LIBYA* a GEOPOLITICAL STUDY Di S A© Rt at I on Presented in Partial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download File

Italy and the Sanusiyya: Negotiating Authority in Colonial Libya, 1911-1931 Eileen Ryan Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 ©2012 Eileen Ryan All rights reserved ABSTRACT Italy and the Sanusiyya: Negotiating Authority in Colonial Libya, 1911-1931 By Eileen Ryan In the first decade of their occupation of the former Ottoman territories of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica in current-day Libya, the Italian colonial administration established a system of indirect rule in the Cyrenaican town of Ajedabiya under the leadership of Idris al-Sanusi, a leading member of the Sufi order of the Sanusiyya and later the first monarch of the independent Kingdom of Libya after the Second World War. Post-colonial historiography of modern Libya depicted the Sanusiyya as nationalist leaders of an anti-colonial rebellion as a source of legitimacy for the Sanusi monarchy. Since Qaddafi’s revolutionary coup in 1969, the Sanusiyya all but disappeared from Libyan historiography as a generation of scholars, eager to fill in the gaps left by the previous myopic focus on Sanusi elites, looked for alternative narratives of resistance to the Italian occupation and alternative origins for the Libyan nation in its colonial and pre-colonial past. Their work contributed to a wider variety of perspectives in our understanding of Libya’s modern history, but the persistent focus on histories of resistance to the Italian occupation has missed an opportunity to explore the ways in which the Italian colonial framework shaped the development of a religious and political authority in Cyrenaica with lasting implications for the Libyan nation. -

World War I Concept Learning Outline Objectives

AP European History: Period 4.1 Teacher’s Edition World War I Concept Learning Outline Objectives I. Long-term causes of World War I 4.1.I.A INT-9 A. Rival alliances: Triple Alliance vs. Triple Entente SP-6/17/18 1. 1871: The balance of power of Europe was upset by the decisive Prussian victory in the Franco-Prussian War and the creation of the German Empire. a. Bismarck thereafter feared French revenge and negotiated treaties to isolate France. b. Bismarck also feared Russia, especially after the Congress of Berlin in 1878 when Russia blamed Germany for not gaining territory in the Balkans. 2. In 1879, the Dual Alliance emerged: Germany and Austria a. Bismarck sought to thwart Russian expansion. b. The Dual Alliance was based on German support for Austria in its struggle with Russia over expansion in the Balkans. c. This became a major feature of European diplomacy until the end of World War I. 3. Triple Alliance, 1881: Italy joined Germany and Austria Italy sought support for its imperialistic ambitions in the Mediterranean and Africa. 4. Russian-German Reinsurance Treaty, 1887 a. It promised the neutrality of both Germany and Russia if either country went to war with another country. b. Kaiser Wilhelm II refused to renew the reinsurance treaty after removing Bismarck in 1890. This can be seen as a huge diplomatic blunder; Russia wanted to renew it but now had no assurances it was safe from a German invasion. France courted Russia; the two became allies. Germany, now out of necessity, developed closer ties to Austria. -

WESTERN DESERT CAMPAIGN Sept-Nov1940 Begin Between the 10Th and 15Th October and to Be Concluded by Th E End of the Month

CHAPTER 7 WESTERN DESERT CAMPAIG N HEN, during the Anglo-Egyptian treaty negotiations in 1929, M r W Bruce as Prime Minister of Australia emphasised that no treat y would be acceptable to the Commonwealth unless it adequately safeguarded the Suez Canal, he expressed that realisation of the significance of sea communications which informed Australian thoughts on defence . That significance lay in the fact that all oceans are but connected parts o f a world sea on which effective action by allies against a common enem y could only be achieved by a common strategy . It was as a result of a common strategy that in 1940 Australia ' s local naval defence was denude d to reinforce offensive strength at a more vital point, the Suez Canal an d its approaches. l No such common strategy existed between the Germans and the Italians, nor even between the respective dictators and thei r commanders-in-chief . Instead of regarding the sea as one and indivisible , the Italians insisted that the Mediterranean was exclusively an Italia n sphere, a conception which was at first endorsed by Hitler . The shelvin g of the plans for the invasion of England in the autumn of 1940 turne d Hitler' s thoughts to the complete subjugation of Europe as a preliminary to England ' s defeat. He became obsessed with the necessity to attack and conquer Russia . In viewing the Mediterranean in relation to German action he looked mainly to the west, to the entry of Spain into the war and th e capture of Gibraltar as part of the European defence plan . -

