2Artboard 1 Copy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

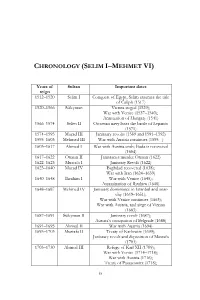

Selim I–Mehmet Vi)

CHRONOLOGY (SELIM I–MEHMET VI) Years of Sultan Important dates reign 1512–1520 Selim I Conquest of Egypt, Selim assumes the title of Caliph (1517) 1520–1566 Süleyman Vienna sieged (1529); War with Venice (1537–1540); Annexation of Hungary (1541) 1566–1574 Selim II Ottoman navy loses the battle of Lepanto (1571) 1574–1595 Murad III Janissary revolts (1589 and 1591–1592) 1595–1603 Mehmed III War with Austria continues (1595– ) 1603–1617 Ahmed I War with Austria ends; Buda is recovered (1604) 1617–1622 Osman II Janissaries murder Osman (1622) 1622–1623 Mustafa I Janissary Revolt (1622) 1623–1640 Murad IV Baghdad recovered (1638); War with Iran (1624–1639) 1640–1648 İbrahim I War with Venice (1645); Assassination of İbrahim (1648) 1648–1687 Mehmed IV Janissary dominance in Istanbul and anar- chy (1649–1651); War with Venice continues (1663); War with Austria, and siege of Vienna (1683) 1687–1691 Süleyman II Janissary revolt (1687); Austria’s occupation of Belgrade (1688) 1691–1695 Ahmed II War with Austria (1694) 1695–1703 Mustafa II Treaty of Karlowitz (1699); Janissary revolt and deposition of Mustafa (1703) 1703–1730 Ahmed III Refuge of Karl XII (1709); War with Venice (1714–1718); War with Austria (1716); Treaty of Passarowitz (1718); ix x REFORMING OTTOMAN GOVERNANCE Tulip Era (1718–1730) 1730–1754 Mahmud I War with Russia and Austria (1736–1759) 1754–1774 Mustafa III War with Russia (1768); Russian Fleet in the Aegean (1770); Inva- sion of the Crimea (1771) 1774–1789 Abdülhamid I Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774); War with Russia (1787) -

THE MATERIAL CULTURE in the ISTANBUL HOUSES THROUGH the EYES of BRITISH TRAVELER JULIA PARDOE (D.1862)

THE MATERIAL CULTURE IN THE ISTANBUL HOUSES THROUGH THE EYES OF BRITISH TRAVELER JULIA PARDOE (d.1862) by GÜLBAHAR RABİA ALTUNTAŞ Submitted to the Institute of Social Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Sabancı University March 2017 © Gülbahar Rabia Altuntaş 2017 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT THE MATERIAL CULTURE IN THE ISTANBUL HOUSES THROUGH THE EYES OF BRITISH TRAVELER JULIA PARDOE (d.1862) Gülbahar Rabia Altuntaş M.A. in History Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Tülay Artan Keywords: Ottoman material culture, 19th century travel writings, middle-class travelers, Ottoman houses, decoration, interior design This thesis focuses on the domestic interiors and material worlds of Istnabul houses through Julia Pardoe’s travel account “The City of the Sultan; and Domestic Manners of the Turks, in 1836”. She traveled to Ottoman lands in 1836 and wrote of her experiences and observations in her account. Firstly, the thesis will present that Julia Pardoe's account was one of the early examples of 19th-century travel writings. It will analyze how travel writing was transformed in the 19th century by middle class women travelers through their critical approach to previous travelers and through their constructing of a new perspective and discourses. Secondly, the life of householders she visited will be evaluated to understand the atmosphere in these houses. This also allows us to position them within social hierarchy as either royal, high-ranking or upper middle class. Lastly, these houses will be analyzed on the basis of Pardoe’s detailed descriptions, considering the main issues of material culture such as comfort, heating, luxury, decoration and design. -

