Discipleship in the Context of Judaism in Jesus' Time Part I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Jewish Yearbook

JEWISH STATISTICS 277 JEWISH STATISTICS The statistics of Jews in the world rest largely upon estimates. In Russia, Austria-Hungary, Germany, and a few other countries, official figures are obtainable. In the main, however, the num- bers given are based upon estimates repeated and added to by one statistical authority after another. For the statistics given below various authorities have been consulted, among them the " Statesman's Year Book" for 1910, the English " Jewish Year Book " for 5670-71, " The Jewish Ency- clopedia," Jildische Statistik, and the Alliance Israelite Uni- verselle reports. THE UNITED STATES ESTIMATES As the census of the United States has, in accordance with the spirit of American institutions, taken no heed of the religious convictions of American citizens, whether native-born or natural- ized, all statements concerning the number of Jews living in this country are based upon estimates. The Jewish population was estimated— In 1818 by Mordecai M. Noah at 3,000 In 1824 by Solomon Etting at 6,000 In 1826 by Isaac C. Harby at 6,000 In 1840 by the American Almanac at 15,000 In 1848 by M. A. Berk at 50,000 In 1880 by Wm. B. Hackenburg at 230,257 In 1888 by Isaac Markens at 400,000 In 1897 by David Sulzberger at 937,800 In 1905 by "The Jewish Encyclopedia" at 1,508,435 In 1907 by " The American Jewish Year Book " at 1,777,185 In 1910 by " The American Je\rish Year Book" at 2,044,762 DISTRIBUTION The following table by States presents two sets of estimates. -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

4 / Midrash and History: a Key to the Babelesque Imagination

4 / Midrash and History: A Key to the Babelesque Imagination Myth as History Myth in Babelʹ’s fiction gives an illusion of the epic while mocking it, and reads unorthodox interpretations and essential truths into history. For Babelʹ, the myths of history and religion were a subtle medium for allegorical parallels, as well as ironic allusions to a moral message. This is an essentially midrashic approach to history, fol- lowing the ancient Jewish storytelling tradition that imaginatively elaborates on biblical and historical narrative, usually for exegetic or homiletic purposes, and playfully draws on intertextual, ver- bal, and semantic associations. Often new, contemporary meaning is introduced into the reading of familiar stories, or biblical ver- ses are given unexpected levels of meaning that dramatizes bib- lical figures as human. As Daniel Boyarin has demonstrated, midrash, the biblical metacommentary that forms part of Tal- mudic lore, is fundamentally intertextual and sets up a coded dua- lity between the exegetical text and the quoted or referenced pas- sage. When a textual moment is felt to be awkward, what Michel Rifattere terms “ungrammaticality” points to gaps that provide the key to decoding through another text.1 The midrashic mode informs the Jewish imagination at times of cultural repression (such as under the Romans or the Tsars), and characterizes the way the canon of Jewish literature has developed and renewed itself. There is something we might call midrashic in Babelʹ’s view of history. 129 4 / Midrash and History We may find a key to Babelʹ’s midrashic view of history in the art of the Polish painter in Red Cavalry. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Hanne Trautner-Kromann n this introduction I want to give the necessary background information for understanding the nine articles in this volume. II start with some comments on the Hebrew or Jewish Bible and the literature of the rabbis, based on the Bible, and then present the articles and the background information for these articles. In Jewish tradition the Bible consists of three main parts: 1. Torah – Teaching: The Five Books of Moses: Genesis (Bereshit in Hebrew), Exodus (Shemot), Leviticus (Vajikra), Numbers (Bemidbar), Deuteronomy (Devarim); 2. Nevi’im – Prophets: (The Former Prophets:) Joshua, Judges, Samuel I–II, Kings I–II; (The Latter Prophets:) Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezek- iel; (The Twelve Small Prophets:) Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habakkuk, Zephania, Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi; 3. Khetuvim – Writings: Psalms, Proverbs, Job, The Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther, Daniel, Ezra, Nehemiah, Chronicles I–II1. The Hebrew Bible is often called Tanakh after these three main parts: Torah, Nevi’im and Khetuvim. The Hebrew Bible has been interpreted and reinterpreted by rab- bis and scholars up through the ages – and still is2. Already in the Bible itself there are examples of interpretation (midrash). The books of Chronicles, for example, can be seen as a kind of midrash on the 10 | From Bible to Midrash books of Samuel and Kings, repeating but also changing many tradi- tions found in these books. In talmudic times,3 dating from the 1st to the 6th century C.E.(Common Era), the rabbis developed and refined the systems of interpretation which can be found in their literature, often referred to as The Writings of the Sages. -

