Aberystwyth University Religion and the Fabrication of Race

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unit-3 Vedic Society 3.0 Objectives

Unit-3 Vedic Society Index 3.0 Objectives 3.1 Introduction 3.2 Presentation of Subject Matter 3.2.1 Section I: Original Home of Vedic Aryans, Vedic Literature 3.2.2 Section II: Early Vedic period 3.2.3 Section III: Later Vedic period 3.2.4 Section IV: Position of Women 3.3 Summary 3.4. Terms to Remember 3.5 Answers to check your progress 3.6 Exercise 3.7 Reference for Further Study 3.0 Objectives From this unit, we can understand, G The Vedic people and debates regarding their original home G Two parts of Vedic period and reasons behind periodization G Life in Early Vedic Period G Life in Later Vedic Period G Position of Women in Vedic Period 71 3.1 Introduction In Unit -2, we studied India's development from Prehistory to Protohistory, We studied that India went through the processes of first Urbanization in Harappan period. However, mostly due to the environmental reasons, the affluent Harappan civilization and its architectural prosperity faced a gradual decline. After the decline of Harappan civilization, we find references of a certain kind of culture in the area of Saptasindhu region. Who were those and what was their culture is the matter of this Unit. 3.2 Presentation of Subject Matter 3.2.1 Section I: The Aryans and their Original Home a. Who were the Aryans? Near about 1500 BC, we find a new culture in the Saptasindhu region, which was of nomadic nature. They were pastoralists who used to speak a different language, i.e. -

The Role of Hindu Women in Preserving Intangible Cultural Heritage in Mauritius

Journal of Foreign Languages, Cultures and Civilizations December 2018, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 17-26 ISSN 2333-5882 (Print) 2333-5890 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/jflcc.v6n2a3 URL: https://doi.org/10.15640/jflcc.v6n2a3 The Role of Hindu Women in Preserving Intangible Cultural Heritage in Mauritius Mrs Rashila Vigneshwari Ramchurn1 Abstract This paper elucidates the depth of Hindu women‟s contribution in preserving intangible cultural heritage in Mauritius. Intangible cultural heritage means the practices, expressions, knowledge, skills, instruments, objects, arte facts and cultural spaces which are recognised by communities, groups and individuals. Globalisation has changed lifestyle and causing threat to intangible cultural heritage. This is an ethnographical research where participants observation, interviewing by engaging in daily life of people and recording life histories methods have been done within a period of one year. Thirty people above sixty years were interviewed both males and females. The interviews were done in creole and then transcribed to English. Oral narratives are still at its infancy in Mauritius and it is worthy to research as there is no academic research done on this topic. Three visits were paid to each participant to get acquainted with them and get their trust. Their ways of living were observed. Secondary data such as newspapers and books have been used. A diary was kept to know moods, special emotions and local expression of language of the respondents. This paper will lay emphasis on women as tradition bearers. It is both a qualitative research 1.1 Introduction Gender has often determined the type of working material according to local tradition. -

Ancient Civilizations Huge Infl Uence

India the rich ethnic mix, and changing allegiances have also had a • Ancient Civilizations huge infl uence. Furthermore, while peoples from Central Asia • The Early Historical Period brought a range of textile designs and modes of dress with them, the strongest tradition (as in practically every traditional soci- • The Gupta Period ety), for women as well as men, is the draping and wrapping of • The Arrival of Islam cloth, for uncut, unstitched fabric is considered pure, sacred, and powerful. • The Mughal Empire • Colonial Period ANCIENT CIVILIZATIONS • Regional Dress Harappan statues, which have been dated to approximately 3000 b.c.e. , depict the garments worn by the most ancient Indi- • The Modern Period ans. A priestlike bearded man is shown wearing a togalike robe that leaves the right shoulder and arm bare; on his forearm is an armlet, and on his head is a coronet with a central circular decora- ndia extends from the high Himalayas in the northeast to tion. Th e robe appears to be printed or, more likely, embroidered I the Karakoram and Hindu Kush ranges in the northwest. Th e or appliquéd in a trefoil pattern. Th e trefoil motifs have holes at major rivers—the Indus, Ganges, and Yamuna—spring from the the centers of the three circles, suggesting that stone or colored high, snowy mountains, which were, for the area’s ancient inhab- faience may have been embedded there. Harappan female fi gures itants, the home of the gods and of purity, and where the great are scantily clad. A naked female with heavy bangles on one arm, sages meditated. -

