The Politics of Cultural Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

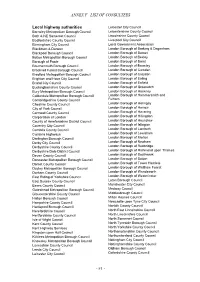

Annex F –List of Consultees

ANNEX F –LIST OF CONSULTEES Local highway authorities Leicester City Council Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council Leicestershire County Council Bath & NE Somerset Council Lincolnshire County Council Bedfordshire County Council Liverpool City Council Birmingham City Council Local Government Association Blackburn & Darwen London Borough of Barking & Dagenham Blackpool Borough Council London Borough of Barnet Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Bexley Borough of Poole London Borough of Brent Bournemouth Borough Council London Borough of Bromley Bracknell Forest Borough Council London Borough of Camden Bradford Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Croydon Brighton and Hove City Council London Borough of Ealing Bristol City Council London Borough of Enfield Buckinghamshire County Council London Borough of Greenwich Bury Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Hackney Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council London Borough of Hammersmith and Cambridgeshire County Council Fulham Cheshire County Council London Borough of Haringey City of York Council London Borough of Harrow Cornwall County Council London Borough of Havering Corporation of London London Borough of Hillingdon County of Herefordshire District Council London Borough of Hounslow Coventry City Council London Borough of Islington Cumbria County Council London Borough of Lambeth Cumbria Highways London Borough of Lewisham Darlington Borough Council London Borough of Merton Derby City Council London Borough of Newham Derbyshire County Council London -

Yorkshire and Humberside)

NOTES OF A MEETING OF THE STANDARDS COMMITTEE INDEPENDENT MEMBERS’ REGIONAL FORUM (YORKSHIRE AND HUMBERSIDE) 24 TH OCTOBER 2006 PRESENT: Mike Wilkinson - Leeds City Council Ann Becket - West Yorkshire Police Authority Martin Allingham - North East Lincolnshire Council Alan Carter - South Yorkshire Police Authority/South Yorkshire Passenger Transport Authority Gerald Burnett - Richmondshire District Council James Daglish - North Yorkshire County Council Cheryl Grant - Leeds City Council Peter Neale - Richmondshire District Council Lynn Knowles - Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council/West Yorkshire Fire and Rescue Authority John Ross - North East Derbyshire District Council Phil Marshall - West Yorkshire Fire and Rescue Authority Joyce Clarke - Humberside Fire and Rescue Authority Brian Cottingham - Kingston-upon-Hull City Council Keith Robinson - Kingston-upon-Hull City Council Dr Michael French - Harrogate Borough Council Richard Burton - South Yorkshire Police Authority William Stroud - Humberside Police Authority Mary Rose Barker - East Riding of Yorkshire Borough Council G Polley - East Riding of Yorkshire Borough Council Michael Andrew - Rotherham Metropolitan Borough Council D G Hughes - Humberside Fire and Rescue Authority IN ATTENDANCE: Amy Bowler - Secretary to the Forum, Leeds City Council 1.0 Apologies for Absence and Welcome to New Members 1.1 The following apologies for absence were reported: Denise Wilson – North Yorkshire Fire and Rescue Authority Angela Bingham – South Yorkshire Police Authority George – Wakefield Metropolitan -

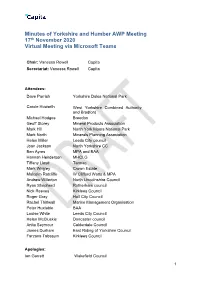

Minutes of Yorkshire and Humber AWP Meeting 17Th November 2020 Virtual Meeting Via Microsoft Teams

