Visconti and Visual Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language Learning Through TV: the RAI Offer Between Past and Present

Firenze University Press https://oajournals.fupress.net/index.php/bsfm-qulso Language learning through TV: the RAI off er between past and present Citation: D. Cappelli (2020) Language learning through TV: Deborah Cappelli The RAI offer between past and present. Qulso 6: pp. Università di Firenze (<deborah.cappelli@unifi .it>) 281-304. doi: http://dx.doi.org/ 10.13128/QULSO-2421-7220- 9703 Abstract: Copyright: © 2020 D. Cap- pelli. This is an open access, In the past, RAI played a fundamental role for linguistic unifi cation in Italy peer-reviewed article pub- when dialects were still the only means by which Italians were able to express lished by Firenze University themselves. In fact, the advent of TV has contributed to the spread of Italian Press (https://oaj.fupress.net/ by becoming a real language school. However, over time due to a strong mar- index.php/bsfm-qulso) and dis- keting of the off er, its commitment to education has gradually diminished tributed under the terms of the to leave more space for information and entertainment programs. Due to Creative Commons Attribution the serious emergency that hit the whole world, with the schools closed, it - Non Commercial - No deriva- became necessary for RAI to support teachers. TV brings students into con- tives 4.0 International License, tact with various communication contexts; provides them with many inputs, which permits use, distribution both linguistic and cultural, which can increase their motivation, their active and reproduction in any medi- participation in teaching practice and their knowledge. Language learning TV um, provided the original work courses can have several functions and advantages, even if originally aimed at a is properly cited as specifi ed by the author or licensor, that is not general audience, they can be integrated into school and academic teaching and used for commercial purposes become part of the program. -

March/April Staff Picks

March / April 2019 Restoration Tuesdays Canadian & International Features LEVEL 16 special Events 5TH ANNUAL ALLIANCE FRANÇAISE FRENCH FILM FESTIVAL www.winnipegcinematheque.com March 2019 TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 1 2 3 Black Lodge: Secret Cinema Anthropocene: Anthropocene: with Damien Ferland / 7 pm The Human Epoch / The Human Epoch / 5 pm Anthropocene: 3 pm & 7:15 pm Bodied / 7 pm The Human Epoch / 7 pm Bodied / 5 pm & 9 pm Bodied / 9 pm 5 6 7 8 9 10 Restoration Tuesdays: McDonald at the Movies: French Film Festival: French Film Festival: Anthropocene: French Film Festival: The Hitch-Hiker / 7 pm Some Like It Hot / 7 pm Amanda / 7 pm (Being) Women in Canada / 7 pm The Human Epoch / 3 pm Mr. Klein / 2:30 pm Detour / 8:30 pm Bodied / 9:30 pm Sink or Swim / 9 pm In Safe Hands / 9 pm French Film Festival: 16 levers de soleil / 5 pm A Summer’s Tale / 5 pm Le samouraï / 7 pm Non-Fiction / 7 pm Keep an Eye Out / 9 pm 12 13 14 15 16 17 Restoration Tuesdays: Under a Cold War Sky / 7 pm WNDX: Shakedown / 7 pm am-fm: am-fm: am-fm: Detour / 7 pm Anthropocene: Benjamin Bartlett / 7 pm Panel: Gender Roles Algéria, De Gaulle and The Hitch-Hiker / 9 pm The Human Epoch / 9 pm I Still Hide to Smoke / 9 pm in Film / 1 pm the bomb / 2 pm Malaria Business / 3 pm To the Ghost of the Father / 4 pm N.G.O. (Nothing Going On) / 5 pm Keteke / 6 pm Zizou / 7:15 pm A Day for Women / 9:30 pm 19 20 21 22 23 24 Restoration Tuesdays: Best of Gimli: Best of Gimli: Decasia / 7 pm Decasia / 3 pm Falls Around Her / 3 pm & 7 pm The Hitch-Hiker / -

Former Political Prisoners and Exiles in the Roman Revolution of 1848

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1989 Between Two Amnesties: Former Political Prisoners and Exiles in the Roman Revolution of 1848 Leopold G. Glueckert Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Glueckert, Leopold G., "Between Two Amnesties: Former Political Prisoners and Exiles in the Roman Revolution of 1848" (1989). Dissertations. 2639. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/2639 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1989 Leopold G. Glueckert BETWEEN TWO AMNESTIES: FORMER POLITICAL PRISONERS AND EXILES IN THE ROMAN REVOLUTION OF 1848 by Leopold G. Glueckert, O.Carm. A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 1989 Leopold G. Glueckert 1989 © All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As with any paper which has been under way for so long, many people have shared in this work and deserve thanks. Above all, I would like to thank my director, Dr. Anthony Cardoza, and the members of my committee, Dr. Walter Gray and Fr. Richard Costigan. Their patience and encourage ment have been every bit as important to me as their good advice and professionalism. -

THE LEOPARD/IL GATTOPARDO (1963) Original 205Min, UK 195, US 165, Restored ?

