Warithuddin Muhammad and Muslim Identity in the Nation of Islam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism

Journal of Education & Social Policy Vol. 1 No. 1; June 2014 Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism Shahida Bilqies Research Scholar, Shah-i-Hamadan Institute of Islamic Studies University of Kashmir, Srinagar-190006 Jammu and Kashmir, India. Sufism, being the marrow of the bone or the inner dimension of the Islamic revelation, is the means par excellence whereby Tawhid is achieved. All Muslims believe in Unity as expressed in the most Universal sense possible by the Shahadah, la ilaha ill’Allah. The Sufi has realized the mysteries of Tawhid, who knows what this assertion means. It is only he who sees God everywhere.1 Sufism can also be explained from the perspective of the three basic religious attitudes mentioned in the Qur’an. These are the attitudes of Islam, Iman and Ihsan.There is a Hadith of the Prophet (saw) which describes the three attitudes separately as components of Din (religion), while several other traditions in the Kitab-ul-Iman of Sahih Bukhari discuss Islam and Iman as distinct attitudes varying in religious significance. These are also mentioned as having various degrees of intensity and varieties in themselves. The attitude of Islam, which has given its name to the Islamic religion, means Submission to the Will of Allah. This is the minimum qualification for being a Muslim. Technically, it implies an acceptance, even if only formal, of the teachings contained in the Qur’an and the Traditions of the Prophet (saw). Iman is a more advanced stage in the field of religion than Islam. It designates a further penetration into the heart of religion and a firm faith in its teachings. -

Islamic Calendar from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Islamic calendar From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia -at اﻟﺘﻘﻮﻳﻢ اﻟﻬﺠﺮي :The Islamic, Muslim, or Hijri calendar (Arabic taqwīm al-hijrī) is a lunar calendar consisting of 12 months in a year of 354 or 355 days. It is used (often alongside the Gregorian calendar) to date events in many Muslim countries. It is also used by Muslims to determine the proper days of Islamic holidays and rituals, such as the annual period of fasting and the proper time for the pilgrimage to Mecca. The Islamic calendar employs the Hijri era whose epoch was Islamic Calendar stamp issued at King retrospectively established as the Islamic New Year of AD 622. During Khaled airport (10 Rajab 1428 / 24 July that year, Muhammad and his followers migrated from Mecca to 2007) Yathrib (now Medina) and established the first Muslim community (ummah), an event commemorated as the Hijra. In the West, dates in this era are usually denoted AH (Latin: Anno Hegirae, "in the year of the Hijra") in parallel with the Christian (AD) and Jewish eras (AM). In Muslim countries, it is also sometimes denoted as H[1] from its Arabic form ( [In English, years prior to the Hijra are reckoned as BH ("Before the Hijra").[2 .(ﻫـ abbreviated , َﺳﻨﺔ ﻫِ ْﺠﺮﻳّﺔ The current Islamic year is 1438 AH. In the Gregorian calendar, 1438 AH runs from approximately 3 October 2016 to 21 September 2017.[3] Contents 1 Months 1.1 Length of months 2 Days of the week 3 History 3.1 Pre-Islamic calendar 3.2 Prohibiting Nasī’ 4 Year numbering 5 Astronomical considerations 6 Theological considerations 7 Astronomical -

Women Islamic Scholars, Theological Seminaries.18 Similar to the Muftis, and Judges Are the Great Exception

ISSUE BRIEF 10.02.18 Women as Religious Authorities: What A Forgotten History Means for the Modern Middle East Mirjam Künkler, Ph.D., University of Göttingen Although the history of Islam includes family members of the prophet were numerous examples of women transmitting frequently consulted on questions of Islamic hadith (i.e., sayings of the prophet), writing guidance. This practice was not limited to authoritative scholarly commentaries on the prophet’s family and descendants. As the Quran and religious law, and issuing Islamic scholar Khaled Abou El Fadl notes, fatwas (rulings on questions of Islamic law), “certain families from Damascus, Cairo, and women rarely perform such actions today. Baghdad made a virtual tradition of training Most Muslim countries, including those in female transmitters and narrators, and… the Middle East, do not allow women to these female scholars regularly trained serve as judges in Islamic courts. Likewise, and certified male and female jurists and few congregations would turn to women therefore played a major contributing role for advice on matters of Islamic law, or in the preservation and transmission of invite women to lead prayer or deliver the Islamic traditions.”1 sermon (khutba). Women’s role in transmitting hadiths For decades, Sudan and Indonesia were was modeled after ‘A’ishah, the prophet’s the only countries that permitted female youngest wife, who had been such a prolific judges to render decisions on the basis of transmitter that Muhammad is said to have the Quran and hadiths (which are usually told followers they would receive “half their conceived as a male prerogative only). -

