Edward Gibson Lanpher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 the Future Ira A

looking towards ANNUAL REPORT 2015 the future Ira A. Fulton Schools Of Engineering Dean Transcending Focusing on the Inspiring Pursuing Attracting Kyle Squires the student experience future use-inspired top traditional and student success engineers research faculty school of school of school of electrical, school for school of biological polytechnic campus sustainable computing, computer and engineering of and health systems School Director engineering informatics, and energy engineering matter, transport engineering Ann McKenna and the built decision systems School Director and energy School Director Air Traffic Management environment engineering Stephen M. Phillips School Director Marco Santello Air Transportation School Director School Director Photovoltaics Lenore Dai Medical diagnostics Management G. Edward Gibson, Jr. Ronald G. Askin Power and energy systems Personalized learning Rehabilitation Applied Science Biofuels Personalized learning Biosignatures discovery Engineering education Neuroengineering Environmental Resource Waste conversion to Educational gaming automation K-12 STEM Biomaterials and Management energy Energy-efficient data Wireless implantable Electrical energy storage therapeutics delivery Graphic Information Technology Public health-technology- storage and computing devices Thermal energy storage Synthetic and systems environment interactions Health informatics Sensors and signal and conversion biology Industrial and Organizational Psychology Microorganism-human Haptic interfaces processing Energy production Healthcare -

Spaceport News John F

Aug. 9, 2013 Vol. 53, No. 16 Spaceport News John F. Kennedy Space Center - America’s gateway to the universe MAVEN arrives, Mars next stop Astronauts By Steven Siceloff Spaceport News gather for AVEN’s approach to Mars studies will be Skylab’s Mquite different from that taken by recent probes dispatched to the Red Planet. 40th gala Instead of rolling about on the By Bob Granath surface looking for clues to Spaceport News the planet’s hidden heritage, MAVEN will orbit high above n July 27, the Astronaut the surface so it can sample the Scholarship Foundation upper atmosphere for signs of Ohosted a dinner at the what changed over the eons and Kennedy Space Center’s Apollo/ why. Saturn V Facility celebrating the The mission will be the first 40th anniversary of Skylab. The of its kind and calls for instru- gala featured many of the astro- ments that can pinpoint trace nauts who flew the missions to amounts of chemicals high America’s first space station. above Mars. The results are Six Skylab astronauts partici- expected to let scientists test pated in a panel discussion dur- theories that the sun’s energy ing the event, and spoke about slowly eroded nitrogen, carbon living and conducting ground- dioxide and water from the Mar- breaking scientific experiments tian atmosphere to leave it the aboard the orbiting outpost. dry, desolate world seen today. Launched unpiloted on May “Scientists believe the planet 14, 1973, Skylab was a complex CLICK ON PHOTO NASA/Tim Jacobs orbiting scientific laboratory. has evolved significantly over NASA’s Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution (MAVEN) spacecraft rests on a processing the past 4.5 billion years,” said stand inside Kennedy’s Payload Hazardous Servicing Facility Aug. -

Up from Kitty Hawk Chronology

airforcemag.com Up From Kitty Hawk Chronology AIR FORCE Magazine's Aerospace Chronology Up From Kitty Hawk PART ONE PART TWO 1903-1979 1980-present 1 airforcemag.com Up From Kitty Hawk Chronology Up From Kitty Hawk 1903-1919 Wright brothers at Kill Devil Hill, N.C., 1903. Articles noted throughout the chronology provide additional historical information. They are hyperlinked to Air Force Magazine's online archive. 1903 March 23, 1903. First Wright brothers’ airplane patent, based on their 1902 glider, is filed in America. Aug. 8, 1903. The Langley gasoline engine model airplane is successfully launched from a catapult on a houseboat. Dec. 8, 1903. Second and last trial of the Langley airplane, piloted by Charles M. Manly, is wrecked in launching from a houseboat on the Potomac River in Washington, D.C. Dec. 17, 1903. At Kill Devil Hill near Kitty Hawk, N.C., Orville Wright flies for about 12 seconds over a distance of 120 feet, achieving the world’s first manned, powered, sustained, and controlled flight in a heavier-than-air machine. The Wright brothers made four flights that day. On the last, Wilbur Wright flew for 59 seconds over a distance of 852 feet. (Three days earlier, Wilbur Wright had attempted the first powered flight, managing to cover 105 feet in 3.5 seconds, but he could not sustain or control the flight and crashed.) Dawn at Kill Devil Jewel of the Air 1905 Jan. 18, 1905. The Wright brothers open negotiations with the US government to build an airplane for the Army, but nothing comes of this first meeting. -

