A Case Study of Local Markets in Delhi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

215 the History and Practice of Naming Streets in Delhi

International Journal of Advanced Research and Development International Journal of Advanced Research and Development ISSN: 2455-4030, Impact Factor: RJIF 5.24 www.advancedjournal.com Volume 2; Issue 3; May 2017; Page No. 215-218 The history and practice of naming streets in Delhi Nidhi M.A (F), Delhi School of Economics, Delhi, India Introduction: History of Streets which naming streets took place have changed considerably. The word ‘Street’ was borrowed from Latin language. The Delhi, India’s capital is believed to be one of the oldest cities Roman strata or paved roads were taken up to drive the word of the world. From Indraprastha to New Delhi, it had been a street. The word street helps us to recognise the roman roads long journey. As popularly believed, Delhi has been the site which were straight as an arrow, connecting the strategic for seven historic cities- Lalkot, Siri, Tughlaqabad, Jahan positions in the region. Panah, Ferozabad, Purana Quila and Shahajahanabad. The early forms of street transport were horses or even Shahajahanabad remains a living city till present housing humans carrying goods over tracks. The first improved trails about half a million people. would have been at mountain passes and through swamps. As 2.5.1 Street names of Shahajahanabad: Mughal Capital trade increased, the tracks were often flattened or widened to The seventh city of Delhi, Shahajahanabad was built in 1638 accommodate human and animal traffic, Some of these soil on the banks of river Yamuna. The two major streets of tracks were developed into broad networks, allowing Shahajahanabad were Chandni Chowk and Faiz Bazaar. -

DISTRICT MAGISTRATE .- Sh

LIST OF SPECIAL BLOs APPOINTED IN EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS FOR FACILITATING STUDENTS ENROLLMENT Sl. No. ASSEMBLY Name of College/Educational Name of special BLO and Telephone No./ CONSTITUENCIES Institute/School designation Mobile No. No. & NAME DISTRICT NORTH-EAST, NAME OF THE DISTRICT ELECTION OFFICER (DEO) /DISTRICT MAGISTRATE .- Sh. L. R. Garg, 22122732, Mob:8800995555,[email protected] 1. 63 (SEELAMPUR) SBV B-Block, Nand Nagri, Delhi. Sh. Budeshwar Pd Kunjan, principal 9911594980 22575804 2. 63 (SEELAMPUR) GSKV E-Block, Nand Nagri, Delhi Mrs. Asha Kumar (Vice Principal) 0120-2631169 22594460 3. 63 (SEELAMPUR) GGSSS C-Block, Dilshad Garden, Delhi. Mrs. Sunita Rahi, VicePrincipal 9810140041 22578191 4. 63 (SEELAMPUR) Flora Dale, Sr. Secondary Public Mrs. Indu Bhatia, Principal 22129159 School, R-PKT, Dilshad Garden. Delhi. 9560764705 5. 63 (SEELAMPUR) GGSSS janta Flats, GTB Enclave, Delhi. Mrs. Sushma Sharma, Vice Principal 9968827327 22574030 6. 63 (SEELAMPUR) GBSSS Between A & C Block, New Sh. L.R.Bharti, Principal 9891662477 Seemapuri, Delhi. 22353202 7. 63 (SEELAMPUR) ITI, Nand Nagri, Delhi Sh. Juwel Kujur, Principal 22134850 8. 64 (ROHTAS GBSS School, East of Loni Road Sh. C.P Singh, Principal 22817384 NAGAR) Shahdara Delhi-93 9. 64 (ROHTAS GGSS School, East of Loni Road Smt. B. Barla, Principal 22815660 NAGAR) Shahdara Delhi-93 10. 64 (ROHTAS GBSSS No.2, M.S. Park Shahdara Delhi Sh. Kiran Singh, Principal 22588428/ NAGAR) 9868490197 11. 64 (ROHTAS GBSSS No.1, M.S. Park Shahdara Delhi Sh. Ravi Dutt, Principal 22578531 NAGAR) 9910746125 12. 64 (ROHTAS GBSS School, Shivaji Park Shahdara Sh. Kishori Lal, Principal 22328736 NAGAR) Delhi 13. -

