A Macroeconometric Model for Slovenia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slovenia Have Been Remarkable

Mrak/Rojec/Silva-Jáur lovenia’s achievements over the past several years Slovenia have been remarkable. Thirteen years after Public Disclosure Authorized independence from the former Socialist Federative egui Republic of Yugoslavia, the country is among the most advanced of all the transition economies in Central and Eastern Europe and a leading candidate for accession to the European Union Sin May 2004. Remarkably, however, very little has been published Slovenia documenting this historic transition. Fr om Y In the only book of its kind, the contributors—many of them the architects of Slovenia’s current transformation—analyze the country’s three-fold ugoslavia to the Eur transition from a socialist to a market economy, from a regionally based to a national economy, and from being a part of the Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia to being an independent state and a member of the European Union (EU). With chapters from Slovenia’s president, a former vice prime minister, Public Disclosure Authorized the current and previous ministers of finance, the minister of European affairs, the current and former governors of the Bank of Slovenia, as well as from leading development scholars in Slovenia and abroad, this unique opean Union collection synthesizes Slovenia’s recent socioeconomic and political history and assesses the challenges ahead. Contributors discuss the Slovenian style of socioeconomic transformation, analyze Slovenia’s quest for EU membership, and place Slovenia’s transition within the context of the broader transition process taking place in Central and Eastern Europe. Of interest to development practitioners and to students and scholars of the region, Slovenia: From Yugoslavia to the European Union is a From Yugoslavia comprehensive and illuminating study of one country’s path to political and economic independence. -

Small Economies in the Euro Area

CONTENTS EDITORIAL Mitja Gaspari: Jumping the Last Hurdle Towards the Final Stage of Convergence 1 MACROECONOMIC FRAMEWORK OF SMALL OPEN ECONOMY Willem H. Buiter and Anne C. Sibert: When Should the New Central European Members Join the Eurozone? 5 George Kopits: Policy Scenarios for Adopting the Euro 12 Dejan Krušec: Common Monetary Policy and Small Open Economies 17 Lars Calmfors: The Revised Stability and Growth Pact – A Critical Assessment 22 Fabio Mucci and Debora Revoltella: Banking Systems in the New EU Members and Acceding Countries 27 Mathilde Maurel: The Political Business Cycles in the EU Enlarged 38 FINANCIAL MARKETS AND FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS IN EMU Kevin R. James: Small Countries, Big Markets: Achieving Financial Stability in Small Sophisticated Economies 43 Garry J. Schinasi and Pedro Gustavo Teixeira: Financial Crisis Management in the European Single Financial Market 47 Franjo Štiblar: Consolidations and Diversifications in Financial Sector 56 Fabrizio Coricelli: Financial Deepening and Financial Integration of New EU Countries 70 THE CASE OF SLOVENIA Ivan Ribnikar: Slovenian »Transition« and Monetary Policy 75 Igor Masten: Expected Stabilization Effects of Euro Adoption on Slovenian Economy 83 Velimir Bole: Fiscal Policy in Slovenia after Entering Euro – New Goals and Soundness? 87 Božo Jašovič and Borut Repanšek: Application of the Balance Sheet Approach to Slovenia 95 STATISTICAL APPENDIX Matjaž Noč: Selected Macroeconomic and Financial Indicators 105 EDITORIAL Jumping the Last Hurdle Towards the Final Stage of Convergence Mitja Gaspari * n 1 January 2007, Slovenia will join the 12 current members of the euro area and adopt the single European currency. This is a historic moment for Slovenia and for euro area enlargement. -