Skylab: the Human Side of a Scientific Mission

SKYLAB: THE HUMAN SIDE OF A SCIENTIFIC MISSION Michael P. Johnson, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: J. Todd Moye, Major Professor Alfred F. Hurley, Committee Member Adrian Lewis, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of History Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Johnson, Michael P. Skylab: The Human Side of a Scientific Mission. Master of Arts (History), May 2007, 115pp., 3 tables, references, 104 titles. This work attempts to focus on the human side of Skylab, America’s first space station, from 1973 to 1974. The thesis begins by showing some context for Skylab, especially in light of the Cold War and the “space race” between the United States and the Soviet Union. The development of the station, as well as the astronaut selection process, are traced from the beginnings of NASA. The focus then shifts to changes in NASA from the Apollo missions to Skylab, as well as training, before highlighting the three missions to the station. The work then attempts to show the significance of Skylab by focusing on the myriad of lessons that can be learned from it and applied to future programs. Copyright 2007 by Michael P. Johnson ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not be possible without the help of numerous people. I would like to begin, as always, by thanking my parents. You are a continuous source of help and guidance, and you have never doubted me. Of course I have to thank my brothers and sisters. -

Max M. Fisher Papers 185 Linear Feet (305 MB, 20 OS, 29 Reels) 1920S-2005, Bulk 1950S-2000

Max M. Fisher Papers 185 linear feet (305 MB, 20 OS, 29 reels) 1920s-2005, bulk 1950s-2000 Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI Finding aid written by Aimee Ergas, May 5, 2015. Accession Number: UP002350 Creator: Max M. Fisher Acquisition: This collection was deposited at the Reuther Library by the Max M. and Marjorie S. Fisher Foundation in August 2012. Language: Material entirely in English. Access: Collection is open for research. Items in vault are available at the discretion of the archives. Use: Refer to the Walter P. Reuther Library Rules for Use of Archival Materials. Notes: Citation style: “Max M. Fisher Papers, Box [#], Folder [#], Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University” Copies: Digital materials (29 disks) from the collection have been copied and transferred to the Reuther Library’s digital repository. Other Access Aids: Many photographs and information about Fisher available at www.maxmfisher.org. Related Material: Reuther Library collections: New Detroit, Inc. Records; Detroit Renaissance Records; materials in the Leonard N. Simons Jewish Community Archives, particularly the Jewish Federation of Metropolitan Detroit Records; Detroit Symphony Orchestra Hall, Inc., Records; Damon J. Keith Papers; Stanley Winkelman Papers; Mel Ravitz Papers; Wayne State University Archives, including Presidents’ Collections: David Adamany, Thomas N. Bonner, George E. Gullen, Irvin Reid. Audiovisual materials including photographs (boxes 291-308), videotapes (boxes 311-315), audiocassettes (boxes 316-319), CD and DVDS (boxes 319-320), minicassettes (box 321), a vinyl record (box 322), and audio reels (boxes 322-350) have been transferred to the Reuther’s Audiovisual Department Two boxes of signed letters from U.S. -

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project MORTON R. DWORKEN, JR. Interviewed

