The Rhetoric of Positivism Versus Interpretivism: a Personal View1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jackson: Choosing a Methodology: Philosophical Underpinning

JACKSON: CHOOSING A METHODOLOGY: PHILOSOPHICAL UNDERPINNING Choosing a Methodology: Philosophical Practitioner Research Underpinning In Higher Education Copyright © 2013 University of Cumbria Vol 7 (1) pages 49-62 Elizabeth Jackson University of Cumbria [email protected] Abstract As a university lecturer, I find that a frequent question raised by Masters students concerns the methodology chosen for research and the rationale required in dissertations. This paper unpicks some of the philosophical coherence that can inform choices to be made regarding methodology and a well-thought out rationale that can add to the rigour of a research project. It considers the conceptual framework for research including the ontological and epistemological perspectives that are pertinent in choosing a methodology and subsequently the methods to be used. The discussion is exemplified using a concrete example of a research project in order to contextualise theory within practice. Key words Ontology; epistemology; positionality; relationality; methodology; method. Introduction This paper arises from work with students writing Masters dissertations who frequently express confusion and doubt about how appropriate methodology is chosen for research. It will be argued here that consideration of philosophical underpinning can be crucial for both shaping research design and for explaining approaches taken in order to support credibility of research outcomes. It is beneficial, within the unique context of the research, for the researcher to carefully -

The Philosophical Underpinnings of Educational Research

The Philosophical Underpinnings of Educational Research Lindsay Mack Abstract This article traces the underlying theoretical framework of educational research. It outlines the definitions of epistemology, ontology and paradigm and the origins, main tenets, and key thinkers of the 3 paradigms; positivist, interpetivist and critical. By closely analyzing each paradigm, the literature review focuses on the ontological and epistemological assumptions of each paradigm. Finally the author analyzes not only the paradigm’s weakness but also the author’s own construct of reality and knowledge which align with the critical paradigm. Key terms: Paradigm, Ontology, Epistemology, Positivism, Interpretivism The English Language Teaching (ELT) field has moved from an ad hoc field with amateurish research to a much more serious enterprise of professionalism. More teachers are conducting research to not only inform their teaching in the classroom but also to bridge the gap between the external researcher dictating policy and the teacher negotiating that policy with the practical demands of their classroom. I was a layperson, not an educational researcher. Determined to emancipate myself from my layperson identity, I began to analyze the different philosophical underpinnings of each paradigm, reading about the great thinkers’ theories and the evolution of social science research. Through this process I began to examine how I view the world, thus realizing my own construction of knowledge and social reality, which is actually quite loose and chaotic. Most importantly, I realized that I identify most with the critical paradigm assumptions and that my future desired role as an educational researcher is to affect change and challenge dominant social and political discourses in ELT. -

A Comprehensive Framework to Reinforce Evidence Synthesis Features in Cloud-Based Systematic Review Tools

applied sciences Article A Comprehensive Framework to Reinforce Evidence Synthesis Features in Cloud-Based Systematic Review Tools Tatiana Person 1,* , Iván Ruiz-Rube 1 , José Miguel Mota 1 , Manuel Jesús Cobo 1 , Alexey Tselykh 2 and Juan Manuel Dodero 1 1 Department of Informatics Engineering, University of Cadiz, 11519 Puerto Real, Spain; [email protected] (I.R.-R.); [email protected] (J.M.M.); [email protected] (M.J.C.); [email protected] (J.M.D.) 2 Department of Information and Analytical Security Systems, Institute of Computer Technologies and Information Security, Southern Federal University, 347922 Taganrog, Russia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Systematic reviews are powerful methods used to determine the state-of-the-art in a given field from existing studies and literature. They are critical but time-consuming in research and decision making for various disciplines. When conducting a review, a large volume of data is usually generated from relevant studies. Computer-based tools are often used to manage such data and to support the systematic review process. This paper describes a comprehensive analysis to gather the required features of a systematic review tool, in order to support the complete evidence synthesis process. We propose a framework, elaborated by consulting experts in different knowledge areas, to evaluate significant features and thus reinforce existing tool capabilities. The framework will be used to enhance the currently available functionality of CloudSERA, a cloud-based systematic review Citation: Person, T.; Ruiz-Rube, I.; Mota, J.M.; Cobo, M.J.; Tselykh, A.; tool focused on Computer Science, to implement evidence-based systematic review processes in Dodero, J.M. -