Minutes of Yorkshire and Humber AWP Meeting 17th November 2020 Virtual Meeting via Microsoft Teams Chair: Vanessa Rowell Capita Secretariat: Vanessa Rowell Capita Attendees: Dave Parrish Yorkshire Dales National Park Carole Howarth West Yorkshire Combined Authority and Bradford Michael Hodges Breedon Geoff Storey Mineral Products Association Mark Hill North York Moors National Park Mark North Minerals Planning Association Helen Miller Leeds City council Joan Jackson North Yorkshire CC Ben Ayres MPA and BAA Hannah Henderson MHCLG Tiffany Lloyd Tarmac Mark Wrigley Crown Estate Malcolm Ratcliffe W Clifford Watts & MPA Andrew Willerton North Lincolnshire Council Ryan Shepherd Rotherham council Nick Reeves Kirklees Council Roger Gray Hull City Council Rachel Thirlwall Marine Management Organisation Peter Huxtable BAA Louise White Leeds City Council Helen McCluskie Doncaster council Anita Seymour Calderdale Council James Durham East Riding of Yorkshire Council Farzana Tabasum Kirklees Council Apologies: Ian Garrett Wakefield Council 1 Chris Hanson Sheffield City Council Katie Gowthorpe East Riding of Yorkshire Council Vicky Perkin North Yorkshire County Council Item Description 1. Introductions and apologies 2. Minutes and actions of last meeting 3. Yorkshire & Humber AMR - ratification 4 Local Aggregate Assessments 5. Aggregate Minerals Survey update 2019 6. Planning White Paper 7. MPAs Update 8. Industry Update 9. MCHLG update 10. AOB 1. Introductions 1.1 Vanessa Rowell (VR) explained that Vicky Perkin has sent her apologies and therefore VR will be the Interim Chair for this meeting. VR Welcomed everyone to the meeting. 2. Minutes and actions of last meeting 2.1 VR went through the minutes from the last meeting asking if there were any comments on the minutes. -

Coast Capers

= Coast Capers ` By JACK DEVANEY Sonny and Cher were honored "Soulin'," has been set by Mo- WHERE IT'S AT at a cocktail party for local and town to do likewise for the new foreign press on the eve of album by the Supremes. their departure for their Euro- Mel Carter set to headline Amy Records is thrilled with the reaction on "I'm Your pean tour . LuLu Porter three Southwest concert dates Puppet," James & Bobby Purify, Bell. WVON made it the Pick opens at the Little Club this Sept. 9, 10 and 11 ... Metric's of the Week and so did WAMO, Pittsburgh. The reaction to Tuesday night . John Fish- Mike Gould and Ernie Farrell "Fannie Mae," Mighty Sam, is also tremendous, according to er's Current label out with a are having mucho success with Larry Uttal and Fred DeMann. new one-"Let's Talk About "I Chose to Sing the Blues," Instant Smash: "Said I Wasn't Gonna Tell Nobody" by Sam Girls" by the Tongues of Truth penned by Jimmy Holiday and and Dave. The driving 'Boogaloo' beat is a natural for what's .. Al Hirt will make a guest Ray Charles and recorded by happening in today's market! ... Dr. Fat Daddy did it again. appearance in the film, "What Charles ... Capitol held a jam- He broke a record in Baltimore all by himself : "I Need a Am I Bid ?," to be released this packed press conference for the Girl," Righteous Brothers, Moonglow. We kept telling you fall. Movie stars LeRoy Van Beatles prior to their KRLA- this was a hit side, and Paul proved it. -

Housing Factsheet

Disability Sheffield Information Service Housing Factsheet Disability Sheffield Information Service, The Circle, 33 Rockingham Lane, Sheffield S1 4FW Tel (0114) 253 6750 E mail: [email protected] Website: www.disabilitysheffield.org.uk 1 In this factsheet we aim to provide information and details of services that offer assistance in the search for housing that is suitable for your requirements. We have produced a separate factsheet “Equipment and Adaptations” containing information on equipment, adaptations and technology to promote independent living including adaptations for your home. Please contact us if you would like a copy. Alternatively you can download the factsheet from our website. Social Housing Sheffield City Council was one of the first areas to change to a Choice Based Lettings (CBL) system for people wanting to live in social housing. This system allows people to bid for homes that are advertised and is designed to provide more choice particularly regarding location and property type. While CBL does give people greater choice it can put vulnerable people at a disadvantage. Sheffield City Council’s Health and Housing team can offer support and assistance to vulnerable customers on request ( see later entry for details ). Sheffield City Council own approximately 43,000 properties, although not all will be accessible, for rent across the city. To view and bid for Sheffield Council and Housing Association properties you must log in or register to use the Sheffield Property Shop website, and join the housing register. More information on this process can be found on the Sheffield Council website page Register & Bid for a Council Property. -

Local Authority / Combined Authority / STB Members (July 2021)

