Come, Holy Ghost

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And Much More…

WHAT’S ON AT ST PAULS ELCOME TO ST PAUL’S. We are Monday 17th June at 7.30pm – Meditation glad that you have come to worship God with us today. If Tuesday 18th June at 1.15pm W - Lunchtime Recital - you are a visitor from another parish, or Conservatorium students worshipping with us for the first time, Tuesday 18th June at 7.30pm please introduce yourself to our parish - Study Group in the Rectory priest, Fr James Collins, or to anyone Friday 21 June at 7.30pm in wearing a name badge, over a cup of tea the church - A Cantata for Refugee week By Glenn or coffee in the parish hall after the service. McKenzie You’ll find the hall behind the church. Sunday 23rd June - Artisans’ Market 圣公会圣保罗堂欢迎你前来参加我们的英语传 Tuesday 25th June at 1.15pm 统圣樂圣餐崇拜。 - Lunchtime Recital - HSC Performance students SUNDAY 16th June 2019 from MLC - FREE CONCERT Trinity SUNDAY - The Feast of the Most Glorious And Tuesday 2nd July at 1.15pm Undivided Trinity Lunchtime Recital - Brian Kim Welcome to worship... - Flautist 8.00 am – Sung Eucharist Tuesday 23rd July at 1.15pm - Lunchtime Recital -Joshua 9.30 am – Procession and Solemn Eucharist & Ryan, Assistant Organist, Holy Baptism St Mary’s Cathedral Sydney Tuesday 20th August at 1.15pm - Lunchtime Recital - Included in this issue … Conservatorium Students Congratulations to the newly baptised P.3 Tuesday 10th September at 1.15pm - Lunchtime Recital - Fruit wanted p.6 Sydney Clarinet Choir - Deborah de Graaff Bread Roster p.10 Saturday 21st of September at 1pm - Blue Illusion Fundraiser And Much More… 1 Things you may need to know Getting inside First Aid People needing wheelchair access can enter St Paul’s most conveniently by the First aid kits are located on the wall of door at the base of the belltower. -

CH 527 COURSE SYLLABUS the MEDIEVAL CHURCH and the REFORMATION from the Rise of Charlemagne to the Council of Trent Fall, 2020

CH 527 COURSE SYLLABUS THE MEDIEVAL CHURCH and THE REFORMATION From the Rise of Charlemagne to The Council of Trent Fall, 2020. Instructor: Fr. Luke Dysinger, OSB. Email: [email protected]. Phone: 805 482-2755: office ext 1045; room ext. 1068. Office Hours (St. Katharine 318) by arrangement, COURSE WEBSITE: through Sonis, or http://ldysinger.stjohnsem.edu DESCRIPTION: This course will introduce the history, theology, and spirituality of the Christian Church from the rise of Charlemagne (c. 800) to the Council of Trent (1563). This course will provide an overview of both the theological and spiritual traditions of the Medieval Church through the time of the Catholic Reformation, culminating in the Council of Trent. The rich ethnic and cultural diversity of Christian thought during this period will be highlighted through study of primary sources from the Jewish, Roman, Greek, Celtic, Anglo- European, Slavic, Middle-Eastern (Syriac), and Egyptian (Coptic) traditions. In order to profit from the cultural and ethnic diversity of the student body, students are encouraged to bring to classroom discussion the early and medieval origins of their cultural traditions: including, for example, the theological, liturgical, and spiritual emphases that distinguish Western Catholicism from Eastern traditions such as the Maronite, Chaldean, Melchite, Malabar, and Ruthenian churches. During each class selected primary and secondary texts will be studied and discussed. A large proportion of the primary texts will be taken from the Office of Readings. In this way students’ ongoing prayerful study of these texts in the liturgy will provide a deepening re-acquaintance with patristic and early medieval sources of Christian spirituality and doctrine. -

University Microfilms International T U T T L E , V Ir G in Ia G R a C E

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material subm itted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again-beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

Doctrinal Controversies of the Carolingian Renaissance: Gottschalk of Orbais’ Teachings on Predestination*