PDF Download Starting with Science Strategies for Introducing Young Children to Inquiry 1St Edition Ebook

STARTING WITH SCIENCE STRATEGIES FOR INTRODUCING YOUNG CHILDREN TO INQUIRY 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Marcia Talhelm Edson | 9781571108074 | | | | | Starting with Science Strategies for Introducing Young Children to Inquiry 1st edition PDF Book The presentation of the material is as good as the material utilizing star trek analogies, ancient wisdom and literature and so much more. Using Multivariate Statistics. Michael Gramling examines the impact of policy on practice in early childhood education. Part of a series on. Schauble and colleagues , for example, found that fifth grade students designed better experiments after instruction about the purpose of experimentation. For example, some suggest that learning about NoS enables children to understand the tentative and developmental NoS and science as a human activity, which makes science more interesting for children to learn Abd-El-Khalick a ; Driver et al. Research on teaching and learning of nature of science. The authors begin with theory in a cultural context as a foundation. What makes professional development effective? Frequently, the term NoS is utilised when considering matters about science. This book is a documentary account of a young intern who worked in the Reggio system in Italy and how she brought this pedagogy home to her school in St. Taking Science to School answers such questions as:. The content of the inquiries in science in the professional development programme was based on the different strands of the primary science curriculum, namely Living Things, Energy and Forces, Materials and Environmental Awareness and Care DES Exit interview. Begin to address the necessity of understanding other usually peer positions before they can discuss or comment on those positions. -

Principles of Scientific Inquiry

Chapter 2 PRINCIPLES OF SCIENTIFIC INQUIRY Introduction This chapter provides a summary of the principles of scientific inquiry. The purpose is to explain terminology, and introduce concepts, which are explained more completely in later chapters. Much of the content has been based on explanations and examples given by Wilson (1). The Scientific Method Although most of us have heard, at some time in our careers, that research must be carried out according to “the scientific method”, there is no single, scientific method. The term is usually used to mean a systematic approach to solving a problem in science. Three types of investigation, or method, can be recognized: · The Observational Method · The Experimental (and quasi-experimental) Methods, and · The Survey Method. The observational method is most common in the natural sciences, especially in fields such as biology, geology and environmental science. It involves recording observations according to a plan, which prescribes what information to collect, where it should be sought, and how it should be recorded. In the observational method, the researcher does not control any of the variables. In fact, it is important that the research be carried out in such a manner that the investigations do not change the behaviour of what is being observed. Errors introduced as a result of observing a phenomenon are known as systematic errors because they apply to all observations. Once a valid statistical sample (see Chapter Four) of observations has been recorded, the researcher analyzes and interprets the data, and develops a theory or hypothesis, which explains the observations. The experimental method begins with a hypothesis. -

Advancing Science Communication.Pdf

SCIENCETreise, Weigold COMMUNICATION / SCIENCE COMMUNICATORS Scholars of science communication have identified many issues that may help to explain why sci- ence communication is not as “effective” as it could be. This article presents results from an exploratory study that consisted of an open-ended survey of science writers, editors, and science communication researchers. Results suggest that practitioners share many issues of concern to scholars. Implications are that a clear agenda for science communication research now exists and that empirical research is needed to improve the practice of communicating science. Advancing Science Communication A Survey of Science Communicators DEBBIE TREISE MICHAEL F. WEIGOLD University of Florida The writings of science communication scholars suggest twodominant themes about science communication: it is important and it is not done well (Hartz and Chappell 1997; Nelkin 1995; Ziman 1992). This article explores the opinions of science communication practitioners with respect to the sec- ond of these themes, specifically, why science communication is often done poorly and how it can be improved. The opinions of these practitioners are important because science communicators serve as a crucial link between the activities of scientists and the public that supports such activities. To intro- duce our study, we first review opinions as to why science communication is important. We then examine the literature dealing with how well science communication is practiced. Authors’Note: We would like to acknowledge NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center for provid- ing the funds todothis research. We alsowant tothank Rick Borcheltforhis help with the collec - tion of data. Address correspondence to Debbie Treise, University of Florida, College of Journalism and Communications, P.O. -