Bernhard Felsenthal: the Zionization of a Radical Reform Rabbi

BERNHARD FELSENTHAL: THE ZIONIZATION OF A RADICAL REFORM RABBI Leon A. Jick This article traces Bernhard Felsenthal's ideological and institutional odyssey from extreme radical Reform to committed Zionism. In theface of theoverwhelming opposition of his Reform colleagues, Felsenthal endorsed and embraced the nascent Zionist movement and devoted his final years to its support. The last half of the nineteenth century was a time of turbulent ideological ferment. Amidst radical social, economic and political change, new ideologies sprouted and fractured into competing factions. Buffeted by the tides of unanticipated consequences indi vidual thinkers and activists frequently changed their positions and their affiliations. Moses Hess moved from a variety of socialisms to proto-Zionism, and Leon Pinsker from Russian assimilation to Jew ? ish nationalism. Nussan Birnbaum at one time a chief secretary to Herzl, drifted from Zionism to become general secretary of Agudat a as a en Yisrael with stopover diaspora nationalist route. Herzl himself was a convert to Zionism. At the same time, perhaps in reaction against the turmoil and uncertainty, there were elements who responded with ideological JewishPolitical Studies Review 9:1-2 (Spring 1997) 5 This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.72.231 on Tue, 20 Nov 2012 03:24:54 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 6 LeonA Jick inflexibility. The most obvious Jewish example is the Chatam Sofer whose dictum chadash asur min hatorah "innovation is forbidden from the Torah" forbade any change however trivial in traditional practice. The overwhelming preponderance of the leaders of radical Re form Judaism in Germany and in America falls into the latter category. -

Negative Shocks and Mass Persecutions: Evidence from the Black Death

Negative Shocks and Mass Persecutions: Evidence from the Black Death Remi Jedwab and Noel D. Johnson and Mark Koyama⇤ April 16, 2018 Abstract We study the Black Death pogroms to shed light on the factors determining when a minority group will face persecution. In theory, negative shocks increase the likelihood that minorities are persecuted. But, as shocks become more severe, the persecution probability decreases if there are economic complementarities between majority and minority groups. The effects of shocks on persecutions are thus ambiguous. We compile city-level data on Black Death mortality and Jewish persecutions. At an aggregate level, scapegoating increases the probability of a persecution. However, cities which experienced higher plague mortality rates were less likely to persecute. Furthermore, for a given mortality shock, persecutions were less likely in cities where Jews played an important economic role and more likely in cities where people were more inclined to believe conspiracy theories that blamed the Jews for the plague. Our results have contemporary relevance given interest in the impact of economic, environmental and epidemiological shocks on conflict. JEL Codes: D74; J15; D84; N33; N43; O1; R1 Keywords: Economics of Mass Killings; Inter-Group Conflict; Minorities; Persecutions; Scapegoating; Biases; Conspiracy Theories; Complementarities; Pandemics; Cities ⇤Corresponding author: Remi Jedwab: Associate Professor of Economics, Department of Economics, George Washington University, [email protected]. Mark Koyama: Associate -

The Anti-Samaritan Attitude As Reflected in Rabbinic Midrashim

religions Article The Anti‑Samaritan Attitude as Reflected in Rabbinic Midrashim Andreas Lehnardt Faculty of Protestant Theology, Johannes Gutenberg‑University Mainz, 55122 Mainz, Germany; lehnardt@uni‑mainz.de Abstract: Samaritans, as a group within the ranges of ancient ‘Judaisms’, are often mentioned in Talmud and Midrash. As comparable social–religious entities, they are regarded ambivalently by the rabbis. First, they were viewed as Jews, but from the end of the Tannaitic times, and especially after the Bar Kokhba revolt, they were perceived as non‑Jews, not reliable about different fields of Halakhic concern. Rabbinic writings reflect on this change in attitude and describe a long ongoing conflict and a growing anti‑Samaritan attitude. This article analyzes several dialogues betweenrab‑ bis and Samaritans transmitted in the Midrash on the book of Genesis, Bereshit Rabbah. In four larger sections, the famous Rabbi Me’ir is depicted as the counterpart of certain Samaritans. The analyses of these discussions try to show how rabbinic texts avoid any direct exegetical dispute over particular verses of the Torah, but point to other hermeneutical levels of discourse and the rejection of Samari‑ tan claims. These texts thus reflect a remarkable understanding of some Samaritan convictions, and they demonstrate how rabbis denounced Samaritanism and refuted their counterparts. The Rabbi Me’ir dialogues thus are an impressive literary witness to the final stages of the parting of ways of these diverging religious streams. Keywords: Samaritans; ancient Judaism; rabbinic literature; Talmud; Midrash Citation: Lehnardt, Andreas. 2021. The Anti‑Samaritan Attitude as 1 Reflected in Rabbinic Midrashim. The attitudes towards the Samaritans (or Kutim ) documented in rabbinical literature 2 Religions 12: 584. -