Judaism: a Supplemental Resource for Grade 12 World of Religions: A

Change and Evolution Stages in the Development of Judaism: A Historical Perspective As the timeline chart presented earlier demonstrates, the development of the Jewish faith and tradition which occurred over thousands of years was affected by a number of developments and events that took place over that period. As with other faiths, the scriptures or oral historical records of the development of the religion may not be supported by the contemporary archaeological, historical, or scientific theories and available data or artifacts. The historical development of the Jewish religion and beliefs is subject to debate between archeologists, historians, and biblical scholars. Scholars have developed ideas and theories about the development of Jewish history and religion. The reason for this diversity of opinion and perspectives is rooted in the lack of historical materials, and the illusive nature, ambiguity, and ambivalence of the relevant data. Generally, there is limited information about Jewish history before the time of King David (1010–970 BCE) and almost no reliable biblical evidence regarding what religious beliefs and behaviour were before those reflected in the Torah. As the Torah was only finalized in the early Persian period (late 6th–5th centuries BCE), the evidence of the Torah is most relevant to early Second Temple Judaism. As well, the Judaism reflected in the Torah would seem to be generally similar to that later practiced by the Sadducees and Samaritans. By drawing on archeological information and the analysis of Jewish Scriptures, scholars have developed theories about the origins and development of Judaism. Over time, there have been many different views regarding the key periods of the development of Judaism. -

Nanakian Philosophy ( Gurmat )

Nanakian Philosophy ( Gurmat ) The Path of Enlightenment by Baldev Singh, Ph.D. 2035 Tres Picos Drive, Yuba City, CA 95993, USA E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: 530-870-8040 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Chapter 1: Guru Nanak & the Indian Society Chapter 2: The Nanakian Philosophy Introduction Theology/Religion 1. God 2. Guru and Sikh 3. Purpose of Life 4. Soul 5. Salvation 6. Divine Benevolence Cosmology 1. Cosmos and Evolution 2. Hukam 3. Ecology/Environmental Harmony Cause of Human Progress and Suffering Maya and Haumai Repudiation of Old Dogmas 1. Karma and Reincarnation 2. Hell and Heaven Universal Equality and Human Values 1. Moral and Social Responsibility 2. Ethics a. Knowledge b. Truthful Living c. Compassion d. Love e. Humility and Forgiveness 3. Exaltation of Woman a. Role of Women in the Sikh Revolution 4. Message of Universal Humanism Justice and Peace 1. Just Rule 2. Babur Bani Establishment of Sikh Panth Punjabi Language and Literature Conclusion Introduction Guru Nanak’s advent (1469-1539) is an epoch-making singular event in the recorded history. His unique, revolutionary and liberating philosophy of universal humanism –liberty, love, respect, justice and equality, is applicable for all. Sikhs and non-Sikhs alike have written abundantly about him, on his philosophy in Punjabi, English and some other languages. Regrettably, most if not all, is addressed in a superficial, superfluous and contradictory manner; so much so that some authors in the spirit of ignorance even exercised repudiation of Nanak’s precious thoughts which are enshrined in the Aad Guru Granth Sahib (Sikh Scripture), the only authentic source of the Nanakian philosophy ( Gurma t). -

Heart-Hinduism

P art 3: H o w t o t e a c h a b o ut Hi n d ui s m, Getti n g t o t he Heart of Hi n d uis m: A Co mprehensive Guide for R E Teachers 1 4 p a g e s fr o m t h e 8 0 p a g e ori gi n al I N S E T G ui d e Specially produced for Hertfordshire Pri mary Teachers for a Conference on 7th October 2009 Part 3: H o w t o Teac h a bout Hinduis m Br o a d G ui d eli n e s T e a c hi n g I d e a s P u pil s W or k s h e et s F or fr e e a d vi c e a n d i nf or m ati o n o n t e m pl e s vi sit s, g u e st s p e a k er s a n d I N S E T, pl e a s e d o c o nt a ct: I S K C O N E d u c ati o n al S er vi c e s, B h a kti v e d a nt a M a n or, Hilfi el d L a n e, Al d e n h a m, W atf or d, H ert s., W D 2 5 8 E Z, U. -