BILAL, the FIRST MUEZZIN a MUSLIM STORY Key Ideas

BILAL, THE FIRST MUEZZIN A MUSLIM STORY Key Ideas: Islam, the call to prayer, courage Bilal stood on top of the Ka’aba in Mecca. It had been a difficult and dangerous thing to do, but he had a far more important task to complete. He filled his lungs with as much air as he could, then used his deep and powerful voice to call faithful Muslims to prayer. Allah is the greatest. I bear witness that there is no god but Allah. I bear witness that Muhammad is Allah’s messenger. Come to prayer. Come to salvation. There is no God but Allah. Even Bilal could not believe how his life had changed to bring him to this point. Bilal was born in Arabia, but he was a slave. His parents had been black Africans who had also lived as slaves, so their son had to be a slave too. When he was old enough, he was taken to the market place and sold to a new master. Umaya owned Bilal. He was a merchant, who made a good living from selling idols in Mecca. He had a number of slaves, and treated them badly, for slaves were cheap, and Umaya had plenty of money. When the merchant heard Muhammad teaching about one god, Allah, he was angry. He might lose money. But when he heard Muhammad say that all people were equal, like the teeth in a comb, he was furious. No slave was equal to him. The merchant decided to test Muhammad’s teachings. He ordered Bilal to strike one of the Prophet’s companions, firmly believing that a slave would not disobey his master. -

'Din Al-Fitrah' According to Al-Faruqi and His Understandings About

‘Din Al-Fitrah’ According To al-Faruqi and His Understandings about Religious Pluralism Mohd Sharif, M. F., Ahmad Sabri Bin Osman To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i3/3991 DOI:10.6007/IJARBSS/v8-i3/3991 Received: 27 Feb 2018, Revised: 20 Mar 2018, Accepted: 28 Mar 2018 Published Online: 30 Mar 2018 In-Text Citation: (Mohd Sharif & Osman, 2018) To Cite this Article: Mohd Sharif, M. F., & Osman, A. S. Bin. (2018). “Din Al-Fitrah” According To al-Faruqi and His Understandings about Religious Pluralism. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 8(3), 689–701 Copyright: © 2018 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Vol. 8, No. 3, March 2018, Pg. 689 – 701 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJARBSS JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 8 , No.3, March 2018, E-ISSN: 2222-6990 © 2018 HRMARS ‘Din Al-Fitrah’ According To al-Faruqi and His Understandings about Religious Pluralism Mohd Sharif, M. -

Muhammad, Sultan 1

Muhammad, Sultan 1 Sultan Muhammad Oral History Interview Thursday, February 28, 2019 Interviewer: This is an interview with Sultan Muhammad as part of the Chicago History Museum Muslim Oral History Project. The interview is being conducted on Thursday, February 28, 2019 at 3:02 pm at the Chicago History Museum. Sultan Muhammad is being interviewed by Mona Askar of the Chicago History Museum’s Studs Terkel Center for Oral History. Could you please state and spell your first and last name? Sultan Muhammad: My name is Sultan Muhammad. S-u-l-t-a-n Last name, Muhammad M-u-h-a-m-m-a-d Int: When and where were you born? SM: I was born here in Chicago in 1973. In the month of January 28th. Int: Could you please tell us about your parents, what they do for a living. Do you have any siblings? SM: My father, may blessings be on him, passed in 1990. He was also born here in Chicago. He is a grandson of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad. He grew up in the Nation of Islam, working for his father, Jabir Herbert Muhammad who was the fight manager for Muhammad Ali and business manager of the Nation of Islam. Sultan Muhammad, my father, was also a pilot. He was the youngest black pilot in America at the time. Later he became an imam under Imam Warith Deen Mohammed after 1975. My mother, Jamima was born in Detroit. She is the daughter of Dorothy Rashana Hussain and Mustafa Hussain. Robert was his name before accepting Islam. -