Local Authority / Combined Authority / STB members (July 2021) 1. Barnet (London Borough) 24. Durham County Council 50. E Northants Council 73. Sunderland City Council 2. Bath & NE Somerset Council 25. East Riding of Yorkshire 51. N. Northants Council 74. Surrey County Council 3. Bedford Borough Council Council 52. Northumberland County 75. Swindon Borough Council 4. Birmingham City Council 26. East Sussex County Council Council 76. Telford & Wrekin Council 5. Bolton Council 27. Essex County Council 53. Nottinghamshire County 77. Torbay Council 6. Bournemouth Christchurch & 28. Gloucestershire County Council 78. Wakefield Metropolitan Poole Council Council 54. Oxfordshire County Council District Council 7. Bracknell Forest Council 29. Hampshire County Council 55. Peterborough City Council 79. Walsall Council 8. Brighton & Hove City Council 30. Herefordshire Council 56. Plymouth City Council 80. Warrington Borough Council 9. Buckinghamshire Council 31. Hertfordshire County Council 57. Portsmouth City Council 81. Warwickshire County Council 10. Cambridgeshire County 32. Hull City Council 58. Reading Borough Council 82. West Berkshire Council Council 33. Isle of Man 59. Rochdale Borough Council 83. West Sussex County Council 11. Central Bedfordshire Council 34. Kent County Council 60. Rutland County Council 84. Wigan Council 12. Cheshire East Council 35. Kirklees Council 61. Salford City Council 85. Wiltshire Council 13. Cheshire West & Chester 36. Lancashire County Council 62. Sandwell Borough Council 86. Wokingham Borough Council Council 37. Leeds City Council 63. Sheffield City Council 14. City of Wolverhampton 38. Leicestershire County Council 64. Shropshire Council Combined Authorities Council 39. Lincolnshire County Council 65. Slough Borough Council • West of England Combined 15. City of York Council 40. -

Review of Sheffield CC's Cost of Care Exercise 2018

Review of Sheffield City Council’s Cost of Care Exercise Consultation Report 2017 Page 111 12th January 2018 Philip Mickelborough Kingsbury Hill Fox Limited 07941 331322 K H F [email protected] www.kingsburyhillfox.com Kingsbury Hill Fox Limited Review of Sheffield City Council’s Cost of Care Exercise 2017 Contents Summary Section Page This review is of the consultation report issued by Sheffield City Council following its Cost of Care exercise in 2017. Summary It is recognised that it is in the interests of care homes and the Council that 1. The background 1 the commissioners should have an understanding of the actual cost of 2. Kingsbury Hill Fox Limited 1 providing care. 3. Alignment of interests 2 4. The Council’s methodology 3 The report is not specific about the sample used for its analysis, but it does 5. The response and the data sources 3 appear to be small and unrepresentative. 6. The analysis 6.1 Weighting 4 The analysis used unweighted averages and took no account of resident Page 112 6.2 Resident dependency levels 4 dependency levels. 6.3 Allowing for inflation 5 7. Specific costs Some of the data used in the report appear to be erroneous; in particular the 7.1 Nursing costs 5 nursing costs. 7.2 Personal care staff 5 7.3 Other costs 6 The method of calculating the notional return on capital is not independent 8. Corporate overheads 6 of the operator’s personal circumstances. 9. Rent/mortgage costs 9.1 Return on capital value/mortgage payments 7 The Council’s plans for the way in which purchases care home places are 9.2 Why not use the actual figures provided for 7 enlightened but some of its reasoning is based on sub-optimal calculations. -

