The Haggadah of the Kaifeng Jews of China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

Some Highlights of the Mossad Harav Kook Sale of 2017

Some Highlights of the Mossad HaRav Kook Sale of 2017 Some Highlights of the Mossad HaRav Kook Sale of 2017 By Eliezer Brodt For over thirty years, starting on Isru Chag of Pesach, Mossad HaRav Kook publishing house has made a big sale on all of their publications, dropping prices considerably (some books are marked as low as 65% off). Each year they print around twenty new titles. They also reprint some of their older, out of print titles. Some years important works are printed; others not as much. This year they have printed some valuable works, as they did last year. See here and here for a review of previous year’s titles. If you’re interested in a PDF of their complete catalog, email me at [email protected] As in previous years, I am offering a service, for a small fee, to help one purchase seforim from this sale. The sale’s last day is Tuesday. For more information about this, email me at Eliezerbrodt-at-gmail.com. Part of the proceeds will be going to support the efforts of the Seforim Blog. What follows is a list and brief description of some of their newest titles. 1. הלכות פסוקות השלם,ב’ כרכים, על פי כת”י ששון עם מקבילות מקורות הערות ושינויי נוסחאות, מהדיר: יהונתן עץ חיים. This is a critical edition of this Geonic work. A few years back, the editor, Yonason Etz Chaim put out a volume of the Geniza fragments of this work (also printed by Mossad HaRav Kook). 2. ביאור הגר”א ,לנ”ך שיר השירים, ב, ע”י רבי דוד כהן ור’ משה רביץ This is the long-awaited volume two of the Gr”a on Shir Hashirim, heavily annotated by R’ Dovid Cohen. -

The KA Kosher Certification

Kosher CertifiCation the Kashrut authority of australia & new Zealand the Ka Kosher CertifiCation he Kashrut Authority (KA) offers a wide range of exceptional T Kosher Certification services to companies in Australia, New Zealand and Asia. A trusted global leader in the field of Kosher Certification for more than a century, The Kashrut Authority is deeply committed to aiding clients on their kosher journey, helping to realise a profitable and long lasting market outlet for many and varied products. Accessing the kosher market offers a competitive edge, with vast potential on both a local and international scale. The Kashrut Authority believes in keeping the process simple, presenting a dedicated team and offering cutting edge technological solutions—The Kashrut Authority looks forward with confidence. 2 welCome n behalf of the entire KA Team, I am delighted to welcome O you to The Kashrut Authority, a dynamic organisation that has been instrumental in bringing kosher products to the people for more than a century. Our name, The Kashrut Authority, embodies who we are and what we do: kashrut is simply the Hebrew word for kosher, and we truly are authoritative experts in this field. Our KA logo is a proven trust–mark that consumers hold in the highest regard and we have extensive experience in helping clients with Kosher Certification for an incredible array of products. Our vast knowledge and experience in the kosher field helps each client on their kosher journey. Many of our clients have received KA Kosher Certification and, under the Kashrut Authority’s guidance, have been incredibly successful at both a local and global level. -

Thetorah -Com

6t9t2U2U I ne Paraoox oI Pesacn :inenr - | ne I oran.com TheTorah -com The Paradox of Pesach Sheni As a historical commemoration, Passover is tied to a specific date. Nevertheless, the Torah gives a make-up date for bringing the offering a month later. Gerim, non- Israelites living among Israelites as equals, are also allowed to bring this offering, even though it wasn)t their ancestors who were freed. How do we make sense of these anomalies? Prof. Steven Fraade u* ntrs .!i.aitrir! i'irir;ri{,r I t i I I 5* \} - A Fixed Lunar-Calendrical Commemoration: A fter explaining to Moses how the Israelites should perform the Passover I I ritual in order to avoid being killed during the plague of the firstborn, YHWH endswith: El? nll triri nin] T:rr ntDur ExodD:14 This day shallbe to you one of ;r:;r-! rf inx onirrlr firpr5 remembrance: you shall celebrate it as a hltns'//unrnrr thelnrah enm/artinlc/the-naradav-nf-nceanh-ehpni 1 111 6t9t2U2t) I he Paradox ot Pesach shent - | ne loran.com .r;lilT tr?i9 ni?l;| tr)!I-r1' festival to YHWH throughout the ages; you shall celebrate it as an institution for all time. Moses then passes the message along to the elders of Israel, expanding on this point: 'D:r' niDu' Exod'12:2t+ l?:Tn n$ trR"lDt?l You shall observe this as an .o?ip ru Tt;}'r! il4);'rrn institution for all time, for you and for ;'1):r' f':lqt? tli tNff '? i"l';r'l your descendants. -