6 December 2005, XI:15 LUCHINO VISCONTI (Count Don Lucino Visconti di Modrone, 2 November 1906, Milan—17 March 1976, Rome) wrote or co-wrote and directed all or part of 19 other films, the best known of which are L’Innocente 1976, Morte a Venezia/Death in Venice 1971, La Caduta degli dei/The Damned 1969, Lo Straniero/The Stranger 1967, Rocco e i suoi fratelli/Rocco and His Brothers 1960, Le Notti bianche/White Nights 1957, and Ossessione 1942. SUSO CECCHI D'AMICO (Giovanna Cecchi, 21 July 1914, Rome) daughter of screenwriter Emilio Cecchi, wrote or co-wrote nearly 90 films, the first of which was the classic Roma citt libera/Rome, Open City 1946. Some of the others: Panni sporchi/Dirty Linen 1999, Il Male oscuro/Obscure Illness 1990, L’Innocente 1976, Brother Sun, Sister Moon 1973, Lo Straniero/The Stranger 1967, Spara forte, pi forte, non capisco/Shoot Louder, I Don’t Understand 1966, I Soliti ignoti/Big Deal on Madonna Street 1958, Le Notti bianche/White Nights 1957, and Ladri di biciclette/The Bicycle Thieves 1948. PASQUALE FESTA CAMPANILE (28 July 1927, Melfi, Basilicata, Italy—25 February 1986, Rome) directed 45 films which we mention here primarily because the American and British release titles are so cockamamie, i.e., How to Lose a Wife and Find a Lover 1978, Sex Machine 1975, When Women Played Ding Dong 1971, When Women Lost Their Tails 1971, When Women Had Tails 1970, Where Are You Going All Naked? 1969, The Chastity Belt/On My Way to the Crusades, I Met a Girl Who...1969, and Drop Dead My Love 1966. -

Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND Index 2016_4.indd 1 14/12/2016 17:41 SUBJECT INDEX SUBJECT INDEX After the Storm (2016) 7:25 (magazine) 9:102 7:43; 10:47; 11:41 Orlando 6:112 effect on technological Film review titles are also Agace, Mel 1:15 American Film Institute (AFI) 3:53 Apologies 2:54 Ran 4:7; 6:94-5; 9:111 changes 8:38-43 included and are indicated by age and cinema American Friend, The 8:12 Appropriate Behaviour 1:55 Jacques Rivette 3:38, 39; 4:5, failure to cater for and represent (r) after the reference; growth in older viewers and American Gangster 11:31, 32 Aquarius (2016) 6:7; 7:18, Céline and Julie Go Boating diversity of in 2015 1:55 (b) after reference indicates their preferences 1:16 American Gigolo 4:104 20, 23; 10:13 1:103; 4:8, 56, 57; 5:52, missing older viewers, growth of and A a book review Agostini, Philippe 11:49 American Graffiti 7:53; 11:39 Arabian Nights triptych (2015) films of 1970s 3:94-5, Paris their preferences 1:16 Aguilar, Claire 2:16; 7:7 American Honey 6:7; 7:5, 18; 1:46, 49, 53, 54, 57; 3:5: nous appartient 4:56-7 viewing films in isolation, A Aguirre, Wrath of God 3:9 10:13, 23; 11:66(r) 5:70(r), 71(r); 6:58(r) Eric Rohmer 3:38, 39, 40, pleasure of 4:12; 6:111 Aaaaaaaah! 1:49, 53, 111 Agutter, Jenny 3:7 background -

California State University, Sacramento Department of World Literatures and Languages Italian 104 a INTRODUCTION to ITALIAN CINEMA I GE Area C1 SPRING 2017

