Rehabilitation of the Camac River Under the Water Framework Directive: New Opportunities to Engage Local Communities and to Manage Flood Risk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 8 Hydrogeology & Hydrology

Chapter 8 Hydrogeology and Hydrology 8.0 Introduction Assessments have been undertaken of the likely significant environmental impacts on the hydrogeological and hydrological environments associated with the proposed National Paediatric Hospital Project. The project description is detailed in Chapter 2 of the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) and includes a number of development sites: within – or associated with – the main project site on the campus of St. James’s Hospital, Dublin 8: o a new children’s hospital and associated Family Accommodation Unit, sited in the west of the campus; o a new Children’s Research and Innovation Centre sited along James’s Street; o associated works to boundaries, roads, entrances, parking areas, hard and soft landscaping etc. within the application site boundary; and o a temporary construction compound, directly associated with the above developments at St. James’s Hospital Campus, at Davitt Road, Drimnagh, Dublin 12. 8-1 a new children's hospital satellite centre at Tallaght Hospital, Dublin 24; and a new children's hospital satellite centre at Connolly Hospital, Blanchardstown, Dublin 15. This Chapter provides a description of the existing hydrogeological and hydrological environments for each of the project sites, and a statement of the likely impacts associated with both the construction and operation phases of the National Paediatric Hospital Project. Mitigation measures are proposed in the form of ameliorative, remedial and reductive measures and residual impacts are described. Assessments for each site are detailed in this Chapter with relevant technical information included in Appendices: Appendix 8.1 Feasibility Study for a Potable Groundwater Supply, new children’s hospital, Arup Consulting Engineers. -

Inspector's Report ABP-306814-20

Inspector’s Report ABP-306814-20 Development Demolition of the existing single storey building (1,100 sq.m) last used as a motor business and its replacement with the construction of a 6 storey over basement hotel Location 30 Old Kilmainham, Kearns Place, Kilmainham, Dublin 8 Planning Authority Dublin City Council South Planning Authority Reg. Ref. 4623/19 Applicant(s) Ladas Property Company Unlimited Company (as part of Comer Group) Type of Application Permission Planning Authority Decision Refuse Type of Appeal First Party Appellant(s) Ladas Property Company Unlimited Company (as part of Comer Group) Observer(s) 1. Adrian Muldoon 2. E. Lawlor 3. P. Lawlor ABP-306814-20 Inspector’s Report Page 1 of 22 4. W & M Kinsella Date of Site Inspection 25th May 2020 Inspector Irené McCormack ABP-306814-20 Inspector’s Report Page 2 of 22 1.0 Site Location and Description The site is a corner site situated on the north side of Old Kilmainham Road. The site comprises a single storey industrial/warehouse building with a single storey reception/office to the front. There is surface car parking to the front and west of the site. The site was previously used as a garage and car sales but is now vacant. The area is characterised by a mixed form of urban development. The site is bound to the west by Kearns Place, which comprises two-storey terraced artisan type dwellings along its west side with a three storey Georgian type building on its western corner (with Old Kilmainham Road) opposite the site. Opposite the site on the south side of Old Kilmainham Road is an existing three-storey building office and warehouse. -