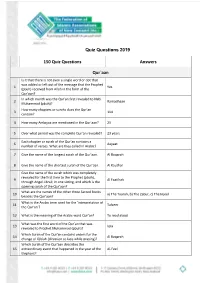

Quiz Questions 2019

Quiz Questions 2019 150 Quiz Questions Answers Qur`aan Is it that there is not even a single word or dot that was added or left out of the message that the Prophet 1 Yes (pbuh) received from Allah in the form of the Qur’aan? In which month was the Qur’an first revealed to Nabi 2 Ramadhaan Muhammad (pbuh)? How many chapters or surahs does the Qur’an 3 114 contain? 4 How many Ambiyaa are mentioned in the Qur’aan? 25 5 Over what period was the complete Qur’an revealed? 23 years Each chapter or surah of the Qur’an contains a 6 Aayaat number of verses. What are they called in Arabic? 7 Give the name of the longest surah of the Qur’aan. Al Baqarah 8 Give the name of the shortest surah of the Qur’aan. Al Kauthar Give the name of the surah which was completely revealed for the first time to the Prophet (pbuh), 9 Al Faatihah through Angel Jibrail, in one sitting, and which is the opening surah of the Qur’aan? What are the names of the other three Sacred Books 10 a) The Taurah, b) The Zabur, c) The Injeel besides the Qur’aan? What is the Arabic term used for the ‘interpretation of 11 Tafseer the Qur’an’? 12 What is the meaning of the Arabic word Qur’an? To read aloud What was the first word of the Qur’an that was 13 Iqra revealed to Prophet Muhammad (pbuh)? Which Surah of the Qur’an contains orders for the 14 Al Baqarah change of Qiblah (direction to face while praying)? Which Surah of the Qur’aan describes the 15 extraordinary event that happened in the year of the Al-Feel Elephant? 16 Which surah of the Qur’aan is named after a woman? Maryam -

ALI RIZA DEMIRCAN.Indd

INDEX FOREWORD CHAPTER ONE: SEXUAL EDUCATION IS FARD (MANDATORY) CHAPTER TWO: SEXUAL LIFE IS PART OF A LIFE OF WORSHIP CHAPTER THREE: SEXUALITY AND THE ISLAMIC REALITY, WHICH PRESIDES OVER SEXUAL LIFE CHAPTER FOUR: IT IS FORBIDDEN TO ABANDON SEXUAL LIFE CHAPTER FIVE: MARRIAGE IS AN INNATE NEED AND RELIGIOUS OBLIGATION CHAPTER SIX: THE ROLES OF SEXUAL PLEASURE CHAPTER SEVEN: SEXUAL PROHIBITIONS BETWEEN SPOUSES AND EXPIATION FOR HARAM BEHAVIOR CHAPTHER EIGHT: GUIDING RULES ON SEXUAL RELATIONS IN MARRIAGE AND GHUSL CHAPTHER NINE: SEXUAL DEFECTS, ILLNESSES, AND OTHER ISSUES THAT INVALIDATE MARRIAGE CHAPTER TEN: SEXUAL ISSUES IN MARRIAGE, DIVORCE, AND IDDAH CHAPTER ELEVEN: JEALOUSY CHAPTER TWELVE: HARAM SEXUAL ACTS CHAPTER THIRTEEN: PENALTIES FOR SEXUAL CRIMES CHAPTER FOURTEEN: POLYGAMY (Ta’addud Al-Zawajat) CHAPTER FIFTEEN: PROPHET MUHAMMAD’S MARRIAGES CHAPTER SIXTEEN: Concubines and Their Sexual Exploitation CHAPTER SEVENTEEN: SEXUAL LIFE IN HEAVEN ABBREVIATIONS: BIBLIOGRAPHY: ABOUT THE AUTHOR: 2 ABBREVIATIONS: Ibid. : (Latin, short for ibidem, meaning the same place) Avnul-Mabud: Avnul-Mabud SHerh-u Sunen-i Ebi Davud B. Meram : Buluğul-Meram min Edilletil-Ahkam El- Jami’us Sagir: el-Jamius-Sagir Fi Ehadisil-Beshirin-Nezir. Et-Tac: et-Tac el-Camiu lil-Usul Fi Ehadisir Resul. Feyzul Kadir: Faidul-Qadir Sherhul-Camius-Sagir. Hn: Hadith Number. Husnul-Ustevi: Husnul-Usveti Bima Sebete Minellahi ve Resulihi Fin-Nisveti. H. İ. ve İ.F. Kamusu: Hukuk-u Islamiyye ve Istilahat-i Fikhiyye Dictionary Ibn-i Mace: Sunnen-i Ibn-i Mace. I.Kesir : Tefsirul-Kur’anil-Azim. B. : Book K. Hafa : Kesful Hafa ve Muzlul-Iibas Ammeshtehere Minel-Ehadisi Ala Elsinetin Nasi. M. -

