Quick Guide to Science Communication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jackson: Choosing a Methodology: Philosophical Underpinning

JACKSON: CHOOSING A METHODOLOGY: PHILOSOPHICAL UNDERPINNING Choosing a Methodology: Philosophical Practitioner Research Underpinning In Higher Education Copyright © 2013 University of Cumbria Vol 7 (1) pages 49-62 Elizabeth Jackson University of Cumbria [email protected] Abstract As a university lecturer, I find that a frequent question raised by Masters students concerns the methodology chosen for research and the rationale required in dissertations. This paper unpicks some of the philosophical coherence that can inform choices to be made regarding methodology and a well-thought out rationale that can add to the rigour of a research project. It considers the conceptual framework for research including the ontological and epistemological perspectives that are pertinent in choosing a methodology and subsequently the methods to be used. The discussion is exemplified using a concrete example of a research project in order to contextualise theory within practice. Key words Ontology; epistemology; positionality; relationality; methodology; method. Introduction This paper arises from work with students writing Masters dissertations who frequently express confusion and doubt about how appropriate methodology is chosen for research. It will be argued here that consideration of philosophical underpinning can be crucial for both shaping research design and for explaining approaches taken in order to support credibility of research outcomes. It is beneficial, within the unique context of the research, for the researcher to carefully -

Six Tips for Teaching Conversation Skills with Visual Strategies

Six Tips for Teaching Conversation Skills with Visual Strategies Six Tips for Teaching Conversation Skills with Visual Strategies Working with Autism Spectrum Disorders & Related Communication & Social Skill Challenges Linda Hodgdon, M.Ed., CCC-SLP Speech-Language Pathologist Consultant for Autism Spectrum Disorders [email protected] Learning effective conversation skills ranks as one of the most significant social abilities that students with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) need to accomplish. Educators and parents list the challenges: “Steve talks too much.” “Shannon doesn’t take her turn.” “Aiden talks when no one is listening.” “Brandon perseverates on inappropriate topics.” “Kim doesn’t respond when people try to communicate with her.” The list goes on and on. Difficulty with conversation prevents these students from successfully taking part in social opportunities. What makes learning conversation skills so difficult? Conversation requires exactly the skills these students have difficulty with, such as: • Attending • Quickly taking in and processing information • Interpreting confusing social cues • Understanding vocabulary • Comprehending abstract language Many of those skills that create skillful conversation are just the ones that are difficult as a result of the core deficits in Autism Spectrum Disorders. Think about it. From the student’s point of view, conversation can be very puzzling. Conversation is dynamic. .fleeting. .changing. .unpredictable. © Linda Hodgdon, 2007 1 All Rights Reserved This article may not be duplicated, -

The Rhetoric of Positivism Versus Interpretivism: a Personal View1

Weber/Editor’s Comments EDITOR’S COMMENTS The Rhetoric of Positivism Versus Interpretivism: A Personal View1 Many years ago I attended a conference on interpretive research in information systems. My goal was to learn more about interpretive research. In my Ph.D. education, I had studied primarily positivist research methods—for example, experiments, surveys, and field studies. I knew little, however, about interpretive methods. I hoped to improve my knowledge of interpretive methods with a view to using them in due course in my research work. A plenary session at the conference was devoted to a panel discussion on improving the acceptance of interpretive methods within the information systems discipline. During the session, a number of speakers criticized positivist research harshly. Many members in the audience also took up the cudgel to denigrate positivist research. If any other positivistic researchers were present at the session beside me, like me they were cowed. None of us dared to rise and speak in defence of positivism. Subsequently, I came to understand better the feelings of frustration and disaffection that many early interpretive researchers in the information systems discipline experienced when they attempted to publish their work. They felt that often their research was evaluated improperly and treated unfairly. They contended that colleagues who lacked knowledge of interpretive research methods controlled most of the journals. As a result, their work was evaluated using criteria attuned to positivism rather than interpretivism. My most-vivid memory of the panel session, however, was my surprise at the way positivism was being characterized by my colleagues in the session. -

