How a Font Can Respect Basic Rules of Arabic Calligraphy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of Kufic Script in Islamic Calligraphy and Its Relevance To

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1999 A study of Kufic script in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century Enis Timuçin Tan University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Tan, Enis Timuçin, A study of Kufic crs ipt in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1999. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/1749 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. A Study ofKufic script in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century. DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by ENiS TIMUgiN TAN, GRAD DIP, MCA FACULTY OF CREATIVE ARTS 1999 CERTIFICATION I certify that this work has not been submitted for a degree to any university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, expect where due reference has been made in the text. Enis Timucin Tan December 1999 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I acknowledge with appreciation Dr. Diana Wood Conroy, who acted not only as my supervisor, but was also a good friend to me. I acknowledge all staff of the Faculty of Creative Arts, specially Olena Cullen, Liz Jeneid and Associate Professor Stephen Ingham for the variety of help they have given to me. -

A Study of Sufis and Sufi Symbolism in Ottoman Miniature Paintings

Student Publications Student Scholarship Fall 2013 Where Have All the Symbols Gone?: A Study of Sufis and Sufi yS mbolism in Ottoman Miniature Paintings Jesse E. Siegel Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the European History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Siegel, Jesse E., "Where Have All the Symbols Gone?: A Study of Sufis and Sufi yS mbolism in Ottoman Miniature Paintings" (2013). Student Publications. 192. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/192 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/ 192 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Where Have All the Symbols Gone?: A Study of Sufis and Sufi yS mbolism in Ottoman Miniature Paintings Abstract Ottoman miniature paintings represent some of the best preserved and documented works of Islamic art still extant. They differ critically from other forms of miniature painting, such as Persian miniature painting, by not representing Sufi symbolism. In the two potential sources of such symbolism, Ottoman Sufism and Persian miniature painters in the Ottoman Empire, appear to have not critically influenced Ottoman miniature painting to produce Sufi symbols, do to political, religious, and cultural factors. -

9789004165403.Pdf

The Arabic Manuscript Tradition Supplement Handbook of Oriental Studies Section 1, The Near and Middle East Editors H. Altenmüller B. Hrouda B.A. Levine R.S. O’Fahey K.R. Veenhof C.H.M. Versteegh VOLUME 95 The Arabic Manuscript Tradition A Glossary of Technical Terms and Bibliography – Supplement By Adam Gacek LEIDEN • BOSTON 2008 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gacek, Adam. The Arabic manuscript tradition : a glossary of technical terms and bibliography : supplement / by Adam Gacek. p. cm. — (Handbook of Oriental studies. Section 1, the Near and Middle East) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-16540-3 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Manuscripts, Arabic—History—Bibliography. 2. Codicology—Dictionaries. 3. Arabic language—Dictionaries—English. 4. Paleography, Arabic—Bibliography. I. Title. II. Series. Z6605.A6G33 2001 Suppl. 011'.31—dc22 2008005700 ISSN 0169–9423 ISBN 978 90 04 16540 3 Copyright 2008 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. PRINTED IN THE NETHERLANDS CONTENTS Transliteration table ....................................................................... -

Shifting Sands of Writing Inks in Yemen. the Occurrence of Sparkling

Chroniques du Manuscrit au Yémen عدد ٧ )٢٦(، يوليو ٢٠١۸ N° 7 (26) / Juillet 2018 Directrice de la Publication Anne REGOURD Contact Secrétariat [email protected] Comité de rédaction Tamon BABA (Université de Kyushu, Japon), Jan THIELE (Centro de Ciencias Humanas y Sociales, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Madrid), Anne REGOURD Revue de presse Maxim YOSEFI (Université de Göttingen) Conseil de rédaction Geoffrey KHAN (Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, Université de Cambridge (GB)), Martha M. MUNDY (The London School of Economics and Political Science, Dépt d’anthropologie), Jan RETSÖ (Université de Gothenburg, Dépt de langues et littératures, Suède), Sabine SCHMIDTKE (Institute for Ad- vanced Study, Princeton) Correspondants Tamon BABA (Université de Kyushu, Japon), Deborah FREEMAN-FAHID (FRAS, Assistant Con- servateur, Dir. de publication, The al-Sabah Collection, Dar al-Athar al-Islamiyyah, Koweït), Stéphane IPERT (Res- ponsable Préservation & Conservation, Qatar National Library), Abdullah Yahya AL SURAYHI (Manuscrits, Université d’Abu Dhabi, Bibliothèque nationale, Abu Dhabi) Comité de lecture Hassan F. ANSARI (Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton), Anne K. BANG (Université de Bergen, Norvège), Marco DI BELLA (Indépendant, Conservation/restauration manuscrits arabes), Deborah FREEMAN- FAHID (FRAS, Assistant Conservateur, Dir. de publication, The al-Sabah Collection, Dar al-Athar al-Islamiyyah, Ko- weït), David G. HIRSCH (Advisor for Library Services, Mohammed bin Rashid Library, Dubai), Michaela HOFFMANN- -