URBAN RIVER MANAGEMENT Séan Murray, Senior Engineer, South

National Hydrology Seminar 2000 Séan Murray URBAN RIVER MANAGEMENT Séan Murray, Senior Engineer, South Dublin County Council ABSTRACT The current population of South Dublin County Council is 240,000 and continues to grow. The rivers to which we discharge surface water have a limited capacity to accept further peak-flow discharge. Stormwater management and control of urban surface water run-off is essential. River flow management is illustrated by a case study of the River Camac, a tributary of the River Liffey, rising near Brittas Village and discharging at Heuston Station. Corkagh Park lies approximately midway along its reach. Upstream of the Park is mostly rural with high permeability while downstream is developed with low permeability and rapid run-offs. A flood event in June 1993 caused considerable damage to houses in the Clondalkin area downstream of Corkagh Park. SDCC subsequently devised the River Camac Improvement Scheme Phases 1 & 2 to minimise the future risk of flooding to the area. Phase 1 provided flood protection and flood alleviation for specific areas affected by the 1993 flood event. These works involved the construction of flood relief culverts and embankments, weir improvements, upgrading of surface water disposal systems and the removal of an old factory weir. The Phase 1 works were completed in 1995 at a cost of £215,000. Phase 2 provided a mechanism for the control of surface water volumes by means of attenuation ponds within Corkagh Park. The volume required was determined to be 55,000m3 from computer simulation models using ‘RBM-DOGGS’ output to provide input for a ‘Hydroworks’ analysis. -

KILMAINHAM-INCHICORE DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY Contents

KILMAINHAM-INCHICORE DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 4 2. THEMES 6 3. STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT 16 4. VISION 24 5. REGENERATION FRAMEWORK 28 6. URBAN REGENERATION & 40 DEVELOPMENT FUND 7. DELIVERY & PARTNERSHIPS 50 APPENDIX I - SPATIAL ANALYSIS APPENDIX II - MOVEMENT ANALYSIS APPENDIX III - LINKAGE ANALYSIS APPENDIX IV - NIAH SITES / PROTECTED STRUCTURES 1. INTRODUCTION KILMAINHAM-INCHICORE DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY Dublin City Council’s Kilmainham-Inchicore funding as Category “A” Projects under the Development Strategy is a non-statutory next round of the URDF later in 2021. high level study funded as a Category “B” This section sets out the basis for the Study under Call 1 of the (then) Department If Dublin City Council is successfully awarded of Housing, Planning and Local Government’s financing under the URDF it will be enabled Development Strategy, its purpose and (DHPLG) Urban Regeneration Development to undertake further detailed studies and Fund (URDF) to address opportunities for assessments of the projects before advancing what it attempts to achieve. urban regeneration and placemaking in to the planning consent process, detailed the Kilmainham-Inchicore area. The URDF design, and construction. application process is local authority led, prepared by the Executive. and determined The projects identified in the Development by the Minister for Housing and Local Strategy will be subject to a statutory Government (the Minister). The Development planning consent under the Planning and Strategy provides a framework for integrated, Development Act 2000 (as amended). All plan-led solutions, but does not authorise projects will be assessed concerning their specific projects. environmental impacts as part of a planning application. This includes compliance with The Development Strategy has been the Environmental Impact Assessment, Flood informed by the compilation of a Baseline Risk, and Habitats Directives. -