Case Study Vikas Marg, New Delhi Laxmi Nagar Chungi to Karkari Mor

Equitable Road Space : Case study Vikas Marg, New Delhi Laxmi Nagar Chungi to Karkari Mor PWD, Govt. of NCT of Delhi Methodology Adopted STAGE 1 : Understand Equitable Road Space and Design STAGE 2 : Study of different Guidelines. STAGE 3 : Identification of Case Study Location and Data Collection STAGE 4 : Data Analysis STAGE 5 : Design Considerations Need for Equitable Road Space Benefits of Equitable Design Increase in comfort of pedestrians Comfortable last mile connectivity from MRTS Stations – therefore increased ridership of Buses and Metro. Reduced dependency on the car, if shorter trips can be made comfortably by foot. Prioritization of public transport and non- motorized private modes in street design. Reduced car use leading to reduced congestion and pollution. More equity in the provision of comfortable public spaces and amenities to all sections Source: Street Design Guidelines © UTTIPEC, DDA 2009 of society. Guidelines of UTTIPEC for Equitable Road Space GOALS FOR “INTEGRATED” STREETS FOR DELHI: GOAL 1: • MOBILITY AND ACCCESSIBILITY – Maximum number of people should be able to move fast, safely and conveniently through the city. GOAL 2: • SAFETY AND COMFORT – Make streets safe clean and walkable, create climate sensitive design. GOAL 3: • ECOLOGY – Reduce impact on the natural environment; and Reduce pressure on built infrastructure. Mobility Goals: To ensure preferable public transport use: 1. To Retrofit Streets for equal or higher priority for Public Transit and Pedestrians. 2. Provide transit-oriented mixed land use patterns and redensify city within 10 minutes walk of MRTS stops. 3. Provide dedicated lanes for HOVs (high occupancy vehicles) and carpool during peak hours. Safety, Comfort Goals: 4. -

NDMC Ward No. 001 S

NDMC Ward No. 001 S. No. Ward Name of Name of Name of Enumeratio Extent of the Population Enumeration Total SC % of SC Name & town/Census District & Tahsil & n Block No. Block Population Population Population Code Town/ Village Code Code 0001 NDMC 7003 New Delhi 05 Connaught 0021(1) Devi Prasad Sadan 1-64, NDMC Flats 4 Place 001 Type-6, Asha Deep Apartment 9 Hailey 1 Road 44 Flats 656 487 74.24 0001 NDMC 7003 New Delhi 05 Connaught 0029 Sangli Mess Cluster (Slum) 2 Place 001 351 174 49.57 0001 NDMC 7003 New Delhi 05 Connaught 0031(2) Feroz Shah Road, Canning Lane Kerala 3 Place 001 School 593 212 35.75 0001 NDMC 7003 New Delhi 05 Connaught 0032(1) Princess Park Residential Area Copper 4 Place 001 Nicus Marg to Tilak Marg, 100 Houses 276 154 55.8 0001 NDMC 7003 New Delhi 05 Connaught 0032(2) Princess Park Residential Area Copper 5 Place 001 Nicus Marg to Tilak Marg, 105 Houses 312 142 45.51 0001 NDMC 7003 New Delhi 05 Connaught 0036(1) NSCI Club Cluster-171 Houses 6 Place 001 521 226 43.38 NDMC Ward No. 002 Ward Name of Name of Name of Enumeratio Extent of the Population Enumeration Total SC % of SC Name & town/Census District & Tahsil & n Block No. Block Population Population Population S. No. Code Town/ Village Code Code Parliament A1 to H18 CN 1 to 10 Palika Dham Bhai Vir 0002 NDMC 7003 New Delhi 05 0005-1 933 826 88.53 1 Street 003 Singh Marg Block 5 Jain Mandir Marg ,Vidhya Bhawan Parliament 0002 NDMC 7003 New Delhi 05 0009 ,Union Acadmy Colony 70 A -81 H Arya 585 208 35.56 Street 003 2 School Lane Parliament 1-126 Mandir Marg R.K. -