The Qur'an and Islamic

The Qur’an and Islamic Art Objectives As a result of this lesson, students will be able to: • explain how the Qur’anic prohibition of idolatry affects Islamic art. • define basic terms - Qur’an, tawhid, shirk, idolatry, Arabic, calligraphy, calligram • use the calligram form to express an idea or image for themselves • analyze how the Qur’an and Muslim culture have had impact upon the forms, techniques, and purposes of artistic work; explain the historical, cultural, and social context of representative works of Muslim calligraphy, e.g. a sultan’s seal, a contemporary calligram, a verse of the Qur’an, the name of Allah. (Meets PA Standards for the Arts and Humanities 9.2 A, C, E) Materials Student Handout: Art and the Qur’an Key Questions • What is the Qur’an? • How does it influence Muslim culture? • What does it have to say about images? • How does this affect artists? • How have Muslim artists learned to express themselves while remaining true to their faith? • How has the development of calligraphy affected the decorative arts? Sources Suggested Readings • Annemarie Schimmel. Calligraphy and Islamic Culture • Abdelkebir Khatibi and Mohammed Sijelmassi Hudson. The Splendour of Islamic Calligraphy Websites • There are many images of Islamic calligraphy to be found on-line with a simple Google search. • The Wikipedia entry under Islamic Calligraphy is substantial and contains an animated tughra explaining the writing. Continued on next page 43 Activities 1. Begin by exploring the idea of “image” – how could you describe someone you love if you could not show a picture? 2. Ask what students know about Islam, Muslim culture, the Qur’an. -

"Three Unpublished Pen Boxes Preserved in the Museum of the Faculty of Applied Arts –Helwan University – Egypt- Analytical Artistic Study"

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 22, Issue 12, Ver. 8 (December. 2017) PP 63-75 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org "Three Unpublished Pen Boxes Preserved in the Museum of the Faculty of Applied Arts –Helwan University – Egypt- Analytical Artistic Study" Dr. Ghadeer Dardier Afify Khalifa Associate Professor - Islamic Department- Faculty of Archaeology-Fayoum University, Al- Fayoum, Egypt. Corresponding Author: Dr. Ghadeer Dardier Afify Khalifa Abstract: The Pen is a mean of science, learning, and transferring science, where Allah Ta'ala explained of what is concerning of the Pen or "by the pen" in the fourth verse of Sūrat al-ʻAlaq. This is like Allah's saying; "Who has taught by the pen". Ibn al-Qayyim-may Allah have mercy- said; "with pen, science is immortal and without writing, the news of some of the times is interrupted". From here, the importance of the pen and the pen boxes were specified, as well as the attention for the quality of the raw material from which pen were manufactured, likewise the variety of ornament and materials used in decoration. So, the analytical and artistic study of the three unpublished pen boxes preserved in the Museum of the faculty of Applied Arts -Helwan University will reflect and clarify the value and importance of the scientific life in Islamic Egypt. Keywords: Pen Boxes, Raw Material, Ornament, Metalworks, Woodwork, Floral motifs, Inscriptions. --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Date of Submission: 05-12-2017 Date of acceptance: 29-12-2017 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- I. INTRODUCTION The pen is a mean of science, learning, and transferring science, where Allah Ta'ala described and explained of what is concerning of the Pen or by the pen in Sūrat al-ʻAlaq. -

Geometric Patterns and the Interpretation of Meaning: Two Monuments in Iran

BRIDGES Mathematical Connections in Art, Music, and Science Geometric Patterns and the Interpretation of Meaning: Two Monuments in Iran Carol Bier Research Associate, The Textile Museum 2320 S Street, NW Washington, DC 20008 [email protected] Abstract The Alhambra has often served in the West as the paradigm for understanding geometric pattern in Islamic art. Constructed in Spain in the 13th century as a highly defended palace, it is a relatively late manifestation of an Islamic fascination with geometric pattern. Numerous earlier Islamic buildings, from Spain to India, exhibit extensive geometric patterning, which substantiate a mathematical interest in the spatial dimension and its manifold potential for meaning. This paper examines two monuments on the Iranian plateau, dating from the 11 th century of our era, in which more than one hundred exterior surface areas have received patterns executed in cut brick. Considering context, architectural function, and accompanying inscriptions, it is proposed that the geometric patterns carry specific meanings in their group assemblage and combine to form a programmatic cycle of meanings. Perceived as ornamental by Western standards, geometric patterns in Islamic art are often construed as decorative without underlying meanings. The evidence presented in this paper suggests a literal association of geometric pattern with metaphysical concerns. In particular, the argument rests upon an interpretation of the passages excerpted from the Qur' an that inform the patterns of these two buildings, the visual and verbal expression mutually reinforcing one another. Specifically, the range and mUltiplicity of geometric patterns may be seen to represent the Arabic concept of mithal, usually translated as parable or similitude. -