Five Pillars of Orthodox Judaism Or Open Charedism by Rabbi Asher Lopatin

Five Pillars of Orthodox Judaism or Open Charedism by Rabbi Asher Lopatin You can be a good member, a wonderful, beloved and productive member of Anshe Sholom, and even an effective leader or officer, without holding of all these. But they are the principals which make us an Orthodox shul. I would hope that every member of our community struggle with them, think about them, and perhaps come up with interpretations or responses that work for their own lives. 1)Torah Mi Sinai – Torah shebichtav veTorah sheba’al peh – both the Oral and Written Tradition. The great liberal Orthodox thinker David Hartman openly declares he believes in this – but he then says that he believes in an interpretive tradition which is close to our second pillar. A great Conservative decisor, Rabbi Joel Roth, has said, “the halackic tradition is the given, and theology is required to fall into place behind it.” I believe our halachik tradition needs to be driven by theology in order to keep the tradition alive and infinite, rather than ossified and limited. We need to start with this awe of the Torah and Talmud coming from God and being infinite and deserving infinite reverence, placing ourselves humbly below it, and only then establishing ownership of it, and making it our “plaything” as King David says in Psalms. Only when a couple accepts Kiddushin can they become intimate with each other, and our rabbis compare Matan Torah to Kiddushin. Only if you feel the Torah is your God-given partner can you then become intimate with it, can you really feel you are so connected to it that you can make a conjecture as to what it is thinking, that you trust your instincts in interpreting it and its 3500 year tradition. -

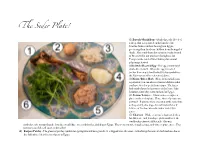

The Seder Plate

Te Seder Plate! (1) Zaroah/Shank Bone - Symbolizes the blood of a sheep that was painted on the lintels of the Israelite homes on their last night in Egypt, protecting their firstborn children from the angel of death. Also symbolizes the sacrifice for the festival of Passover that our ancestors brought to the Temple in the land of Israel during this annual pilgrimage festival. (2)Beitzah/Roasted Egg - The egg is round and symbolizes rebirth. When the egg is roasted (rather than simply hard boiled) it also symbolizes the Passover sacrifice referenced above. (3)Maror/Bitter Herb - Here, horseradish paste is pictured; you can also use horseradish root that you have sliced or peeled into strips. The bitter herb symbolizes the bitterness of the lives of the Israelites when they were enslaved in Egypt. (4) Potato/Lettuce - Often lettuce occupies a place on the seder plate. Here, slices of potato are pictured. If potato, these are eaten at the same time as the parsley, also dipped in salt water (6) or if lettuce, at the time when the bitter herb (3) is eaten. (5) Charoset - While everyone’s charoset looks a bit different - and Jewish people from all over the world make charoset differently - this mix symbolizes the mortar that the Israelites would have used with bricks, building in Egypt. This is often a mix of apples, nuts, and wine or grape juice. This sweetness is a beloved taste of the seder! (6) Karpas/Parsley - The green of parsley symbolizes springtime and new growth. It is dipped into salt water, symbolizing the tears of the Israelites due to the difficulty of their lives in slavery in Egypt.. -

Disordered Love: a Pesach Reader

Disordered Love: A Pesach Reader 18forty.org/articles/disordered-love-a-pesach-reader By: Yehuda Fogel For many people, and even more lecturers, the Seder night is a night of order. Many have the tradition to sing the order of the Seder, in what may offer its own slightly delightful commentary on life: order and discipline are not always poetic, but every once and a while we are able to make order itself sing. As Rabbi Avraham Yiztchak Kook put it: “Just as there are laws to poetry, there is poetry to laws.” This is one truth we discover on the Seder night. 1/3 But another truth we discover is that even within order, there is disorder. For all the talk of the order of the Seder night, there is a certain chaotic structure baked into the Haggadah itself. The sages argue about the construction of the text, and in our attempt to honor all perspectives, we are left with a complex, multi-layered Haggadah, one that shifts back and forth and back again from slavery to freedom to slavery to freedom. Some seek to dispel the anxiety of this disorder, with beautiful maps and guidelines to the order within it all. Yet others sip their wine and dribble Matzoh crumbs and wipe away wine stains from their pillow cases with a smile on their face. We support both (we really do!). In Rachel Sharansky Danziger’s words, at Tablet: We start the storytelling part of the Seder conventionally enough, with the words, “This is the bread of destitution that our ancestors ate in the land of Egypt.” But before we have time to settle into a third-person account of our ancestors’ story, we are made to say, “We were slaves to Pharaoh in the land of Egypt” in the first person. -

