oxford, UK Linda Scott, University of Oxford, UK Paper #1: Effects of Geographic and Religious Stratification pejorative labels that limit the consumption choices that can be made and Modernity in the Arab Gulf by women and observe the flow of these ideologies to urban areas. Russell Belk, York University, Canada Kathy Hamilton and Katherine Trebeck close with a presentation Rana Sobh, Qatar University, Qatar that demonstrates how economic stratifications are intensified by regeneration strategies. -

Winchburgh Village, a the Winchburgh Masterplan Includes Plans for Either Two Or Three Select Development of 3, 4 and 5 Bedroom Homes in a Superb Location

Wi nchburgh Vil lage A stylish development of 3, 4 & 5 bedroom homes in West Lothian A reputation you can rely on When it comes to buying your new home it is reassuring to Today Bellway is one of Britain’s largest house building know that you are dealing with one of the most successful companies and is continuing to grow throughout the companies in the country, with a reputation built on country. Since its formation, Bellway has built and sold over designing and creating fine houses and apartments 100,000 homes catering for first time buyers to more nationwide backed up with one of the industry’s best seasoned home buyers and their families. The Group’s after-care services. rapid growth has turned Bellway into a multi-million pound company, employing over 2,000 people directly and many In 1946 John and Russell Bell, newly demobbed, more sub-contractors. From its original base in Newcastle joined their father John T. Bell in a small family owned upon Tyne the Group has expanded in to all regions of the housebuilding business in Newcastle upon Tyne. From the country and is now poised for further growth. very beginning John T. Bell & Sons, as the new company was called, were determined to break the mould. In the Our homes are designed, built and marketed by local early 1950s Kenneth Bell joined his brothers in the teams operating from regional offices managed and company and new approaches to design layout and staffed by local people. This allows the company to stay finishes were developed. -

The Mineral Resources of the Lothians

The mineral resources of the Lothians Information Services Internal Report IR/04/017 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY INTERNAL REPORT IR/04/017 The mineral resources of the Lothians by A.G. MacGregor Selected documents from the BGS Archives No. 11. Formerly issued as Wartime pamphlet No. 45 in 1945. The original typescript was keyed by Jan Fraser, selected, edited and produced by R.P. McIntosh. The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Ordnance Survey licence number GD 272191/1999 Key words Scotland Mineral Resources Lothians . Bibliographical reference MacGregor, A.G. The mineral resources of the Lothians BGS INTERNAL REPORT IR/04/017 . © NERC 2004 Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 2004 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of Survey publications is available from the BGS Keyworth, Nottingham NG12 5GG Sales Desks at Nottingham and Edinburgh; see contact details 0115-936 3241 Fax 0115-936 3488 below or shop online at www.thebgs.co.uk e-mail: [email protected] The London Information Office maintains a reference collection www.bgs.ac.uk of BGS publications including maps for consultation. Shop online at: www.thebgs.co.uk The Survey publishes an annual catalogue of its maps and other publications; this catalogue is available from any of the BGS Sales Murchison House, West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA Desks. 0131-667 1000 Fax 0131-668 2683 The British Geological Survey carries out the geological survey of e-mail: [email protected] Great Britain and Northern Ireland (the latter as an agency service for the government of Northern Ireland), and of the London Information Office at the Natural History Museum surrounding continental shelf, as well as its basic research (Earth Galleries), Exhibition Road, South Kensington, London projects. -

