Historical Virtues of the Walnut Andrew F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Invented Herbal Tradition.Pdf

Journal of Ethnopharmacology 247 (2020) 112254 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Ethnopharmacology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jethpharm Inventing a herbal tradition: The complex roots of the current popularity of T Epilobium angustifolium in Eastern Europe Renata Sõukanda, Giulia Mattaliaa, Valeria Kolosovaa,b, Nataliya Stryametsa, Julia Prakofjewaa, Olga Belichenkoa, Natalia Kuznetsovaa,b, Sabrina Minuzzia, Liisi Keedusc, Baiba Prūsed, ∗ Andra Simanovad, Aleksandra Ippolitovae, Raivo Kallef,g, a Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, Via Torino 155, 30172, Mestre, Venice, Italy b Institute for Linguistic Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences, Tuchkov pereulok 9, 199004, St Petersburg, Russia c Tallinn University, Narva rd 25, 10120, Tallinn, Estonia d Institute for Environmental Solutions, "Lidlauks”, Priekuļu parish, LV-4126, Priekuļu county, Latvia e A.M. Gorky Institute of World Literature of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 25a Povarskaya st, 121069, Moscow, Russia f Kuldvillane OÜ, Umbusi village, Põltsamaa parish, Jõgeva county, 48026, Estonia g University of Gastronomic Sciences, Piazza Vittorio Emanuele 9, 12042, Pollenzo, Bra, Cn, Italy ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Ethnopharmacological relevance: Currently various scientific and popular sources provide a wide spectrum of Epilobium angustifolium ethnopharmacological information on many plants, yet the sources of that information, as well as the in- Ancient herbals formation itself, are often not clear, potentially resulting in the erroneous use of plants among lay people or even Eastern Europe in official medicine. Our field studies in seven countries on the Eastern edge of Europe have revealed anunusual source interpretation increase in the medicinal use of Epilobium angustifolium L., especially in Estonia, where the majority of uses were Ethnopharmacology specifically related to “men's problems”. -

OXHEART TOMATO & GREEN JUNIPER Components

RECIPE GARUM OXHEART TOMATO & GREEN JUNIPER Components Grilled strawberries Red oxalis Veal head Pickled maple blossom Marmande D‘Antan tomatoes (8-10 cm Ø) Green juniper powder Tomato gelée Garum sauce Tomato/raspberry gel Lovage oil GRILLED MARMANDE TOMATO STRAWBER- D‘ANTAN GELÉE RIES TOMATOES Grill the red strawberries (not too Blanch and peel the tomatoes. 220 g clear tomato stock* sweet) and cut them into 3 mm Carefully cut them into 28 g slices 1,6 g Agar cubes, spread them out and chill so that the slices retain the shape 0,6 g Gelatine immediately. of the tomatoes. Place the slices 0,4 g of citrus next to each other on a deep Tomami (hearty) baking tray and cover with green White balsamic vinegar juniper oil heated to 100°C, leave to stand for at least 6 hours. Flavor the tomato stock* with tomami, vinegar, salt and sugar. Then bind with texturizers and pour on a plastic tray. Afterwards cut out circles with a ring (9 cm Ø). *(mix 1 kg of tomatoes with salt, put in a kitchen towel and place over a container to drain = stock) CHAUSSEESTRASSE 8 D-10115 BERLIN MITTE TEL. +49 30.24 62 87 60 MAIL: [email protected] TOMATO/ GARUM TROUT RASPBERRY SAUCE GARUM GEL 100 ml tomato stock* 1 L poultry stock from heavily 1 part trout (without head, fins 15 g fresh raspberries roasted poultry carcasses. and offal) Pork pancreas Sea salt Flavored with 20 g Kombu (5 % of trout weight) algae for for 30 minutes. Water (80 % of trout Mix everything together and 55 g Sauerkraut (with bacon) weight) Sea salt (10 % of strain through a fine sieve. -