Demand-Side Or Supply-Side Stabilisation Policies in a Small Euro

Empirica https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-021-09503-y ORIGINAL PAPER Demand‑side or supply‑side stabilisation policies in a small euro area economy: a case study for Slovenia Reinhard Neck1 · Klaus Weyerstrass2 · Dmitri Blueschke1 · Miroslav Verbič3 Accepted: 25 February 2021 © The Author(s) 2021 Abstract In this paper we analyse the efectiveness of demand- and supply-side fscal poli- cies in the small open economy of Slovenia. Simulating the SLOPOL10 model, an econometric model of the Slovenian economy, we analyse the efectiveness of vari- ous categories of public spending and taxes during the period 2020 to 2030, assum- ing that no crisis occurs. Our simulations show that those public spending measures that entail both demand- and supply-side efects are more efective at stimulating real GDP and increasing employment than pure demand-side measures. This is due to the fact that supply-side measures also increase potential and not only actual GDP. Measures which foster research and development and those which improve the education level of the labour force are particularly efective in this respect. Employ- ment can also be stimulated efectively by cutting the income tax rate and the social security contribution rate, i.e. by reducing the tax wedge on labour income, which positively afects Slovenia’s international competitiveness. Successful stabilisation policies should thus contain a supply-side component in addition to a demand-side component. We also provide a frst simulation of potential efects of the Covid-19 crisis on the Slovenian economy, which is modelled as a combined demand and sup- ply shock. Keywords Macroeconomics · Stabilisation policy · Fiscal policy · Tax policy · Public expenditure · Demand management · Supply-side policies · Slovenia · Public debt JEL Codes E62 · E17 · E37 Responsible Editor: Harald Oberhofer. -

European Union

EUROPEAN UNION Brussels, 27 June 2004 COMMUNIQUE At the request of the Slovenian authorities, the ministers of the euro area Member States of the European Union, the President of the European Central Bank and the ministers and the central bank governors of Denmark and Slovenia have decided, by mutual agreement, following a common procedure involving the European Commission and after consultation of the Economic and Financial Committee, to include the Slovenian tolar in the Exchange Rate Mechanism II (ERM II). The central rate of the Slovenian tolar is set at 1 euro = 239.640 tolar. The standard fluctuation band of plus or minus 15 percent will be observed around the central rate of the tolar. The agreement on participation of the tolar in ERM II is based on a firm commitment by the Slovenian authorities to continue to take the necessary measures to lower inflation in a sustainable way: these include most notably measures aimed at further liberalising administered prices and advancing further with de-indexation, in particular of the wage and certain social transfer setting mechanisms. Continued vigilance will be needed so that domestic cost developments, in particular wages, are in line with productivity growth. The authorities, together with the responsible EU bodies, will closely monitor macroeconomic developments. Fiscal policy will have to play a central role in controlling demand-induced inflationary pressures and financial supervision will assist in containing domestic credit growth. Structural reforms aimed at further enhancing the economy’s flexibility and adaptability will be implemented in a timely fashion so as to strengthen domestic adjustment mechanisms and to maintain the overall competitiveness of the economy. -

Central Bank Sterilization Policy: the Experiences of Slovenia and Lessons for Countries in Southeastern Europe1

√ Workshops Proceedings of OeNB Workshops Any Lessons for Southeastern Europe? Lessons for Any Emerging Markets: Any Lessons for Southeastern Europe? Emerging Markets: Emerging March 5 and 6, 2007 12 No. Workshops N0. N0. Workshops 12 Stability and Security. Central Bank Sterilization Policy: The Experiences of Slovenia and Lessons for 1 Countries in Southeastern Europe Darko Bohnec Banka Slovenije Marko Košak University of Ljubljana 1. Introduction It is well known that countries in the Southeastern European (SEE) region have experienced a substantial and gradually intensified inflow of foreign capital during the entire period of economic transition (Markievicz, 2006). Central banks in those countries had to adapt their monetary policy operations and exchange rate regimes to the changing conditions. Especially in those countries that responded by implementing a managed floating exchange rate regime, central banks had to find viable solutions in order to support the “consistency triangle” policy framework (Bofinger and Wollmershaeuser, 2001). Advocates of the “consistency triangle” policy framework claim that simultaneous determination of the optimum interest rate level and the optimum exchange rate path is possible. Effective sterilization procedures need to be activated by the central bank in order for the policy framework to be operational. The experiences of some developing countries in the 1990s confirm the viability of sterilization as a key element of the central bank’s monetary policy in circumstances of intensified inflow of foreign capital (Lee, 1996). However, certain limitations to this kind of strategy exist, which in most cases central banks need to address properly by developing alternative procedures and instruments instead of classical open-market operations. -

WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates

The WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates The WM/Refinitiv Closing Exchange Rates are available on Eikon via monitor pages or RICs. To access the index page, type WMRSPOT01 and <Return> For access to the RICs, please use the following generic codes :- USDxxxFIXz=WM Use M for mid rate or omit for bid / ask rates Use USD, EUR, GBP or CHF xxx can be any of the following currencies :- Albania Lek ALL Austrian Schilling ATS Belarus Ruble BYN Belgian Franc BEF Bosnia Herzegovina Mark BAM Bulgarian Lev BGN Croatian Kuna HRK Cyprus Pound CYP Czech Koruna CZK Danish Krone DKK Estonian Kroon EEK Ecu XEU Euro EUR Finnish Markka FIM French Franc FRF Deutsche Mark DEM Greek Drachma GRD Hungarian Forint HUF Iceland Krona ISK Irish Punt IEP Italian Lira ITL Latvian Lat LVL Lithuanian Litas LTL Luxembourg Franc LUF Macedonia Denar MKD Maltese Lira MTL Moldova Leu MDL Dutch Guilder NLG Norwegian Krone NOK Polish Zloty PLN Portugese Escudo PTE Romanian Leu RON Russian Rouble RUB Slovakian Koruna SKK Slovenian Tolar SIT Spanish Peseta ESP Sterling GBP Swedish Krona SEK Swiss Franc CHF New Turkish Lira TRY Ukraine Hryvnia UAH Serbian Dinar RSD Special Drawing Rights XDR Algerian Dinar DZD Angola Kwanza AOA Bahrain Dinar BHD Botswana Pula BWP Burundi Franc BIF Central African Franc XAF Comoros Franc KMF Congo Democratic Rep. Franc CDF Cote D’Ivorie Franc XOF Egyptian Pound EGP Ethiopia Birr ETB Gambian Dalasi GMD Ghana Cedi GHS Guinea Franc GNF Israeli Shekel ILS Jordanian Dinar JOD Kenyan Schilling KES Kuwaiti Dinar KWD Lebanese Pound LBP Lesotho Loti LSL Malagasy -

SLOVENIA Tatjana Rakar Zinka Kolarič

SOCIAL ENTERPRISES AND THEIR ECOSYSTEMS IN EUROPE Country report SLOVENIA Tatjana Rakar Zinka Kolarič Social Europe This report is part of the study “Social enterprises and their ecosystems in Europe” and it provides an overview of the social enterprise landscape in Slovenia based on available information as of March 2019. It describes the roots and drivers of social enterprises in the country as well as their conceptual, fiscal and legal framework. It includes an estimate of the number of organisations and outlines the ecosystem as well as some perspectives for the future of social enterprises in the country. This publication is an outcome of an assignment financed entirely by the European Union Programme for Employment and Social Innovation "EaSI" (2014-2020). For further information please consult: http://ec.europa.eu/social/easi Manuscript completed in August 2019 1st edition Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use that might be made of the following information. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2019 © European Union, 2019 Reuse is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. The reuse policy of European Commission documents is regulated by Decision 2011/833/EU (OJ L 330, 14.12.2011, p. 39). For any use or reproduction of photos or other material that is not under the EU copyright, permission must be sought directly from the copyright holders. Catalogue number KE-05-18-117-EN-N ISBN 978-92-79-97925-5 | DOI 10.2767/203806 You can download our -