Shavuot in Talmud and Midrash (Mostly Soncino Translation and Commentary; Emphasis Mine; Some Language Tweaks)

22 May 2007 [Shavuot 5767] Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Congregation Adat Reyim Tikkun Lel Shavuot Shavuot in Talmud and Midrash (Mostly Soncino translation and commentary; emphasis mine; some language tweaks) Only Israel accepted the Torah Mechilta de Rabbi Ishmael, Exodus 20:2 It was for the following reason that the ancient nations of the world were asked to accept the Torah, in order that they should have no excuse for saying, 'Had we been asked we would have accepted it'. For, behold, they were asked and they refused to accept it, for it is said, "He said, the Lord came from Sinai...) (Deut. 33:2). He appeared to the children of Esau, the wicked, and said to them, "Will you accept the Torah?" They said to Him, "What is written in it?" He said to them, "You shall not murder" (Deut. 5:17) They then said to Him, "The very heritage which our father left us was 'By the sword you shall live' (Gen. 27:40). He then appeared to the children of Ammon and Moab. He said to them, "Will you accept the Torah?" They said to Him, "What is written in it?" He said to them, "You shall not commit adultery" (Deut. 5:17) They, however, said to Him that they were, all of them, the children of adulterers, as it is said, "Thus the two daughters of Lot came to be with child by their father" (Gen. 19:36) He then appeared to the children of Ishmael. He said to them, "Will you accept the Torah?" They said to Him, "What is written in it?" He said to them, "You shall not steal" (Deut. -

University of Zurich Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich

Oliver, I W; Bachmann, V (2009). The Book of Jubilees: An Annotated Bibliography from the First German Translation of 1850 to the Enoch Seminar of 2007. Henoch, 31(1):123-164. Postprint available at: http://www.zora.uzh.ch University of Zurich Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich. Zurich Open Repository and Archive http://www.zora.uzh.ch Originally published at: Henoch 2009, 31(1):123-164. Winterthurerstr. 190 CH-8057 Zurich http://www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2009 The Book of Jubilees: An Annotated Bibliography from the First German Translation of 1850 to the Enoch Seminar of 2007 Oliver, I W; Bachmann, V Oliver, I W; Bachmann, V (2009). The Book of Jubilees: An Annotated Bibliography from the First German Translation of 1850 to the Enoch Seminar of 2007. Henoch, 31(1):123-164. Postprint available at: http://www.zora.uzh.ch Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich. http://www.zora.uzh.ch Originally published at: Henoch 2009, 31(1):123-164. THE BOOK OF JUBILEES: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY FROM THE FIRST GERMAN TRANSLATION OF 1850 TO THE ENOCH SEMINAR OF 2007 ISAAC W. OLIVER , University of Michigan VERONIKA BACHMANN , University of Zurich The following annotated bibliography provides summaries of the most influential scholarly works dedicated to the Book of Jubilees written between 1850 and 2006. * The year 1850 opens the period of modern research on Jubilees thanks to Dillmann’s translation of the Ethiopic text of Jubilees into German; the Enoch Seminar of 2007 represents the largest gathering of international scholars on the document in modern times. -