HUNTIA a Journal of Botanical History

HUNTIA A Journal of Botanical History VOLUME 16 NUMBER 2 2018 Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh The Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation, a research division of Carnegie Mellon University, specializes in the history of botany and all aspects of plant science and serves the international scientific community through research and documentation. To this end, the Institute acquires and maintains authoritative collections of books, plant images, manuscripts, portraits and data files, and provides publications and other modes of information service. The Institute meets the reference needs of botanists, biologists, historians, conservationists, librarians, bibliographers and the public at large, especially those concerned with any aspect of the North American flora. Huntia publishes articles on all aspects of the history of botany, including exploration, art, literature, biography, iconography and bibliography. The journal is published irregularly in one or more numbers per volume of approximately 200 pages by the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation. External contributions to Huntia are welcomed. Page charges have been eliminated. All manuscripts are subject to external peer review. Before submitting manuscripts for consideration, please review the “Guidelines for Contributors” on our Web site. Direct editorial correspondence to the Editor. Send books for announcement or review to the Book Reviews and Announcements Editor. All issues are available as PDFs on our Web site. Hunt Institute Associates may elect to receive Huntia as a benefit of membership; contact the Institute for more information. Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation Carnegie Mellon University 5th Floor, Hunt Library 4909 Frew Street Pittsburgh, PA 15213-3890 Telephone: 412-268-2434 Email: [email protected] Web site: http://www.huntbotanical.org Editor and layout Scarlett T. -

200 Bc - Ad 400)

ARAM, 13-14 (2001-2002), 171-191 P. ARNAUD 171 BEIRUT: COMMERCE AND TRADE (200 BC - AD 400) PASCAL ARNAUD We know little of Beirut's commerce and trade, and shall probably continue to know little about this matter, despite a lecture given by Mrs Nada Kellas in 19961. In fact, the history of Commerce and Trade relies mainly on both ar- chaeological and epigraphical evidence. As far as archaeological evidence is concerned, one must remember that only artefacts strongly linked with ceram- ics, i.e. vases themselves and any items, carried in amphoras, (predominantly, but not solely, liquids, can give information about the geographical origin, date and nature of such products. The huge quantities of materials brought to the light by recent excavations in Beirut should, one day, provide us with new evi- dence about importations of such products in Beirut, but we will await the complete study of this material, which, until today by no means provided glo- bal statistics valid at the whole town scale. The evidence already published still allows nothing more than mere subjective impressions about the origins of the material. I shall try nevertheless to rely on such impressions about that ma- terial, given that we lack statistics, and that it is impossible to infer from any isolated sherd the existence of permanent trade-routes and commercial flows. The results of such an inquiry would be, at present, worth little if not con- fronted with other evidence. On the other hand, it should be of great interest to identify specific Berytan productions among the finds from other sites in order to map the diffusion area of items produced in Beirut and the surrounding territory. -

Dioscorides De Materia Medica Pdf

Dioscorides de materia medica pdf Continue Herbal written in Greek Discorides in the first century This article is about the book Dioscorides. For body medical knowledge, see Materia Medica. De materia medica Cover of an early printed version of De materia medica. Lyon, 1554AuthorPediaus Dioscorides Strange plants RomeSubjectMedicinal, DrugsPublication date50-70 (50-70)Pages5 volumesTextDe materia medica in Wikisource De materia medica (Latin name for Greek work Περὶ ὕλης ἰατρικῆς, Peri hul's iatrik's, both means about medical material) is a pharmacopeia of medicinal plants and medicines that can be obtained from them. The five-volume work was written between 50 and 70 CE by Pedanius Dioscorides, a Greek physician in the Roman army. It was widely read for more than 1,500 years until it supplanted the revised herbs during the Renaissance, making it one of the longest of all natural history books. The paper describes many drugs that are known to be effective, including aconite, aloe, coloxinth, colocum, genban, opium and squirt. In all, about 600 plants are covered, along with some animals and minerals, and about 1000 medicines of them. De materia medica was distributed as illustrated manuscripts, copied by hand, in Greek, Latin and Arabic throughout the media period. From the sixteenth century, the text of the Dioscopide was translated into Italian, German, Spanish and French, and in 1655 into English. It formed the basis of herbs in these languages by such people as Leonhart Fuchs, Valery Cordus, Lobelius, Rembert Dodoens, Carolus Klusius, John Gerard and William Turner. Gradually these herbs included more and more direct observations, complementing and eventually displacing the classic text. -