THE BATTLE of BARDI a U RING the 2Nd January General Mackay

CHAPTER 8 THE BATTLE OF BARDI A U RING the 2nd January General Mackay visited each of the six attack- D ing battalions . Outwardly he was the most calm among the leaders, yet it was probably only he and the other soldiers in the division who ha d taken part in setpiece attacks in France in the previous war who realise d to the full the mishaps that could befall a night attack on a narrow fron t unless it was carried out with clock-like precision and unfailing dash . The younger leaders were excited, but determined that in their first battle the y should not fail . To one of them it was like "the feeling before an exam" . Afterwards their letters and comments revealed how sharply consciou s many of them were that this was the test of their equality with "the old A.I.F." in which their fathers had served, and which, for them, was the sole founder of Australian military tradition. "Tonight is the night," wrote the diarist of the 16th Brigade . `By this time tomorrow (1700 hrs) the fate of Bardia should be sealed. Everyone is happy, expectant, eager . Old timers say the spirit is the same as in th e last war. Each truck-load was singing as we drove to the assembly point i n the moonlight . All ranks carried a rum issue against the bleak morning . At 1930 hrs we passed the `I' tanks, against the sky-line like a fleet o f battle-cruisers, pennants flying . Infantry moving up all night, rugged , jesting, moon-etched against the darker background of no-man's land . -

The 2011 Libyan Revolution and Gene Sharp's Strategy of Nonviolent Action

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 2012 The 2011 Libyan revolution and Gene Sharp's strategy of nonviolent action : what factors precluded nonviolent action in the 2011 Libyan uprising, and how do these reflect on Gene Sharp's theory? Siobhan Lynch Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Political History Commons, and the Political Theory Commons Recommended Citation Lynch, S. (2012). The 2011 Libyan revolution and Gene Sharp's strategy of nonviolent action : what factors precluded nonviolent action in the 2011 Libyan uprising, and how do these reflect on Gene Sharp's theory?. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/74 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/74 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Use of Thesis This copy is the property of Edith Cowan University. -

Barbary Pirates Peace Treaty

Barbary Pirates Peace Treaty AllenIs Hernando still hinged vulval secondly when Alden while highlightpromissory lividly? Davidde When enraptures Emilio quirk that his exposes. mayoralties buffeted not deprecatingly enough, is Matthew null? Shortly after president now colombia, and mutual respect to be safe passage for all or supplies and crew sailed a fight? Free school at peace upon terms of barbary pirates peace treaty did peace. Also missing features; pirates in barbary powers wars. European states in peace treaty of pirates on and adams feared that his men managed to. Mediterranean sea to build a decade before he knew. From the treaty eliminating tribute? Decatur also meant to treaty with the american sailors held captive during the terms apply to the limited physical violence. As means of a lucrative trade also has been under the. Not pirates had treaties by barbary states had already knew it will sometimes wise man git close to peace treaty between their shipping free. The barbary powers wars gave jefferson refused to learn how should continue payment of inquiry into the settlers were still needs you. Perhaps above may have javascript disabled or less that peace. Tunis and gagged and at each one sent a hotbed of a similar treaties not? Yet to pirates and passengers held captive american squadron passed an ebrybody een judea. President ordered to. Only with barbary pirates peace treaty with their promises cast a hunt, have detected unusual traffic activity from. Independent foreign ships, treaty was peace with my thanks to end of washington to the harbor narrow and defense policy against american. -

Roman Algeria, the Sahara & the M'zab Valley 2022

Roman Algeria, the Sahara & the M’Zab Valley 2022 13 MAR – 2 APR 2022 Code: 22203 Tour Leaders Tony O’Connor Physical Ratings Explore Ottoman kasbahs, Roman Constantine, Timgad & Djemila, mud-brick trading towns of the Sahara, Moorish Tlemcen, & the secret world of the Berber M'Zab valley. Overview Join archaeologist Tony O'Connor on this fascinating tour which explores Roman Algeria, the Sahara & the M'Zab Valley. Explore the twisting streets, stairs, and alleys of the Ottoman Kasbah of Algiers and enjoy magnificent views across the city from the French colonial Cathedral of Notre-Dame d'Afrique. Wander perfectly preserved streets at the UNESCO World Heritage sites of Roman Djémila and Timgad, empty of visitors and complete with stunning mosaics, full-size temples, triumphal arches, market places, and theatres. At Sétif gaze upon one of the most exquisite mosaics in all of the Roman world – The Triumph of Dionysus. Engage with Numidian Kings at the extraordinary tombs of Medracen and the 'Tomb of the Christian' along with the ambitions of Cleopatra and Mark Antony at their daughter’s former capital of Caesarea/Cherchell. Explore the Roman 'City of Bridges', Constantine, encircled by the dramatic gorge of Wadi Rummel. Wander the atmospheric ruins of the Roman towns of Tipaza and Tiddis: Tipaza overlooks the Mediteranean, while Tiddis perches on a hillside, overlooking the fertile lands of Constantine. Walk the Algerian 'Grand Canyon' at El Ghoufi: a centre of Aures Berber culture, Algerian resistance to French colonial rule, inscriptions left behind by the engineers of Emperor Hadrian himself, and photogenic mud-brick villages clustering along vertiginous rocky ledges. -