Seagate Crystal Reports Activex

PESHI REGISTER Peshi Register From 01-08-2015 To 31-08-2015 Book No. 1 No. S.No Reg.No. IstParty IIndParty Type of Deed Address Value Stamp Book No. Paid Laxmi Nagar 15143 -- MONIKA ASHA BAGRI SALE , SALE WITHIN MC Laxmi Nagar , House No. 400,000.00 16,000.00 1 AREA N-45-A/E ,Road No. , Mustail No. , Khasra , Area1 8, Area2 0, Area3 0 Laxmi Nagar Laxmi Nagar 25274 -- NEELAM TYAGI USHA RANI SALE , SALE WITHIN MC Laxmi Nagar , House No. 105 4,600,000.00 184,000.00 1 SHARMA AREA ,Road No. , Mustail No. , Khasra , Area1 63, Area2 0, Area3 0 Laxmi Nagar Laxmi Nagar 35357 -- MUJIB REHMAN BHAGWAN LAL SALE , SALE WITHIN MC Laxmi Nagar , House No. 9/320 5,100,000.00 238,007.00 1 AREA ,Road No. , Mustail No. , Khasra , Area1 80, Area2 0, Area3 0 Laxmi Nagar Laxmi Nagar 45392 -- SHEEL RAJ RANI DUBEY SALE , SALE WITHIN MC Laxmi Nagar , House No. 5 2,500,000.00 100,000.00 1 CHHABRA AREA ,Road No. , Mustail No. , Khasra , Area1 84, Area2 0, Area3 0 Laxmi Nagar Laxmi Nagar 55535 -- KANIZ BEGUM MUNAWWAR SALE , SALE WITHIN MC Laxmi Nagar , House No. 104 730,000.00 43,800.00 1 IQBAL AREA ,Road No. , Mustail No. , Khasra , Area1 11, Area2 0, Area3 0 Laxmi Nagar Laxmi Nagar 65632 -- CHANDRA GAURAV GARG SALE , SALE WITHIN MC Laxmi Nagar , House No. 110/2 5,700,000.00 285,000.00 1 BHATT AREA ,Road No. , Mustail No. , Khasra , ATTORNEY OF Area1 84, Area2 0, Area3 SAROJ KUMARI 0 Laxmi Nagar TYAGI 1 of 141 03 September 2015 PESHI REGISTER Peshi Register From 01-08-2015 To 31-08-2015 Book No. -