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project MORTON R. DWORKEN, JR. Interviewed by: Ambassador (ret.) Raymond Ewing Initial interview date: March 10, 008 Copyright 013 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in ashington, D.C. $ raised in Ohio. Yale University$ (ohns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) ,ntered the Foreign Service in 19.8 A0111 Course FSI2 3ietnam Training Center, Arlington, 3A. 19.8019.9 Course of instruction Fort Bragg (F4 Special arfare School 3ietnamese language study Taipei, Taiwan$ International Rice Institute$ New 8ife 19.9 Development Officer Training Rice production Saigon, 3ietnam2 9ilitary Assistance Command Civil Operations 19.9 9ilitary Assistance Command Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support (9AC3CORDS) Province supervisory team training Phuoc 8ong, 3ietnam2 9ember, Provincial Advisory Team 19.901971 Province description 9RIII (Third Corps Tactical Zone) Team composition Ambassador Charlie hitehouse Ambassador Richard Funkhouser 8t. Colonel Bob Hayden Operations Transport 8ocal security programs Refugees 3iet Cong village chief 1 8iving conditions 3isits to Saigon Personal weapons 9ontagnards Assistance to Catholic Sisters Rattan production Hamlet ,valuation System (H,S) Tet Province Development Plan Relations with 3ietnamese army Hawthorne (Hawk) 9ills Ambassador Sam Berger General Abrams Counter0Insurgency Assessment of US03ietnam endeavor 3ientiane, 8aos2 Special Assistant for Political09ilitary Affairs 197101973 Nickname2 -

SKYLAB the FORGOTTEN MISSIONS a Senior Honors Thesis

SKYLAB THE FORGOTTEN MISSIONS A Senior Honors Thesis by MICHAEL P. IOHNSON Submitted to the Office of Honors Programs 4 Academic Scholarships Texas ARM University In partial fulfillment of the requirements of the UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH FELLOWS April 2004 Major: History SKYLAB THE FORGOTTEN MISSIONS A Senior Honors Thesis by MICHAEL P. JOHNSON Submitted to the Office of Honors Programs & Academic Scholarships Texas A&M University In partial fulfillment of the requirements of the UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH FELLOW Approved as to style and content by: Jonathan C pers ith Edward A. Funkhouser (Fellows dv' or) (Executive Director) April 2004 Major: History ABSTRACT Skylab The Forgotten Missions. (April 2004) Michael P. Johnson Department of History Texas A&M University Fellows Advisor: Dr. Jonathan Coopersmith Department of History The Skylab program featured three manned missions to America's first and only space station from May 1973 to February 1974. A total of nine astronauts, including one scientist each mission, flew aboard the orbital workshop. Since the Skylab missions contained major goals including science and research in the space environment, the majority of publications dealing with the subject focus on those aspects. This thesis intends to focus, rather, on the human elements of the three manned missions. By incorporating not only books, but also oral histories and interviews with the actual participants, this work contains a more holistic approach and viewpoint. Beginning with a brief history of the development of a space station, this document also follows the path of the nine astronauts to their acceptance into the program. Descriptions of the transition period for NASA from the Moon to a space station, a discussion on the main events of all the missions, and finally a look at the transition to the new space shuttle comprise a major part of the body. -