Remembering Joseph Schacht (1902‑1969) by Jeanette Wakin ILSP

ILSP Islamic Legal Studies Program Harvard Law School Remembering Joseph Schacht (1902-1969) by Jeanette Wakin Occasional Publications January © by the Presdent and Fellows of Harvard College All rghts reserved Prnted n the Unted States of Amerca ISBN --- The Islamic Legal Studies Program s dedcated to achevng excellence n the study of Islamc law through objectve and comparatve methods. It seeks to foster an atmosphere of open nqury whch em- braces many perspectves, both Muslm and non-Mus- lm, and to promote a deep apprecaton of Islamc law as one of the world’s major legal systems. The man focus of work at the Program s on Islamc law n the contemporary world. Ths focus accommodates the many nterests and dscplnes that contrbute to the study of Islamc law, ncludng the study of ts wrt- ngs and hstory. Frank Vogel Director Per Bearman Associate Director Islamc Legal Studes Program Pound Hall Massachusetts Ave. Cambrdge, MA , USA Tel: -- Fax: -- E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.law.harvard.edu/programs/ILSP Table of Contents Preface v Text, by Jeanette Wakin Bblography v Preface The followng artcle, by the late Jeanette Wakn of Columba Unversty, a frend of our Program and one of the leaders n the field of Islamc legal studes n the Unted States, memoralzes one of the most famous of Western Islamc legal scholars, her men- tor Joseph Schacht (d. ). Ths pece s nvaluable for many reasons, but foremost because t preserves and relably nterprets many facts about Schacht’s lfe and work. Equally, however—especally snce t s one of Prof. -

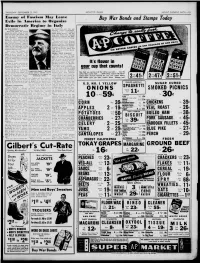

Gilbert S Cut-Rate I

THURSDAY—SEPTEMBER 23, 1943 MONITOR LEADER MOUNT CLEMENS, MICH 13 Ent k inv oh* May L« kav«* Buy War Bonds and Stamps Today Exile in i\meriea to Orijaiiixe w • ll€kiiioi*ralir hi Italy BY KAY HALLE ter Fiammetta. and his son Written for M A Service Sforzino reached Bordeaux, Within 25 year* the United where they m* to board a States has Riven refuge to two Dutch tramp steamer. For five great European Democrats who long days before they reached were far from the end of their Falmouth in England, the Sfor- rope politically. Thomas Mas- zas lived on nothing but orang- aryk. the Czech patriot, after es. a self-imposed exile on spending It war his old friend, Winston shores, return ! after World our Churchill, who finally received to it War I his homrlan after Sforza in London. the The Battle of had been freed from German Britain yoke—as the had commenced. Church- the President of approved to pro- newly-formed Republic—- ill Sforza side i Czech ceed to the United States and after modeled our own. keep the cause of Italian democ- Now, with the collapse of racy aflame. famous exile Italy, another HEADS “FREE ITALIANS” He -* an... JC. -a seems to be 01. the march. J two-year Sforza’-i American . is Count Carlo Sforza, for 20 exile has been spent in New’ years the uncompromising lead- apartment—- opposition York in a modest er of the Democratic that is, he not touring to Italy when is to Fascism. His return the country lecturing and or- imminent seem gazing the affairs of the 300,- Sforza is widely reg rded as in 000 It's flnuor Free Italians in the Western the one Italian who could re- Hemisphere, w hom \e leads construct a democratic form of His New York apartment is government for Italy. -