ROCZNIKI FILOZOFICZNE Tom LXV, numer 3 – 2017 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18290/rf.2017.65.3-3 ANDRZEJ P. STEFAŃCZYK * DOCTRINAL CONTROVERSIES OF THE CAROLINGIAN RENAISSANCE: GOTTSCHALK OF ORBAIS’ TEACHINGS ON PREDESTINATION* This paper is intended to outline the main areas of controversy in the dispute over predestination in the 9th century, which shook up or electrified the whole world of contemporary Western Christianity and was the most se- rious doctrinal crisis since Christian antiquity. In the first part I will sketch out the consequences of the writings of St. Augustine and the revival of sci- entific life and theological and philosophical reflection, which resulted in the emergence of new solutions and aporias in Christian doctrine—the dispute over the Eucharist and the controversy about trina deitas. In the second part, which constitutes the main body of the article, I will focus on the presenta- tion of four sources of controversies in the dispute over predestination, whose inventor and proponent was Gottschalk of Orbais, namely: (i) the concept of God, (ii) the meaning of grace, nature and free will, (iii) the rela- tion of foreknowledge to predestination, and (iv) the doctrine of redemption, i.e., in particular, the relation of justice to mercy. The article is mainly an attempt at an interpretation of the texts of the epoch, mainly by Gottschalk of Orbais1 and his adversary, Hincmar of Reims.2 I will point out the dif- Dr ANDRZEJ P. STEFAŃCZYK — Katedra Historii Filozofii Starożytnej i Średniowiecznej, Wy- dział Filozofii Katolickiego Uniwersytetu Lubelskiego Jana Pawła II; adres do korespondencji: Al. -

'It Is Bread and It Is Christ's Body Too': Presence and Sacrifice in The

‘It is Bread and it is Christ’s Body Too’: Presence and Sacrifice in the Eucharistic Theology of Jeremy Taylor Paul Andrew Barlow PhD, MA, BSc, PGCE A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dublin City University Supervisor: Dr Joseph Rivera School of Theology, Philosophy and Music July 2019 ii I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Doctor of Philosophy is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed: ID No.:15212014 Date: 15th July 2019 iii iv And yet if men would but do reason, there were in all religion no article which might more easily excuse us from meddling with questions about it than this of the holy sacrament. For as the man in Phaedrus that being asked what he carried hidden under his cloak, answered, it was hidden under his cloak; meaning that he would not have hidden it but that he intended it should be secret; so we may say in this mystery to them that curiously ask what or how it is, mysterium est, ‘it is a sacrament and a mystery;’ by sensible instruments it consigns spiritual graces, by the creatures it brings us to God, by the body it ministers to the Spirit. -

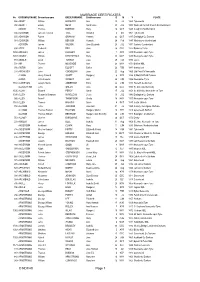

MARRIAGE CERTIFICATES © NDFHS Page 1

MARRIAGE CERTIFICATES No GROOMSURNAME Groomforename BRIDESURNAME Brideforename D M Y PLACE 588 ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul 1869 Tynemouth 935 ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 JUL 1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16 OCT 1849 Coughton Northampton 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth 655 ADAMSON Robert GRAHAM Hannah 23 OCT 1847 Darlington Co Durham 581 ADAMSON William BENSON Hannah 24 Feb 1847 Whitehaven Cumberland ADDISON James WILSON Jane Elizabeth 23 JUL 1871 Carlisle, Cumberland 694 ADDY Frederick BELL Jane 26 DEC 1922 Barnsley Yorks 1456 AFFLECK James LUCKLEY Ann 1 APR 1839 Newcastle upon Tyne 1457 AGNEW William KIRKPATRICK Mary 30 MAY 1887 Newcastle upon Tyne 751 AINGER David TURNER Eliza 28 FEB 1870 Essex 704 AIR Thomas MCKENZIE Ann 24 MAY 1871 Belford NBL 936 AISTON John ELLIOTT Esther 26 FEB 1881 Sunderland 244 AITCHISON John COCKBURN Jane 22 Aug 1865 Utd Pres Ch Newcastle ALBION Henry Edward SCOTT Margaret 6 APR 1884 St Mark Millfield Durham ALDER John Cowens WRIGHT Ann 24 JUN 1856 Newcastle /Tyne 1160 ALDERSON Joseph Henry ANDERSON Eliza 22 JUN 1897 Heworth Co Durham ALLABURTON John GREEN Jane 24 DEC 1842 St. Giles ,Durham City 1505 ALLAN Edward PERCY Sarah 17 JUL 1854 St. Nicholas, Newcastle on Tyne 1390 ALLEN Alexander Bowman WANDLESS Jessie 10 JUL 1943 Darlington Co Durham 992 ALLEN Peter F THOMPSON Sheila 18 MAY 1957 Newcastle upon Tyne 1161 ALLEN Thomas HIGGINS Annie 4 OCT 1887 South Shields 158 ALLISON John JACKSON Jane Ann 31 Jul 1859 Colliery, Catchgate, -