Delhi Tourism & Transportation Development Corporation Ltd

Delhi Tourism & Transportation Development Corporation Ltd. 18-A DDA SCO Complex, Defence Colony, New Delhi – 110 024 Telephone: 24618026, 24647005,24622364 Fax: 24697352 No.:DTTDC/Finance/Phy. Verification/2021/ . Date: . …… March 2021 Date of Physical verification : 1st April 2021 DUTY ALLOCATION S.N Name of Vend (IMFL & CL) Name of Officer Designation Place of posting deputed S/Sh. 1 Alipur Rajneesh Maan Jr. Asstt. DH PP Alipur CL Rajneesh Maan Jr. Asstt. DH PP 2 Ashok Vihar Deep Cinema Complex Azad Singh Store-Keeper GT Karnal Rd Vend 3 Azadpur (Naniwala Bagh) Naresh Arora Salesman Model Town-II IMFL Azadpur CL (Amber Tower) Naresh Arora Salesman Model Town-II IMFL 4 Badarpur Border Desh Raj Sr E. T. GFS 5 Bawana Road Neel Chand Manager II DH INA 6 Bawana Sector 5 Satish Kumar Bill Clerk Swaroop Nagar 7 Bhikaji Cama Place Mohan Ram Salesman II Safdarjung Enclave 8 Budh Vihar (A – 36) Kanjhawala Ranjeet Singh Sr. Life Guard Sanjay Gandhi Tpt IMFL 9 Budh Vihar (A-4) Pramod Rai DM Liquor Budh Vihar CL (A-4) Pramod Rai DM Liquor 10 Chand Bagh Mukesh kumar Salesman Meet Ngr vend 11 Chander Nagar Arvind Kumar Salesman HQs 12 Coffee Home Laxmi Ngr. IMFL Anil Kumar AM(IT) Liq Divn LN office 13 Darya Ganj Maniksha Bakshi DM(IT) HQs 14 DBG Road (Shop No. 138) Surinder Kumar Sr Cook Coffee Home CP 15 DBG Road IMFL (Shop No. 82 & 68) Surinder Kumar Sr Cook Coffee Home CP DBG Road CL (Shop No. 82 & 68) Surinder Kumar Sr Cook Coffee Home CP 16 Deenpur Dhani Ram Jr. -

AFES 2021 Program As of 7 June 2021 Page 1 of 4

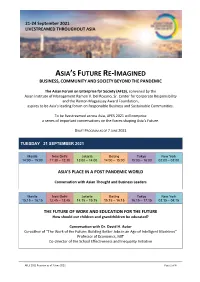

21-24 September 2021 LIVESTREAMED THROUGHOUT ASIA ASIA’S FUTURE RE-IMAGINED BUSINESS, COMMUNITY AND SOCIETY BEYOND THE PANDEMIC The Asian Forum on Enterprise for Society (AFES), convened by the Asian Institute of Management Ramon V. Del Rosario, Sr. Center for Corporate Responsibility and the Ramon Magsaysay Award Foundation, aspires to be Asia’s leading forum on Responsible Business and Sustainable Communities. To be livestreamed across Asia, AFES 2021 will comprise a series of important conversations on the forces shaping Asia’s Future. DRAFT PROGRAM AS OF 7 JUNE 2021 TUESDAY 21 SEPTEMBER 2021 Manila New Delhi Jakarta Beijing Tokyo New York 14:00 – 15:00 11:30 – 12:30 13:00 – 14:00 14:00 – 15:00 15:00 – 16:00 02:00 – 03:00 ASIA’S PLACE IN A POST PANDEMIC WORLD Conversation with Asian Thought and Business Leaders Manila New Delhi Jakarta Beijing Tokyo New York 15:15 – 16:15 12:45 – 13:45 14:15 – 15:15 15:15 – 16:15 16:15 – 17:15 03:15 – 04:15 THE FUTURE OF WORK AND EDUCATION FOR THE FUTURE How should our children and grandchildren be educated? Conversation with Dr. David H. Autor Co-author of “The Work of the Future: Building Better Jobs in an Age of Intelligent Machines” Professor of Economics, MIT Co-director of the School Effectiveness and Inequality Initiative AFES 2021 Program as of 7 June 2021 Page 1 of 4 21-24 September 2021 LIVESTREAMED THROUGHOUT ASIA TUESDAY 21 SEPTEMBER 2021 Manila New Delhi Jakarta Beijing Tokyo New York 16:30 – 17:45 14:00 – 15:15 15:30 – 16:45 16:30 – 17:45 17:30 – 18:45 04:30 – 05:45 TECHNOLOGY, INNOVATION AND COMMUNITY The Acceleration of Digitalization and AI will bring extraordinary efficiency gains but also much greater inequality. -