List of Rivers of Ireland

Sl. No River Name Length Comments 1 Abbert River 25.25 miles (40.64 km) 2 Aghinrawn Fermanagh 3 Agivey 20.5 miles (33.0 km) Londonderry 4 Aherlow River 27 miles (43 km) Tipperary 5 River Aille 18.5 miles (29.8 km) 6 Allaghaun River 13.75 miles (22.13 km) Limerick 7 River Allow 22.75 miles (36.61 km) Cork 8 Allow, 22.75 miles (36.61 km) County Cork (Blackwater) 9 Altalacky (Londonderry) 10 Annacloy (Down) 11 Annascaul (Kerry) 12 River Annalee 41.75 miles (67.19 km) 13 River Anner 23.5 miles (37.8 km) Tipperary 14 River Ara 18.25 miles (29.37 km) Tipperary 15 Argideen River 17.75 miles (28.57 km) Cork 16 Arigna River 14 miles (23 km) 17 Arney (Fermanagh) 18 Athboy River 22.5 miles (36.2 km) Meath 19 Aughavaud River, County Carlow 20 Aughrim River 5.75 miles (9.25 km) Wicklow 21 River Avoca (Ovoca) 9.5 miles (15.3 km) Wicklow 22 River Avonbeg 16.5 miles (26.6 km) Wicklow 23 River Avonmore 22.75 miles (36.61 km) Wicklow 24 Awbeg (Munster Blackwater) 31.75 miles (51.10 km) 25 Baelanabrack River 11 miles (18 km) 26 Baleally Stream, County Dublin 27 River Ballinamallard 16 miles (26 km) 28 Ballinascorney Stream, County Dublin 29 Ballinderry River 29 miles (47 km) 30 Ballinglen River, County Mayo 31 Ballintotty River, County Tipperary 32 Ballintra River 14 miles (23 km) 33 Ballisodare River 5.5 miles (8.9 km) 34 Ballyboughal River, County Dublin 35 Ballycassidy 36 Ballyfinboy River 20.75 miles (33.39 km) 37 Ballymaice Stream, County Dublin 38 Ballymeeny River, County Sligo 39 Ballynahatty 40 Ballynahinch River 18.5 miles (29.8 km) 41 Ballyogan Stream, County Dublin 42 Balsaggart Stream, County Dublin 43 Bandon 45 miles (72 km) 44 River Bann (Wexford) 26 miles (42 km) Longest river in Northern Ireland. -

Dublin City Biodiversity Action Plan 2015-2020 Dublin City Biodiversity Action Plan 2015-2020

Dublin City Biodiversity Action Plan 2015-2020 Dublin City Biodiversity Action Plan 2015-2020 1 Dublin City Biodiversity Action Plan 2015-2020 Table of Contents Introduction 03 Overview of Biodiversity in Dublin City 06 Theme 1: Strengthen the knowledge base of decision-makers for the conservation and management of biodiversity, and protect species and habitats of conservation value within Dublin City 12 1.1 Legally-Protected Species 15 1.2 Areas of Conservation Value 18 1.3 Public Parks 21 1.4 Invasive Species 22 1.5 Data Sharing and Publication 24 Theme 2: Strengthen the effectiveness of collaboration between all stakeholders for the conservation of biodiversity in the greater Dublin region 26 2.1 Dublin Bay Biosphere 29 2.2 Water Framework Directive 30 2.3 Dublin Mountains Partnership 31 Theme 3: Enhance opportunities for biodiversity conservation through green infrastructure, and promote ecosystem services in appropriate locations throughout the City 32 3.1 Dublin City’s Green Infrastructure Network 35 Theme 4: Develop greater awareness and understanding of biodiversity, and identify opportunities for engagement with communities and interest groups 38 4.1 Recognising Dublin City as a place full of biodiversity 41 4.2 Biodiversity Awareness Programme 42 4.3 Education and Awareness Resources 43 4.4 Facilitating Public Engagement and Volunteering 43 Implementation Strategy 44 Appendix 1: Stakeholders consulted during the preparation of 47 the Dublin City Biodiversity Action Plan 2015-2020 Appendix 2: Known or Previously Recorded Locations of Legally- 48 Protected Species within Dublin City Appendix 3: Common and Scientific Names of Flora Species 49 referred to in the Dublin City Biodiversity Action Plan 2015-2020 Appendix 4: Policy History and Legislative Context of the Dublin 51 City Biodiversity Action Plan 01 Dublin City Biodiversity Action Plan 2015-2020 View across coastal wetland habitats at North Bull Island. -