"You Can't Make a Monkey out of Us": Galen and Genetics Versus Darwin

"You can't make a monkey out of us": Galen and genetics versus Darwin Diamandopoulos A. and Goudas P. Summary The views on the biological relationship between human and ape are polarized. O n e end is summarized by the axiom that "mon is the third chimpanzee", a thesis put forward in an indirect way initially by Charles Darwin in the 19 th century.The other is a very modern concept that although similar, the human and ape genomes are distinctly different. We have compared these t w o views on the subject w i t h the stance of the ancient medical w r i t e r Galen.There is a striking resemblance between current and ancient opinion on three key issues. Firstly, on the fact that man and apes are similar but not identical. Secondly, on the influence of such debates on fields much wider than biology.And finally, on the comparative usefulness of apes as a substitute for human anatomy and physiology studies. Resume Les points de vue concernant les liens biologiques existants entre etre humain et singe sont polarises selon une seule direction. A I'extreme, on pourrait resumer ce point de vue par I'axiome selon lequel « I'homme est le troisieme chimpanze ». Cette these fut indirectement soutenue par Charles Darwin, au I9eme siecle. L'autre point de vue est un concept tres moderne soutenant la similitude mais non I'identite entre les genomes de I'homme et du singe. Nous avons compare ces deux points de vue sur le sujet en mentionnant celui du medecin ecrivain Galien, dans I'Antiquite. -

Prehľad Dejín Biológie, Lekárstva a Farmácie

VYSOKOŠKOLSKÁ UČEBNICA UNIVERZITA PAVLA JOZEFA ŠAFÁRIKA V KOŠICIACH PRÍRODOVEDECKÁ FAKULTA Katedra botaniky Prehľad dejín biológie, lekárstva a farmácie Martin Bačkor a Miriam Bačkorová Košice 2018 PREHĽAD DEJÍN BIOLÓGIE, LEKÁRSTVA A FARMÁCIE Vysokoškolská učebica Prírodovedeckej fakulty UPJŠ v Košiciach Autori: 2018 © prof. RNDr. Martin Bačkor, DrSc. Katedra botaniky, Prírodovedecká fakulta, UPJŠ v Košiciach 2018 © RNDr. Miriam Bačkorová, PhD. Katedra farmakognózie a botaniky, UVLF v Košiciach Recenzenti: doc. RNDr. Roman Alberty, CSc. Katedra biológie a ekológie, Fakulta prírodných vied, UMB v Banskej Bystrici doc. MVDr. Tatiana Kimáková. PhD. Ústav verejného zdravotníctva, Lekárska fakulta, UPJŠ v Košiciach Vedecký redaktor: prof. RNDr. Beňadik Šmajda, CSc. Katedra fyziológie živočíchov, Prírodovedecká fakulta, UPJŠ v Košiciach Technický editor: Mgr. Margaréta Marcinčinová Všetky práva vyhradené. Toto dielo ani jeho žiadnu časť nemožno reprodukovať, ukladať do in- formačných systémov alebo inak rozširovať bez súhlasu majiteľov práv. Za odbornú a jazykovú stránku tejto publikácie zodpovedajú autori. Rukopis neprešiel redakčnou ani jazykovou úpravou Tento text vznikol aj vďaka materiálnej pomoci z projektu KEGA 012UPJŠ-4/2016. Vydavateľ: Univerzita Pavla Jozefa Šafárika v Košiciach Dostupné od: 22. 10. 2018 ISBN 978-80-8152-650-3 OBSAH PREDHOVOR ................................................. 5 1 STAROVEK ................................................ 6 1.1 Zrod civilizácie ........................................................8 -