807A Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

807A bus time schedule & line map 807A Old Delhi Railway Station (Fatehpuri) View In Website Mode The 807A bus line (Old Delhi Railway Station (Fatehpuri)) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Old Delhi Railway Station (Fatehpuri): 6:10 AM - 7:50 PM (2) Uttam Nagar Terminal: 6:50 AM - 9:30 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 807A bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 807A bus arriving. Direction: Old Delhi Railway Station (Fatehpuri) 807A bus Time Schedule 54 stops Old Delhi Railway Station (Fatehpuri) Route VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Timetable: Sunday 6:10 AM - 7:50 PM Uttam Nagar Terminal Monday 6:10 AM - 7:50 PM Uttam Nagar / A1 Janak Puri Tuesday 6:10 AM - 7:50 PM Tilak Pul Wednesday 6:10 AM - 7:50 PM Thursday 6:10 AM - 7:50 PM Jivan Park Friday 6:10 AM - 7:50 PM C-1 Janak Puri Saturday 6:10 AM - 7:50 PM A-3 Janak Puri C-2 Janakpuri 807A bus Info C2b Janak Puri Direction: Old Delhi Railway Station (Fatehpuri) Stops: 54 C4e Janakpuri Trip Duration: 78 min Line Summary: Uttam Nagar Terminal, Uttam Nagar C-3 Janakpuri / A1 Janak Puri, Tilak Pul, Jivan Park, C-1 Janak Puri, A-3 Janak Puri, C-2 Janakpuri, C2b Janak Puri, C4e C-4h Janakpuri Janakpuri, C-3 Janakpuri, C-4h Janakpuri, Janakpuri C-5a, Desu Colony, Sagarpur Vashisht Park, D Block Janakpuri C-5a Janak Puri, Lajwanti Garden, Zunk Market, Gulab House, Bobby Soap, Ps Mayapuri, Metal Forging, Desu Colony Government Press, Mayapuri Depot, Naraina Vihar / Indra Market, Payal Cinema, Loha Mandi, Bentax, Sagarpur Vashisht Park Naraina Depot, Pandav -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and w h itephotographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing the World'sUMI Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8824569 The architecture of Firuz Shah Tughluq McKibben, William Jeffrey, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by McKibben, William Jeflfrey. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. -

1 DELHI TRAFFIC POLICE TRAFFIC ADVISORY Traffic Arrangements

DELHI TRAFFIC POLICE TRAFFIC ADVISORY Traffic Arrangements – Republic Day Celebrations on 26Th January, 2021 Republic Day will be held on 26th January, 2021. The Parade will start at 9.50 AM from Vijay Chowk and proceed to National Stadium, whereas Tableaux will start from Vijay Chowk and proceed to Red Fort Ground . There will be wreath laying function at National War Memorial at 09.00 AM. There would be elaborate traffic arrangements and restrictions in place for smooth conduct of the Parade and Tableaux along the respective routes. ROUTE OF THE PARADE/TABLEAUX :- (A) Parade Route:- Vijay Chowk- Rajpath- Amar Jawan Jyoti- India Gate- R/A Princess Palace-T/L Tilak Marg Radial Road- Turn right on “C” Hexagon- Turn left and enter National Stadium from Gate No. 1. (B) Tableaux Route :- Vijay Chowk- Rajpath- Amar Jawan Jyoti- India Gate- R/A Princess Palace-T/L Tilak Marg - Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg – Netaji Subhash Marg - Red Fort. TRAFFIC RESTRICTIONS In order to facilitate smooth passage of the Parade, movement of traffic on certain roads leading to the route of the Parade and Tableaux will be restricted as under:- (1). No traffic will be allowed on Vijay Chowk from 06.00 PM on 25.01.2021 till Parade is over. Rajpath is already out of bounds. (2). No cross traffic on Rajpath intersections from 11.00 PM on 25.01.2021 at Rafi Marg, Janpath, Man Singh Road till Parade is over. (3). ‘C’-Hexagon-India Gate will be closed for traffic from 05.00 AM on 26.01.2021 till Tableaux crosses Tilak Marg. -

