The Moon Landings: History, Politics, and Social Responsibility in Science by Melanie R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Victor Or Villain? Wernher Von Braun and the Space Race

The Social Studies (2011) 102, 59–64 Copyright C Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0037-7996 print / 2152-405X online DOI: 10.1080/00377996.2010.484444 Victor or Villain? Wernher von Braun and the Space Race JASON L. O’BRIEN1 and CHRISTINE E. SEARS2 1Education Department, University of Alabama in Huntsville, Huntsville, Alabama, USA 2History Department, University of Alabama in Huntsville, Huntsville, Alabama, USA Set during the Cold War and space race, this historical role-play focuses on Wernher von Braun’s involvement in and culpability for the use of slave laborers to produce V-2 rockets for Nazi Germany. Students will grapple with two central questions. Should von Braun have been allowed to emigrate to the United States given his affiliation with the Nazis and use of slave laborers? Should the U.S. government and military have put Braun in powerful positions in NASA and military programs? This activity encourages students to hone their critical thinking skills as they consider and debate a complex, multi-layered historical scenario. Students also have opportunity to articulate persuasive arguments either for or against von Braun. Each character sketch includes basic information, but additional references are included for teachers and students who want a more in depth background. Keywords: role-play, Wernher von Braun, Space Race, active learning Victor or Villain? Wernher von Braun and the Space Role-Playing as an Instructional Strategy Race By engaging in historical role-plays, students can explore In 2009, the United States celebrated the fortieth anniver- different viewpoints regarding controversial topics (Clegg sary of the Apollo 11 crew’s landing on the moon. -

50 Jahre Mondlandung« Mit Apollo-Astronaut Gefeiert Und Der VDI War Mit Dabei Am 29. Und 30. Mai 2019 Fanden Vor Großem Publ

»50 Jahre Mondlandung« mit Apollo-Astronaut gefeiert und der VDI war mit dabei Am 29. und 30. Mai 2019 fanden vor großem Publikum die Feierlichkeiten des 50jährigen Jubiläums der ersten bemannten Mondlandung in einzigartiger Kulisse im Technik Museum Speyer statt. Ein besonderer Ehrengast war der Apollo 16-Astronaut und »Moonwalker« Charles Duke. Die Deutsche Gesellschaft für Luft- und Raumfahrt (DGLR) veranstaltete am 29. Mai 2019 in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Deutschen Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt (DLR) und dem Technik Museum Speyer ein ganztägiges Fachsymposium mit dem Titel »First Moon Landing« in der beeindruckenden Kulisse Europas größter Raumfahrtausstellung »Apollo and Beyond«. 250 Fachbesucher nahmen an der mit »hochkarätigen« Referenten und Gästen aus der Raumfahrtbranche besetzten Fachveranstaltung teil. Die Referenten kamen aus den verschiedensten Bereichen der deutschen, europäischen, russischen und amerikanischen Raumfahrt. Gäste waren beispielsweise die deutschen Astronauten Reinhold Ewald, Matthias Maurer, Ulf Merbold, Ernst Messerschmid und Ulrich Walter. Der besondere Ehrengast war der trotz seiner 83 Jahre junggebliebene US-Astronaut Charles Duke, der als so genannter »Capcom«“ (Capsule Communicator) bei der ersten bemannten Mondlandung von Apollo 11 fungierte und später selbst als 10. und jüngster Mensch auf dem Mond mit Apollo 16 landete. Die Besucher/innen des Fachsymposiums verfolgten aufmerksam die Vorträge und hörten den Referenten gebannt zu (© DGLR/T. Henne) 1 Das Programm des Symposiums war aufgeteilt in vier -

Final Report of the Nazi War Crimes & Japanese

Nazi War Crimes & Japanese Imperial Government Records Interagency Working Group Final Report to the United States Congress April 2007 Nazi War Crimes and Japanese Imperial Government Records Interagency Working Group Final Report to the United States Congress Published April 2007 1-880875-30-6 “In a world of conflict, a world of victims and executioners, it is the job of thinking people not to be on the side of the executioners.” — Albert Camus iv IWG Membership Allen Weinstein, Archivist of the United States, Chair Thomas H. Baer, Public Member Richard Ben-Veniste, Public Member Elizabeth Holtzman, Public Member Historian of the Department of State The Secretary of Defense The Attorney General Director of the Central Intelligence Agency Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation National Security Council Director of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum Nationa5lrchives ~~ \T,I "I, I I I"" April 2007 I am pleased to present to Congress. Ihe AdnllniSlr:lllon, and the Amcncan [JeOplc Ihe Final Report of the Nazi War Crimes and Japanese Imperial Government Rcrords Interagency Working Group (IWG). The lWG has no\\ successfully completed the work mandated by the Nazi War Crimes Disclosure Act (P.L. 105-246) and the Japanese Imperial Government DisdoSUTC Act (PL 106·567). Over 8.5 million pages of records relaH:d 10 Japanese and Nazi "'ar crimes have been identifIed among Federal Go\emmelll records and opened to the pubhc. including certam types of records nevcr before released. such as CIA operational Iiles. The groundbrcaking release of Lhcse ft:cords In no way threatens lhe Malio,,'s sccurily. -