A Comprehensive Framework to Reinforce Evidence Synthesis Features in Cloud-Based Systematic Review Tools

applied sciences Article A Comprehensive Framework to Reinforce Evidence Synthesis Features in Cloud-Based Systematic Review Tools Tatiana Person 1,* , Iván Ruiz-Rube 1 , José Miguel Mota 1 , Manuel Jesús Cobo 1 , Alexey Tselykh 2 and Juan Manuel Dodero 1 1 Department of Informatics Engineering, University of Cadiz, 11519 Puerto Real, Spain; [email protected] (I.R.-R.); [email protected] (J.M.M.); [email protected] (M.J.C.); [email protected] (J.M.D.) 2 Department of Information and Analytical Security Systems, Institute of Computer Technologies and Information Security, Southern Federal University, 347922 Taganrog, Russia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Systematic reviews are powerful methods used to determine the state-of-the-art in a given field from existing studies and literature. They are critical but time-consuming in research and decision making for various disciplines. When conducting a review, a large volume of data is usually generated from relevant studies. Computer-based tools are often used to manage such data and to support the systematic review process. This paper describes a comprehensive analysis to gather the required features of a systematic review tool, in order to support the complete evidence synthesis process. We propose a framework, elaborated by consulting experts in different knowledge areas, to evaluate significant features and thus reinforce existing tool capabilities. The framework will be used to enhance the currently available functionality of CloudSERA, a cloud-based systematic review Citation: Person, T.; Ruiz-Rube, I.; Mota, J.M.; Cobo, M.J.; Tselykh, A.; tool focused on Computer Science, to implement evidence-based systematic review processes in Dodero, J.M. -

Fact Sheet: Information and Communication Technology

Fact Sheet: Information and Communication Technology • Approximately one billion youth live in the world today. This means that approximately one person in five is between the age of 15 to 24 years; • The number of youth living in developing countries will grow by 2025, to 89.5%: • Therefore, it is a must to take youth issues into considerations in the ICT development agenda and ICT policies of each country. • For people who live in the 32 countries where broadband is least affordable – most of them UN-designated Least Developed Countries – a fixed broadband subscription costs over half the average monthly income. • For the majority of countries, over half the Internet users log on at least once a day. • There are more ICT users than ever before, with over five billion mobile phone subscriptions worldwide, and more than two billion Internet users Information and communication technologies have become a significant factor in development, having a profound impact on the political, economic and social sectors of many countries. ICTs can be differentiated from more traditional communication means such as telephone, TV, and radio and are used for the creation, storage, use and exchange of information. ICTs enable real time communication amongst people, allowing them immediate access to new information. ICTs play an important role in enhancing dialogue and understanding amongst youth and between the generations. The proliferation of information and communication technologies presents both opportunities and challenges in terms of the social development and inclusion of youth. There is an increasing emphasis on using information and communication technologies in the context of global youth priorities, such as access to education, employment and poverty eradication. -

The State of Inclusive Science Communication: a Landscape Study

The State of Inclusive Science Communication: A Landscape Study Katherine Canfield and Sunshine Menezes Metcalf Institute, University of Rhode Island Graphics by Christine Liu This report was developed for the University of Rhode Island’s Metcalf Institute with generous support from The Kavli Foundation. Cite as: Canfield, K. & Menezes, S. 2020. The State of Inclusive Science Communication: A Landscape Study. Metcalf Institute, University of Rhode Island. Kingston, RI. 77 pp. Executive Summary Inclusive science communication (ISC) is a new and broad term that encompasses all efforts to engage specific audiences in conversations or activities about science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and medicine (STEMM) topics, including, but not limited to, public engagement, informal science learning, journalism, and formal science education. Unlike other approaches toward science communication, however, ISC research and practice is grounded in inclusion, equity, and intersectionality, making these concerns central to the goals, design, implementation, evaluation, and refinement of science communication efforts. Together, the diverse suite of insights and practices that inform ISC comprise an emerging movement. While there is a growing recognition of the value and urgency of inclusive approaches, there is little documented knowledge about the potential catalysts and barriers for this work. Without documentation, synthesis, and critical reflection, the movement cannot proceed as quickly as is warranted. The University of Rhode Island’s Metcalf -