1 California State University, Sacramento Department of World Literatures and Languages Italian 104 A INTRODUCTION TO ITALIAN CINEMA I GE Area C1 SPRING 2017 Course Hours: Wednesdays 5:30-8:20 Course Location: Mariposa 2005 Course Instructor: Professor Barbara Carle Office Location: Mariposa Hall 2057 Office Hours: W 2:30-3:30, TR 5:20-6:20 and by appointment CATALOG DESCRIPTION ITAL 104A. Introduction to Italian Cinema I. Italian Cinema from the 1940's to its Golden Period in the 1960's through the 1970's. Films will be viewed in their cultural, aesthetic and/or historical context. Readings and guiding questionnaires will help students develop appropriate viewing skills. Films will be shown in Italian with English subtitles. Graded: Graded Student. Units: 3.0 COURSE GOALS and METHODS: To develop a critical knowledge of Italian film history and film techniques and an aesthetic appreciation for cinema, attain more than a mere acquaintance or a broad understanding of specific artistic (cinematographic) forms, genres, and cultural sources, that is, to learn about Italian civilization (politics, art, theatre and customs) through cinema. Guiding questionnaires will also be distributed on a regular basis to help students achieve these goals. All questionnaires will be graded. Weekly discussions will help students appreciate connections between cinema and art and literary movements, between Italian cinema and American film, as well as to deal with questionnaires. You are required to view the films in the best possible conditions, i.e. on a large screen in class. Viewing may be enjoyable but is not meant to be exclusively entertaining. -

Titoli Delle Video Cassette Di Proprieta' Della Civica Biblioteca

ELENCO VIDEO CASSETTE - DOCUMENTARI TITOLO LUOGO E CASA DI DISTRIBUZIONE ANNO DURATANUM. INV. (L') ACROBATA DEI BOSCHI Milano, Airone Video 1989 60 minuti 2 AI COMANDI DEI GRANDI AEREI STORICI Parma, Delta Editrice s.d. 872 ALLA SCOPERTA DELLA NUOVA MINI Milano, Domus s.d. 15 minuti 164 (L') ALTRA FACCIA DEI DELFINI Roma, National Geographich 1999 60 minuti 56 (L') ALTRA FACCIA DEL SOLE Roma, National Geographich 2000 60 minuti 278 AMSTERDAM - Città del mondo Novara, De Agostini 1994 40 minuti 117 (GLI) ANIMALI DELLA FATTORIA -Animali in primo piano Novara, De Agostini 1995 60 minuti 16 ANZACS. GLI EORI DELL'ALTRO MONDO Londra, BBC 2003 689 ATENE METEORE - Città del mondo Novara, De Agostini 1995 40 minuti 118 AUSTRALIA LA SECONDA CREAZIONE Milano, Airone Video 1990 60 minuti 3 (L') AVANA -Città del mondo Novara, De Agostini 1995 40 minuti 119 (LA) BALENA REGINA DEGLI OCEANI - Animali in primo piano Novara, De Agostini 1995 60 minuti 17 (IL) BANCHETTO DEI COCCODRILLI Roma, National Geographich 1995 60 minuti 57 BANGKOK -Città del mondo Novara, De Agostini 1994 40 minuti 120 BARCELLONA -Città del mondo Novara, De Agostini 1994 40 minuti 121 (LA) BELLA E LE BESTIE. VITA DI UN LEOPARDO Roma, National Geographich 1995 60 minuti 353 BERNA - Città del mondo Novara, De Agostini 1994 40 minuti 122 (LA) BIBLIOTECA TRA SPAZIO E PROGETTO Milano, Regione Lombardia 1996 12 minuti 15 BRESCIA. IL SAPORE DI UNA CITTA'. Milano, Regione Lombardia s.d. 349 BRUXELLES BRUGES - Città del mondo Novara, De Agostini 1995 40 minuti 123 BUDAPEST -Città del mondo Novara, De Agostini 1994 40 minuti 124 BUDDISMO - Le grandi religioni Milano, San Paolo 1997 30 minuti 928 BUFALI E BISONTI - Animali in primo piano Novara, De Agostini 1995 60 minuti 18 LA) BUONA NOVELLA DI FABRIZIO DE ANDRE' Torino, Einaudi Video s.d. -

Unlocking Australia's Language Potential. Profiles of 9 Key Languages in Australia