The Intentional Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq As a Violation Of

The Intentional Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq as a Violation of Human Rights Submission for the United Nations Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights About us RASHID International e.V. is a worldwide network of archaeologists, cultural heritage experts and professionals dedicated to safeguarding and promoting the cultural heritage of Iraq. We are committed to de eloping the histor! and archaeology of ancient "esopotamian cultures, for we belie e that knowledge of the past is ke! to understanding the present and to building a prosperous future. "uch of Iraq#s heritage is in danger of being lost fore er. "ilitant groups are ra$ing mosques and churches, smashing artifacts, bulldozing archaeological sites and illegall! trafficking antiquities at a rate rarel! seen in histor!. Iraqi cultural heritage is suffering grie ous and in man! cases irre ersible harm. To pre ent this from happening, we collect and share information, research and expert knowledge, work to raise public awareness and both de elop and execute strategies to protect heritage sites and other cultural propert! through international cooperation, advocac! and technical assistance. R&SHID International e.). Postfach ++, Institute for &ncient Near -astern &rcheology Ludwig-Maximilians/Uni ersit! of "unich 0eschwister-Scholl/*lat$ + (/,1234 "unich 0erman! https566www.rashid-international.org [email protected] Copyright This document is distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution .! International license. 8ou are free to copy and redistribute the material in an! medium or format, remix, transform, and build upon the material for an! purpose, e en commerciall!. R&SHI( International e.). cannot re oke these freedoms as long as !ou follow the license terms. -

ﻓﺎﻟﻜﻌﺒﺔ ﻗﺒةل ﻷﻫﻞ اﻟﻤﺴﺠﺪ واﳌﺴﺠﺪ ﻗﺒةل ﻷﻫﻞ اﻟﺤﺮم واﻟﺤﺮم ﻗﺒةل ﻷﻫﻞ اﻵﻓﺎق the Ka�Ba Is the Qibla for People in the Sacred Mosque

THE EARLIEST KNOWN SCHEMES OF ISLAMIC SACRED GEOGRAPHY Mónica Herrera-Casais and Petra G. Schmidl1 ﻓﺎﻟﻜﻌﺒﺔ ﻗﺒةل ﻷﻫﻞ اﻟﻤﺴﺠﺪ واﳌﺴﺠﺪ ﻗﺒةل ﻷﻫﻞ اﻟﺤﺮم واﻟﺤﺮم ﻗﺒةل ﻷﻫﻞ اﻵﻓﺎق The Kaba is the qibla for people in the Sacred Mosque. The Sacred Mosque is the qibla for people in the sacred area around it. The sacred area is the qibla for people in all regions of the world. Ibn Raīq (Yemen, eleventh century)2 1. Introduction Following injunctions in the Qurān and much discussed in the sunna, the qibla, or sacred direction of Islam, is highly significant in daily Muslim life.3 Not only the five daily ritual prayers have to be per- formed towards the Kaba in Mecca, but also other religious duties such as the recitation of the Qurān, announcing the call to prayer, ritual slaughter of animals, and the burial of the dead. Islamic sacred geography is the notion of the world being centred on the Kaba, and those who followed it proposed facing the qibla by means of simple 1 This paper arose out of a seminar on Arabic scientific manuscripts at the Insti- tute for the History of Science at Frankfurt University. We thank David King for his patience, encouragement and critical suggestions. We are also grateful to Doris Nicholson at the Bodleian Library in Oxford, and Hars Kurio at the Staatsbibliothek Preussischer Kulturbesitz in Berlin for sending free copies of manuscript folios. The authors are responsible for all inaccuracies and mistakes. [Abbreviations: KHU = Ibn Khurradādhbih; MUQ = al-Muqaddasī]. 2 In his treatise on folk astronomy studied by P.G. -