THE ISLAMIC COINS Athens at BY

THE ATHENIANAGORA RESULTS OF EXCAVATIONS CONDUCTED BY THE AMERICAN SCHOOL OF CLASSICAL STUDIES AT ATHENS VOLUME IX THE ISLAMIC COINS Athens at BY GEORGE C. MILES Studies CC-BY-NC-ND. License: Classical of o go only. .,0,00 cc, 000, .4. *004i~~~a.L use School personal American © For THE AMERICAN SCHOOL OF CLASSICAL STUDIES AT ATHENS PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY 1962 American School of Classical Studies at Athens is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve, and extend access to The Athenian Agora ® www.jstor.org PUBLISHED WITH THE AID OF A GRANT FROM MR. JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER, JR. Athens at Studies CC-BY-NC-ND. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED License: Classical of only. use School personal American © For PRINTED IN GERMANY at J.J. AUGUSTIN GLO CKSTADT PREFACE T he present catalogue is in a sense the continuation of the catalogue of coins found in the Athenian Agora published by MissMargaret Thompson in 1954, TheAthenian Agora: Results of the Excavations conductedby the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Volume II, Athens Coins from the Roman throughthe Venetian Period. Miss Thompson's volume dealt with the at Roman, Byzantine, Frankish, Mediaeval European and Venetian coins. It was in the spring of 1954 that on Professor Homer A. Thompson's invitation I stopped briefly at the Agora on my way home from a year in Egypt and made a quick survey of the Islamic coins found in the ex- cavations. During the two weeks spent in Athens on that occasion I looked rapidly through the coins and that their somewhat and their relative Studies reported despite unalluring appearance CC-BY-NC-ND. -

An Ottoman Global Moment

AN OTTOMAN GLOBAL MOMENT: WAR OF SECOND COALITION IN THE LEVANT A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In History By Kahraman Sakul, M.A Washington, DC November, 18, 2009 Copyright 2009 by Kahraman Sakul All Rights Reserved ii AN OTTOMAN GLOBAL MOMENT: WAR OF SECOND COALITION IN THE LEVANT Kahraman Sakul, M.A. Dissertation Advisor: Gabor Agoston, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation aims to place the Ottoman Empire within its proper context in the Napoleonic Age and calls for a recognition of the crucial role of the Sublime Porte in the War of Second Coalition (1798-1802). The Ottoman-Russian joint naval expedition (1798-1800) to the Ionian Islands under the French occupation provides the framework for an examination of the Ottoman willingness to join the European system of alliance in the Napoleonic age which brought the victory against France in the Levant in the War of Second Coalition (1798-1802). Collections of the Ottoman Archives and Topkapı Palace Archives in Istanbul as well as various chronicles and treatises in Turkish supply most of the primary sources for this dissertation. Appendices, charts and maps are provided to make the findings on the expedition, finance and logistics more readable. The body of the dissertation is divided into nine chapters discussing in order the global setting and domestic situation prior to the forming of the second coalition, the Adriatic expedition, its financial and logistical aspects with the ensuing socio-economic problems in the Morea, the Sublime Porte’s relations with its protectorate – The Republic of Seven United Islands, and finally the post-war diplomacy. -

Diplomacy Might Be As Old As Politics Which Is As Old As State and People and As Long As the Debate of “We” and “Them” Existed, the Concept Is Likely to Prolong

UNDERSTANDING THE REFORM PROCESS OF THE OTTOMAN DIPLOMACY: A CASE OF MODERNIZATION? A THESIS SUBMITTED TO GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY CEM ERÜLKER IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE DEPARTMENT OF EUROPEAN STUDIES DECEMBER 2015 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Meliha Altunışık Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science Asst. Prof. Dr Galip Yalman Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science/ Asst. Prof. Dr Sevilay Kahraman Supervisor Examining Committee Members Yrd. Doç. Dr. Mustafa S. Palabıyık (TOBB ETU/IR) Doç. Dr. Sevilay Kahraman (METU/IR) Doç. Dr. Galip Yalman (METU/ADM) I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Cem Erülker Signature : iii ABSTRACT UNDERSTANDING THE REFORM PROCESS OF THE OTTOMAN DIPLOMACY : A CASE OF MODERNIZATION? Erülker, Cem MS., Department of European Studies Supervisor Assoc. Prof. Dr. Sevilay Kahraman December 2015, 97 pages The reasons that forced the Ottoman Empire to change its conventional method of diplomacy starting from late 18th century will be examined in this Thesis. -

