Flèches and the Wounds of Reading

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Unlimited Responsibility of Spilling Ink Marko Zlomislic

ISSN 1393-614X Minerva - An Internet Journal of Philosophy 11 (2007): 128-152 ____________________________________________________ The Unlimited Responsibility of Spilling Ink Marko Zlomislic Abstract In order to show that both Derrida’s epistemology and his ethics can be understood in terms of his logic of writing and giving, I consider his conversation with Searle in Limited Inc. I bring out how a deconstruction that is implied by the dissemination of writing and giving makes a difference that accounts for the creative and responsible decisions that undecidability makes possible. Limited Inc has four parts and I will interpret it in terms of the four main concepts of Derrida. I will relate signature, event, context to Derrida’s notion of dissemination and show how he differs from Austin and Searle concerning the notion of the signature of the one who writes and gives. Next, I will show how in his reply to Derrida, entitled, “Reiterating the Differences”, Searle overlooks Derrida’s thought about the communication of intended meaning that has to do with Derrida’s distinction between force and meaning and his notion of differance. Here I will show that Searle cannot even follow his own criteria for doing philosophy. Then by looking at Limited Inc, I show how Derrida differs from Searle because repeatability is alterability. Derrida has an ethical intent all along to show that it is the ethos of alterity that is called forth by responsibility and accounted for by dissemination and difference. Of course, comments on comments, criticisms of criticisms, are subject to the law of diminishing fleas, but I think there are here some misconceptions still to be cleared up, some of which seem to still be prevalent in generally sensible quarters. -

Derrida in the University, Or the Liberal Arts in Deconstruction / C

Derrida in the University, or the Liberal Arts in Deconstruction / C. Kelly 49 CSSHE SCÉES Canadian Journal of Higher Education Revue canadienne d’enseignement supérieur Volume 42, No. 2, 2012, pages 49-66 Derrida in the University, or the Liberal Arts in Deconstruction Colm Kelly St. Thomas University ABSTRACT Derrida’s account of Kant’s and Schelling’s writings on the origins of the mod- ern university are interpreted to show that theoretical positions attempting to oversee and master the contemporary university find themselves destabilized or deconstructed. Two examples of contemporary attempts to install the lib- eral arts as the guardians and overseers of the contemporary university are examined. Both examples fall prey to the types of deconstructive displace- ments identified by Derrida. The very different reasoning behind Derrida’s own institutional intervention in the modern French university is discussed. This discussion leads to concluding comments on the need to defend pure re- search in the humanities, as well as in the social and natural sciences, rather than elevating the classical liberal arts to a privileged position. RÉSUMÉ Le compte-rendu de Derrida sur les écrits de Kant et de Schelling portant sur les origines de l’université moderne démontre que des positions théoriques tentant de surveiller et de gouverner l’université contemporaine se trouvent déstabilisées et déconstruites. L’auteur étudie deux exemples de tentatives contemporaines visant à donner aux arts libéraux le statut de gardiens et de surveillants de l’université contemporaine. Les deux exemples en question ne tiennent pas la route devant les substitutions déconstructives identifiées par Derrida. -

Derridean Deconstruction and Feminism

DERRIDEAN DECONSTRUCTION AND FEMINISM: Exploring Aporias in Feminist Theory and Practice Pam Papadelos Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Discipline of Gender, Work and Social Inquiry Adelaide University December 2006 Contents ABSTRACT..............................................................................................................III DECLARATION .....................................................................................................IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................V INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 1 THESIS STRUCTURE AND OVERVIEW......................................................................... 5 CHAPTER 1: LAYING THE FOUNDATIONS – FEMINISM AND DECONSTRUCTION ............................................................................................... 8 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 8 FEMINIST CRITIQUES OF PHILOSOPHY..................................................................... 10 Is Philosophy Inherently Masculine? ................................................................ 11 The Discipline of Philosophy Does Not Acknowledge Feminist Theories......... 13 The Concept of a Feminist Philosopher is Contradictory Given the Basic Premises of Philosophy..................................................................................... -

