Criticism in Quintilian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brutus, Cassius, Judas, and Cremutius Cordus: How

BRUTUS, CASSIUS, JUDAS, AND CREMUTIUS CORDUS: HOW SHIFTING PRECEDENTS ALLOWED THE LEX MAIESTATIS TO GROUP WRITERS WITH TRAITORS by Hunter Myers A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford, Mississippi May 2018 Approved by ______________________________ Advisor: Professor Molly Pasco-Pranger ______________________________ Reader: Professor John Lobur ______________________________ Reader: Professor Steven Skultety © 2018 Hunter Ross Myers ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Dr. Pasco-Pranger, For your wise advice and helpful guidance through the thesis process Dr. Lobur & Dr. Skultety, For your time reading my work My parents, Robin Myers and Tracy Myers For your calm nature and encouragement Sally-McDonnell Barksdale Honors College For an incredible undergraduate academic experience iii ABSTRACT In either 103 or 100 B.C., a concept known as Maiestas minuta populi Romani (diminution of the majesty of the Roman people) is invented by Saturninus to accompany charges of perduellio (treason). Just over a century later, this same law is used by Tiberius to criminalize behavior and speech that he found disrespectful. This thesis offers an answer to the question as to how the maiestas law evolved during the late republic and early empire to present the threat that it did to Tiberius’ political enemies. First, the application of Roman precedent in regards to judicial decisions will be examined, as it plays a guiding role in the transformation of the law. Next, I will discuss how the law was invented in the late republic, and increasingly used for autocratic purposes. The bulk of the thesis will focus on maiestas proceedings in Tacitus’ Annales, in which a total of ten men lose their lives. -

Stasis-Theory in Homeric Commentary

This is a repository copy of Stasis-theory in Homeric commentary . White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/390/ Article: Heath, M. (1993) Stasis-theory in Homeric commentary. Mnemosyne, 46 (3). pp. 356-363. ISSN 0026-7074 Reuse See Attached Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Mnemosyne 46 (1993), 356-63 St£sij-theory in Homeric commentary Malcolm Heath University of Leeds ABSTRACT: (i) Analysis of the small number of references to the rhetorical theory of stasis (issue-theory) in the Homeric scholia shows that they assume a modified version of the theory of Athenaeus, a contemporary and rival of Hermagoras of Temnos. (ii) In his discussion of Agamemnon's speech in Iliad 3.456-60 Eustathius follows the discussion in Plutarch Quaestiones convivales 9.13, rather than that in the scholia. It is shown that this is justified on technical grounds. The interpretation in the scholia does not fit Agamemnon's speech, and must have originated in a discussion of the attested Homeric 'problem' concerning claims that the Trojans had broken their oath. I The sporadic references to st£sij-theory in the scholia to the Iliad employ an unusual terminology.1 The following terms are found: (A1) parormhtik» (9.228; 23.594); (A2) katastocastik» (18.497-8); (A3) ¢lloiwtik» (1.118; 8.424; 9.228, 312-3), of which tÕ ØpallaktikÒn is a part (9.228); (A4) dikaiologik» (23.594);2 (A5) ·htÕn kaˆ di£noia (3.457). -

“At the Sight of the City Utterly Perishing Amidst the Flames Scipio Burst Into

Aurelii are one of the three major Human subgroups within western Eramus, and the founders of the mighty (some say “Eternal”) “At the sight of the city utterly perishing Aurelian Empire. They are a sturdy, amidst the flames Scipio burst into tears, conservative group, prone to religious fervor and stood long reflecting on the inevitable and philosophical revelry in equal measure. change which awaits cities, nations, and Adding to this a taste for conquest, and is it dynasties, one and all, as it does every one any wonder the Aurelii spread their of us men. This, he thought, had befallen influence, like a mighty eagle spreading its Ilium, once a powerful city, and the once wings, across the known world? mighty empires of the Assyrians, Medes, Persians, and that of Macedonia lately so splendid. And unintentionally or purposely he quoted---the words perhaps escaping him Aurelii stand a head shorter than most unconsciously--- other humans, but their tightly packed "The day shall be when holy Troy shall forms hold enough muscle for a man twice fall their height. Their physical endurance is And Priam, lord of spears, and Priam's legendary amongst human and elf alike. folk." Only the Brutum are said to be hardier, And on my asking him boldly (for I had and even then most would place money on been his tutor) what he meant by these the immovable Aurelian. words, he did not name Rome distinctly, but Skin color among the Aurelii is quite was evidently fearing for her, from this sight fluid, running from pale to various shades of the mutability of human affairs. -