River Poddle FAS

RIVER PODDLE FLOOD ALLEVIATION SCHEME RESPONSE TO REQUEST FOR FURTHER INFORMATION October 2020 [Page Intentionally Left Blank] River Poddle Flood Alleviation Scheme Further Information Response SOUTH DUBLIN COUNTY COUNCIL & DUBLIN CITY COUNCIL IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE OFFICE OF PUBLIC WORKS RIVER PODDLE FLOOD ALLEVIATION SCHEME FURTHER INFORMATION RESPONSE Nicholas O’Dwyer Ltd Consulting Engineers Nutgrove Office Park Nutgrove Avenue Dublin 14 October 2020 PROJECT NO. 20662 Revision Reason for Revision Prepared by Reviewed by Approved by Issue Date First Issue for Review LMG, BD, JH, RC BD,LMG & CAS JO - 09/10/2020 Final Final for RFI Submission to ABP LMG, BD, JH, RC BD, LMG & CAS JO 19/10/2020 Nicholas O’Dwyer Ltd. October 2020 [Page Intentionally Left Blank] River Poddle Flood Alleviation Scheme Further Information Response CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 RFI NO. 1 - RESPONSE TO OBSERVATIONS 5 3 RFI NO. 2 - NATURAL FLOOD MANAGEMENT 7 4 RFI NO. 3 - CONFIRMATION OF WORKS AREAS & CONSTRUCTION COMPOUNDS 11 5 RFI NO. 4 - OUTLINE SURFACE WATER MANAGEMENT PLAN 13 6 RFI NO. 5 - PROPOSALS FOR WHITEHALL PARK 15 7 RFI NO. 6 – OPTIONS ASSESSMENT FOR ST. MARTIN’S DRIVE 21 8 RFI NO. 7 - ASSESSMENT OF IMPACTS 31 9 RFI NO. 8 - NET BIODIVERSITY GAIN 59 10 RFI NO. 9 - ECOLOGICAL ENHANCEMENT MEASURES 63 11 RFI NO. 10 - INFORMATION ON WATER QUALITY & REVIEW OF HYDRAULIC REPORT 77 12 RFI NO. 11 - DURATION OF CONSTRUCTION 83 13 RFI NO. 12 - INFORMATION ON CONSTRUCTION NOISE 85 14 RFI NO. 13 - DIFFICULTIES ENCOUNTERED IN PREPARATION OF EIAR 87 15 RFI NO. 14 - TOPIC OF “LAND” IN EIAR 89 16 RFI NO. -

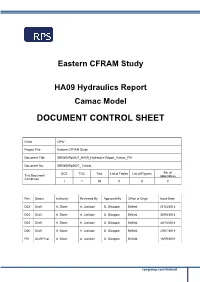

Camac Model DOCUMENT CONTROL SHEET

Eastern CFRAM Study HA09 Hydraulics Report Camac Model DOCUMENT CONTROL SHEET Client OPW Project Title Eastern CFRAM Study Document Title IBE0600Rp0027_HA09_Hydraulics Report_Camac_F01 Document No. IBE0600Rp0027_ Camac DCS TOC Text List of Tables List of Figures No. of This Document Appendices Comprises 1 1 55 0 0 3 Rev. Status Author(s) Reviewed By Approved By Office of Origin Issue Date D03 Draft A. Sloan A. Jackson G. Glasgow Belfast 21/03/2014 D04 Draft A. Sloan A. Jackson G. Glasgow Belfast 30/09/2014 D05 Draft A. Sloan A. Jackson G. Glasgow Belfast 30/10/2014 D06 Draft A. Sloan A. Jackson G. Glasgow Belfast 29/01/2015 F01 Draft Final A. Sloan A. Jackson G. Glasgow Belfast 16/09/2016 rpsgroup.com/ireland Copyright Copyright - Office of Public Works. All rights reserved. No part of this report may be copied or reproduced by any means without prior written permission from the Office of Public Works. Legal Disclaimer This report is subject to the limitations and warranties contained in the contract between the commissioning party (Office of Public Works) and RPS Group Ireland rpsgroup.com/ireland Eastern CFRAM Study HA09 Hydraulics Report – DRAFT FINAL TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 HYDRAULIC MODEL DETAILS ................................................................................................ 4 4.5 CAMAC MODEL ................................................................................................................ 4 4.5.1 General Hydraulic Model Information ............................................................... 4 4.5.2 -

