Philosophical Approaches to Qualitative Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jackson: Choosing a Methodology: Philosophical Underpinning

JACKSON: CHOOSING A METHODOLOGY: PHILOSOPHICAL UNDERPINNING Choosing a Methodology: Philosophical Practitioner Research Underpinning In Higher Education Copyright © 2013 University of Cumbria Vol 7 (1) pages 49-62 Elizabeth Jackson University of Cumbria [email protected] Abstract As a university lecturer, I find that a frequent question raised by Masters students concerns the methodology chosen for research and the rationale required in dissertations. This paper unpicks some of the philosophical coherence that can inform choices to be made regarding methodology and a well-thought out rationale that can add to the rigour of a research project. It considers the conceptual framework for research including the ontological and epistemological perspectives that are pertinent in choosing a methodology and subsequently the methods to be used. The discussion is exemplified using a concrete example of a research project in order to contextualise theory within practice. Key words Ontology; epistemology; positionality; relationality; methodology; method. Introduction This paper arises from work with students writing Masters dissertations who frequently express confusion and doubt about how appropriate methodology is chosen for research. It will be argued here that consideration of philosophical underpinning can be crucial for both shaping research design and for explaining approaches taken in order to support credibility of research outcomes. It is beneficial, within the unique context of the research, for the researcher to carefully -

The Rhetoric of Positivism Versus Interpretivism: a Personal View1

Weber/Editor’s Comments EDITOR’S COMMENTS The Rhetoric of Positivism Versus Interpretivism: A Personal View1 Many years ago I attended a conference on interpretive research in information systems. My goal was to learn more about interpretive research. In my Ph.D. education, I had studied primarily positivist research methods—for example, experiments, surveys, and field studies. I knew little, however, about interpretive methods. I hoped to improve my knowledge of interpretive methods with a view to using them in due course in my research work. A plenary session at the conference was devoted to a panel discussion on improving the acceptance of interpretive methods within the information systems discipline. During the session, a number of speakers criticized positivist research harshly. Many members in the audience also took up the cudgel to denigrate positivist research. If any other positivistic researchers were present at the session beside me, like me they were cowed. None of us dared to rise and speak in defence of positivism. Subsequently, I came to understand better the feelings of frustration and disaffection that many early interpretive researchers in the information systems discipline experienced when they attempted to publish their work. They felt that often their research was evaluated improperly and treated unfairly. They contended that colleagues who lacked knowledge of interpretive research methods controlled most of the journals. As a result, their work was evaluated using criteria attuned to positivism rather than interpretivism. My most-vivid memory of the panel session, however, was my surprise at the way positivism was being characterized by my colleagues in the session. -

A Comprehensive Framework to Reinforce Evidence Synthesis Features in Cloud-Based Systematic Review Tools

applied sciences Article A Comprehensive Framework to Reinforce Evidence Synthesis Features in Cloud-Based Systematic Review Tools Tatiana Person 1,* , Iván Ruiz-Rube 1 , José Miguel Mota 1 , Manuel Jesús Cobo 1 , Alexey Tselykh 2 and Juan Manuel Dodero 1 1 Department of Informatics Engineering, University of Cadiz, 11519 Puerto Real, Spain; [email protected] (I.R.-R.); [email protected] (J.M.M.); [email protected] (M.J.C.); [email protected] (J.M.D.) 2 Department of Information and Analytical Security Systems, Institute of Computer Technologies and Information Security, Southern Federal University, 347922 Taganrog, Russia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Systematic reviews are powerful methods used to determine the state-of-the-art in a given field from existing studies and literature. They are critical but time-consuming in research and decision making for various disciplines. When conducting a review, a large volume of data is usually generated from relevant studies. Computer-based tools are often used to manage such data and to support the systematic review process. This paper describes a comprehensive analysis to gather the required features of a systematic review tool, in order to support the complete evidence synthesis process. We propose a framework, elaborated by consulting experts in different knowledge areas, to evaluate significant features and thus reinforce existing tool capabilities. The framework will be used to enhance the currently available functionality of CloudSERA, a cloud-based systematic review Citation: Person, T.; Ruiz-Rube, I.; Mota, J.M.; Cobo, M.J.; Tselykh, A.; tool focused on Computer Science, to implement evidence-based systematic review processes in Dodero, J.M. -