SEDER Activities 2014

SEDER Activities 2014 Assignments to Prepare in advance: a.What the seder means to me in 6 words. Deposit in basket and pull out. Someone reads it and others guess to who wrote it. b. Write up two questions each about Pesach ritual, about Exodus and about Judaism – one simple fact question and one one-ended thought question. Deposit in basket and ask child to pick out four. c. This is your journey: Freedom from and freedom to: From what this year have you freed yourself and toward what new goals have you progressed. d. Dayenu. What have you experiences where yopu were so grateful you said: Dayenu. This is so satisfying that it has made my life worthwhile and me overjoyed. f. Shifra and Puah Award. Pick story of resistance to tyranny like midwives. g. Bring prop to tell one episode of Exodus (like backback, boots, basket). Then arrange all props in order of episodes from Biblical tale and and ask each person to retell their part in order. h. Nahshon Award. When did I stand up or see someone stand up to show courage against conformity or take first step in difficult process. i. Miracle. When did I experience that I felt was miraculous in colloquial usage (not necessarily supernatural) j.Favorite Peach memory or most bizarre seder. k. Choose quote about freedom and slavery that you agree with. Read outloud. Why did you choose it? l. What part of haggadah gives a message you think relevant to the President or prime Minister for his next term? m. -

A Clergy Resource Guide

When Every Need is Special: NAVIGATING SPECIAL NEEDS IN A CONGREGATIONAL SETTING A Clergy Resource Guide For the best in child, family and senior services...Think JSSA Jewish Social Service Agency Rockville (Wood Hill Road), 301.838.4200 • Rockville (Montrose Road), 301.881.3700 • Fairfax, 703.204.9100 www.jssa.org - [email protected] WHEN EVERY NEED IS SPECIAL – NAVIGATING SPECIAL NEEDS IN A CONGREGATIONAL SETTING PREFACE This February, JSSA was privileged to welcome 17 rabbis and cantors to our Clergy Training Program – When Every Need is Special: Navigating Special Needs in the Synagogue Environment. Participants spanned the denominational spectrum, representing communities serving thousands throughout the Washington region. Recognizing that many area clergy who wished to attend were unable to do so, JSSA has made the accompanying Clergy Resource Guide available in a digital format. Inside you will find slides from the presentation made by JSSA social workers, lists of services and contacts selected for their relevance to local clergy, and tachlis items, like an ‘Inclusion Check‐list’, Jewish source material and divrei Torah on Special Needs and Disabilities. The feedback we have received indicates that this has been a valuable resource for all clergy. Please contact Rabbi James Kahn or Natalie Merkur Rose with any questions, comments or for additional resources. L’shalom, Rabbi James Q. Kahn, Director of Jewish Engagement & Chaplaincy Services Email [email protected]; Phone 301.610.8356 Natalie Merkur Rose, LCSW‐C, LICSW, Director of Jewish Community Outreach Email [email protected]; Phone 301.610.8319 WHEN EVERY NEED IS SPECIAL – NAVIGATING SPECIAL NEEDS IN A CONGREGATIONAL SETTING RESOURCE GUIDE: TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1: SESSION MATERIALS FOR REVIEW PAGE Program Agenda ......................................................................................................... -