Nastaleeq: a Challenge Accepted by Omega

Nastaleeq: A challenge accepted by Omega Atif Gulzar, Shafiq ur Rahman Center for Research in Urdu Language Processing, National University of Computer and Emerging Sciences, Lahore, Pakistan atif dot gulzar (at) gmail dot com, shafiq dot rahman (at) nu dot edu dot pk Abstract Urdu is the lingua franca as well as the national language of Pakistan. It is based on Arabic script, and Nastaleeq is its default writing style. The complexity of Nastaleeq makes it one of the world's most challenging writing styles. Nastaleeq has a strong contextual dependency. It is a cursive writing style and is written diagonally from right to left. The overlapping shapes make the nuqta (dots) and kerning problem even harder. With the advent of multilingual support in computer systems, different solu- tions have been proposed and implemented. But most of these are immature or platform-specific. This paper discuses the complexity of Nastaleeq and a solution that uses Omega as the typesetting engine for rendering Nastaleeq. 1 Introduction 1.1 Complexity of the Nastaleeq writing Urdu is the lingua franca as well as the national style language of Pakistan. It has more than 60 mil- The Nastaleeq writing style is far more complex lion speakers in over 20 countries [1]. Urdu writing than other writing styles of Arabic script{based lan- style is derived from Arabic script. Arabic script has guages. The salient features`r of Nastaleeq that many writing styles including Naskh, Sulus, Riqah make it more complex are these: and Deevani, as shown in figure 1. Urdu may be • Nastaleeq is a cursive writing style, like other written in any of these styles, however, Nastaleeq Arabic styles, but it is written diagonally from is the default writing style of Urdu. -

You May View It Or Download a .Pdf Here

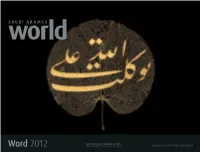

“I put my trust in God” (“Tawakkaltu ‘ala ’illah”) Word 2012 —Arabic calligraphy in nasta’liq script on an ivy leaf 42976araD1R1.indd 1 11/1/11 11:37 PM Geometry of the Spirit WRITTEN BY DAVID JAMES alligraphy is without doubt the most original con- As well, there were regional varieties. From Kufic, Islamic few are the buildings that lack Hijazi tribution of Islam to the visual arts. For Muslim cal- Spain and North Africa developed andalusi and maghribi, calligraphy as ornament. Usu- Cligraphers, the act of writing—particularly the act of respectively. Iran and Ottoman Turkey both produced varie- ally these inscriptions were writing the Qur’an—is primarily a religious experience. Most ties of scripts, and these gained acceptance far beyond their first written on paper and then western non-Muslims, on the other hand, appreciate the line, places of origin. Perhaps the most important was nasta‘liq, transferred to ceramic tiles for Kufic form, flow and shape of the Arabic words. Many recognize which was developed in 15th-century Iran and reached a firing and glazing, or they were that what they see is more than a display of skill: Calligraphy zenith of perfection in the 16th century. Unlike all earlier copied onto stone and carved is a geometry of the spirit. hands, nasta‘liq was devised to write Persian, not Arabic. by masons. In Turkey and Per- The sacred nature of the Qur’an as the revealed word of In the 19th century, during the Qajar Dynasty, Iranian sia they were often signed by Maghribıi God gave initial impetus to the great creative outburst of cal- calligraphers developed from nasta‘liq the highly ornamental the master, but in most other ligraphy that began at the start of the Islamic era in the sev- shikastah, in which the script became incredibly complex, con- places we rarely know who enth century CE and has continued to the present. -