Climate Change: How Do We Know We're Not Wrong? Naomi Oreskes

Changing Planet: Past, Present, Future Lecture 4 – Climate Change: How Do We Know We’re Not Wrong? Naomi Oreskes, PhD 1. Start of Lecture Four (0:16) [ANNOUNCER:] From the Howard Hughes Medical Institute...The 2012 Holiday Lectures on Science. This year's lectures: "Changing Planet: Past, Present, Future," will be given by Dr. Andrew Knoll, Professor of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University; Dr. Naomi Oreskes, Professor of History and Science Studies at the University of California, San Diego; and Dr. Daniel Schrag, Professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Harvard University. The fourth lecture is titled: Climate Change: How Do We Know We're Not Wrong? And now, a brief video to introduce our lecturer Dr. Naomi Oreskes. 2. Profile of Dr. Naomi Oreskes (1:14) [DR. ORESKES:] One thing that's really important for all people to understand is that the whole notion of certainty is mistaken, and it's something that climate skeptics and deniers and the opponents of evolution really exploit. Many of us think that scientific knowledge is certain, so therefore if someone comes along and points out the uncertainties in a certain scientific body of knowledge, we think that undermines the science, we think that means that there's a problem in the science, and so part of my message is to say that that view of science is incorrect, that the reality of science is that it's always uncertain because if we're actually doing research, it means that we're asking questions, and if we're asking questions, then by definition we're asking questions about things we don't already know about, so uncertainty is part of the lifeblood of science, it's something we need to embrace and realize it's a good thing, not a bad thing. -

PDF Download Starting with Science Strategies for Introducing Young Children to Inquiry 1St Edition Ebook

STARTING WITH SCIENCE STRATEGIES FOR INTRODUCING YOUNG CHILDREN TO INQUIRY 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Marcia Talhelm Edson | 9781571108074 | | | | | Starting with Science Strategies for Introducing Young Children to Inquiry 1st edition PDF Book The presentation of the material is as good as the material utilizing star trek analogies, ancient wisdom and literature and so much more. Using Multivariate Statistics. Michael Gramling examines the impact of policy on practice in early childhood education. Part of a series on. Schauble and colleagues , for example, found that fifth grade students designed better experiments after instruction about the purpose of experimentation. For example, some suggest that learning about NoS enables children to understand the tentative and developmental NoS and science as a human activity, which makes science more interesting for children to learn Abd-El-Khalick a ; Driver et al. Research on teaching and learning of nature of science. The authors begin with theory in a cultural context as a foundation. What makes professional development effective? Frequently, the term NoS is utilised when considering matters about science. This book is a documentary account of a young intern who worked in the Reggio system in Italy and how she brought this pedagogy home to her school in St. Taking Science to School answers such questions as:. The content of the inquiries in science in the professional development programme was based on the different strands of the primary science curriculum, namely Living Things, Energy and Forces, Materials and Environmental Awareness and Care DES Exit interview. Begin to address the necessity of understanding other usually peer positions before they can discuss or comment on those positions. -

Chapter 3 Information and Communication Technology and Its

3. INFORMATIONANDCOMMUNICATIONTECHNOLOGYANDITSIMPACTONTHEECONOMY – 51 Chapter 3 Information and communication technology and its impact on the economy This chapter examines the evolution over time of information and communication technology (ICT), including emerging and possible future developments. It then provides a conceptual overview, highlighting interactions between various layers of information and communication technology. The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law. ADDRESSING THE TAX CHALLENGES OF THE DIGITAL ECONOMY © OECD 2014 52 – 3. INFORMATIONANDCOMMUNICATIONTECHNOLOGYANDITSIMPACTONTHEECONOMY 3.1 The evolution of information and communication technology The development of ICT has been characterised by rapid technological progress that has brought prices of ICT products down rapidly, ensuring that technology can be applied throughout the economy at low cost. In many cases, the drop in prices caused by advances in technology and the pressure for constant innovation have been bolstered by a constant cycle of commoditisation that has affected many of the key technologies that have led to the growth of the digital economy. As products become successful and reach a greater market, their features have a tendency to solidify, making it more difficult for original producers to change those features easily. When features become more stable, it becomes easier for products to be copied by competitors. This is stimulated further by the process of standardisation that is characteristic of the ICT sector, which makes components interoperable, making it more difficult for individual producers to distinguish their products from others. -