Romans Had So Many Gods

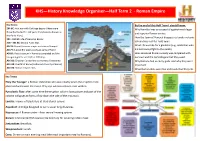

KHS—History Knowledge Organiser—Half Term 2 - Roman Empire Key Dates: By the end of this Half Term I should know: 264 BC: First war with Carthage begins (There were Why Hannibal was so successful against much lager three that lasted for 118 years; they become known as and superior Roman armies. the Punic Wars). How the town of Pompeii disappeared under volcanic 254 - 191 BC: Life of Hannibal Barker. ash and was lost for 1500 years. 218—201 BC: Second Punic War. AD 79: Mount Vesuvius erupts and covers Pompeii. What life was like for a gladiator (e.g. celebrities who AD 79: A great fire wipes out huge parts of Rome. did not always fight to the death). AD 80: The colosseum in Rome is completed and the How advanced Roman society was compared with inaugural games are held for 100 days. our own and the technologies that they used. AD 312: Emperor Constantine converts to Christianity. Why Romans had so many gods. And why they were AD 410: The fall of Rome (Goths sack the city of Rome). important. AD 476: Roman empire ends. What Roman diets were like and foods that they ate. Key Terms Pliny the Younger: a Roman statesman who was nearby when the eruption took place and witnessed the event. Only eye witness account ever written. Pyroclastic flow: after some time the eruption column loses power and part of the column collapses to form a flow down the side of the mountain. Lanista: Trainer of Gladiators at Gladiatorial school. Aqueduct: A bridge designed to carry water long distances. -

The Monumental Villa at Palazzi Di Casignana and the Roman Elite in Calabria (Italy) During the Fourth Century AD

The Monumental Villa at Palazzi di Casignana and the Roman Elite in Calabria (Italy) during the Fourth Century AD. by Maria Gabriella Bruni A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classical Archaeology in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Committee in Charge Professor Christopher H. Hallett, Chair Professor Ronald S. Stroud Professor Anthony W. Bulloch Professor Carlos F. Noreña Fall 2009 The Monumental Villa at Palazzi di Casignana and the Roman Elite in Calabria (Italy) during the Fourth Century AD. Copyright 2009 Maria Gabriella Bruni Dedication To my parents, Ken and my children. i AKNOWLEDGMENTS I am extremely grateful to my advisor Professor Christopher H. Hallett and to the other members of my dissertation committee. Their excellent guidance and encouragement during the major developments of this dissertation, and the whole course of my graduate studies, were crucial and precious. I am also thankful to the Superintendence of the Archaeological Treasures of Reggio Calabria for granting me access to the site of the Villa at Palazzi di Casignana and its archaeological archives. A heartfelt thank you to the Superintendent of Locri Claudio Sabbione and to Eleonora Grillo who have introduced me to the villa and guided me through its marvelous structures. Lastly, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my husband Ken, my sister Sonia, Michael Maldonado, my children, my family and friends. Their love and support were essential during my graduate -

Halligan's Love Affair with Food

Coolabah, No.5, 2011, ISSN 1988-5946, Observatori: Centre d’Estudis Australians, Australian Studies Centre, Universitat de Barcelona Halligan’s Love Affair with Food Anne Holden Rønning Copyright©2011 Anne Holden Rønning. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged. Abstract: Marion Halligan’s non-fiction Eat My Words, (1990), Cockles of the Heart (1996) and The Taste of Memory (2004) all have food as their main topic. Travelling round Europe on culinary journeys and staying in hotels and flats she provides us, as readers, with a wealth of recipes and reflections on the role food plays in people’s lives, socially and culturally. This article will discuss some few of the points Halligan raises as she comments on the pleasure of food; on bricolage, both in the finished product and in cookery books; and the language we use to describe food and its processes. Adopting a bicultural approach Halligan compares Australian foods of today with those of her childhood, thus turning these food books into a kind of autobiography. Keywords: food; pleasure; bricolage and cookery books; naming. In Eat My Words Marion Halligan cites Alexis Soyer in his 1853 book The Pantropheon as being “fond of saying that people only eat to live when they don’t know how to live to eat,” thus underscoring the importance of food culturally and historically. To these words Halligan adds: “Chefs, whose livelihood is other’s eating, know that the best food begins in the mind” (209). -