The Rise and Fall of Missiles in the Us Air Force, 1957-1967

FLAMEOUT: THE RISE AND FALL OF MISSILES IN THE U.S. AIR FORCE, 1957-1967 A Dissertation by DAVID WILLIAM BATH Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Joseph G. Dawson, III Committee Members, Terry H. Anderson Olga Dror Angela Pulley Hudson James Burk Head of Department, David Vaught December 2015 Major Subject: History Copyright 2015 David William Bath ABSTRACT This dissertation documents how the U.S. national perspective toward ballistic nuclear missiles changed dramatically between 1957 and 1967 and how the actions and attitudes of this time brought about long term difficulties for the nation, the Air Force, and the missile community. In 1957, national leaders believed that ballistic missiles would replace the manned bomber and be used to win an anticipated third world war between communist and capitalist nations. Only ten years later, the United States was deep into a limited war in Vietnam and had all but proscribed the use of nuclear missiles. This dissertation uses oral histories, memoirs, service school theses, and formerly classified government documents and histories to determine how and why the nation changed its outlook on nuclear ballistic missiles so quickly. The dissertation contends that because scientists and engineers created the revolutionary weapon at the beginning of the Cold War, when the U.S. and U.S.S.R. were struggling for influence and power, many national leaders urged the military to design and build nuclear ballistic missiles before the Soviet Union could do so. -

A Neorealist Analysis of International Space Politics (1957-2018)

“War in Space: Why Not?” A Neorealist Analysis of International Space Politics (1957-2018) Eirik Billingsø Elvevold Dissertação em Relações Internacionais Maio, 2019 Dissertação apresentada para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Relações Internacionais, realizada sob a orientação científica da Professora Doutora Ana Santos Pinto e a co-orientação científica do Mestre Rui Henrique Santos. ii To my wife Leyla, For your love, patience and support. iii AKNOWLEDGEMENTS As I came to Portugal to work for the Norwegian Embassy in Lisbon, I had no idea I would stay to study for several years. The decision, however, I will never regret. I would like to thank Universidade Nova and the social sciences faculty, FCSH, for allowing me to study at a leading university for International Relations in Portugal. Our classes, especially with prof. Tiago Moreira de Sa and prof. Carlos Gaspar, will always be remembered. To my coordinator, professor Ana Santos Pinto, I want to express gratitude for her guidance, sharp mind and patience throughout the process. The idea of studying a mix of international politics and space came with me from Norway to Portugal. After seeing Pinto teach in our scientific methods class, I asked her to be my coordinator. Even on a topic like space, where she admitted to having no prior expertise, her advice and thoughts were essential for me both academically and personally during the writing process. In addition, I want to express my sincere gratitude to Rui Henriques Santos for stepping in as my co- coordinator when professor Pinto took on other challenges at the Portuguese Ministry of Defense. -

The History of the America's Space Program

The History of the America’s Space Program By Matthew Behrens, the co-founder on the premise that the U.S. currently “The Soviet Union cannot attack the of Homes not Bombs and Toronto Ac- faces no major military competitor, the continental U.S. within the near fu- tion for Social Change is an organizer rapid U.S. build-up of nuclear arms fol- ture. It has no navy of importance of the Campaign to Stop Secret Trials lowing WWII was based on a similar and with a second-rate merchant ma- in Canada. understanding: the master of the globe rine, Soviet overseas operations gen- wanted to remain so forever. erally would be out of the question.” he proposal for National Mis- In a secret plan drafted two At the same time, the U.S. was sile Defence (and the various months after the atomic bombing of contemplating an all-out attack on the Tspace warfare programs into Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the U.S. ad- Soviets, who had lost more than 10% which it is designed to evolve), has a ministration of Harry Truman explored of their population during the war, it long, murky history that involves eve- the idea of launching 20 or 30 nuclear was also recruiting thousands of former ryone from Nazi war criminals and weapons against the USSR, even Nazi war criminals to work on its mili- power-crazed U.S. generals (who in- though: tary and space warfare programs. spired the film Dr. Strangelove) to weak-kneed U.S. Recruitment liberals who gave in to fears of Nazi Scientists and myths rather than op- As Christopher Simpson points pose the frightening plans of out, when the U.S. -