Police Station for Dmrc Metro Network in Ncr

POLICE STATION FOR DMRC METRO NETWORK IN NCR DELHI POLICE (METRO) Spl. CP Transport/Training 8130099002 Jt CP/Transport 011-23490245 9818099039 DCP (Metro) 011-23222114 8130099090 Police Station office Mobile Metro Police Control Room SHPK Police Control for DMRP 1511, 011-221839030, 11-22183904 8800294695 North OFFICE/ Police Station Mobile ACP. METRO (North) 011-23925500, 011-26501231 9718450002 SHO RI 011-27058384, 011-27058283 9958097236 SHO KG 011-23923015, 011-23923016 8750871323 SHO SHKP 011-22173623(DO), 011-22173624 8750871322 SHO RG 011-25150008(DO), 011-25150002 8750871327 SHO RCK 011-23279036,38 9868896452 SHO AZU 011-27428025, 011-27428025 9818542888 SHO NNOI 011-25962200 8750871321 SHO NSHP 011-27312827, 011-27312826 9968003125 South OFFICE/ Police Station Mobile ACP. METRO (South) 011-26501321 8750871208 SHO IGA 7290007616 8750871326 9810470765 SHO YB 011-22486281(DO), 011-22483660 8750871328 8800294695 SHO PTDM 011-22486281(DO) 9810270796 SHO NP 011-26984547 8750871325 9654203965 SHO INA 011-26880100, 011-26880200 7011902856 SHO OVM 011-26984548 8750871324 9811711786 SHO GTNI 011-26501325 9268111170 SHO JP 8800294693 9999659947 GURGOAN POLICE OFFICE/ Police Station Mobile Email CP GURUGRAM 2311200, 2312200 [email protected] DCP.EAST & Metro 0124-2573659, 2573659 9999981804 [email protected] ACP HQ/Taffic & Metro 0124-2577185 9999981814 [email protected] ACP DLF 0124-2577057 9999981813 [email protected] SHO METRO IFFCO 0124-2570800 9999981829 [email protected] FARIDABAD POLICE OFFICE/ Police Station Mobile -

CONCRETE PRODUCTS DIVISION (Gurugram-Haryana) P R O D U C T S INDEX

CONCRETE PRODUCTS DIVISION (Gurugram-Haryana) P r o d u c t s INDEX • About CPD • Detailed Product Description – Engineered Concrete Blocks – Pavers – Kerb Stones – Readymix Concrete • Contact Us ABOUT CPD Sobha Concrete Products represent Quality & Detail in every Block with State of the Art Technology, World Class Imported Machinery and Sobha’s stringent quality standards. Since inception, Sobha Concrete Products has always strived for benchmark quality, customer-centric approach, robust engineering, in-house research, uncompromising business ethics, timeless values and transparency in all spheres of business conduct, which have contributed in making Sobha a preferred real estate brand in India. A ‘BIG PICTURE’ approach to Building Performance! Engineered Concrete Blocks With Sobha Engineered concrete blocks, it is not that hard to make a strong quality statement. Because, at Sobha we make sure that every single concrete block is crafted to perfection using state-of-the-art technology and imported machinery from REIT Engineered concrete solid block Engineered concrete cellular/hollow block Engineered Concrete Solid Blocks Typical usage for concrete block - Foundation walls - typically rock faced. - Basement walls. - Partition walls - usually plain faced. - Exterior walls - usually plain faced and then often covered with stucco. - Most concrete block was used as a back-up material or for cavity wall construction. Engineered Concrete Solid Blocks ADVANTAGES • Weather Resistance: Very low water absorbing quality and they offer stronger resistance to water leakage and also withstand adverse weather conditions. • Saving Raw Material: Up to 60% reduction in cement mortar consumption (Compare to conventional bricks). It saves on time of labor, raw material and result in more rapidly construction.