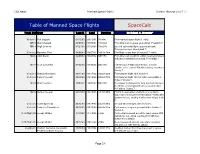

Table of Manned Space Flights Spacecalc

CBS News Manned Space Flights Current through STS-117 Table of Manned Space Flights SpaceCalc Total: 260 Crew Launch Land Duration By Robert A. Braeunig* Vostok 1 Yuri Gagarin 04/12/61 04/12/61 1h:48m First manned space flight (1 orbit). MR 3 Alan Shepard 05/05/61 05/05/61 15m:22s First American in space (suborbital). Freedom 7. MR 4 Virgil Grissom 07/21/61 07/21/61 15m:37s Second suborbital flight; spacecraft sank, Grissom rescued. Liberty Bell 7. Vostok 2 Guerman Titov 08/06/61 08/07/61 1d:01h:18m First flight longer than 24 hours (17 orbits). MA 6 John Glenn 02/20/62 02/20/62 04h:55m First American in orbit (3 orbits); telemetry falsely indicated heatshield unlatched. Friendship 7. MA 7 Scott Carpenter 05/24/62 05/24/62 04h:56m Initiated space flight experiments; manual retrofire error caused 250 mile landing overshoot. Aurora 7. Vostok 3 Andrian Nikolayev 08/11/62 08/15/62 3d:22h:22m First twinned flight, with Vostok 4. Vostok 4 Pavel Popovich 08/12/62 08/15/62 2d:22h:57m First twinned flight. On first orbit came within 3 miles of Vostok 3. MA 8 Walter Schirra 10/03/62 10/03/62 09h:13m Developed techniques for long duration missions (6 orbits); closest splashdown to target to date (4.5 miles). Sigma 7. MA 9 Gordon Cooper 05/15/63 05/16/63 1d:10h:20m First U.S. evaluation of effects of one day in space (22 orbits); performed manual reentry after systems failure, landing 4 miles from target. -

Early Years: Mercury to Apollo-Soyuz the Early Years: Mercury to Apollo-Soyuz

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Infor␣ mat␣ ion Summar␣ ies PMS 017-C (KSC) September 1991 The Early Years: Mercury to Apollo-Soyuz The Early Years: Mercury to Apollo-Soyuz The United States manned space flight effort has NASA then advanced to the Mercury-Atlas series of progressed through a series of programs of ever orbital missions. Another space milestone was reached increasing scope and complexity. The first Mercury launch on February 20, 1962, when Astronaut John H. Glenn, from a small concrete slab on Complex 5 at Cape Jr., became the first American in orbit, circling the Earth Canaveral required only a few hundred people. The three times in Friendship 7. launch of Apollo 11 from gigantic Complex 39 for man’s On May 24, 1962, Astronaut N. Scott Carpenter in first lunar landing engaged thousands. Each program Aurora 7 completed another three-orbit flight. has stood on the technological achievements of its Astronaut Walter N. Schirra, Jr., doubled the flight predecessor. The complex, sophisticated Space Shuttle time in space and orbited six times, landing Sigma 7 in a of today, with its ability to routinely carry six or more Pacific recovery area. All prior landings had been in the people into space, began as a tiny capsule where even Atlantic. one person felt cramped — the Mercury Program. Project Mercury Project Mercury became an official program of NASA on October 7, 1958. Seven astronauts were chosen in April, 1959, after a nationwide call for jet pilot volunteers. Project Mercury was assigned two broad missions by NASA-first, to investigate man’s ability to survive and perform in the space environment; and second, to develop the basic space technology and hardware for manned spaceflight programs to come. -

Marshall Space Flight Center, Building No. 4705) Redstone,Arsenal Apollo Road Huntsville Vicinity Madison County > Alabama 7B

MARSHALL SPACE FLIGHT CENTER, HAER No. AL-129-B NEUTRAL BUOYANCY SIMULATOR FACILITY (Marshall Space Flight Center, Building No. 4705) Redstone,Arsenal Apollo Road Huntsville Vicinity Madison County > Alabama 7B- BLACK & WHITE PHOTOGRAPHS HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD National Park Service Department of the Interior P.O. Box 37 3 77 Washington, DC 20013-7127 ADDENDUM TO: HAER AL-129-B MARSHALL SPACE FLIGHT CENTER, NEUTRAL BUOYANCY ALA,45-HUVI.VJB- SIMULATOR FACILITY (Building No. 4705) Redstone Arsenal Rideout Road Huntsville vicinity Madison County Alabama WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA REDUCED COPIES OF MEASURED DRAWINGS FIELD RECORDS HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 1849 C Street NW Washington, DC 20240-0001 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINNERING RECORD NEUTRAL BUOYANCY SIMULATOR (NBS) FACILITY HAERNo.AL-129-B Location: Building 4705, George C. Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville vicinity, Madison County, Alabama Date of construction: 1968. 1979 Builder: Marshall Space Flight Center Present owner: National Aeronautics and Space Administration Present use: Not in operation Significance: The Neutral Buoyancy Simulator (NBS) was NASA's first large, water-filled tank designed and built to create on Earth an experience very close to the weightless condition astronauts experienced when working in space. When properly weighted to compensate for their buoyancy, test engineers and astronauts in spacesuits were "neutrally buoyant," a condition closely simulating that of space. Various objects were buoyed or weighted to make them neutrally buoyant as well. The NBS was large enough to accommodate full-size mockups of space hardware and structures submerged within it. Results of tests in the NBS confirmed engineering designs and procedures, and astronauts initially practiced mission maneuvers there as well. -