Air University Quarterly Review: Spring 1959 Volume. XI, Number 1

-fr ^CAíXl/^' Publislie d by Air University as tbe professional Journal of tlie In ited States Air Force The United States Air Force AIR UNIVERSITY QUARTERLY REVIEW Volume XI SPRING 1959 Number 1 THE EVOLUTION OF AIR L O G IST IC S................................................... 2 G en. E dwin W. R awlings, USAF BLUEPRINTS FOR SPACE................................................................................16 B rig. Gen. H omer A. B oushey, USAF DEVELOPMENT OF SPACE SUITS AND C A P SU L E S.................... 30 Dr . J ohn W. Heim and O tto Schueller THE PAST AND PRESENT OF SOVIET MILITARY D O C T R IN E ......................................................................................................38 Dr . K enneth R. W hiting EXPERIMENTAL STUDIES ON THE CONDITIONING OF MAN FOR SPACE F L I G H T .................................................................61 D r . B runo Balke SURPRISE IN THE MISSILE ERA ............................................................76 Lt . Col. R obert O. Brooks, U S A F A PREFACE TO ORGANIZATIONAL PA T TERN M A K IN G . 84 Col. R obert A. Shane, U S A F IN MY OPINION What Makes a Leader?..............................................................................105 Lt . Col. B. J . S mit h , USAF AIR FORCE REVIEW Operation Swiltlift— Peacetime Utilization of Air Reserve Forces..............................................................................109 Lt . Col. J affus M. Rodgers, U S A F BOOKS AND IDEAS Notes on Air Force Bibliography..........................................................113 Dr . R aymond Est ep Address manuscripts to Editor. Air Univrrsily Quarlerly Hrview, Headquartcrs Air Univcrsity, Max- Hell Air Force Base. Ala. Use of fuuds for printing this publication has bcen approved by the Secretary of the Air Force and the Director of the Bureau of the Budftct. -

The Immigration and Naturalization Service’S Failed Search for Nazi Collaborators in the United States, 1945-1979

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses July 2020 The Art of Not Seeing: The Immigration and Naturalization Service’s Failed Search for Nazi Collaborators in the United States, 1945-1979 Jeffrey Davis University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the European History Commons, Immigration Law Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Jeffrey, "The Art of Not Seeing: The Immigration and Naturalization Service’s Failed Search for Nazi Collaborators in the United States, 1945-1979" (2020). Masters Theses. 899. https://doi.org/10.7275/17306836 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/899 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Art of Not Seeing: The Immigration and Naturalization Service’s Failed Search for Nazi Collaborators in the United States, 1945-1979 A Thesis Presented by JEFFREY D. DAVIS Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2020 Department of History The Art of Not Seeing: The Immigration and Naturalization Service’s Failed Search for Nazi Collaborators in the United States, 1945-1979 A Thesis Presented by JEFFREY D. DAVIS Approved as to style and content by: ______________________________________ Jennifer Fronc, Chair ______________________________________ Andrew Donson, Member ______________________________________ Rebecca Hamlin, Member ______________________________________ Audrey L. -

Parker Launches 10> Sidemount Shuttles

SpaceFlight A British Interplanetary Society publication Volume 60 No.10 October 2018 £5.00 SUN seeker Parker launches 10> Sidemount Shuttles 634072 BIS launcher report 770038 Apollo 7 remembered 9 CONTENTS Features 11 Dr Parker’s Sun grazer NASA has embarked upon a new and more intensive data collection project designed to gather information about our Sun through direct sampling and a close-up look – far closer than ever before. 11 Letter from the Editor 16 Giant rockets: the third way Seradata analyst David Todd gives us his This month we remember the overview of how NASA could have acquired a flight of Apollo 7. Its real heavy-lifter a lot earlier and a whole lot cheaper, importance was not so much that it was the first manned Apollo had it taken a different route. mission but that it was upon its success that Apollo 8 was cleared 27 First up: Apollo 7 to fly to the Moon. In a way, this Fifty years ago in October, NASA launched the was a repeat of how Alan first manned Apollo mission, long in the making Shepard’s flight as the first and considerably changed from its original 16 American in space on 5 May 1961 objective. cleared the way for President Kennedy to announce the Moon 30 Getting there – the NLV project goal less than three weeks later. Robin Brand reports from the BIS Technical Few cannot fail to have been impressed with the launch of the Committee on the first phase of the Society’s Parker Solar Probe which will fly Nanosat Launch Vehicle project and describes closer to the Sun than any other how that activity is progressing. -