Derrida and the Singularity of Literature

DERRIDA AND THE SINGULARITY OF LITERATURE Jonathan Culler* In This Strange Institution Called Literature, an interview with Derek Attridge, Jacques Derrida offers an eloquent homage to literature: Experience of Being, nothing less, nothing more, on the edge of metaphysics, literature perhaps stands on the edge of everything, almost beyond everything, including itself. It’s the most interesting thing in the world, maybe more interesting than the world, and this is why, if it has no definition, what is heralded and refused under the name of literature cannot be identified with any other discourse. It will never be scientific, philosophical, conversational.1 This is a celebration of literature of a sort not much heard these days, when advanced critical approaches treat literature as one discourse among others, to privilege which would be an elitist mistake. In fact, this celebration of literature is not a privileging of some distinctiveness of literary language or of aesthetic achievement—literature, Derrida stresses, has no definition—but it nevertheless gives an importance to literary discourse, its engagement with the world, on the edge of the world, and the engagement that it calls forth in readers, which has the possibility to transform our literary culture. In a new book The Singularity of Literature, which is largely inspired by Derrida, Derek Attridge writes, “Derrida’s work over the past thirty-five years constitutes the most significant, far-reaching, and inventive exploration of literature for our time.”2 This is unmistakably true, though it is not widely recognized. One of the more grotesque aspects of the mediatic reception of Derrida in the United States is the idea that somehow Derrida’s work and deconstruction generally have constituted an attack on literature. -

Jacques Derrida Law As Absolute Hospitality

JACQUES DERRIDA LAW AS ABSOLUTE HOSPITALITY JACQUES DE VILLE NOMIKOI CRITICAL LEGAL THINKERS Jacques Derrida Jacques Derrida: Law as Absolute Hospitality presents a comprehensive account and understanding of Derrida’s approach to law and justice. Through a detailed reading of Derrida’s texts, Jacques de Ville contends that it is only by way of Derrida’s deconstruction of the metaphysics of presence, and specifi cally in relation to the texts of Husserl, Levinas, Freud and Heidegger, that the reasoning behind his elusive works on law and justice can be grasped. Through detailed readings of texts such as ‘To Speculate – on Freud’, Adieu, ‘Declarations of Independence’, ‘Before the Law’, ‘Cogito and the History of Madness’, Given Time, ‘Force of Law’ and Specters of Marx, de Ville contends that there is a continuity in Derrida’s thinking, and rejects the idea of an ‘ethical turn’. Derrida is shown to be neither a postmodernist nor a political liberal, but a radical revolutionary. De Ville also controversially contends that justice in Derrida’s thinking must be radically distinguished from Levinas’s refl ections on ‘the Other’. It is the notion of absolute hospitality – which Derrida derives from Levinas, but radically transforms – that provides the basis of this argument. Justice must, on de Ville’s reading, be understood in terms of a demand of absolute hospitality which is imposed on both the individual and the collective subject. A much needed account of Derrida’s infl uential approach to law, Jacques Derrida: Law as Absolute Hospitality will be an invaluable resource for those with an interest in legal theory, and for those with an interest in the ethics and politics of deconstruction. -

Habermas, Derrida and the Genre Distinction Between Fiction and Argument Sergeiy Sandler ([email protected]) International Studies in Philosophy 39 (4), 2007, Pp

Habermas, Derrida and the Genre Distinction between Fiction and Argument Sergeiy Sandler ([email protected]) International Studies in Philosophy 39 (4), 2007, pp. 103–119. The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity,1 published by Jürgen Habermas in 1985, was very soon recognized as a major contribution to the ongoing cultural debate around postmodernism.2 Within this book, the “Excursus on Leveling the Genre Distinction between Philosophy and Literature”3 occupies a central position. In what follows I will try to show that Habermas’s critique of Derrida in the Excursus in fact turns upon itself (which is not to imply that I necessarily side with Derrida in the debate at large). The Excursus polemically accuses Jacques Derrida, as suggested in its title, of leveling the genre distinction between philosophy and literature. By trying to ignore this genre distinction, claims Habermas, Derrida is trying to pull through a “radical critique of reason” without getting caught in the “aporia of self-referentiality”.4 He explains: There can only be talk about “contradiction” in the light of consistency requirements, which lose their authority or are at least subordinated to other demands – of an aesthetic nature, for example – if logic loses its conventional primacy over rhetoric.5 “Such discourses” – Habermas angrily notes in his concluding lecture in PDM – “unsettle the institutionalized standards of fallibilism; they always allow for a final word, even when the argument is already lost: that the opponent has committed a category mistake in the sorts of responses he has been making”.6 In the Excursus Habermas defends reason against this critique. -