Logical Empiricism / Positivism Some Empiricist Slogans

4/13/16 Logical empiricism / positivism Some empiricist slogans o Hume’s 18th century book-burning passage Key elements of a logical positivist /empiricist conception of science o Comte’s mid-19th century rejection of n Motivations for post WW1 ‘scientific philosophy’ ‘speculation after first & final causes o viscerally opposed to speculation / mere metaphysics / idealism o Duhem’s late 19th/early 20th century slogan: o a normative demarcation project: to show why science ‘save the phenomena’ is and should be epistemically authoritative n Empiricist commitments o Hempel’s injunction against ‘detours n Logicism through the realm of unobservables’ Conflicts & Memories: The First World War Vienna Circle Maria Marchant o Debussy: Berceuse héroique, Élégie So - what was the motivation for this “revolutionary, written war-time Paris (1914), heralds the ominous bugle call of war uncompromising empricism”? (Godfrey Smith, Ch. 2) o Rachmaninov: Études-Tableaux Op. 39, No 8, 5 “some of the most impassioned, fervent work the composer wrote” Why the “massive intellectual housecleaning”? (Godfrey Smith) o Ireland: Rhapsody, London Nights, London Pieces a “turbulant, virtuosic work… Consider the context: World War I / the interwar period o Prokofiev: Visions Fugitives, Op. 22 written just before he fled as a fugitive himself to the US (1917); military aggression & sardonic irony o Ravel: Le Tombeau de Couperin each of six movements dedicated to a friend who died in the war x Key problem (1): logicism o Are there, in fact, “rules” governing inference -

Philosophical Approaches to Qualitative Research

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons School of Social Work: Faculty Publications and Other Works Faculty Publications 2014 Philosophical Approaches to Qualitative Research Julia Pryce [email protected] Renée Spencer Jill Walsh Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/socialwork_facpubs Part of the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Pryce, Julia; Spencer, Renée; and Walsh, Jill. Philosophical Approaches to Qualitative Research. The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research Methods, , : 81-98, 2014. Retrieved from Loyola eCommons, School of Social Work: Faculty Publications and Other Works, http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/ 9780199811755.001.0001 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Social Work: Faculty Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. © Oxford University Press, 2014. CHAPTER Philosophical Approaches to 5 Qualitative Research Renée Spencer, Julia M. Pryce, and Jill Walsh Abstract This chapter reviews some of the major overarching philosophical approaches to qualitative inquiry and includes some historical background for each. Taking a “big picture” view, the chapter discusses post-positivism, constructivism, critical theory, feminism, and queer theory and offers a brief history of these -

Positivism and the Inseparability of Law and Morals

\\server05\productn\N\NYU\83-4\NYU403.txt unknown Seq: 1 25-SEP-08 12:20 POSITIVISM AND THE INSEPARABILITY OF LAW AND MORALS LESLIE GREEN* H.L.A. Hart made a famous claim that legal positivism somehow involves a “sepa- ration of law and morals.” This Article seeks to clarify and assess this claim, con- tending that Hart’s separability thesis should not be confused with the social thesis, the sources thesis, or a methodological thesis about jurisprudence. In contrast, Hart’s separability thesis denies the existence of any necessary conceptual connec- tions between law and morality. That thesis, however, is false: There are many necessary connections between law and morality, some of them conceptually signif- icant. Among them is an important negative connection: Law is, of its nature, morally fallible and morally risky. Lon Fuller emphasized what he called the “internal morality of law,” the “morality that makes law possible.” This Article argues that Hart’s most important message is that there is also an immorality that law makes possible. Law’s nature is seen not only in its internal virtues, in legality, but also in its internal vices, in legalism. INTRODUCTION H.L.A. Hart’s Holmes Lecture gave new expression to the old idea that legal systems comprise positive law only, a thesis usually labeled “legal positivism.” Hart did this in two ways. First, he disen- tangled the idea from the independent and distracting projects of the imperative theory of law, the analytic study of legal language, and non-cognitivist moral philosophies. Hart’s second move was to offer a fresh characterization of the thesis. -