SHEFFIELD CITY COUNCIL Development, Environment and Leisure Directorate

SHEFFIELD CITY COUNCIL Development, Environment and Leisure Directorate REPORT TO WEST AND NORTH PLANNING AND DATE 11/11/2008 HIGHWAYS AREA BOARD REPORT OF DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT SERVICES ITEM SUBJECT APPLICATIONS UNDER VARIOUS ACTS/REGULATIONS SUMMARY RECOMMENDATIONS SEE RECOMMENDATIONS HEREIN THE BACKGROUND PAPERS ARE IN THE FILES IN RESPECT OF THE PLANNING APPLICATIONS NUMBERED. FINANCIAL IMPLICATIONS N/A PARAGRAPHS CLEARED BY BACKGROUND PAPERS CONTACT POINT FOR Vernon Faulkner TEL 0114 2734944 ACCESS NO: AREA(S) AFFECTED CATEGORY OF REPORT OPEN 2 Application No. Location Page No. 08/02703/FUL Land And Buildings Including Corus And Outokumpu Works, 7 Ford Cottage 23 Ford Lane, 452-462 Manchester Road, Town Hall Manchester Road, Town Hall House Manchester Road And 1 Hunshelf Road Hunshelf Road Stocksbridge Sheffield 08/04538/FUL 617 Loxley Road Sheffield 31 S6 6RR 08/04639/FUL Land At Rear Of Carphone Warehouse Penistone Road North 40 Sheffield 08/04802/FUL Yews Farm Worrall Road 44 Worrall Sheffield S35 0AU 08/04746/REM 485 Loxley Road Sheffield 57 S6 6RP 08/04908/FUL Land Adjacent 42 Thrush Street 70 Sheffield 08/04958/FUL Curtilage Of 86 Bellhagg Road Sheffield 78 S6 5BS 08/04961/FUL 485 Loxley Road Sheffield 90 S6 6RP 3 08/05043/FUL Shawdene Sunny Bank Road 97 Sheffield S36 3ST 08/05419/COND Land Between Station Road & Manchester Road 102 Stocksbridge Sheffield 4 5 SHEFFIELD CITY COUNCIL Report Of The Head Of Planning, Transport And Highways, Development, Environment And Leisure To The NORTH & WEST Planning And Highways Area Board Date Of Meeting: 11/11/2008 LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS FOR DECISION OR INFORMATION *NOTE* Under the heading “Representations” a Brief Summary of Representations received up to a week before the Area Board date is given (later representations will be reported verbally). -

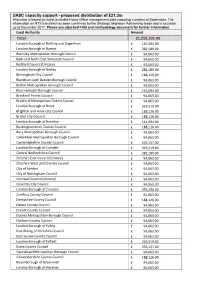

UASC Capacity Support - Proposed Distribution of £21.3M Allocation Is Based on Latest Available Home Office Management Data Capturing Numbers at September

UASC capacity support - proposed distribution of £21.3m Allocation is based on latest available Home Office management data capturing numbers at September. The information on NTS transfers has been confirmed by the Strategic Migration Partnership leads and is accurate up to December 2017. Please see attached FAQ and methodology document for further information. Local Authority Amount Total 21,258,203.00 London Borough of Barking and Dagenham £ 141,094.00 London Borough of Barnet £ 282,189.00 Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Bath and North East Somerset Council £ 94,063.00 Bedford Council (Unitary) £ 94,063.00 London Borough of Bexley £ 282,189.00 Birmingham City Council £ 188,126.00 Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Bournemouth Borough Council £ 141,094.00 Bracknell Forest Council £ 94,063.00 Bradford Metropolitan District Council £ 94,063.00 London Borough of Brent £ 329,219.00 Brighton and Hove City Council £ 188,126.00 Bristol City Council £ 188,126.00 London Borough of Bromley £ 141,094.00 Buckinghamshire County Council £ 188,126.00 Bury Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Cambridgeshire County Council £ 235,157.00 London Borough of Camden £ 329,219.00 Central Bedfordshire Council £ 282,189.00 Cheshire East Council (Unitary) £ 94,063.00 Cheshire West and Chester Council £ 94,063.00 City of London £ 94,063.00 City of Nottingham Council £ 94,063.00 Cornwall Council (Unitary) £ 94,063.00 Coventry City -

London Bids (Will Create up to 2,000 Jobs*)