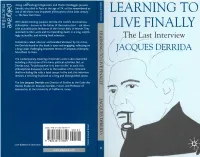

Learning to Live Finally Learning to Live Finally the Last Interview

ZJ ~T~} 'Along with Ludwig Wittgenstein and Martin Heidegger, Jacques Q, Qj Derrida, who died in Paris at the age of 74, will be remembered as —— one of the three most important philosophers of the 20th century.' LEARNING TO >*J — The New York Times r— ^-» With death looming, Jacques Derrida, the world's most famous __ *T\ philosopher - known as the father of 'deconstruction' - sat down ~' with journalist Jean Birnbaum of the French daily Le Monde. They LIVE FINALLY revisited his life's work and his impending death in a long, surpris• ingly accessible, and moving final interview. The Last Interview Sometimes called 'obscure' and branded 'abstruse' by his critics, the Derrida found in this book is open and engaging, reflecting on a long career challenging important tenets of European philosophy 'ACOUES DERRIDA from Plato to Marx. The contemporary meaning of Derrida's work is also examined, including a discussion of his many political activities. But, as Derrida says, 'To philosophize is to learn to die'; as such, this philosophical discussion turns to the realities of his imminent death-including life with a fatal cancer. In the end, this interview remains a touching final look at a long and distinguished career. The late Jacques Derrida was Director of Studies at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales, France, and Professor of Humanities at the University of California, Irvine. ISBN 978-0-230-53785-9 9 780230 537859 Cover illustration © Carol Hayes Learning to Live Finally Learning to Live Finally The Last Interview Jacques Derrida An Interview with Jean Birnbaum Translated by Pascale-Anne Brault and Michael Naas With a bibliography by Peter Krapp All rights reserved. -

As a Foreign Language: Rereading Deleuze and Derrida

Pan-Pacific Association of Applied Linguistics 12(1), 29-46 The Becoming-Philosophy as a Foreign Language: Rereading Deleuze and Derrida Immanuel Kim University of California, Riverside Kim, I. (2008). The becoming-philsophy as a foreign language: Rereading Deleuze and Derrida. Journal of Pan-Pacific Association of Applied Linguistics, 12(1), 29-46. This paper will revisit French theorists, Gilles Deleuze and Jacques Derrida, on the notion of the future of philosophy. Although their approaches to the future (devenir [to become] for Deleuze and á venir [to come] for Derrida) of philosophy may differ, I will argue that their differences allow for a space of congruence and continuity in the not only the field of philosophy but in every academic field. The question of the future of philosophy needs to be addressed because of the “crisis” that each academic department seems to face with every new faculty appointment, influx in student registration, applying for funding, etc. Each and every department in the university context seems to have the need to “justify” and validate the purpose of that discipline. I am not proposing another theory for theory’s sake, but a call to deeply reconsider and re-evaluate the philosophy of and in each department. After all, faculty members who are not even “involved” in the philosophy department still possess a PhD. Key Words: Deleuze, Derrida, philosophy 1 An Attempt to Find a Place for Philosophy Where does [philosophy] find today its most appropriate place? (Derrida, 2002, p.3) Where would we begin to reread these two thinkers? From what point should we begin? Would a rereading proffer an ethical reading of their respective philosophies? What can these thinkers offer to the field of linguistics? What relationship does philosophy (especially with these French thinkers) have with applied linguistics? What are the pragmatics of philosophy in the field research of applied linguistics? I will attempt to find a “place” where philosophy can enter even in the field of linguistics in order to iterate the importance of pragmatic research. -

July 12 “We Do Not Know What 'Being' Means. but Even If We Ask, 'What Is

July 12 “We do not know what ‘Being’ means. But even if we ask, ‘What is ‘Being’?’, we keep within an understanding of the ‘is’, though we are unable to fix conceptionally what that ‘is’ signifies.” (BT 25) explication, from explicare – Lat., to unfold (a term from the New Critics, an attempt to unfold the text from within itself, without outside context, having much in common with structuralism) aporia, logical contradiction, an “irreducible point” (even though contradictory, unresolvable). Important for Derrida as the point of deconstruction appears in a text. from Aristotle Physics IV Place [Space] (as such) is not matter, not form, not extension. Therefore, place is “the boundary of the containing body at which it is in contact with the contained body.” (IV.4) Place is somewhere but it is not in a place but “as the limit of the limited.” (IV.5) Time (as such) is not now, not movement, not really before and after (which are more spatial than temporal). Time elapses when we move from A to B, which are different “and [there is] some third thing is intermediate to them.” The now is a boundary.” That which perishes and becomes in time (in the same way that bodies come to be in space. (IV.10) Here are a few suggestions to focus your attention for next week’s reading, “Form and Meaning: A Note on the Phenomenology of Language”- (not reading “The Supplement of Copula”) Describe “form” as Derrida approaches and “defines” it in this essay. What problem does Derrida identify in Husserl’s methodology regarding expression and meaning? Why is it problematic? (problematic is not necessarily “bad”, just interesting) Esp. -