Global Economic Outlook, September

Unedited United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs LINK Global Economic Outlook 2018-2020 Presented at the DESA Expert Group Meeting on the World Economy (Project LINK) Co-sponsored and hosted by ECLAC, Santiago, Chile 5-7 September 2018 1 Acknowledgements This report presents the short-term prospects for the global economy in 2018-2020, including major risks and policy challenges. The report draws on the analysis of staff in the Global Economic Monitoring Branch (GEMB) of the Economic Analysis and Development Division (EAPD), United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA), and on inputs provided by the experts of Project LINK. The current report was coordinated by GEMB, with contributions from Helena Afonso, Grigor Agabekian, Dawn Holland, Matthias Kempf, Poh Lynn Ng, Ingo Pitterle, Michal Podolski, Sebastian Vergara and Yasuhisa Yamamoto. Pingfan Hong provided general guidance. This report is prepared for the UN DESA Expert Group Meeting on the World Economy (Project LINK) to be held on 5-7 September 2018 at ECLAC Headquarters in Santiago. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of the United Nations or its Member States. 2 Contents Section 1: Prospects for the world economy .............................................................................. 5 Global overview ..................................................................................................................... 5 Macroeconomic policy stance ............................................................................................. -

Slovenia Country Profile

SLOVENIA COUNTRY PROFILE UNITED NATIONS INTRODUCTION - 2002 COUNTRY PROFILES SERIES Agenda 21, adopted at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, underscored the important role that States play in the implementation of the Agenda at the national level. It recommended that States consider preparing national reports and communicating the information therein to the Commission on Sustainable Development (CSD) including, activities they undertake to implement Agenda 21, the obstacles and challenges they confront, and other environment and development issues they find relevant. As a result, in 1993 governments began preparing national reports for submission to the CSD. After two years of following this practice, the CSD decided that a summarized version of national reports submitted thus far would be useful. Subsequently, the CSD Secretariat published the first Country Profiles series in 1997 on the occasion of the five-year review of the Earth Summit (Rio + 5). The series summarized, on a country-by-country basis, all the national reports submitted between 1994 and 1996. Each Profile covered the status of all Agenda 21 chapters. The purpose of Country Profiles is to: · Help countries monitor their own progress; · Share experiences and information with others; and · Serve as institutional memory to track and record national actions undertaken to implement Agenda 21. A second series of Country Profiles is being published on the occasion of the World Summit on Sustainable Development being held in Johannesburg from August 26 to September 4, 2002. Each profile covers all 40 chapters of Agenda 21, as well as those issues that have been separately addressed by the CSD since 1997, including trade, energy, transport, sustainable tourism and in dustry. -

European Economy. Convergence Report 2004

European Economy Convergence Report 2004 – Technical annex A Commission services working paper SEC(2004)1268 PROVISIONAL LAYOUT The definitive version will be published as European Economy No 6/2004 http://europa.eu.int/comm/economy_finance/publications/european_economy/convergencereports2004_en.htm Acknowledgements This paper was prepared in the Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs under the supervision of Klaus Regling, Director-General, and Antonio J. Cabral, Deputy Director-General. The main contributors to the paper were Johan Baras, Sean Berrigan, Carsten Brzeski, Adriaan Dierx, Christine Gerstberger, Alexandr Hobza, Fabienne Ilzkovitz, Filip Keereman, Paul Kutos, Baudouin Lamine, João Nogueira Martins, Moises Orellana Pena, Lucio R. Pench, Jiri Plecity, Stéphanie Riso, Delphine Sallard, Charlotte Van Hooydonk, Johan Verhaeven and Joachim Wadefjord. Country-specific contributions were provided by Georg Busch, Juan Ramon Calaf Sole, Nathalie Darnaut, Per Eckefeldt, Luis Fau Sebastian, Barbara Kauffmann, Filip Keereman, Viktoria Kovacs, Carlos Martinez Mongay, Marek Mora, Willem Noë, Mateja Peternelj, José Luis Robledo Fraga, Agnieszka Skuratowicz, Siegfried Steinlein, Kristine Vlagsma, Helga Vogelmann and Ralph Wilkinson. Charlotte Van Hooydonk edited the paper. Statistical and technical assistance was provided by Vittorio Gargaro, Tony Tallon and André Verbanck. Contents 1. Introduction and overview.................................................................................................................1 -

Exchange Rate of the Slovenian Tolar in the Context of Slovenia's Inclusion in the Eu and in the Emu