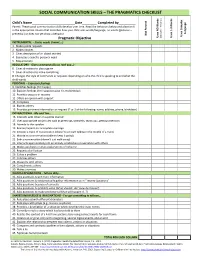

Social Communication Skills – the Pragmatics Checklist

SOCIAL COMMUNICATION SKILLS – THE PRAGMATICS CHECKLIST Child’s Name Date .Completed by . Words Preverbal) Parent: These social communication skills develop over time. Read the behaviors below and place an X - 3 in the appropriate column that describes how your child uses words/language, no words (gestures – - Language preverbal) or does not yet show a behavior. Present Not Uses Complex Uses Complex Gestures Uses Words NO Uses 1 Pragmatic Objective ( INSTRUMENTAL – States needs (I want….) 1. Makes polite requests 2. Makes choices 3. Gives description of an object wanted 4. Expresses a specific personal need 5. Requests help REGULATORY - Gives commands (Do as I tell you…) 6. Gives directions to play a game 7. Gives directions to make something 8. Changes the style of commands or requests depending on who the child is speaking to and what the child wants PERSONAL – Expresses feelings 9. Identifies feelings (I’m happy.) 10. Explains feelings (I’m happy because it’s my birthday) 11. Provides excuses or reasons 12. Offers an opinion with support 13. Complains 14. Blames others 15. Provides pertinent information on request (2 or 3 of the following: name, address, phone, birthdate) INTERACTIONAL - Me and You… 16. Interacts with others in a polite manner 17. Uses appropriate social rules such as greetings, farewells, thank you, getting attention 18. Attends to the speaker 19. Revises/repairs an incomplete message 20. Initiates a topic of conversation (doesn’t just start talking in the middle of a topic) 21. Maintains a conversation (able to keep it going) 22. Ends a conversation (doesn’t just walk away) 23. -

“Hard-Won” Consensus Brent Ranalli

Ranalli • Climate SCienCe, ChaRaCteR, and the “haRd-Won” ConSenSuS Brent Ranalli Climate Science, Character, and the “Hard-Won” Consensus ABSTRACT: What makes a consensus among scientists credible and convincing? This paper introduces the notion of a “hard-won” consensus and uses examples from recent debates over climate change science to show that this heuristic stan- dard for evaluating the quality of a consensus is widely shared. The extent to which a consensus is “hard won” can be understood to depend on the personal qualities of the participating experts; the article demonstrates the continuing util- ity of the norms of modern science introduced by Robert K. Merton by showing that individuals on both sides of the climate science debate rely intuitively on Mertonian ideas—interpreted in terms of character—to frame their arguments. INTRodUCTIoN he late Michael Crichton, science fiction writer and climate con- trarian, once remarked: “Whenever you hear the consensus of Tscientists agrees on something or other, reach for your wallet, because you’re being had. In science consensus is irrelevant. What is relevant is reproducible results” (Crichton 2003). Reproducibility of results and other methodological criteria are indeed the proper basis for scientific judgments. But Crichton is wrong to say that consensus is irrel- evant. Consensus among scientists serves to certify facts for the lay public.1 Those on the periphery of the scientific enterprise (i.e., policy makers and the public), who don’t have the time or the expertise or the equipment to check results for themselves, necessarily rely on the testimony of those at the center. -

Advancing Science Communication.Pdf

SCIENCETreise, Weigold COMMUNICATION / SCIENCE COMMUNICATORS Scholars of science communication have identified many issues that may help to explain why sci- ence communication is not as “effective” as it could be. This article presents results from an exploratory study that consisted of an open-ended survey of science writers, editors, and science communication researchers. Results suggest that practitioners share many issues of concern to scholars. Implications are that a clear agenda for science communication research now exists and that empirical research is needed to improve the practice of communicating science. Advancing Science Communication A Survey of Science Communicators DEBBIE TREISE MICHAEL F. WEIGOLD University of Florida The writings of science communication scholars suggest twodominant themes about science communication: it is important and it is not done well (Hartz and Chappell 1997; Nelkin 1995; Ziman 1992). This article explores the opinions of science communication practitioners with respect to the sec- ond of these themes, specifically, why science communication is often done poorly and how it can be improved. The opinions of these practitioners are important because science communicators serve as a crucial link between the activities of scientists and the public that supports such activities. To intro- duce our study, we first review opinions as to why science communication is important. We then examine the literature dealing with how well science communication is practiced. Authors’Note: We would like to acknowledge NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center for provid- ing the funds todothis research. We alsowant tothank Rick Borcheltforhis help with the collec - tion of data. Address correspondence to Debbie Treise, University of Florida, College of Journalism and Communications, P.O.