Comparing Warrior Traditions: How the Janissaries and Samurai

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 55 Article 6 Number 55 Fall 2006 10-1-2006 Comparing Warrior Traditions: How the Janissaries and Samurai Maintained Their tS atus and Privileges During Centuries of Peace Oleg Benesch University of British Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Recommended Citation Benesch, Oleg (2006) "Comparing Warrior Traditions: How the Janissaries and Samurai Maintained Their tS atus and Privileges During Centuries of Peace," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 55 : No. 55 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol55/iss55/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Benesch: Comparing Warrior Traditions: How the Janissaries and Samurai Mai Oleg Benesch 37 COMPARING WARRIOR TRADITIONS: HOW THE JANISSARIES AND SAMURAI MAINTAINED THEIR STATUS AND PRIVILEGES DURING CENTURIES OF PEACE OLEG BENESCH UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA [email protected] History has witnessed the rise and fall of countless warrior classes, all of which were the tools of rulers, and many of which grew strong enough to usurp power and become rulers themselves. The existence of warrior classes in such a great variety of cultures and eras seems to indi- cate a universal human disposition for entrusting a certain group with the most dangerous and undesirable task of conducting warfare. In some cases, such as that of the samurai, the warriors came from within the society itself, and in others, including those of the Mamluks, Cossacks, and janissaries, members of certain ethnic or religious groups were compelled to serve as professional fighters. -

Rebellion, Janissaries and Religion in Sultanic Legitimisation in the Ottoman Empire

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Istanbul Bilgi University Library Open Access “THE FURIOUS DOGS OF HELL”: REBELLION, JANISSARIES AND RELIGION IN SULTANIC LEGITIMISATION IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE UMUT DENİZ KIRCA 107671006 İSTANBUL BİLGİ ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TARİH YÜKSEK LİSANS PROGRAMI PROF. DR. SURAIYA FAROQHI 2010 “The Furious Dogs of Hell”: Rebellion, Janissaries and Religion in Sultanic Legitimisation in the Ottoman Empire Umut Deniz Kırca 107671006 Prof. Dr. Suraiya Faroqhi Yard. Doç Dr. M. Erdem Kabadayı Yard. Doç Dr. Meltem Toksöz Tezin Onaylandığı Tarih : 20.09.2010 Toplam Sayfa Sayısı: 139 Anahtar Kelimeler (Türkçe) Anahtar Kelimeler (İngilizce) 1) İsyan 1) Rebellion 2) Meşruiyet 2) Legitimisation 3) Yeniçeriler 3) The Janissaries 4) Din 4) Religion 5) Güç Mücadelesi 5) Power Struggle Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü’nde Tarih Yüksek Lisans derecesi için Umut Deniz Kırca tarafından Mayıs 2010’da teslim edilen tezin özeti. Başlık: “Cehennemin Azgın Köpekleri”: Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’nda İsyan, Yeniçeriler, Din ve Meşruiyet Bu çalışma, on sekizinci yüzyıldan ocağın kaldırılmasına kadar uzanan sürede patlak veren yeniçeri isyanlarının teknik aşamalarını irdelemektedir. Ayrıca, isyancılarla saray arasındaki meşruiyet mücadelesi, çalışmamızın bir diğer konu başlığıdır. Başkentte patlak veren dört büyük isyan bir arada değerlendirilerek, Osmanlı isyanlarının karakteristik özelliklerine ve isyanlarda izlenilen meşruiyet pratiklerine ışık tutulması hedeflenmiştir. Çalışmamızda kullandığımız metot dâhilinde, 1703, 1730, 1807 ve 1826 isyanlarını konu alan yazma eserler karşılaştırılmış, müelliflerin, eserlerini oluşturdukları süreçteki niyetleri ve getirmiş oldukları yorumlara odaklanılmıştır. Argümanların devamlılığını gözlemlemek için, 1703 ve 1730 isyanları ile 1807 ve 1826 isyanları iki ayrı grupta incelenmiştir. 1703 ve 1730 isyanlarının ortak noktası, isyancıların kendi çıkarları doğrultusunda padişaha yakın olan ve rakiplerini bu sayede eleyen politik kişilikleri hedef almalarıdır. -