Intelligence, Reparations, and the US Army Air Forces, 1944-1947

Petrina, S. (2019). “Scientific Ammunition to Fire at Congress:” Intelligence, reparations and the US Army Air Forces, 1944-1947. Journal of Military History, 83(3), 795-829. “Scientific Ammunition to Fire at Congress:” Intelligence, Reparations, and the U.S. Army Air Forces, 1944-1947 "Secrets by the Thousands!" "Nazi Science Secrets!" "A Technological Treasure Hunt!" "All the war secrets, as released, are completely in the public domain." Military intelligence was not quite as accessible as it seemed to journalists in late 1946 and early 1947. This particular bounty of intelligence derived from extensive exploitation strategies hatched by American and British forces in the closing months of World War II (WWII). These efforts anticipated the Potsdam Conference and Agreement of July and August 1945, where Germany and the Nazi economy were carved up for postwar occupation and reparations. The largest was Operation LUSTY (LUftwaffe Secret TechnologY), launched by the United States (US) Army Air Forces (AAF) in 1944. LUSTY was a small army of engineers, scientists, AAF officers, and troops, numbering 3,000 at its peak in the summer of 1945. The task was no mystery, teams scoured the German countryside and cities, crating up over three million documents from Braunschweig targets alone. About 16,280 items and 6,200 tons of miscellaneous materiel and documents were shipped through London and Paris and back to Wright Field and Freeman Field in Ohio and Indiana in the first three of LUSTY's sixteen months of existence. Jets such as the Me-262 and Ju-290 were flown; He-162s, Ho-229s, Me-163s, V-2 rockets, and Ötztal's wind tunnels were shipped.1 For General Henry H. -

The Representation of International States, Societies, And

THE REPRESENTATION OF INTERNATIONAL STATES, SOCIETIES, AND CULTURES IN TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY SPACE-THEMED EXHIBITS: AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL INQUIRY INTO MUSEUMS IN CALIFORNIA, OREGON, WASHINGTON, AND BRITISH COLUMBIA ____________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Chico ____________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Anthropology Museum Studies Option ____________ by © William Robert Townsend 2017 Fall 2017 THE REPRESENTATION OF INTERNATIONAL STATES, SOCIETIES, AND CULTURES IN TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY SPACE-THEMED EXHIBITS: AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL INQUIRY INTO MUSEUMS IN CALIFORNIA, OREGON, WASHINGTON, AND BRITISH COLUMBIA A Thesis by William Robert Townsend Fall 2017 APPROVED BY THE INTERIM DEAN OF GRADUATE STUDIES: Sharon Barrios, Ph.D. APPROVED BY THE GRADUATE ADVISORY COMMITTEE: Georgia Fox, Ph.D. Georgia Fox, Ph.D., Chair Graduate Coordinator David Eaton, Ph.D. PUBLICATION RIGHTS No portion of this thesis may be reprinted or reproduced in any manner unacceptable to the usual copyright restrictions without the written permission of the author. iii DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis in memory of my grandmother, Elizabeth Ann Gerisch, for having taken me to Italy and, in doing so, inspiring my interest in cultural history. Grazie, nonna. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Foremost, I would like to thank my wonderful wife, Yaneli Torres Townsend, who has been by my side through the excitement, stress, and countless sleepless study- nights of both undergraduate and graduate school. Forever and always. I would also like to thank my amazing mom, Mary Ann Townsend, for always believing in me and for encouraging me to aim a little higher. As for my dad, Edward Townsend, thank you for taking me adventuring under the stars during our camping trips when I was young—our walks and philosophical conversations inspired my awe of the cosmos, and this thesis is undoubtedly an extension of that wonderment. -

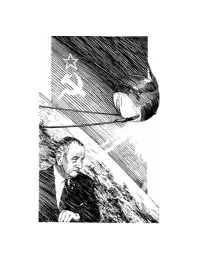

“Iwas at My Ranch in Texas,” Lyndon Baines Johnson Recalled

CHAPTER 1: October 1957 “I was at my ranch in Texas,” Lyndon Baines Johnson recalled, “when news of Sputnik flashed across the globe . and simultaneously a new era of history dawned over the world.” Only a few months earlier, in a speech delivered on June 8, Senator Johnson had declared that an intercontinental ballistic missile with a hydrogen warhead was just over the horizon. “It is no longer the disorderly dream of some science fiction writer. We must assume that our country will have no monopoly on this weapon. The Soviets have not matched our achievements in democracy and prosperity; but they have kept pace with us in building the tools of destruction.” 1 But those were only words, and Sputnik was a new reality. Shock, disbelief, denial, and some real consternation became epidemic. The impact of the successful launching of the Soviet satellite on October 4, 1957, on the American psyche was not dissimilar to the news of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Happily, the conse- quences of Sputnik were peaceable, but no less far-reaching. The United States had lost the lead in science and technology, its world leadership and preeminence had been brought into question, and even national security appeared to be in jeopardy. “This is a grim business,” Walter Lippman said, not because “the Soviets have such a lead in the armaments business that we may soon be at their mercy,” but rather because American society was at a moment of crisis and decision. If it lost “the momentum of its own progress, it will deteriorate and decline, lacking purpose and losing confidence in itself.” 2 According to the U.S.