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 384 206 FL 022 494 AUTHOR Di Biase, Bruno; And Others TITLE Unlocking Australia's Language Potential. Profiles of 9 Key Languages in Australia. Volume 6: Italian. INSTITUTION Australian National Languages and Literacy Inst., Deakin. REPORT NO ISBN-1-875578-13-7 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 276p.; For related documents, see FL 022 493-497 and ED 365 111-114. AVAILABLE FROMNLLIA, 9th Level, 300 Flinders St., Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia. PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070) Tests/Evaluation Instruments (160) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Education; Continuing Education; Cultural Awareness; Cultural Education; Educational History; *Educational Needs; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Government Role; Higher Education; International Trade; *Italian; *Language Maintenance; *Language Role; Language Usage; Regional Characteristics; Second Language Learning; *Second Languages; Teacher Education; Technological Advancement; Tourism IDENTIFIERS *Australia; *Italy ABSTRACT The status of the Italian language in Australia, particularly in the educational system at all levels, in Australian society in general, and in trade, technology, and tourism is discussed in this report. It begins with a description of the teaching of Italian in elementary, secondary, higher, adult/continuing, and teacher education. Trends are traced from the 1950s through the 1980s, looking at political and religious factors in its evolution, formation of national policy, curriculum and assessment approaches, professional issues in teacher education, and research on learning motivations and attitudes toward Italian. Development of public policies and initiatives is chronicled from the 1970s, with specific reports, events, and programs highlighted. Teaching oF Italian in various areas of Australia is also surveyed. A discussion of the role of Italian in Australian society looks at the impact of migration, language shift and maintenance, demographics of the Italian-speaking community, and cultural and language resources within that community. -

Annual Corporate Governance Report for Listed Companies

ANNUAL CORPORATE GOVERNANCE REPORT FOR LISTED COMPANIES ISSUER IDENTIFICATION YEAR-END DATE 31/12/2018 TAX IDENTIFICATION NUMBER: A-78839271 Company name: ATRESMEDIA CORPORACION DE MEDIOS DE COMUNICACION, S.A. Registered office: AVENIDA ISLA GRACIOSA, 13 (S. SEBASTIAN DE LOS REYES) MADRID 1 / 93 ANNUAL CORPORATE GOVERNANCE REPORT FOR LISTED COMPANIES A. CAPITAL STRUCTURE A.1.Complete the table below with details of the share capital of the company: Date of last Number of shares Number of voting Share capital (€) change rights 25/04/2012 169,299,600.00 225,732,800 225,732,800 Please state whether there are different classes of shares with different associated rights: [ ] Yes [ √ ] No A.2. Please provide details of the company’s significant direct and indirect shareholders at year end, excluding any directors: Name or % of shares carrying voting % of voting rights through company rights financial instruments % of total voting name of Direct Indirect Direct Indirect rights shareholder GRUPO PLANETA 0.00 41.70 0.00 0.00 41.70 DE AGOSTINI, S.L. RTL GROUP, S.A. 0.00 18.65 0.00 0.00 18.65 IMAGINA MEDIA AUDIOVISUAL, 4.23 0.00 0.00 0.00 4.23 S.A.U. Breakdown of the indirect holding: Name of direct Name of indirect % of shares % of voting rights % of total voting shareholder shareholder carrying through financial rights voting rights instruments UFA FILM UND RTL GROUP, S.A. 18.65 0.00 18.65 FERNSEH, GMBH GRUPO PLANETA GRUPO PASA 41.70 0.00 41.70 DE AGOSTINI, S.L. CARTERA, S.A.U. -

War and Peace in Europe from Napoleon to the Kaiser: the Wars of German Unification, 1864- 1871 Transcript

War and Peace in Europe from Napoleon to the Kaiser: The Wars of German Unification, 1864- 1871 Transcript Date: Thursday, 4 February 2010 - 12:00AM Location: Museum of London The Wars of German Unification 1864-1871 Professor Richard J Evans 4/2/2010 Of all the war that took place in the nineteenth century, perhaps the most effective in gaining their objectives, the most carefully delimited in scope, the best planned, and the most clinically and efficiently executed, were the three wars fought by Prussia in the 1860s, against Denmark, against Austria, and against France. Not all of them went entirely to plan, as we shall see, particularly not the last of the three, but all of them were in nearly all respects classic examples of limited war, of the Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz's dictum that war is politics continued by other means. After the muddle, incompetence and indecisiveness of the Crimean War, the wars of the 1860s seemed to belong to another world. How and why were these three wars fought? I argued in my earlier lectures that the 1848 Revolutions, though they failed in many if not most respects, undermined the international order established at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, opening up the international scene to new initiatives and instabilities. The joker in the pack here was the French Emperor Napoleon III, whose search for foreign glory and foreign victories as a way of legitimating his dictatorial rule at home led him into one military adventure after another, some successful, others less so. It was among other things French military intervention that secured victory for Piedmont-Sardinia over the Austrians in 1859, though the drive for Italian unity then became unstoppable, thanks not least to the activities of the revolutionary nationalist Giuseppe Garibaldi, much to Napoleon III's discomfiture. -