OK Plant Manual Booklet

cxWs MANUAL FOR MANUFACTURING FACILITIES A Primer for Kosher Production Second Edition 2013 ~ KOSHER CERTIFICATION 391 Troy Avenue • Brooklyn, NY 11213 • USA Phone 718-756-7500 • Fax 718-756-7503 [email protected] • www.ok.org © ~ Kosher Certification. All rights will be strictly enforced. 2 OK Kosher Certification Mission Statement The ~ family is committed to all of its clients and to the kosher consumer. We are committed to upholding the standards of kosher law. We are committed to fast, high-quality service. We are committed to the use of state-of-the-art technology to streamline your kosher program. These commitments are evident at every stage of our relationship with our clients. The ~ uses its many resources and over 70 years of kosher certification experience to counsel companies regarding numerous kosher-related issues, including cost-effective production and ingredient alternatives, to better serve our customers. When issues do arise, we work with our customers to find acceptable solutions without compromising kosher standards. We believe that communication is essential to the effective development of a kosher program. To this end, we encourage our clients to ask questions. When you are unsure, ask the ~. If you are not sure if you should ask, then you should ask. When you are fairly sure, ask anyway. Our Rabbinic Coordinators prefer to answer twenty questions than to encounter one problem that results from a question not asked. Our Rabbinic Coordinators will answer your questions in a friendly and timely manner – they are here to serve you. This manual was prepared by our office staff and coordinated by Rabbi Levi Marmulszteyn. -

Descendants of Mayer Amschel Rothschild

Descendants of Hirsch (Hertz) ROTHSCHILD 1 Hirsch (Hertz) ROTHSCHILD d: 1685 . 2 Callmann ROTHSCHILD d: 1707 ....... +Gütle HÖCHST m: 1658 .... 3 Moses Callman BAUER ....... 4 Amschel Moses ROTHSCHILD ............. +Schönche LECHNICH m: 1755 .......... 5 Mayer Amschel ROTHSCHILD b: 23 February 1743/44 in Frankfurt am Main Germany d: 19 September 1812 in Frankfurt am Main Germany ................ +Guetele SCHNAPPER b: 23 August 1753 m: 29 August 1770 in Frankfurt am Main Germany d: 7 May 1849 Father: Mr. Wolf Salomon SCHNAPPER .............. 6 [4] James DE ROTHSCHILD b: 15 May 1792 in Frankfurt am Main Germany d: 15 November 1868 in Paris France .................... +[3] Betty ROTHSCHILD Mother: Ms. Caroline STERN Father: Mr. Salomon ROTHSCHILD ................. 7 [5] Gustave DE ROTHSCHILD b: 1829 d: 1911 .................... 8 [6] Robert Philipe DE ROTHSCHILD b: 19 January 1880 in Paris France d: 23 December 1946 .......................... +[7] Nelly BEER b: 28 September 1886 d: 8 January 1945 Mother: Ms. ? WARSCHAWSKI Father: Mr. Edmond Raphael BEER ....................... 9 [8] Alain James Gustave DE ROTHSCHILD b: 7 January 1910 in Paris France d: 1982 in Paris France ............................. +[9] Mary CHAUVIN DU TREUI ........................... 10 [10] Robert DE ROTHSCHILD b: 1947 .............................. 11 [11] Diane DE ROTHSCHILD .................................... +[12] Anatole MUHLSTEIN d: Abt. 1959 Occupation: Diplomat of Polish Government ................................. 12 [1] Anka MULHSTEIN ...................................... -

Palestinian and Israeli Literature.Pdf

Palestinian and Israeli Literature Prepared by: Michelle Ramadan, Pingree School This document has been made available online for educational purposes only. Use of any part of this document must be accompanied by appropriate citation. Parties interested in publishing any part of this document must received permission from the author. If you have any recommendations or suggestions for this unit, please do not hesitate to contact Michelle Ramadan at [email protected]. Overview: For many audiences, understanding of the PalestinianIsraeli conflict comes mainly from the media news of violence and of political friction dominate the airwaves, and we sometimes forget about the ordinary Palestinian and Israeli citizens involved. To get at the human element of the PalestinianIsraeli conflict, students will read, discuss, and reflect on stories from and/or about Palestine and Israel. Units are designed by theme/topic, and each unit contains readings from both Palestinian and Israeli perspectives on each theme/topic.This curriculum was designed for a grade 12 course. Timing: Suggested class periods: 21+. This curriculum may, of course, be shortened or lengthened depending on schedule, students, etc. This curriculum may also be developed into a semester long course. How to Read this Document: This Palestinian & Israeli Literature Unit has been divided into 9 miniunits. Under each miniunit, you will find suggested class times, background information or context, suggested readings, and suggested class lessons/activities. At the end of the document, you will find sample writing assignments and further information about the suggested readings. Most readings are available online, and links have been provided.