Roman Literature from Its Earliest Period to the Augustan Age

The Project Gutenberg EBook of History of Roman Literature from its Earliest Period to the Augustan Age. Volume I by John Dunlop This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: History of Roman Literature from its Earliest Period to the Augustan Age. Volume I Author: John Dunlop Release Date: April 1, 2011 [Ebook 35750] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HISTORY OF ROMAN LITERATURE FROM ITS EARLIEST PERIOD TO THE AUGUSTAN AGE. VOLUME I*** HISTORY OF ROMAN LITERATURE, FROM ITS EARLIEST PERIOD TO THE AUGUSTAN AGE. IN TWO VOLUMES. BY John Dunlop, AUTHOR OF THE HISTORY OF FICTION. ivHistory of Roman Literature from its Earliest Period to the Augustan Age. Volume I FROM THE LAST LONDON EDITION. VOL. I. PUBLISHED BY E. LITTELL, CHESTNUT STREET, PHILADELPHIA. G. & C. CARVILL, BROADWAY, NEW YORK. 1827 James Kay, Jun. Printer, S. E. Corner of Race & Sixth Streets, Philadelphia. Contents. Preface . ix Etruria . 11 Livius Andronicus . 49 Cneius Nævius . 55 Ennius . 63 Plautus . 108 Cæcilius . 202 Afranius . 204 Luscius Lavinius . 206 Trabea . 209 Terence . 211 Pacuvius . 256 Attius . 262 Satire . 286 Lucilius . 294 Titus Lucretius Carus . 311 Caius Valerius Catullus . 340 Valerius Ædituus . 411 Laberius . 418 Publius Syrus . 423 Index . 453 Transcriber's note . 457 [iii] PREFACE. There are few subjects on which a greater number of laborious volumes have been compiled, than the History and Antiquities of ROME. -

Medieval Canon Law and Early Modern Treaty Law Lesaffer, R.C.H

Tilburg University Medieval canon law and early modern treaty law Lesaffer, R.C.H. Published in: Journal of the History of International Law Publication date: 2000 Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Lesaffer, R. C. H. (2000). Medieval canon law and early modern treaty law. Journal of the History of International Law, 2(2), 178-198. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. sep. 2021 178 Journal of the History of International Law The Medieval Canon Law of Contract and Early Modern Treaty Law Randall Lesaffer Professor of Legal History, Catholic University of Brabant at Tilburg; Catholic University of Leuven The earliest agreements between political entities which can be considered to be treaties date back from the third millennium B.C1. Throughout history treaties have continuously been a prime instrument of organising relations between autonomous powers. -

Handout Name Yourself Like a Roman (CLAS 160)

NAME YOURSELF LIKE A ROMAN Choose Your Gender 0 Roman naming conventions differed for men and women, and the Romans didn’t conceive of other options or categories (at least for naming purposes!). For viri (men): Choose Your Praenomen (“first name”) 1 This is your personal name, just like modern American first names: Michael, Jonathan, Jason, etc. The Romans used a very limited number of first names and tended to be very conservative about them, reusing the same small number of names within families. In the Roman Republic, your major options are: Some of these names (Quintus, Sextus, • Appius • Manius • Servius Septimus, etc.) clearly originally referred • Aulus • Marcus • Sextus to birth order: Fifth, Sixth, Seventh. Others are related to important aspects of • Decimus • Numerius • Spurius Roman culture: the name Marcus probably • Gaius • Postumus • Statius comes from the god Mars and Tiberius from the river Tiber. Other are mysterious. • Gnaeus • Publius • Tiberius But over time, these names lost their • Lucius • Quintus • Titus original significance and became hereditary, with sons named after their • Mamercus • Septimus • Vibius father or another male relative. Choose Your Nomen (“family name”) 2 Your second name identifies you by gens: family or clan, much like our modern American last name. While praenomina vary between members of the same family, the nomen is consistent. Some famous nomina include Claudius, Cornelius, Fabius, Flavius, Julius, Junius, and Valerius. Side note: if an enslaved person was freed or a foreigner was granted citizenship, they were technically adopted into the family of their “patron,” and so received his nomen as well. De Boer 2020 OPTIONAL: Choose Your Cognomen (“nickname”) Many Romans had just a praenomen and a nomen, and it was customary and polite to address a 3 person by this combo (as in “hello, Marcus Tullius, how are you today?” “I am well, Gaius Julius, and you?”). -