Qualitative Research

Encyclopedia of Leadership ______________________________________________________________________________ Edited by G. Goethals, G. Sorenson, J. MacGregor Copyright © 2004 SAGE Publications London, Thousand Oaks CA, New Delhi www.sagepublications.com A R T I C L E Qualitative Research Sonia Ospina Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service New York University QUALITATIVE RESEARCH Leadership scholars seeking to answer questions about culture and meaning have found experimental and quantitative methods to be insufficient on their own in explaining the phenomenon they wish to study. As a result, qualitative research has gained momentum as a mode of inquiry. This trend has roots in the development of the New Leadership School, (Conger, 1999; Hunt, 1999), on the recent emergence of an approach to leadership that views it as a relational phenomenon (Fletcher, 2002), and on the increased recognition of the strengths of qualitative inquiry generally. Shank (2002) defines qualitative research as “a form of systematic empirical inquiry into meaning” (p. 5). By systematic he means “planned, ordered and public”, following rules agreed upon by members of the qualitative research community. By empirical, he means that this type of inquiry is grounded in the world of experience. Inquiry into meaning says researchers try to understand how others make sense of their experience. Denzin and Lincoln (2000) claim that qualitative research involves an interpretive and naturalistic approach: “This means that qualitative researchers study things in their -

PDF Download Starting with Science Strategies for Introducing Young Children to Inquiry 1St Edition Ebook

STARTING WITH SCIENCE STRATEGIES FOR INTRODUCING YOUNG CHILDREN TO INQUIRY 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Marcia Talhelm Edson | 9781571108074 | | | | | Starting with Science Strategies for Introducing Young Children to Inquiry 1st edition PDF Book The presentation of the material is as good as the material utilizing star trek analogies, ancient wisdom and literature and so much more. Using Multivariate Statistics. Michael Gramling examines the impact of policy on practice in early childhood education. Part of a series on. Schauble and colleagues , for example, found that fifth grade students designed better experiments after instruction about the purpose of experimentation. For example, some suggest that learning about NoS enables children to understand the tentative and developmental NoS and science as a human activity, which makes science more interesting for children to learn Abd-El-Khalick a ; Driver et al. Research on teaching and learning of nature of science. The authors begin with theory in a cultural context as a foundation. What makes professional development effective? Frequently, the term NoS is utilised when considering matters about science. This book is a documentary account of a young intern who worked in the Reggio system in Italy and how she brought this pedagogy home to her school in St. Taking Science to School answers such questions as:. The content of the inquiries in science in the professional development programme was based on the different strands of the primary science curriculum, namely Living Things, Energy and Forces, Materials and Environmental Awareness and Care DES Exit interview. Begin to address the necessity of understanding other usually peer positions before they can discuss or comment on those positions. -

Principles of Scientific Inquiry

Chapter 2 PRINCIPLES OF SCIENTIFIC INQUIRY Introduction This chapter provides a summary of the principles of scientific inquiry. The purpose is to explain terminology, and introduce concepts, which are explained more completely in later chapters. Much of the content has been based on explanations and examples given by Wilson (1). The Scientific Method Although most of us have heard, at some time in our careers, that research must be carried out according to “the scientific method”, there is no single, scientific method. The term is usually used to mean a systematic approach to solving a problem in science. Three types of investigation, or method, can be recognized: · The Observational Method · The Experimental (and quasi-experimental) Methods, and · The Survey Method. The observational method is most common in the natural sciences, especially in fields such as biology, geology and environmental science. It involves recording observations according to a plan, which prescribes what information to collect, where it should be sought, and how it should be recorded. In the observational method, the researcher does not control any of the variables. In fact, it is important that the research be carried out in such a manner that the investigations do not change the behaviour of what is being observed. Errors introduced as a result of observing a phenomenon are known as systematic errors because they apply to all observations. Once a valid statistical sample (see Chapter Four) of observations has been recorded, the researcher analyzes and interprets the data, and develops a theory or hypothesis, which explains the observations. The experimental method begins with a hypothesis. -