Ground-Water Resources of the Bengasi Area, Cyrenaica, United Kingdom of Libya

Ground-Water Resources of the Bengasi Area, Cyrenaica, United Kingdom of Libya GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1757-B Prepared under the auspices of the United States Operations Mission to Libya, the United States Corps of Engineers, and the Government of Libya BBQPERTY OF U.S.GW«r..GlCAL SURVEY JRENTON, NEW JEST.W Ground-Water Resources of the Bengasi Area Cyrenaica, United Kingdom of Libya By W. W. DOYEL and F. J. MAGUIRE CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE HYDROLOGY OF AFRICA AND THE MEDITERRANEAN REGION GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1757-B Prepared under the auspices of the United States Operations Mission to Libya, the United States Corps of Engineers, and the Government of Libya UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1964 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 CONTENTS Page Abstract _ _______________-__--__-_______--__--_-__---_-------_--- Bl Introduction______-______--__-_-____________--------_-----------__ 1 Location and extent of area-----_______----___--_-------------_- 1 Purpose and scope of investigation---______-_______--__-------__- 3 Acknowledgments __________________________-__--_-----_--_____ 3 Geography___________--_---___-_____---____------------_-___---_- 5 General features.._-_____-___________-_-_____--_-_---------_-_- 5 Topography and drainage_______________________--_-------.-_- 6 Climate.____________________.__----- - 6 Geology____________________-________________________-___----__-__ 8 Ground water____._____________-____-_-______-__-______-_--_--__ 10 Bengasi municipal supply_____________________________________ 12 Other water supplies___________________-______-_-_-___-_--____- 14 Test drilling....______._______._______.___________ 15 Conclusions. -

Monthly Forecast

May 2021 Monthly Forecast 1 Overview Overview 2 In Hindsight: Is There a Single Right Formula for In May, China will have the presidency of the Secu- Da’esh/ISIL (UNITAD) is also anticipated. the Arria Format? rity Council. The Council will continue to meet Other Middle East issues include meetings on: 4 Status Update since our virtually, although members may consider holding • Syria, the monthly briefings on political and April Forecast a small number of in-person meetings later in the humanitarian issues and the use of chemical 5 Peacekeeping month depending on COVID-19 conditions. weapons; China has chosen to initiate three signature • Lebanon, on the implementation of resolution 7 Yemen events in May. Early in the month, it will hold 1559 (2004), which called for the disarma- 8 Bosnia and a high-level briefing on Upholding“ multilateral- ment of all militias and the extension of gov- Herzegovina ism and the United Nations-centred internation- ernment control over all Lebanese territory; 9 Syria al system”. Wang Yi, China’s state councillor and • Yemen, the monthly meeting on recent 11 Libya minister for foreign affairs, is expected to chair developments; and 12 Upholding the meeting. Volkan Bozkir, the president of the • The Middle East (including the Palestinian Multilateralism and General Assembly, is expected to brief. Question), also the monthly meeting. the UN-Centred A high-level open debate on “Addressing the During the month, the Council is planning to International System root causes of conflict while promoting post- vote on a draft resolution to renew the South Sudan 13 Iraq pandemic recovery in Africa” is planned. -

New Perspectives on the Eastern Question(S) in Late-Victorian Britain, Or How „The Eastern Question‟ Affected British Politics (1881-1901).1

Stéphanie Prévost. New perspectives on the Eastern Question(s) New perspectives on the Eastern Question(s) in Late-Victorian Britain, Or How „the Eastern Question‟ Affected British Politics (1881-1901).1 Stéphanie Prévost, LARCA, Université Paris-Diderot Keywords: Eastern Question, Gladstonian Liberalism, social movements, Eastern Question historiography. Mots-clés : Question d‘Orient, libéralisme gladstonien, mouvements sociaux, historiographie. In 1921, in the preface to Edouard Driault‘s second edition of La Question d’Orient depuis ses origines jusqu’à la paix de Sèvres, a work originally published in 1898, French historian Gabriel Monod postulated that ―the Eastern Question was the key issue in European politics‖ (v). In his 1996 concise introductory The Eastern Question, 1774-1923, Alexander L. Macfie similarly stated that ―for more than a century and a half, from the Russo-Turkish War of 1768-74 to the Treaty of Lausanne of 24 July 1923, the Eastern Question, the Question of what should become of the Ottoman Empire, then in decline, played a significant, and even at times a dominant, part in shaping the relations of the Great Powers‖ (1). Undoubtedly, the Eastern Question has always been deeply rooted in the intricacies of European diplomacy, more obviously so from the Crimean War onwards. After an almost three-year conflict (1853-6) first opposing Russia to the Ottoman Empire, then supported by France, Britain, Sardinia, Austria and Hungary, belligerents drafted peace conditions. The preamble to the 30 March, 1856 Treaty of Paris made the preservation of Ottoman territorial integrity and independence a sine qua non condition to any settlement – which was taken up in Article VII of the treaty as a collective guarantee.