Historical Jesus a Contemporary Roman Perspective

Historical Jesus A Contemporary Roman Perspective Jason Janich NewLife906.com 1. Thallus 55 A.D. Thallus was a Greek Historian around 55A.D. who wrote a three volume account of the Eastern Mediterranean area. Although his works have been lost, fragments of it exist in the citations of others. As quoted by Julius Africansus (160 A.D -240 A.D.) On the whole world there pressed a most fearful darkness; and the rocks were rent by an earthquake, and many places in Judea and other districts were thrown down. This darkness Thallus, in the third book of his History, calls as appears to me without a reason, an eclipse of the sun. (Donaldson, A. R. (1973). Julius Africanus, Exant Writings, XVIII in the Ante- Nicene Fathers, ed Vol. VI. Grand RApids: Eerdmans.) What can we establish from Thallus’ writing? - The Christian Gospel was known in the Mediterranean by the middle of the first century – this is around AD 52, probably prior to the writing of the gospels. - There was a widespread darkness in the land, implied to have taken place during Jesus’ crucifixion. - Unbelievers offered rationalistic explanations for certain Christian teachings. 1 | P a g e 2. Pliny the Younger (61 A.D. – 113 A.D.) Letters 10.96-97 Pliny was the Governor of Bithynia in Asia Minor and is a noted historian with at least 10 volumes. In one letter he writes to the Emperor Trajan seeking counsel as to how to treat Christians. In the case of those who were denounced to me as Christians, I have observed the following procedure: I interrogated these as to whether they were Christians; those who confessed I interrogated a second and a third time, threatening them with punishment; those who persisted I ordered executed. -

Tao of Seneca: Volume 2

VOLUME 2 VOLUME 2 The Tao of Seneca, Volume 2 Based on the Moral Letters to Lucilius by Seneca, translated by Richard Mott Gummere. Loeb Classical Library® edition Volume 1 first published 1917; Volume 2 first published in 1920; Volume 3 first published 1925. Loeb Classical Library is a registered trademark of The President and Fellows of Harvard College. Front Cover Design by FivestarBranding™ (www.fivestarlogo.com) Book Interior Design and Typography by Laurie Griffin (www.lauriegriffindesign.com) Printed in U.S.A. THESE VOLUMES ARE DEDICATED TO ALL WHO SEEK TO BETTER THEMSELVES AND, IN DOING SO, BETTER THE WORLD. —Tim Ferriss TABLE OF CONTENTS LETTER 66 On Various Aspects of Virtue 9 LETTER 67 On Ill-Health and Endurance of Suffering 25 THOUGHTS FROM MODERN STOICS: Massimo Pigliucci 30 LETTER 68 On Wisdom and Retirement 36 LETTER 69 On Rest and Restlessness 41 LETTER 70 On the Proper Time to Slip the Cable 43 LETTER 71 On the Supreme Good 52 LETTER 72 On Business as the Enemy of Philosophy 64 LETTER 73 On Philosophers and Kings 69 LETTER 74 On Virtue as a Refuge From Worldly Distractions 74 LETTER 75 On the Diseases of the Soul 86 LETTER 76 On Learning Wisdom in Old Age 93 LETTER 77 On Taking One’s Own Life 104 LETTER 78 On the Healing Power of the Mind 111 LETTER 79 On the Rewards of Scientific Discovery 120 LETTER 80 On Worldly Deceptions 127 LETTER 81 On Benefits 131 LETTER 82 On the Natural Fear of Death 142 LETTER 83 On Drunkenness 152 THOUGHTS FROM MODERN STOICS: William B. -

Rhetoric in European Culture and Beyond

Prof. PhDr. Jiří Kraus, DrSc. Rhetoric in European and World Culture traces the position of rhetoric in cultural Cover image: Allegory of Rhetoric. (1935) and educational systems from ancient times to the present. Here, Jiří Kraus examines František Václav Adámek ( 1713–1779), Professor Kraus lectures at the Faculty of Social Sciences, rhetoric’s decline in importance during a period of rationalism and enlightenment, from the Matthias Bernard Braun school. Charles University in Prague. Between 1963–2002 he worked presents the causes of negative connotations of rhetoric, and explains why rhetoric Rhetoric in European Chateau park in Lysá nad Labem, near Prague. in the Czech Language Institute of the Academy of Sciences, in the twentieth century regained its prestige. Kraus demonstrates that the reputation where he pursued mathematical linguistics prior to changing of rhetoric falls when it is reduced to a refined method for deceiving the public and his focus onto language culture and rhetoric. He is a member increases when it is seen as a scientific discipline throughout the humanities. In this Culture and Beyond of the editorial boards of prominent Czech linguistic journals sense, the author argues, rhetoric strives for universal recognition and the cultivation and of Charles University’s science council. After the cold of rhetorical expression, spoken and written, including not only its production but also war era, he became a member of the International Society for reception and interpretation. the History of Rhetoric, striking personal relations with leading Apart from classical and medieval rhetoric the book presents the condensed history world representatives in the field, particularly with Professor of rhetoric in France, Spain, Italy, Germany, England and Scotland as well as in the C. -