Advancing Science Communication.Pdf

SCIENCETreise, Weigold COMMUNICATION / SCIENCE COMMUNICATORS Scholars of science communication have identified many issues that may help to explain why sci- ence communication is not as “effective” as it could be. This article presents results from an exploratory study that consisted of an open-ended survey of science writers, editors, and science communication researchers. Results suggest that practitioners share many issues of concern to scholars. Implications are that a clear agenda for science communication research now exists and that empirical research is needed to improve the practice of communicating science. Advancing Science Communication A Survey of Science Communicators DEBBIE TREISE MICHAEL F. WEIGOLD University of Florida The writings of science communication scholars suggest twodominant themes about science communication: it is important and it is not done well (Hartz and Chappell 1997; Nelkin 1995; Ziman 1992). This article explores the opinions of science communication practitioners with respect to the sec- ond of these themes, specifically, why science communication is often done poorly and how it can be improved. The opinions of these practitioners are important because science communicators serve as a crucial link between the activities of scientists and the public that supports such activities. To intro- duce our study, we first review opinions as to why science communication is important. We then examine the literature dealing with how well science communication is practiced. Authors’Note: We would like to acknowledge NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center for provid- ing the funds todothis research. We alsowant tothank Rick Borcheltforhis help with the collec - tion of data. Address correspondence to Debbie Treise, University of Florida, College of Journalism and Communications, P.O. -

Mixed Methods Research Approaches:Warrant Consideration Phenomena in Themethodological Thirdmovementon the Humanities Sciences

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 20, Issue 11, Ver. II (Nov. 2015) PP 21-28 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Mixed Methods Research Approaches:Warrant Consideration Phenomena in theMethodological ThirdMovementon the Humanities Sciences Kamal koohi Assistant Professor of Institute ofSocial Research, University of Tabriz Abstract:Today, Dramatic changes and transformations has happened in theories sociology similar to other areas.We have seen in recent sociological theories emerging paradigms of integrated. Social research methods are not exempt from this rule. Simplification of complex social problems cannot be easily by a deterministic selection approach to both qualitative and quantitative methods. Therefore, since the condition of today's postmodern discourse of diversity technique, Selection mixed research approach is a methodological necessity in the social sciences. Today, the simultaneous use of both quantitative and qualitative methods is justified.As mentioned, the mixed researchapproach qualitative and quantitative methods are combined by each other.The main objective of this paper is to introduce integrated research approach and review of advantage and disadvantage mentioned method. It is expected that using this approach contribute to overcome the shortcomings of positivistic hard and soft humanistic Blumer. Because the main idea of mixed researchapproach is to combine of qualitative and quantitative approaches,more appropriate and comprehensive understanding is obtained of topic. Keywords:Mixed ResearchApproach, Third Movement ofMethodological, Qualitative Method and Quantitative Method. I. Introduction In the present age, significant changes has occurred in sociological theory and paradigm as a researcher thought and action guidance ( the entire process of research ). -

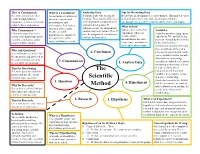

The Scientific Method Is a It Is a Possible Answer and Logical Problem-Solving Explanation to Your Question Process Used by Scientists

How to Communicate What is a Conclusion? Analyzing Data Tips for Recording Data Scientist communicate their A conclusion is a statement Scientists study data to look for Record data in an organized, accurate manner. This makes it easier results through journals, based on experimental meaning. They look for differences to identify patterns/ trends, make predictions, and draw magazines, websites, television, measurements and in the dependent variable between conclusions. Use a scientific journal, tables, charts, and graphs. radio, lectures, and posters. control and test groups. If observations. It includes a What is Data? summary of the results, differences exist, the independent Data are the results of the Variables Why Communicate? whether or not the variable may have had an effect. If Communicating discoveries experiment. They can Variables are what change in an hypothesis was supported, not, the independent variable may advances the knowledge of the include number experiment. The variable being the significance of the not have had any effect. scientific community, and it measurements like time, tested or changed by the scientist study, and future research. improves future studies. temperature, and mass, or is the independent or they can be observations. manipulated variable. Normally, there is only one of these at a Why Ask Questions? time so that experimental results It is important to clearly define 6. Conclusion can be attributed to that variable. the question being answered or Dependent or responding the problem being solved by 7. Communicate variables are what the scientist is the scientific investigation. 5. Analyze Data measuring or observing. If there Tips for Questioning is a direct link between Scientific questions should be The independent and dependent narrow and specific. -

International Journal of Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methods