Corkagh Park Screen Med Res.Pdf

South (Dublin County Council Elected MemSers Clondalkin Tallaght South Curran, John, Leas Cathaoirleach (FF), 15 Knockmeenagh Rd., Clondalkin, D. 22 Billane, Mick, (LAB), 6 Ellensborough Dale, Kiltipper, Tallaght, D. 24 Dowds, Robert, (LAB), 43 Castle Park, Clondalkin, D. 22 McGrath, Colm, (IND), 'Tower House', 48 Tower Rd., Clondalkin, D. 22 Crowe, Sean, (SF), 16 Raheen Green, Tallaght, D. 24 Ridge, Therese, (FG), 4 St. Patrick's Avenue, Clondalkin, D. 22 Daly, Jim, (FF), 59 Coolamber Drive, Rathcoole, Co. Dublin Tyndall, Colm, (PD), 15 St. Brigid's Drive, Clondalkin, D. 22 Hannon, John, (FF), 11 Knocklyon Heights, Firhouse Rd., D. 16 Rabbitte, Pat, (LAB), 56, Monastery Drive, D. 22 Lucan Doherty-Ryan, Deirdre, (FF), 32 Kennelsfort Rd., Palmerstown, D. 20 Gogarty, Paul, (GR), 34 Cherbury Park Rd., Lucan, Co. Dublin Keating, Derek, (IND), P.C. 66 Beech Park, Lucan, Co. Dublin Terenure/Rathfamham Tuffy, Joanna, (LAB), 111 Esker Lawns, Lucan Co. Dublin Ardagh, Maire, (FF), 168 Walkinstown Road, D. 12 Keane Cait, Cathaoirleach (PD), 26 Rushbrook Court, Templeogue, Dublin 6W Tallaght Central Lahart, John, (FF), 6 Orlagh Grange, Scholarstown Rd., Rathfarnham, D. 16 Daly, Mark, (SF), 31 Cill Cais, Old Bawn, Tallaght, D. 24 Laing, Stanley, (FG), 86 Templeville Road, Terenure, Dublin 6W Hayes, Brian, (FG), 48 Dunmore Park, Kingswood Heights, D. 24 Ormonde, Ann, (FF), C/0 Seanad Eireann, D. 2 Maloney, Eamonn, (LAB), 84 St. Maelruans Park, Tallaght, D. 24. Walsh, Eamonn, (LAB), 133 Limekiln Green, Walkinstown, D. 12 0 Connor, Charlie, (FF), C/0 South Dublin County Council, Tallaght, D. 24 Tipping, Don, (LAB), "Belpark" Elmcastle Drive, Kilnamanagh, D. -

Eastern CFRAM Study HA09 Inception Report

Eastern CFRAM Study HA09 Inception Report IBE0600Rp0008_F02/Aug2012 rpsgroup.com/ireland Eastern CFRAM Study HA09 Inception Report DOCUMENT CONTROL SHEET Client OPW Project Title Eastern CFRAM Study Document Title IBE0600Rp0008_HA09 Inception Report_F02 Document No. IBE0600Rp0008 DCS TOC Text List of Tables List of Figures No. of This Document Appendices Comprises 1 1 144 1 1 5 Rev. Status Author(s) Reviewed By Approved By Office of Origin Issue Date D01 Preliminary Various M Brian G Glasgow Belfast Internal Feb 2012 D02 Draft Various M Brian G Glasgow Belfast Mar 2012 F01 Draft Final Various M Brian G Glasgow Belfast July 2012 F02 Final Various M Brian G Glasgow Belfast Aug 2012 rpsgroup.com/ireland Copyright: Copyright - Office of Public Works. All rights reserved. No part of this report may be copied or reproduced by any means without prior written permission of the Office of Public Works. Legal Disclaimer: This report is subject to the limitations and warranties contained in the contract between the commissioning party (Office of Public Works) and RPS Group Ireland. Eastern CFRAM Study HA09 Inception Report – FINAL TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 OBJECTIVE OF THIS INCEPTION REPORT ............................................................................. 3 1.1.1 Hydrometric Area 09 ........................................................................................ 3 1.1.2 Dodder CFRAM Study and Tolka -