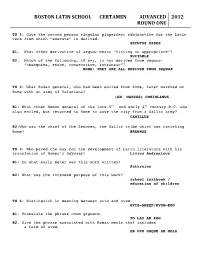

2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the Second Person Singular Pluperfect Subjunctive for the Latin Verb from Which “Execute” Is Derived

BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the second person singular pluperfect subjunctive for the Latin verb from which “execute” is derived. SECUTUS ESSES B1. What other derivative of sequor means “fitting or appropriate”? SUITABLE B2. Which of the following, if any, is not derived from sequor: “obsequies, ensue, consecutive, intrinsic”? NONE: THEY ARE ALL DERIVED FROM SEQUOR TU 2: What Roman general, who had been exiled from Rome, later marched on Rome with an army of Volscians? (GN. MARCUS) CORIOLANUS B1: What other Roman general of the late 5th and early 4th century B.C. was also exiled, but returned to Rome to save the city from a Gallic army? CAMILLUS B2:Who was the chief of the Senones, the Gallic tribe which was ravishing Rome? BRENNUS TU 3: Who paved the way for the development of Latin literature with his translation of Homer’s Odyssey? Livius Andronicus B1: In what early meter was this work written? Saturnian B2: What was the intended purpose of this work? school textbook / education of children TU 4: Distinguish in meaning between ovis and ovum. OVIS—SHEEP/OVUM—EGG B1. Translate the phrase ovum gignere. TO LAY AN EGG B2. Give the phrase associated with Roman meals that includes a form of ovum. AB OVO USQUE AD MALA BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012&& ROUND&ONE,&page&2&&&! TU 5: Who am I? The Romans referred to me as Catamitus. My father was given a pair of fine mares in exchange for me. According to tradition, it was my abduction that was one the foremost causes of Juno’s hatred of the Trojans? Ganymede B1: In what form did Zeus abduct Ganymede? eagle/whirlwind B2: Hera was angered because the Trojan prince replaced her daughter as cupbearer to the gods. -

Expulsion from the Senate of the Roman Republic, C.319–50 BC

Ex senatu eiecti sunt: Expulsion from the Senate of the Roman Republic, c.319–50 BC Lee Christopher MOORE University College London (UCL) PhD, 2013 1 Declaration I, Lee Christopher MOORE, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Thesis abstract One of the major duties performed by the censors of the Roman Republic was that of the lectio senatus, the enrolment of the Senate. As part of this process they were able to expel from that body anyone whom they deemed unequal to the honour of continued membership. Those expelled were termed ‘praeteriti’. While various aspects of this important and at-times controversial process have attracted scholarly attention, a detailed survey has never been attempted. The work is divided into two major parts. Part I comprises four chapters relating to various aspects of the lectio. Chapter 1 sees a close analysis of the term ‘praeteritus’, shedding fresh light on senatorial demographics and turnover – primarily a demonstration of the correctness of the (minority) view that as early as the third century the quaestorship conveyed automatic membership of the Senate to those who held it. It was not a Sullan innovation. In Ch.2 we calculate that during the period under investigation, c.350 members were expelled. When factoring for life expectancy, this translates to a significant mean lifetime risk of expulsion: c.10%. Also, that mean risk was front-loaded, with praetorians and consulars significantly less likely to be expelled than subpraetorian members. -

Magic and the Roman Emperors

1 MAGIC AND THE ROMAN EMPERORS (1 Volume) Submitted by Georgios Andrikopoulos, to the University of Exeter as a thesis/dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics, July 2009. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. ..................................... (signature) 2 Abstract Roman emperors, the details of their lives and reigns, their triumphs and failures and their representation in our sources are all subjects which have never failed to attract scholarly attention. Therefore, in view of the resurgence of scholarly interest in ancient magic in the last few decades, it is curious that there is to date no comprehensive treatment of the subject of the frequent connection of many Roman emperors with magicians and magical practices in ancient literature. The aim of the present study is to explore the association of Roman emperors with magic and magicians, as presented in our sources. This study explores the twofold nature of this association, namely whether certain emperors are represented as magicians themselves and employers of magicians or whether they are represented as victims and persecutors of magic; furthermore, it attempts to explore the implications of such associations in respect of the nature and the motivations of our sources. The case studies of emperors are limited to the period from the establishment of the Principate up to the end of the Severan dynasty, culminating in the short reign of Elagabalus.