Mighty Guests of the Throne Note on Transliteration

Sultan Ahmed III’s calligraphy of the Basmala: “In the Name of God, the All-Merciful, the All-Compassionate” The Ottoman Sultans Mighty Guests of the Throne Note on Transliteration In this work, words in Ottoman Turkish, including the Turkish names of people and their written works, as well as place-names within the boundaries of present-day Turkey, have been transcribed according to official Turkish orthography. Accordingly, c is read as j, ç is ch, and ş is sh. The ğ is silent, but it lengthens the preceding vowel. I is pronounced like the “o” in “atom,” and ö is the same as the German letter in Köln or the French “eu” as in “peu.” Finally, ü is the same as the German letter in Düsseldorf or the French “u” in “lune.” The anglicized forms, however, are used for some well-known Turkish words, such as Turcoman, Seljuk, vizier, sheikh, and pasha as well as place-names, such as Anatolia, Gallipoli, and Rumelia. The Ottoman Sultans Mighty Guests of the Throne SALİH GÜLEN Translated by EMRAH ŞAHİN Copyright © 2010 by Blue Dome Press Originally published in Turkish as Tahtın Kudretli Misafirleri: Osmanlı Padişahları 13 12 11 10 1 2 3 4 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the Publisher. Published by Blue Dome Press 535 Fifth Avenue, 6th Fl New York, NY, 10017 www.bluedomepress.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available ISBN 978-1-935295-04-4 Front cover: An 1867 painting of the Ottoman sultans from Osman Gazi to Sultan Abdülaziz by Stanislaw Chlebowski Front flap: Rosewater flask, encrusted with precious stones Title page: Ottoman Coat of Arms Back flap: Sultan Mehmed IV’s edict on the land grants that were deeded to the mosque erected by the Mother Sultan in Bahçekapı, Istanbul (Bottom: 16th century Ottoman parade helmet, encrusted with gems). -

The Transformation of an Empire to a Nation-State: from the Ottoman Empire to the Republic of Turkey

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2014 The rT ansformation of an Empire to a Nation-State: From the Ottoman Empire to the Republic of Turkey Sarah R. Menzies Scripps College Recommended Citation Menzies, Sarah R., "The rT ansformation of an Empire to a Nation-State: From the Ottoman Empire to the Republic of Turkey" (2014). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 443. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/443 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Transformation of an Empire to a Nation-State: From the Ottoman Empire to the Republic of Turkey By Sarah R. Menzies SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS Professor Andrews Professor Ferguson 4/25/14 2 3 4 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 7 2. The Ottoman Empire 13 3. Population Policies 29 4. The Republic of Turkey 43 5. Conclusion 57 References 59 5 6 1. Introduction On the eve of the 99 th anniversary of the beginning of the mass deportations and massacres of the Armenian people, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdo ğan offered condolences for the mass killings that occurred in Anatolia against the Armenian population during World War I. (BBC News) He is the first Turkish prime minister to do so. However, he never uses the word genocide to describe the killings and continues to maintain that the deaths were part of wartime conflict. -