The Scottish Health Survey: Topic Report: the Glasgow Effect

The Scottish Health Survey To p i c The Glasgow Effect Report A National Statistics Publication for Scotland The Scottish Health Survey Topic The Glasgow Effect Report The Scottish Government, Edinburgh 2010 Authors: Rebecca Landy1, David Walsh2, Julie Ramsay3 1 Economic and Social Research Council intern, based with Scottish Government 2 Glasgow Centre for Population Health 3 Scottish Government © Crown copyright 2010 ISBN: 978-0-7559-9741-1 ISSN: 2042-1613 The Scottish Government St Andrew’s House Edinburgh EH1 3DG Produced for the Scottish Government by APS Group Scotland DPPAS10908 Published by the Scottish Government, November 2010 CONTENTS List of Tables 4 Authors’ Acknowledgements 5 Summary 6 1. INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY 7 1.1 Introduction 7 1.2 Aims 8 1.3 Methodology 9 2. MENTAL AND GENERAL HEALTH 12 2.1 Introduction 13 2.2 Mental Health 13 2.2.1 Anxiety 13 2.2.2 General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) 14 2.2.3 WEMWBS 16 2.2.4 Depression 16 2.3 General Health 17 2.3.1 Self-assessed health 17 2.4 Assessing the impact of the socio-economic variables individually 17 2.5 Conclusions and Discussion 17 3. PHYSICAL HEALTH 23 3.1 Introduction 23 3.2 Heart attack 24 3.3 Longstanding limiting illness 25 3.4 Stroke 25 3.5 Cardiovascular disease (CVD) 25 3.6 Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) 26 3.7 Assessing the impact of the socio-economic variables individually 26 3.8 Conclusions and Discussion 26 3.9 Tables 29 4. ADVERSE HEALTH BEHAVIOURS 31 4.1 Introduction 32 4.2 Weight 33 4.2.1 Overweight 33 4.2.2 Obesity 34 4.3 Alcohol Consumption 35 4.3.1 Binge drinking 35 4.3.2 Drinking over the recommended weekly alcohol limit 35 4.3.3 Potential problem drinking 35 4.4 Smoking 36 4.4.1 Current smoking status 36 4.4.2 Heavy smokers 36 4.5 Fruit and vegetable consumption 36 4.6 Assessing the impact of the socio-economic variables individually 37 4.7 Conclusions and Discussion 37 5. -

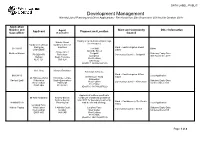

Development Management Weekly List of Planning and Other Applications - Received from 30Th September 2019 to 6Th October 2019

DATA LABEL: PUBLIC Development Management Weekly List of Planning and Other Applications - Received from 30th September 2019 to 6th October 2019 Application Number and Ward and Community Other Information Applicant Agent Proposal and Location Case officer (if applicable) Council Display of an illuminated fascia sign Natalie Gaunt (in retrospect). Cardtronics UK Ltd, Cardtronic Service trading as Solutions Ward :- East Livingston & East 0877/A/19 The Mall Other CASHZONE Calder Adelaide Street 0 Hope Street Matthew Watson Craigshill Statutory Expiry Date: PO BOX 476 Rotherham Community Council :- Craigshill Livingston 30th November 2019 Hatfield South Yorkshire West Lothian AL10 1DT S60 1LH EH54 5DZ (Grid Ref: 306586,668165) Ms L Gray Maxwell Davidson Extenison to house. Ward :- East Livingston & East 0880/H/19 Local Application 20 Hillhouse Wynd Calder 20 Hillhouse Wynd 19 Echline Terrace Kirknewton Rachael Lyall Kirknewton South Queensferry Statutory Expiry Date: West Lothian Community Council :- Kirknewton West Lothian Edinburgh 1st December 2019 EH27 8BU EH27 8BU EH30 9XH (Grid Ref: 311789,667322) Approval of matters specified in Mr Allan Middleton Andrew Bennie conditions of planning permission Andrew Bennie 0462/P/17 for boundary treatments, Ward :- Fauldhouse & The Breich 0899/MSC/19 Planning Ltd road details and drainage. Local Application Valley Longford Farm Mahlon Fautua West Calder 3 Abbotts Court Longford Farm Statutory Expiry Date: Community Council :- Breich West Lothian Dullatur West Calder 1st December 2019 EH55 8NS G68 0AP West Lothian EH55 8NS (Grid Ref: 298174,660738) Page 1 of 8 Approval of matters specified in conditions of planning permission G and L Alastair Nicol 0843/P/18 for the erection of 6 Investments EKJN Architects glamping pods, decking/walkway 0909/MSC/19 waste water tank, landscaping and Ward :- Linlithgow Local Application Duntarvie Castle Bryerton House associated works.