EB WARD Diary

THE DIARY OF SAMUEL WARD, A TRANSLATOR OF THE 1611 KING JAMES BIBLE Transcribed and prepared by Dr. M.M. Knappen, Professor of English History, University of Chicago. Edited by John W. Cowart Bluefish Books Cowart Communications Jacksonville, Florida www.bluefishbooks.info THE DIARY OF SAMUEL WARD, A TRANSLATOR OF THE 1611 KING JAMES BIBLE. Copyright © 2007 by John W. Cowart. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America by Lulu Press. Apart from reasonable fair use practices, no part of this book’s text may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address Bluefish Books, 2805 Ernest St., Jacksonville, Florida, 32205. Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data has been applied for. Lulu Press # 1009823. Bluefish Books Cowart Communications Jacksonville, Florida www.bluefishbooks.info SAMUEL WARD 1572 — 1643 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION …………………………………..…. 1 THE TWO SAMUEL WARDS……………………. …... 13 SAMUEL WARD’S LISTIING IN THE DICTIONARY OF NATIONAL BIOGRAPHY…. …. 17 DR. M.M. KNAPPEN’S PREFACE ………. …………. 21 THE PURITAN CHARACTER IN THE DIARY. ….. 27 DR. KNAPPEN’S LIFE OF SAMUEL WARD …. …... 43 THE DIARY TEXT …………………………….……… 59 THE 1611 TRANSLATORS’ DEDICATION TO THE KING……………………………………….… 97 THE 1611 TRANSLATORS’ PREFACE TO BIBLE READERS ………………………………………….….. 101 BIBLIOGRAPHY ……………………………….…….. 129 INTRODUCTION by John W. Cowart amuel Ward, a moderate Puritan minister, lived from 1572 to S1643. His life spanned from the reign of Britain’s Queen Elizabeth, through that of King James. and into the days of Charles I. Surviving pages of Ward’s dated diary entries run from May 11, 1595, to July 1, 1632. -

December-2015-Januar

THE CLARION The Magazine of The Parish of St Mary The Boltons rooted in faith • open in thought • reaching out in service December/January 2015/16 ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ St Mary’s: what you thought spend more time in contemplation and seeing As you know, I asked early on what people people one to one. A place to give thanks and liked about St Mary’s and what they would like spend time in silence. to see differently, and below are the edited highlights from the ten people who responded The central churchmanship. All are welcome. about what they liked. The lovely church itself, not too big, not too small, and still having pews… I like the vicar. I A place where one is stimulated to think about like the service, it is at a convenient time… something differently… I enjoy the formality of Open in thought, belief unconstrained by the traditional language… gracious uncluttered dogma or ordered set of prejudices. church, with a balance in form and colour… a congregation of intelligent, professional people Lovely service; thank you… I like the traditional of all ages: not exclusive, open and warm… you form of worship and the friendly, welcoming can talk to people but you don’t have to be atmosphere… Likes: welcoming, sociable, and best friends: if you needed something you could families. Spiritual guidance. An open church to the ask someone and if they can help they will, or -

The British Delegation and the Synod of Dort (1618-1619)

THE BRITISH DELEGATION AND THE SYNOD OF DORT (1618-1619) EDITED BY Anthony Milton THE BOYDELL PRESS CHURCH OF ENGLAND RECORD SOCIETY Contents Preface xi Abbreviations xiii Introduction xvii Note on Documents and Editorial Conventions lvi Part One: The Political Background to the Synod Introduction 1 1/1 King James I to the States General, 6/16 March 1613 3 1/2 Conversation of Sir Dudley Carleton with Johan van 4 Oldenbarnevelt, February 1617 1/3 King James I to the States General, 20/30 March 1617 6 1/4 Archbishop Abbot to Sir Dudley Carleton, 22 March/ 8 1 April 1617 1/5 King James I to Sir Dudley Carleton, 12/22 July 1617 10 1/6 Sir Dudley Carleton to King James I, 12/22 August 1617 10 1/7 Sir Ralph Winwood to Sir Dudley Carleton, 27 August/ 12 6 September 1617 1/8 Conversation of Sir Dudley Carleton with Hugo Grotius, 13 September 1617 1/9 Speech of Sir Dudley Carleton in the Assembly of the States 16 General, 26 September/ 6 October 1617 1/10 Earl of Buckingham to Sir Dudley Carleton, 31 October/ 20 10 November 1617 1/11 Bishop Mountagu of Winchester to Sir Dudley Carleton, 21 1/16 November 1617 1/12 Archbishop Abbot to Sir Dudley Carleton, 28 December 1617/ 22 7 January 1618 . 1/13 Archbishop Abbot to Sir Dudley Carleton, 8/18 January 1618 25 1/14 Sir Dudley Carleton to Sir Robert Naunton, 4/14 February 1618 28 1/15 The States General to King James I, 15/25 June 1618 30 1/16 Prince of Orange to Sir Dudley Carleton, 1/11 July 1618 32 1/17 Gerson Bucerus to King James I, 23 June/ 3 July 1618 33 1/18 John Young to Gerson Bucerus, 20/30 July 1618 '"37 1/19 Response to Bucerus' letter, c. -