Confirmed 2021 Buyers / Commissioners

As of April 13th Doc & Drama Kids Non‐Scripted COUNTRY COMPANY NAME JOB TITLE Factual Scripted formats content formats ALBANIA TVKLAN SH.A Head of Programming & Acq. X ARGENTINA AMERICA VIDEO FILMS SA CEO XX ARGENTINA AMERICA VIDEO FILMS SA Acquisition ARGENTINA QUBIT TV Acquisition & Content Manager ARGENTINA AMERICA VIDEO FILMS SA Advisor X SPECIAL BROADCASTING SERVICE AUSTRALIA International Content Consultant X CORPORATION Director of Television and Video‐on‐ AUSTRALIA ABC COMMERCIAL XX Demand SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS AUSTRALIA Head of Business Development XXXX AUSTRALIA SPECIAL BROADCASTING SERVICE AUSTRALIA Acquisitions Manager (Unscripted) X CORPORATION SPECIAL BROADCASTING SERVICE Head of Network Programming, TV & AUSTRALIA X CORPORATION Online Content AUSTRALIA ABC COMMERCIAL Senior Acquisitions Manager Fiction X AUSTRALIA MADMAN ENTERTAINMENT Film Label Manager XX AUSTRIA ORF ENTERPRISE GMBH & CO KG content buyer for Dok1 X Program Development & Quality AUSTRIA ORF ENTERPRISE GMBH & CO KG XX Management AUSTRIA A1 TELEKOM AUSTRIA GROUP Media & Content X AUSTRIA RED BULL ORIGINALS Executive Producer X AUSTRIA ORF ENTERPRISE GMBH & CO KG Com. Editor Head of Documentaries / Arts & AUSTRIA OSTERREICHISCHER RUNDFUNK X Culture RTBF RADIO TELEVISION BELGE BELGIUM Head of Documentary Department X COMMUNAUTE FRANCAISE BELGIUM BE TV deputy Head of Programs XX Product & Solutions Team Manager BELGIUM PROXIMUS X Content Acquisition RTBF RADIO TELEVISION BELGE BELGIUM Content Acquisition Officer X COMMUNAUTE FRANCAISE BELGIUM VIEWCOM Managing -

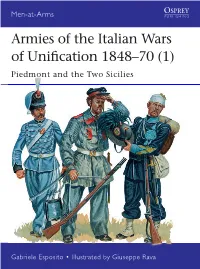

Armies of the Italian Wars of Unification 1848–70 (1)

Men-at-Arms Armies of the Italian Wars of Uni cation 1848–70 (1) Piedmont and the Two Sicilies Gabriele Esposito • Illustrated by Giuseppe Rava GABRIELE ESPOSITO is a researcher into military CONTENTS history, specializing in uniformology. His interests range from the ancient HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 3 Sumerians to modern post- colonial con icts, but his main eld of research is the military CHRONOLOGY 6 history of Latin America, • First War of Unification, 1848-49 especially in the 19th century. He has had books published by Osprey Publishing, Helion THE PIEDMONTESE ARMY, 1848–61 7 & Company, Winged Hussar • Character Publishing and Partizan Press, • Organization: Guard and line infantry – Bersaglieri – Cavalry – and he is a regular contributor Artillery – Engineers and Train – Royal Household companies – to specialist magazines such as Ancient Warfare, Medieval Cacciatori Franchi – Carabinieri – National Guard – Naval infantry Warfare, Classic Arms & • Weapons: infantry – cavalry – artillery – engineers and train – Militaria, Guerres et Histoire, Carabinieri History of War and Focus Storia. THE ITALIAN ARMY, 1861–70 17 GIUSEPPE RAVA was born in • Integration and resistance – ‘the Brigandage’ Faenza in 1963, and took an • Organization: Line infantry – Hungarian Auxiliary Legion – interest in all things military Naval infantry – National Guard from an early age. Entirely • Weapons self-taught, Giuseppe has established himself as a leading military history artist, THE ARMY OF THE KINGDOM OF and is inspired by the works THE TWO SICILIES, 1848–61 20 of the great military artists, • Character such as Detaille, Meissonier, Rochling, Lady Butler, • Organization: Guard infantry – Guard cavalry – Line infantry – Ottenfeld and Angus McBride. Foreign infantry – Light infantry – Line cavalry – Artillery and He lives and works in Italy.