Poulton Hall Has Been in the Family for Many Upper Field, Past a Monument Erected by Scirard De Generations

Issue No. 28 October 2010 Newsletter Patron: The Viscount Ashbrook Company Limited by Guarantee, no. 05673816 www.cheshire-gardens-trust.org.uk Charity Number 1119592 Inside: Some future events: Trentham Gardens Mrs Delany and her Circle – Sat. 17h November Gardening the British way in Iraq 19th century Villa Gardens – Sat. 22nd January Harvington Hall Gresgarth Hall – February (date t.b.c.) Gardens on the Isle of Wight Roswitha Arnold on German gardens: Spring What to do with your apple harvest Lecture at end of March (date t.b.c.) PPoouullttoonn HHaallll Without doubt this is the quirkiest garden that we Launcelyn built his castle on a defensive mound above have visited. the river Dibbin. Full of humour and literary associations, it is a A later house was probably destroyed by fire; the memorial to Roger Lancelyn-Green, the biographer second house, built in the seventeenth century, was and writer of children‟s fiction, and has been designed brick built with stone coigns and is just recognizable. by his wife, June Lancelyn-Green, to reflect his It was later stuccoed but when this deteriorated it was interests and his books. pebble-dashed. From the car park the Hall is approached through the Poulton Hall has been in the family for many Upper Field, past a monument erected by Scirard de generations. In the eleventh century Scirard de Launcelyn, and over a Ha-ha. 2 The lawns at the front of the house have always been It is, in fact, a series of gardens, each with a literary a major feature and were much admired by Nathanial theme. -

![Salmagundy [ 1723 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2806/salmagundy-1723-2602806.webp)

Salmagundy [ 1723 ]

SALMAGUNDY [ 1723 ] iven the medieval suspicion of raw Library (Sloane ms 1201) has an alphabetical ingredients, and the taste for flesh list of more than a hundred herbs to be found and spectacle (which brought swan, in a well-stocked garden, from Alexanders and peacock and porpoise to the dining anise to verbena and wormseed. table), you might assume there was little interest From this wealth of plant life, mixed herb in salad in the Middle Ages. But this is not the and flower salads were created that proved case; there’s a recipe for Salat in the earliest extremely popular throughout the Middle Ages extant cookbook in English, The Forme of Cury, and beyond. The inclusion of edible flowers which was compiled around 1390 (see page 19): provided the drama of colour that medieval TO MAK E A S ALAMONGUNDY, diners took such delight in. And, since they S ALMINGONDIN, OR S ALGUNDY Take persel, sawge, grene garlic, chibolles, were thought to have medicinal properties, oynouns, leek, borage, myntes, porrettes, fenel, salad leaves escaped the stigma attached to and toun cressis, rew, rosemarye, purslarye; many raw fruits and vegetables (though not Mince a couple of Chickens, either boil’d or roasted very fine or Veal, if you lave and waische hem clene. Pike hem. Pluk everyone agreed: in the Boke of Kervynge, please; also mince the Yolks of hard Eggs very small; and mince also the Whites hem small with thyn honde and myng hem written around 1500, Wynkyn de Worde wel with rawe oile; lay on vunegar and salt, warned: “beware of grene sallettes & raw fruytes of the Eggs very small by themselves; also shred the Pulp of Lemons very small; and serve it forth.