ESPERANCE MUSEUM PO Box 507 Esperance WA 6450

ESPERANCE MUSEUM PO Box 507 Esperance WA 6450 (08) 9083 1580 [email protected] www.esperance.wa.gov.au/museum Skylab was America’s first space station and the world’s first big space station. Skylab could be considered the largest single recycling project ever, as the station itself was made from leftover Saturn 5 and Apollo hardware components. It consisted of five modules: • Orbital Workshop - the living and working area for the crew. • Airlock Module - used by the Astronauts to access the outside of Skylab for space walks. • Apollo Telescope Mount (ATM) - attached to one end of the cylindrical workshop. It was used to study our sun, stars and earth with no atmospheric interference. • Multiple Docking Adapter - allowed more than one Apollo spacecraft to dock to the station at once. • The Saturn Instrument Unit (IU) - used by NASA teams in Huntsville to reprogram the space station using a massive ring of computers. The unit was used to guide Skylab itself into orbit. IU also controlled the jettisoning of the protective payload shroud and activated the on-board life support systems, started the solar inertial attitude maneuver, deployed the Apollo Telescope mount at a 90-degree angle and deployed Skylab’s solar wings. This illustration shows general characteristics of the Skylab with call- outs of its major components. Credit: NASA Esperance Museum (2019) Page 2 What was it like? Skylab was big! About 36 meters long, 6.7 meters wide and weighed 90.6 tonnes. Its large interior volume made Skylab spacious and crew had freedom to move A wire mesh grid separated the interior into a workshop and living quarters, making it the first two-storey space habitat in space. -

Defining the Goals for Future Human Space Endeavors Is a Challenge Now Facing All Spacefaring Nations

- 1 - Chapter 22 LIFE SUPPORT AND PERFORMANCE ISSUES FOR EXTRAVEHICULAR ACTIVITY (EVA) Dava Newman, Ph.D. and Michael Barratt, M.D. 22.1 Introduction Defining the goals for future human space endeavors is a challenge now facing all spacefaring nations. Given the high costs and associated risks of sending humans into Earth orbit or beyond – to lunar or Martian environments, the nature and extent of human participation in space exploration and habitation are key considerations. Adequate protection for humans in orbital space or planetary surface environments must be provided. The Space Shuttle, Mir Space Station, Salyut-Soyuz, and Apollo programs have proven that humans can perform successful extravehicular activity (EVA) in microgravity and on the Lunar surface. Since the beginning of human exploration above and below the surface of the Earth, the main challenge has been to provide the basic necessities for human life support that are normally provided by nature. A person subjected to the near vacuum of space would survive only a few minutes unprotected by a spacesuit. Body fluids would vaporize without a means to supply pressure, and expanded gas would quickly form in the lungs and other tissues, preventing circulation and respiratory movements. EVA is a key and enabling operational resource for long- duration missions which will establish human presence beyond the Earth into the solar system. In this chapter, EVA is used to describe space activities in which a crew member leaves the spacecraft or base and is provided life support by the spacesuit. To meet the challenge of EVA, many factors including atmosphere composition and pressure, thermal control, radiation protection, human performance, and other areas must be addressed.