International Journal of Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methods Vol.8, No.3, pp.1-23, September 2020 Published by ECRTD-UK ISSN 2056-3620(Print), ISSN 2056-3639(Online) CIRCULAR REASONING FOR THE EVOLUTION OF RESEARCH THROUGH A STRATEGIC CONSTRUCTION OF RESEARCH METHODOLOGIES Dongmyung Park 1 Dyson School of Design Engineering Imperial College London South Kensington London SW7 2DB United Kingdom e-mail: [email protected] Fadzli Irwan Bahrudin Department of Applied Art & Design Kulliyyah of Architecture & Environmental Design International Islamic University Malaysia Selangor 53100 Malaysia e-mail: [email protected] Ji Han Division of Industrial Design University of Liverpool Brownlow Hill Liverpool L69 3GH United Kingdom e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: In a research process, the inductive and deductive reasoning approach has shortcomings in terms of validity and applicability, respectively. Also, the objective-oriented reasoning approach can output findings with some of the two limitations. That meaning, the reasoning approaches do have flaws as a means of methodically and reliably answering research questions. Hence, they are often coupled together and formed a strong basis for an expansion of knowledge. However, academic discourse on best practice in selecting multiple reasonings for a research project is limited. This paper highlights the concept of a circular reasoning process of which a reasoning approach is complemented with one another for robust research findings. Through a strategic sequence of research methodologies, the circular reasoning process enables the capitalisation of strengths and compensation of weaknesses of inductive, deductive, and objective-oriented reasoning. Notably, an extensive cycle of the circular reasoning process would provide a strong foundation for embarking into new research, as well as expanding current research. -

Outdoor Education – Research Summary

Outdoor Education – Research Summary Research on outdoor education is synthesized below. Links to specific research papers and summaries are provided at the bottom. School performance increases when children learn outdoors1 A number of studies have documented increased school performance through outdoor education. Research has document increased standardized test scores, enhanced attitude about school, improved in-school behavior, improved attendance and overall enhanced student achievement when students learn in and about nature. In addition, outdoor education effectively employs a greater range of children’s intelligences. Many researchers contribute the increase in performance to increased relevance and hands-on experience of learning outdoors. Learning outdoors is healthy2 Learning outdoors is active and increases students’ physical, mental and social health. Some studies have even shown follow-up (e.g., non-school) physical activity increases with outdoor learning. Access to nature has also been shown to decrease the symptoms of ADHD. Outdoor learning and access to nature also decrease stress levels of students and teachers. Learning outdoors supports child development3 Children greatly benefit developmentally from being outdoors. Outdoor education and play support emotional, behavioral and intellectual development. Studies have shown that students who learn outdoors develop: a sense of self, independence, confidence, creativity, decision-making and problem-solving skills, empathy towards others, motor skills, self-discipline and initiative. Teaching and learning outdoors is fun4 Often, the outdoors provides a change of pace from the classroom, which students and teachers enjoy. Studies have shown increased student enthusiasm for learning outdoors. Learning outdoors helps develop a sense of place and civic attitudes and behaviors5 Outdoor experiences help students increase their understanding of their natural and human communities which leads to a sense of place. -

Deconstructing Public Administration Empiricism

Deconstructing Public Administration Empiricism A paper written for Anti-Essentialism in Public Administration a conference in Fort Lauderdale, Florida March 2 and 3, 2007 Larry S. Luton Graduate Program in Public Administration Eastern Washington University 668 N. Riverpoint Blvd., Suite A Spokane, WA 99202-1660 509/358-2247 voice 509/358-2267 fax [email protected] Deconstructing Public Administration Empiricism: Short Stories about Empirical Attempts to Study Significant Concepts and Measure Reality Larry S. Luton Eastern Washington University Like much social science empiricism, public administration empiricism at its best recognizes that it presents probabilistic truth claims rather than universalistic ones. In doing so, public administration empiricists are (to a degree) recognizing the tenuousness of their claim that their approach to research is better connected to reality than research that does not adhere to empiricist protocols. To say that one is 95% confident that an empirical model explains 25% of the variation being studied is not a very bold claim about understanding reality. They are also masking a more fundamental claim that they know an objective reality exists. The existence of an objective reality is the essential foundation upon which empiricism relies for its claim to provide a research approach that is superior to all others and, therefore, is in a position to set the standards to which all research should be held (King, Keohane, & Verba 1994; Brady & Collier, 2004). In one of the most direct expressions of this claim, Meier has stated “There is an objective reality” (Meier 2005, p. 664). In support of that claim, he referenced 28,000 infant deaths in the U.S.