Abbreviations and Bibliography

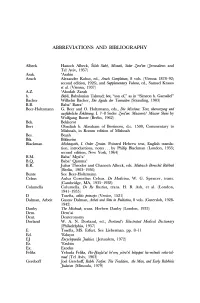

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY Albeck Hanoch Albeck, Sifah Sidre, Misnah, Seder Zera'im (Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, 1957) Arak. 'Arakin Aruch Alexander Kohut, ed., Aruch Completum, 8 vols. (Vienna 1878-92; second edition, 1926), and Supplementary Volume, ed., Samuel Krauss et al. (Vienna, 193 7) A.Z. 'Abodah Zarah b. Babli, Babylonian Talmud; ben, "son of," as in "Simeon b. Gamaliel" Bacher Wilhelm Bacher, Die Agada der Tannaiten (Strassling, 1903) B.B. Baba' Batra' Beer-Holtzmann G. Beer and 0. Holtzmann, eds., Die Mischna: Text, iiberset::;ung und ausfiihrliche Erkliirung, I. 7-8 Seder Zera'im: Maaserotl Mauser Sheni by Wolfgang Bunte (Berlin, 1962) Bek. Bekhorot Bert Obadiah b. Abraham of Bertinoro, d.c. 1500, Commentary to Mishnah, in Romm edition of Mishnah Bes. Be~ah Bik. Bikkurim Blackman Mishnayoth, I. Order Zeraim. Pointed Hebrew text, English transla tion, introductions, notes ... by Philip Blackman (London, 1955; second edition, New York, 1964) B.M. Baba' Mesi'a' B.Q Baba' Qamma' B.R. Julius Theodor and Chanoch Albeck, eds. Midrasch Bereschit Rabbah (Berlin, 1903-1936) Bunte See Beer-Holtzmann Celsus Aulus Cornelius Celsus. De Medicina, W. G. Spencer, trans. (Cambridge, MA, 1935-1938) Columella Columella. De Re Rustica, trans. H. B. Ash, et al. (London, 1941-1955) D Tosefta, editio princeps (Venice, 1521) Dalman, Arbeit Gustav Dalman, Arbeit und Sitte in Paliistina, 8 vols. (Gutersloh, 1928- 1942) Danby The Mishnah, trans. Herbert Danby (London, 1933) Dem. Dem'ai Deut. Deuteronomy Dorland W. A. N. Dorland, ed., Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (Philadelphia, 195 7) E Tosefta, MS. Erfurt. See Lieberman. pp. 8-11 Ed. -

GOES WHERE JESUS GOES Disciple – Part 1 Pastor Keith Stewart August 2, 2020

2660 Belt Line Road Garland, TX 75044 972.494.5683 www.springcreekchurch.org GOES WHERE JESUS GOES Disciple – Part 1 Pastor Keith Stewart August 2, 2020 Mimeithai means to imitate or mimic something. Tupos means pattern, example, or model. You became imitators (mimeithai) of us and of the Lord; in spite of severe suffering, you welcomed the message with the joy given by the Holy Spirit. 1 Thessalonians 1.6 Follow my example (mimeithai), as I follow the example of Christ. 1 Corinthians 11.1 We did this, not because we do not have the right to such help, but in order to offer ourselves as a model (tupos) for you to imitate. 1 Thessalonians 3.9 It’s like we’re looking for something that we’ve lost. 2660 Belt Line Road Garland, TX 75044 972.494.5683 www.springcreekchurch.org God knew what He was doing from the very beginning. He decided from the outset to shape the lives of those who love him along the same lines as the life of his Son. The Son stands first in the line of humanity He restored. We see the original and intended shape of our lives there in Him. After God made that decision of what His children should be like, He followed it up by calling people by name. After He called them by name, He set them on a solid basis with Himself. And then, after getting them established, He stayed with them to the end, gloriously completing what He had begun. Romans 8.29-30 (Message) “Christianity is making humanity what it ought to be.” – Leroy Forlines 1. -

Jews and Mormons: Two Houses of Israel Frank J. Johnson and Rabbi William J

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 41 Issue 4 Article 4 10-1-2002 Jews and Mormons: Two Houses of Israel Frank J. Johnson and Rabbi William J. Leffler David E. Bokovoy Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Bokovoy, David E. (2002) "Jews and Mormons: Two Houses of Israel Frank J. Johnson and Rabbi William J. Leffler," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 41 : Iss. 4 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol41/iss4/4 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Bokovoy: <em>Jews and Mormons: Two Houses of Israel</em> Frank J. Johnson frank J johnson and rabbi william J leffler ca 0 jews and Morcormonsmormonsmons two houses of israel 0 hoboken new york ktavkeav publishing 2000 X M M by E bokovoy reviewed david M C n addition to everything else they do words can be ambassadors of iingoodwill spreading the messages ofa culture 1 this statement by joseph lowin the director of cultural services at the national foundation for jewish culture coincides with the thesis of jews and Morcormonsmormonsmons two houses of israel jews need to know more about mormonism and cormonsmormons about judaism 131 the authors frank J johnson a mormon high priest and william J leffler a jewish rabbi undertake to explain the differences and similarities