Corkagh Park Pavilion

FLOOD RISK ASSESSMENT, CORKAGH PARK PAVILION _____________________________________ Technical Report Prepared For CAAS 24-26 Ormond Quay Upper, Dublin 7 D07 DAV9 _____________________________________ Technical Report Prepared By Paul Conaghan Environmental Consultant Teri Hayes Director (Water) _____________________________________ Our Reference PC/20/11412WR01 ____________________________________ Date of Issue 12 February 2020 _____________________________________ PC/20/11412WR01 AWN Consulting Limited Document History Document Reference Original Issue Date PC/19/111412WR01 12 February 2020 Revision Level Revision Date Description Sections Affected 1 4 Record of Approval Details Written by Approved by Signature Name Paul Conaghan Teri Hayes Title Environmental Consultant Director (Water) Date 12 February 2020 12 February 2020 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Page 2 PC/20/11412WR01 AWN Consulting Limited EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AWN Consulting Ltd (AWN) has been appointed by CAAS Ltd to undertake a Flood Risk Assessment (“FRA”) within and surrounding a proposed sports pavilion development at Corkagh Park. The site is currently a mixture of hardstanding (car park and roads with associated surface water drainage) and greenfield located in the western section of the wider Corkagh Park/ Demesne. The existing car park within the proposed development boundary which will be retained. A number of playing pitches are located to the north with the R136 situated to the west. The site is currently zoned as objective OS - To preserve and provide for open space and recreational amenities as per the SDCC Development Plan. The OPW online flood map tools were consulted and indicated there has been no previously recorded flood event at the proposed development site. Flood events have been recorded both upstream and downstream of the proposed development. -

Irish Rivers 2040 Report-180927-IQ

Irish rivers 2040Designing Irelands ‘next generation’ flood defences Flumina Hiberniae 2040 Flumina Hiberniae 2040 Irish Rivers 2040 CONTENTS Irish Supervisory team Flumina Dutch Team Flumina Hiberniae Co funded by Hiberniae REDscape Landscape & Urbanism (lead) The Creative Industries Fund NL. Office of Public Works Dingeman Deijs Architects http://stimuleringsfonds.nl/en 1. Introduction Cork City Council Palmbout Urban Landscape Dublin City Council Van Paridon de Groot Landscape architects 8 - A design led approach Fingal County Council 2. Background 10 - The cost of flooding 10 - Flood protection as a National Investment opportunity 10 - Comparing the Irish and Dutch Approaches to Flood Protection 10 - Anticipating Changing European Policy 3. How the project worked 12. The living lab project Flumina Hiberniae 2040 12. Workshops, breakout sessions and presentations 4. The current flood protection approach 14 - The Current Process for selecting and delivering flood protection 14 - Evaluation of the Current Process for selecting and delivering flood Protection Irish supervisory Committee representatives Mark Adamson (chief engineer, OPW) Eamon Walsh (engineer, Cork City Council) 5. What is a design led approach? Gerry Glabby ( ecologist, Fingal County Council) 16 - Design thinking versus scientific thinking Gerard O Connell( enginer, Dublin City Council) 16 - A design led approach to flood defences - the Dutch Method of water management 16 - Translating the organisational issue in terms of theory 19 - Why it is worth investigating? 20 - Benefits to the organisation. 6. Project Case Studies Dutch Design Team representatives 22 - Cork and Dublin regions- developing a toolbox of options Patrick Mc Cabe ( landscape architect, REDscape Landscape & Urbanism) Overview of Case studies Dingeman Deijs (architect, Dingeman Deijs architects, 24- Case study 1.