The 1641 Lords' Subcommittee on Religious Innovation

A “Theological Junto”: the 1641 Lords’ subcommittee on religious innovation Introduction During the spring of 1641, a series of meetings took place at Westminster, between a handful of prominent Puritan ministers and several of their Conformist counterparts. Officially, these men were merely acting as theological advisers to a House of Lords committee: but both the significance, and the missed potential, of their meetings was recognised by contemporary commentators and has been underlined in recent scholarship. Writing in 1655, Thomas Fuller suggested that “the moderation and mutual compliance of these divines might have produced much good if not interrupted.” Their suggestions for reform “might, under God, have been a means, not only to have checked, but choked our civil war in the infancy thereof.”1 A Conformist member of the sub-committee agreed with him. In his biography of John Williams, completed in 1658, but only published in 1693, John Hacket claimed that, during these meetings, “peace came... near to the birth.”2 Peter Heylyn was more critical of the sub-committee, in his biography of William Laud, published in 1671; but even he was quite clear about it importance. He wrote: Some hoped for a great Reformation to be prepared by them, and settled by the grand committee both in doctrine and discipline, and others as much feared (the affections of the men considered) that doctrinal Calvinism being once settled, more alterations would be made in the public liturgy... till it was brought more near the form of Gallic churches, after the platform of Geneva.3 A number of Non-conformists also looked back on the sub-committee as a missed opportunity. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The Eucharistic liturgy in the English independent, or congregational, tradition: a study of its changing structure and content 1550 - 1974 Spinks, Bryan D. How to cite: Spinks, Bryan D. (1978) The Eucharistic liturgy in the English independent, or congregational, tradition: a study of its changing structure and content 1550 - 1974, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9577/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 BRYAN D. SPINKS THE EUCHARISTIC LITURGY. IN THE ENGLISH INDEPENDENT. OR CONGREGATIONAL,. TRADITION: A STUDY OF ITS CHANGING- STRUCTURE AND CONTENT 1550 - 1974 B.D.-THESIS 1978' The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Chapter .17 of this thesis is based upon part of an unpublished essay 1 The 1'apact of the Liturgical Movement on ii'ucharistic Liturgy of too Congregational Church in Jiu gland and Wales ', successfully presented for the degree of Master of Theology of the University of London, 1972. -

Catalogue 2017

Adopt a Book Catalogue 2017 1. Claudius Ptolomaeus, Geographia; Venice, 1562 – H.III.16 In his Geographia, Greek astronomer and polymath Claudius Ptolemy offered instruction in laying out maps by three different methods of projection; provided coordinates for some eight thousand places; and treated such basic concepts as geographical latitude and longitude. A best seller both in the age of luxurious manuscripts and in that of print, Ptolemy's Geography became one of the most influential cartographical manuals in history. Maps based on scientific principles had been produced in Europe as early as the 3rd century B.C.; however, Ptolemy’s work was different in that it offered instruction in the art of map projection. Its translation, first into Arabic in the 9th century, and then later into Latin in the 14th century, was seen as strongly influencing the cartographic traditions of both the Medieval Caliphate and Renaissance Europe. Columbus – one of its many readers – found inspiration in Ptolemy's exaggerated value for the size of Asia for his own fateful journey to the west. It was a key source for the maps of prominent cartographers including Martellus and Waldseemueller. ADOPTED £80 2. John Shute Barrington, Theological Works; London, 1828 – Q.X.62-64 The Barrington who authored this work is not the Shute Barrington who would serve as Bishop of Durham over a thirty five year period (who also published extensively on matters theological), but rather his father, John Shute Barrington, the 1st Viscount Barrington, a “politician and Christian apologist”. Barrington began publishing his theological works anonymously in 1701, with the publication of his essay concerning England and its Protestant dissidents; later editing this and publishing it under his own name, he followed it with works on The rights of Protestant dissenters and later, A dissuasive from Jacobitism.