Art History 101 Calligraphy Lesson Plan by Rudy Navarro Learning Objectives

Art History 101 Calligraphy lesson plan By Rudy Navarro Learning objectives 1. Recall that calligraphy is one of the three design elements in Islamic art 2. Distinguish between Kufic and cursive styles of calligraphy 3. Recall the principles of calligraphic aesthetics a. Calligraphy is the most important of the three design elements in Islamic art b. Calligraphy is beautiful writing c. In calligraphy, the word is also an image d. Koranic calligraphy’s beauty is meant to express the divinity of God’s word e. Koranic calligraphy embodies the beauty that is God. f. The calculated proportions of calligraphic scripts reflects the harmony and order of God and God’s creation. 4. Demonstrate knowledge of Arabic orthography a. Reading from right to left b. Letter position c. Letter connection Introduction Of all the artistic practices of Islam, calligraphy is the most important. Not only has calligraphy been highly aestheticized and systematized by Islamic artists over the centuries, but when used to transcribe the teachings of God in the Koran, calligraphy is charged with religious and spiritual power. If purity of writing is purity of the soul, according to the Arabic proverb, then calligraphy is the means to achieve that state of piety. In this module you will learn the aesthetic and cultural principles of Islamic calligraphy and the basics of Arabic writing so that you can better understand what you are seeing when you look at Islamic calligraphy. You won't be learning Arabic, but just the basic logic of how the written language works. In class you will get some experience writing in Arabic and creating your own calligraphy with traditional reed pens. -

Patterns of Complexity: Art and Design of Morocco and Tunisia 2011 2

Patterns of Complexity: The Art and Design of Morocco and Tunisia Fulbright-Hays Seminar Abroad Curriculum Project 2011 Sue Uhlig, Continuing Lecturer in Art and Design at Purdue University Religious Diversity in the Maghreb From June 12 to July 21, 2011, I was one of sixteen post-secondary educators who participated in the Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad program to Morocco and Tunisia. During those six weeks, we were immersed in the culture of the two North African countries, visiting significant historical and cultural attractions, attending lectures daily, tasting regional cuisine, and taking Arabic language classes for the first two weeks. The topic of the seminar was “Religious Diversity in the Maghreb: Morocco and Tunisia,” so lectures were focused primarily on Islamic topics, such as Moroccan Islam and Sufism, with some topics covering Judaism. We were treated to two musical performances, one relating to Judeo-Spanish Moroccan narrative songs and the other by Gnawa musicians. Visits to Christian churches, Jewish museums and synagogues, and Islamic mosques rounded out the religious focus. The group was in Morocco for a total of four weeks and Tunisia for two. In Morocco, we visited the cities of: Rabat* Casablanca* Sale Beni Mellal* Fes* Azilal Volubilis Amezray* Moulay Idriss Zaouia Ahansal Sefrou Marrakech* Ifrane In Tunisia, we visited the following cities: Tunis* Monastir Carthage Mahdia* Sidi Bou Said El Jem La Marsa Sfax Kairouan Kerkennah Islands* Sousse* Djerba* * cities with an overnight stay For more information, you may contact me at [email protected]. I also have my photos from this seminar on Flickr. http://www.flickr.com/photos/25315113@N08/ Background Being an art educator, teaching art methods classes to both art education and elementary education majors, as well as teaching a large lecture class of art appreciation to a general student population, I wanted to focus on the art and design of Morocco and Tunisia for this curriculum project. -

Midad: the Public & Intimate Lives of Arabic Calligraphy

Midad: The Public & Intimate Lives of Arabic Calligraphy 12/04 - 12/10 . 2017 Midad: The Public & Intimate Lives of Arabic Calligraphy Midad: The Public & Intimate Lives of Arabic Calligraphy MIDAD Midad investigates the ways in which Arabic THE PUBLIC calligraphy has throughout history mirrored AND INTIMATE notions of the public and private, the political LIVES OF ARABIC CALLIGRAPHY and personal, the performative and poetic, as well as the literary environments of its time. Unbound to chronology or geography, Midad explores Arabic script’s development, transformation and diverse application over time and across the world. Beyond the texts they contain, manuscripts, panels, ceramics, textiles and tools are objects that have been redefined by a process of circulation in different social, geographic and cultural contexts of history. The inaugural exhibition of the El-Nimer Curated by Collection, Midad presents over 75 pieces Rachel Dedman, and researched from the eighth to the twentieth centuries by Dr. Alain alongside five new commissions from Fouad George contemporary artists. Dar El-Nimer for Arts & Culture Midad: The Public & Intimate Lives of Arabic Calligraphy The Arabic script is a late form of Aramaic, the ancient script from which the Syriac and Hebrew alphabets also emerged. More THE specifically it is an offshoot of Nabataean, the written form of the Aramaic dialect of DEVELOPMENT Petra, in modern Jordan, and the surrounding OF ARABIC region. This strain of Nabataean eventually SCRIPT generated the alphabet we know as Arabic, a century or so before the birth of Islam. With the rise of Islam from the seventh century AD, the practice of calligraphy evolved to give visual form to the Qur’an, the word of God, and to preserve its sacred text.