Introduction to Philosophy of Science

INTRODUCTION TO PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE The aim of philosophy of science is to understand what scientists did and how they did it, where history of science shows that they performed basic research very well. Therefore to achieve this aim, philosophers look back to the great achievements in the evolution of modern science that started with the Copernicus with greater emphasis given to more recent accomplishments. The earliest philosophy of science in the last two hundred years is Romanticism, which started as a humanities discipline and was later adapted to science as a humanities specialty. The Romantics view the aim of science as interpretative understanding, which is a mentalistic ontology acquired by introspection. They call language containing this ontology “theory”. The most successful science sharing in the humanities aim is economics, but since the development of econometrics that enables forecasting and policy, the humanities aim is mixed with the natural science aim of prediction and control. Often, however, econometricians have found that successful forecasting by econometric models must be purchased at the price of rejecting equation specifications based on the interpretative understanding supplied by neoclassical macroeconomic and microeconomic theory. In this context the term “economic theory” means precisely such neoclassical equation specifications. Aside from economics Romanticism has little relevance to the great accomplishments in the history of science, because its concept of the aim of science has severed it from the benefits of the examination of the history of science. The Romantic philosophy of social science is still resolutely practiced in immature sciences such as sociology, where mentalistic description prevails, where quantification and prediction are seldom attempted, and where implementation in social policy is seldom effective and often counterproductive. -

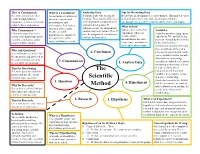

The Scientific Method Is a It Is a Possible Answer and Logical Problem-Solving Explanation to Your Question Process Used by Scientists

How to Communicate What is a Conclusion? Analyzing Data Tips for Recording Data Scientist communicate their A conclusion is a statement Scientists study data to look for Record data in an organized, accurate manner. This makes it easier results through journals, based on experimental meaning. They look for differences to identify patterns/ trends, make predictions, and draw magazines, websites, television, measurements and in the dependent variable between conclusions. Use a scientific journal, tables, charts, and graphs. radio, lectures, and posters. control and test groups. If observations. It includes a What is Data? summary of the results, differences exist, the independent Data are the results of the Variables Why Communicate? whether or not the variable may have had an effect. If Communicating discoveries experiment. They can Variables are what change in an hypothesis was supported, not, the independent variable may advances the knowledge of the include number experiment. The variable being the significance of the not have had any effect. scientific community, and it measurements like time, tested or changed by the scientist study, and future research. improves future studies. temperature, and mass, or is the independent or they can be observations. manipulated variable. Normally, there is only one of these at a Why Ask Questions? time so that experimental results It is important to clearly define 6. Conclusion can be attributed to that variable. the question being answered or Dependent or responding the problem being solved by 7. Communicate variables are what the scientist is the scientific investigation. 5. Analyze Data measuring or observing. If there Tips for Questioning is a direct link between Scientific questions should be The independent and dependent narrow and specific. -

Outdoor Education – Research Summary

Outdoor Education – Research Summary Research on outdoor education is synthesized below. Links to specific research papers and summaries are provided at the bottom. School performance increases when children learn outdoors1 A number of studies have documented increased school performance through outdoor education. Research has document increased standardized test scores, enhanced attitude about school, improved in-school behavior, improved attendance and overall enhanced student achievement when students learn in and about nature. In addition, outdoor education effectively employs a greater range of children’s intelligences. Many researchers contribute the increase in performance to increased relevance and hands-on experience of learning outdoors. Learning outdoors is healthy2 Learning outdoors is active and increases students’ physical, mental and social health. Some studies have even shown follow-up (e.g., non-school) physical activity increases with outdoor learning. Access to nature has also been shown to decrease the symptoms of ADHD. Outdoor learning and access to nature also decrease stress levels of students and teachers. Learning outdoors supports child development3 Children greatly benefit developmentally from being outdoors. Outdoor education and play support emotional, behavioral and intellectual development. Studies have shown that students who learn outdoors develop: a sense of self, independence, confidence, creativity, decision-making and problem-solving skills, empathy towards others, motor skills, self-discipline and initiative. Teaching and learning outdoors is fun4 Often, the outdoors provides a change of pace from the classroom, which students and teachers enjoy. Studies have shown increased student enthusiasm for learning outdoors. Learning outdoors helps develop a sense of place and civic attitudes and behaviors5 Outdoor experiences help students increase their understanding of their natural and human communities which leads to a sense of place.