A Philosophical Hermeneutic Study of the Interview Between Minister Louis Farrakhan and Imam W

Journal of Applied Hermeneutics January 9, 2018 The Author(s) 2018 A Philosophical Hermeneutic Study of the Interview between Minister Louis Farrakhan and Imam W. Deen Mohammed: Toward a Fusion of Horizons E. Anthony Muhammad Abstract The philosophical hermeneutics of Hans-Georg Gadamer has broadened the scope and manner of hermeneutic inquiry. By focusing on aspects of Gadamer’s hermeneutics such as dialogue, the hermeneutic circle, play, openness, and the fusion of horizons, this study sought to apply Gadamer’s ideas to an historic interview that took place between two notable Islamic leaders, Minister Louis Farrakhan and Imam Warith Deen Mohammed. By analyzing the dialogue of the interview and identifying the relevant Gadamerian concepts at play within the exchanges, it was determined that a fusion of horizons did in fact occur. By applying philosophical hermeneutics to a real world dialogic encounter with participants who harbored deep-seated, divergent views, the current study accentuates the use of philosophical hermeneutics as an analytic framework. This study also highlights the utility of using philosophical hermeneutics in inter and intra-faith dialogue specifically, and in the quest for understanding in general. Keywords Hans-Georg Gadamer, philosophical hermeneutics, fusion of horizons, interfaith dialogue, Nation of Islam While early attempts to establish Islam in America were made by individuals such as Mohammed Alexander Russell Webb and the Ahmadiyyas from India, the rise of Islam in America, in large numbers, can be traced to two early movements centered in Black, inner city Corresponding Author: E Anthony Muhammad, MS Doctoral Student, University of Georgia Email: [email protected] 2 Muhammad Journal of Applied Hermeneutics 2018 Article 2 enclaves (Berg, 2009). -

Grade 5 Girls Review Seerah Mercy to Mankind Chapters 17-22 &27 1

Grade 5 Girls Review Seerah Mercy to Mankind Chapters 17-22 &27 1. Prophet Muhammad S was offered different things to stop teaching Islam including? 2. Where the poor Muslims persecuted by the Quraish? 3. Who is a kafir? What does the word mean? 4. Where is Ethiopia? 5. Why did some muslims go to Ethiopia? 6. How many went? 7. Why did the Quraish follow the Muslims to Ethiopia? 8. Which Sahabah spoke to the king of Ethiopia and convinced him to allow the Muslims to stay? 9. What is the UNHCR? 10. What does Al-Habashi mean? 11. Who is Bilal ibn Rabah Al-Habashi R? 12. What did Bilal R say when he was being tortured under the hot Arabian sand? 13. Who were the first to Shahid of Islam? 14. Who was Umm Jamil? 15. Why did people torture Rasool S? 16. How did Rasool S respond to the terrible treatment people gave him? 17. How can you respond to the ill treatment of people? 18. What can we learn from Rasool S’s patience? 19. Who was Hamza R? 20. How did Hamza R respond to Rasool S getting hurt by Abu Jahl? 21. How can we respond when we see someone being hurt by another? 22. The day Umar R became Muslim what was he setting out to do? 23. What are something we can learn about this- when we plan on doing something but another thing happens entirely? 24. What prompted Umar R to pick up the Quran and read it? 25. How can a Muslim who is angry calm down according to Rasool S’s teachings? 26.