EXCHANGE RATE OF THE SLOVENIAN TOLAR IN THE CONTEXT OF SLOVENIA'S INCLUSION IN THE EU AND IN THE EMU 9ODGLPLU /DYUDþ WORKING PAPER No. 1, 1999 EXCHANGE RATE OF THE SLOVENIAN TOLAR IN THE CONTEXT OF SLOVENIA'S INCLUSION IN THE EU AND IN THE EMU 9ODGLPLU /DYUDþ WORKING PAPER No. 1, 1999 E-mail address of the author: [email protected] Editor of the WP series: Peter Stanovnik © 1999 Inštitut za ekonomska raziskovanja This paper is also available on Internet home page: http//www.ier.si Ljubljana, January 1999 2 Introduction Creation of the European economic and monetary union (EMU) and successive introduction of the European single currency, the euro, is a historic event, which will lead to fundamental changes in the EU economies. These changes will undoubtedly have a significant impact on the economies of the Central European transition countries, candidates for a full membership in the EU, similarly as the preparations of the EU countries for the EMU and their efforts to meet the Maastricht convergence criteria have already affected the Central European economies. Policy-makers and other decision-makers at various levels (enterprises, banks, government bodies) will have to adapt to the changing environment, first by adjusting to the irrevocably fixed exchange rates among the EU currencies participating in the EMU and then by adjusting to the introduction of the euro and to the elimination of national currencies in the euro zone. This paper, however, does not concentrate on these otherwise important issues of the impact of the EMU on the Central European countries. It focuses primarily on the most direct questions related to the EMU for these countries - why, how and when Slovenia and the other Central European EU candidate countries will be ready to join the EMU. -

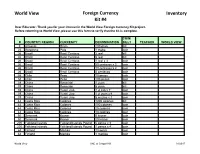

World View Foreign Currency Kit #4 Inventory

World View Foreign Currency Inventory Kit #4 Dear Educator: Thank you for your interest in the World View Foreign Currency Kit project. Before returning to World View, please use this form to verify that the kit is complete. COIN/ # COUNTRY/ REGION CURRENCY DENOMINATION BILL? TEACHER WORLD VIEW 9 Armenia Dram 200 dram bill 25 Botswana Pula 1 thebe coin 26 Brazil Real/ Centavo 2 real bill 26 Brazil Real/ Centavo 5 real bill 26 Brazil Real/ Centavo 1 real x 3 coin 26 Brazil Real/ Centavo 50 centavos x 2 coin 26 Brazil Real/ Centavo 10 centavos x 2 coin 26 Brazil Real/ Centavo 5 centavos coin 38 Chile Peso 10 pesos coin 38 Chile Peso 100 pesos coin 39 China Renminbi 1 yuan bill 39 China Renminbi 5 yuan bill 39 China Yuan/ Jiao 1 yi jiao x 7 coin 39 China Yuan/ Jiao 1 yi yuan x 6 coin 39 China Yuan/ Jiao 5 wu jiao x 2 coin 44 Costa Rica Colones 1000 colones bill 44 Costa Rica Colones 100 colones coin 44 Costa Rica Colones 25 colones coin 44 Costa Rica Colones 10 colones coin 50 Denmark Kroner 5 kroner coin 50 Denmark Kroner 20 kroner coin 200 Falkland Islands Falkland Islands Pound 5 pence x 3 coin 200 Falkland Islands Falkland Islands Pound 1 pence x 4 coin 64 Finland Markka 10 penni coin 64 Finland Markka 1 markka coin World View UNC at Chapel Hill 01/2017 World View Foreign Currency Inventory Kit #4 69 Germany Deutsche Mark 10 Deutsche mark bill 80 Hungary Forint 20 forint coin 80 Hungary Forint 100 forint coin 80 Hungary Forint 5 forint coin 92 Japan Yen 1 yen x 2 coin 92 Japan Yen 10 yen coin 92 Japan Yen 100 yen x 2 coin 92 Japan Yen