Violence and Life in the Work of Jacques Derrida and Theodor Adorno

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 6-2012 Critical ecologies: Violence and life in the work of Jacques Derrida and Theodor Adorno Richard L. Elmore II DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Elmore, Richard L. II, "Critical ecologies: Violence and life in the work of Jacques Derrida and Theodor Adorno" (2012). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 117. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/117 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEPAUL UNIVERSITY Chicago, Illinois CRITICAL ECOLOGIES: VIOLENCE AND LIFE IN THE WORK OF JACQUES DERRIDA AND THEODOR ADORNO A dissertation completed in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Rick Elmore 2011 Table of Contents 1. Table of Contents …………………………………………………………………. 2 2. Abstract ……………………………………………………………………………. 3 3. Introduction ……………………………………………………………………….. 4 4. Chapter One: Violence in the Work of Jacques Derrida……………………….. 13 i. Originary Reparations: The “Violence” Before “Violence”……. 14 ii. Lévi-Strauss and The Violence of Ethnocentrism ………………. 27 iii. Four Characteristics of Reparatory Violence …………………... 34 5. Chapter Two: Derrida and the Critique of Non-Violence ……………………... 43 i. Philosophy at the Threshold of Death: Levinas, Violence, and Subjectivity ………………………………………………………... 44 ii. -

Abbreviations

Abbreviations Note: I cite Derrida's works in parentheses in the body of the text, using the following system of abbreviations, referring first to the French and then, after the slash, to the English translation where such is available. I have adapted this system of abbreviations from the one that I first devised for The Prayers and Tears of facques Derrida (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997). AC L'autre cap. Paris: Editions de Minuit, 1991. Eng. trans. OH. AL facques Derrida: Acts of Literature. Ed. Derek Attridge. New York: Routledge, 1992. Circon. Circonfession: Cinquante-neuf periodes et periphrases. In Geoffrey Bennington and Jacques Derrida, facques Der rida. Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1991. Eng. trans. Circum . Circum. Circumfession: Fi~y-nine Periods and Periphrases. In Geof frey Bennington and Jacques Derrida, facques Derrida. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1993. DDP Du droit a la philosophie. Paris: Galilee, 1990. Eng. trans. Pp. 461-498: PR; pp. 577-618: "Sendoffs." DiT Difference in Translation. Ed. Joseph F. Graham. Ithaca, N. Y.: Cornell University Press, 198 5. OLE De l'esprit: Heidegger et la question. Paris: Galilee, 1987. Eng. trans. OS. OLG De la grammatologie. Paris: Editions de Minuit, 1967. Eng. trans. OG. OM "Donner la mort." In L'Ethique du don: facques Derrida et la pensee du don. Paris: Metailie-Transition, 1992. Eng. trans. GD. ONT Derrida and Negative Theology. Ed. Howard Coward and Toby Foshay. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1992. xiv ABBREVIATIONS DPJ Deconstruction and the Possibility of fustice. Ed. Drucilla Cornell et al. New York: Routledge, 1992. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Aristotle. (1941). Metaphysics, Physics. In The Basic Works of Aristotle. Richard McKeon. (Ed.). New York, NY: Random House. Attridge, Derek (Ed.). (1992). Acts of Literature. London and NY: Routledge. Augustine, St. (2006). Confessions. Indianapolis: Hackett. Bacon, Francis. (1960). The New Organon and Related Writings. New York: Prentice-Hall. Baker, Lynne Rudder. (2000). Metaphysics of Everyday Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Baldwin, Thomas. (2008). “Presence, Truth and Authenticity.” In S.Glendenning & R. Eaglestone. (Eds.), Derrida’s Legacies Literature and Philosophy (pp. 107-17). New York: Routledge. Bennington, Geoffrey. (2000). Interrupting Derrida. London: Routledge. Berman, Art. (1988).From the New Criticism to Deconstruction. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. Bernasconi, Robert. (1989). “Seeing Double: Destruktion and Deconstruction.” In D. Michelfelder (Ed.), Dialogue and Deconstruction The Gadamer-Derrida Encounter (pp. 233-50). Albany: SUNY Press. Brann, Eva T. H. (1991). The World of the Imagination. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. Caputo, John D. (1989). “Gadamer’s Closet Essentialism: A Derridean Critique.” In D. Michelfelder (Ed.), Dialogue and Deconstruction The Gadamer-Derrida Encounter (pp. 258-64). Albany: SUNY Press. ________. (1993). “In Search of the Quasi-Transcendental: The Case of Derrida and Rorty.” In G. Madison (Ed.). Working through Derrida (pp. 147-69). Evanston: Northwestern University Press. ________. (1997). Deconstruction in a Nutshell: A Conversation with Jacques Derrida. New York: Fordham University Press. Chalmers, David, D. Manley, R. Wasserman (Eds.). (2009). Metametaphysics New Essays on the Foundations of Ontology. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Churchland, Paul. (2013). Matter and Consciousness. 3rd. Ed. Cambridge: MIT Press. Cohen, Tom (Ed.). (2001). Jacques Derrida and the Humanities. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.