The Ottoman Empire, 1700–1922, Second Edition

This page intentionally left blank The Ottoman Empire, 1700–1922 The Ottoman Empire was one of the most important non-Western states to survive from medieval to modern times, and played a vital role in European and global history. It continues to affect the peoples of the Middle East, the Balkans, and Central and Western Europe to the present day. This new survey examines the major trends during the latter years of the empire; it pays attention to gender issues and to hotly de- bated topics such as the treatment of minorities. In this second edition, Donald Quataert has updated his lively and authoritative text, revised the bibliographies, and included brief bibliographies of major works on the Byzantine Empire and the post–Ottoman Middle East. This ac- cessible narrative is supported by maps, illustrations, and genealogical and chronological tables, which will be of help to students and non- specialists alike. It will appeal to anyone interested in the history of the Middle East. DONALD QUATAERT is Professor of History at Binghamton University, State University of New York. He has published many books on Middle East and Ottoman history, including An Economic and Social History of the Ottoman Empire, 1300–1914 (1994). NEW APPROACHES TO EUROPEAN HISTORY Series editors WILLIAM BEIK Emory University T . C . W . BLANNING Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge New Approaches to European History is an important textbook series, which provides concise but authoritative surveys of major themes and problems in European history since the Renaissance. Written at a level and length accessible to advanced school students and undergraduates, each book in the series addresses topics or themes that students of Eu- ropean history encounter daily: the series will embrace both some of the more “traditional” subjects of study, and those cultural and social issues to which increasing numbers of school and college courses are devoted. -

Ottoman Imperial Portraiture and Transcultural Aesthetics

1 OTTOMAN ImperiAL PORTRAITUre AND TrANSCULTURAL AESTHETICS In his book Other Colors, Orhan Pamuk invokes the early twentieth-century Turkish poet Yahya Kemal’s response to Gentile Bellini’s 1480 portrait, Sultan Mehmed II (fig. 4). It is a painting, Pamuk notes, that has achieved iconic status as a symbol of the Ottoman sultanate in modern Turkish culture. Pamuk writes, “what troubled him was that the hand that drew the portrait lacked a nationalist motive.”1 In Kemal’s work, Pamuk finds an approach to the Ottoman past that is riven with the doubts of a Turkish writer strug- gling to position that history as part of a national cultural identity in the early years of the Turkish Republic. Not least among the challenges for both authors grappling with the connection between Ottoman portraiture and contemporary cultural identity is the fact that the past, like the present, was ineluctably forged through an engagement with European aesthetics.2 Yet what also emerges from Pamuk’s short response to this paint- ing, and the constellation of other portraits by Ottoman and Persian artists that were inspired by it, is the prospect of an alternative, more enabling engagement with this history of transculturation. The uncertain authorship of some of these paintings and the alternative readings they provoke for Pamuk as he entertains their attribution on each side of the East-West divide, for example, function for him as a reminder that “cultural influences work in both directions with complexities difficult to fathom.”3 Pamuk’s eloquent, ambivalent response to the legacy of the Ottoman engagement with Venetian Renaissance art is a provocation to my own study of British artists’ por- traits of the Ottoman sultans in the nineteenth century. -

The Eighteenth Century: the Westernizers

chapter 9 The Eighteenth Century: the Westernizers Unlike the preceding years, the final decade of the eighteenth century is one of the most studied periods in Ottoman history.1 Selim III (1789–1807) succeeded Abdülhamid in the course of the war against Russia and was determined to enforce decisive reforms and restore Ottoman power. Even before his ascen- sion, from 1786 on, he had been corresponding with the French king Louis XVI with the help of his tutor, Ebubekir Ratıb Efendi, as seen in the previous chap- ter, with a view to seeking advice and diplomatic support for his plans.2 At the beginning of his reign, he called an enlarged council, consisting of more than 200 administrators and military and religious officials to ask their opinion on how to restore Ottoman power. It is interesting to note that this was not a novelty; such councils (meşveret) were regularly held at many administra- tive levels and they became increasingly important in the second half of the eighteenth century.3 For instance, we have the minutes of the council called after the disaster at Maçin (1791), arguably the central event that set Selim’s thoughts into action.4 After the end of the 1787–92 war, Selim III asked a series of high administration officials to write memoranda on the situation of the army and the state and to propose reforms or amendments, and then set out to make radical changes, particularly in the military. In the janissary corps, ad- ministrative roles were allocated to special supervisors, while the former aghas were left with military tasks alone.