Future Jobs Fund Awards - July 2009 National Bids (will create up to 8,500 jobs across Great Britain): • HCT: • Network for Black Professionals • Groundwork/ NHF • Training for Life • 3SC • Green Works • Nacro • Novas Scarman • Places for People • Pre-School Learning Alliance • RNIB • Royal Society of Wildlife Volunteers • Salvation Army London Bids (will create up to 2,000 jobs*) • Royal Borough of Kingston • Westminster City Council • East Tenders (in partnership with the London Borough of Redbridge) • Lambeth First • Call Britannia • Islington Council • Renaisi Ltd • St Mungo’s • Camden Council • London Borough of Ealing • Southwark Earn and Learn (in partnership with the London Borough of Southwark) • Host Borough Councils (Hackney, Newham, Tower Hamlets and Waltham Forest) • Lewisham Council • Social Enterprise London Partnership • London Borough of Barking and Dagenham • Southbank Centre/New Deal of the Mind • Resources Plus • Southbank Employers Group • Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea • Greenwich Council • London Youth • Croydon Economic Development Company South East Bids (will create up to 3,300 jobs) • Kent County Council • Gateway Knowledge Alliance • Thanet District Council • Brighton and Hove City Council. • Hampshire County Council • Hastings Borough Council South West Bids (will create up to 700 jobs) • Bristol City Council • Cornwall Council • Wiltshire Council East of England Bids (will create up to 1,200 jobs) • Renaissance East of England • Luton Borough Council • Norfolk County Council West Midlands Bids (will -

The Liverpool Packet

THE LIVERPOOL PACKET ]ANET E. MULLINS F the matters recorded concerning the town of Liverpool, none O compares either in point of vital interest in its time or in challenge to the imagination with that of privateering. Almost from the time of its settlement by the English this activity made its influence felt, slightly in earlier years, acutely from 1776 to 1815, in a diminishing degree since, ripples from the centre of agitation of the War of 1812 not yet having lost themselves on the shores of time. The word "privateering" suggests various things to various people; to some, a questionable mode of acquiring wealth; to others, a legalized method of harassing an enemy; to this one, piracy; to that, patriotism. The perspective afforded by time, contemporary history and newspaper files, especially those of the enemy, letters, diaries, log-books, all provide the means to de termine whether the Maritimes were justified or not in resorting to this mode of warfare. Privateers were owned, armed and equipped by private citizens and used as defenders of the coast, intelligence craft, commerce destroyers. The Liverpool privateersmen were of excellent stock, all leading citizens of their community, well and favorably known to British naval officers of the time. When the wars were over, many filled positions of honour as members of parliament, judges, ship-owners, merchants. The crews, mostly fishermen, were picked from volun teers, the success of a cruise depending on each man's ability in seamanship and his skill in the use of naval weapons. None were on wages. All fought on a share system. -

Artist Title Year Master Label Serial Number Pressed by Country Stereo

Artist Title Year Master Label Serial Number Pressed By Country Stereo-Mono Disk Condition Cover Condition Comments Abba Ring Ring 1973 RCA SL102323 AUST Stereo G slight cover wear First Adam Faith Adam 1960 Parlophone PMC-1128 UK Stereo G slight cover wear First Adventurers, The Can’ stop twisting 1966 Coronet KLL-1712 Philips NZ Stereo G G First + only Affection Collection, The The Affection Collection 1968 Evolution 2007 USA Stereo G G First + only Alice Cooper Pretties for you 1969 Straight WB-1840 Warner Brothers USA G G First-GATE FOLD Allisons, The Are you sure? 1961 Fontana STFL-558 UK Stereo G G First + only Ambrose Slade Ballzy 1969 Fontana SRF-67598 USA Stereo G G First Amen Corner Round 1968 Decca SMLM-1021 HMV NZ Stereo G G First American Breed American Breed 1967 Quality ACTA-38002 Canada Stereo G G 2 small punch holes on disc First Allied American Eagle American Eagle 1970 MCA MAP-S-4217 NZ Stereo G Slight damage on bottom back flap First+ only International Angels, The My Boyfriend's Back 1963 Philips BL-14542 Philips NZ Mono G Tape on back edge-small tear on opening Second Animals, The The Animals 1964 Columbia 33-MSX-6057 HMV NZ Mono BAD BAD Gap filler only Annette Annette 1959 Disney WDL-3301 NZ Stereo F+ Slight wear on back cover Second Aorta Aorta 1969 Columbia CS-9785 Canada Stereo G G First + only GATE FOLD Apollo 11 We have landed on the moon 1969 Capitol SREG-326 HMV NZ Stereo F+ Name and mark on back First + only Apple Pie Motherhood Band, The The Apple Pie Motherhood Band 1968 Atlantic SD-8189 USA Stereo G Remains