Indian Costumes

A. BISWAS t PUBLICATIONS DIVISION Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 with funding from Public.Resource.Org https://archive.org/details/indiancostumesOObisw . * <* INDIAN COSTUMES A. BISWAS PUBLICATIONS DIVISION MINISTRY OF INFORMATION AND BROADCASTING GOVERNMENT OF INDIA First print : 1985 (Saka 1906) Reprint: 2003 (Saka 1924) © Publications Division ISBN : 81-230-1055-9 Price : Rs. 110.00 Published by The Director, Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, Patiala House, New Delhi-110 001 SALES EMPORIA • PUBLICATIONS DIVISION • Patiala House, Tilak Marg, New Delhi-110001 (Ph. 23387069) • Soochna Bhavan, CGO Complex, Lodhi Road, New Delhi-110003 (Ph. 24367260) • Hall No. 196, Old Secretariat, Delhi-110054 (Ph. 23890205) • Commerce House, Currimbhoy Road, Ballard Pier, Mumbai-400038 (Ph. 22610081) • 8, Esplanade East, Kolkata-700069 (Ph. 22488030) • Rajaji Bhawan, Besant Nagar, Chennai-600090 (Ph. 24917673) • Press Road, Near Govt. Press, Thiruvananthapuram-695001 (Ph. 2330650) • Block No. 4,1st Floor, Gruhakalpa Complex, M.G. Road, Nampally, Hyderabad-500001 (Ph. 24605383) • 1st Floor, /F/ Wing, Kendriya Sadan, Koramangala, Bangalore-560034 (Ph. 25537244) • Bihar State Co-operative Bank Building, Ashoka Rajpath, Patna-800004 (Ph. 22300096) ® 2nd floor, Hall No 1, Kendriya Bhawan, Aliganj, Lucknow - 226 024 (Ph. 2208004) • Ambica Complex, 1st Floor, Paldi, Ahmedabad-380007 (Ph. 26588669) • Naujan Road, Ujan Bazar, Guwahati-781001 (Ph. 2516792) SALES COUNTERS • PRESS INFORMATION BUREAU • CGO Complex, 'A' Wing, A.B. Road, Indore (M.P.) (Ph. 2494193) • 80, Malviya Nagar, Bhopal-462003 (M.P.) (Ph. 2556350) • B-7/B, Bhawani Singh Road, Jaipur-302001 (Rajasthan) (Ph. 2384483) Website : http://www.publicationsdivision.nic.in E-mail : [email protected] or [email protected] Typeset at : Quick Prints, Naraina, New Delhi - 110 028. -

Windsor Conference 2016

Proceedings of 9th Windsor Conference: Making Comfort Relevant Cumberland Lodge, Windsor, UK, 7-10 April 2016. Network for Comfort and Energy Use in Buildings, http://nceub.org.uk Why is the Indian Sari an all-weather gear? Clothing insulation of Sari, Salwar- Kurti, Pancha, Lungi, and Dhoti Madhavi Indragant1 , Juyoun Lee2 , Hui Zhang3,4 and Edward A. Arens3,5 1 Department of Architecture & Urban Planning, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar (Communicating author) [email protected] 2 HAE R&D Center, LG Electronics, South Korea, [email protected] 3 Center for the Built Environment (CBE), University of California, Berkeley, CA 4 [email protected], 5 [email protected] Abstract Barring a few reports on the clothing insulation of sari and salwar-Kurti, little is known about the other traditional ensembles men use in South Asia and beyond. To accurately account for the thermal insulation on the human body, simulation studies necessitate insulation on various body parts. This study reports the segmental level insulation of 52 traditional ensembles of both genders recorded in a climate chamber. Indian garments are worn as ensembles. We focused on the drape, as traditional ensembles offer great opportunities for thermal adaptation through changing drape. We researched on 41 sari ensembles, four salwar-kurti and seven men’s’ ensembles, such as dhoti, pancha and lungi. More than the material, drape has a significant effect on the clothing insulation. For the same pieces of garments, the clo value of the ensemble varied by as much as 3.1 to 32 %, through changing drape in saris, the lower values being associated with lighter saris. -

Peirce Middle School's Student News Quarterly

Peirce Middle School’s Student News Quarterly P a g e 2 Summer 2017 Inside this issue: Cover Art by Nivi Anton Overcoming Our Fears by Althea Mae Hutchinson 3 Equal Rights, 2017 by Nolan Prochnau and Althea Mae Hutchinson 4 The Evolution of Science by Mithra Sarkari 5-6 Protons, Electrons, and their Charges by Althea Mae Hutchinson 7-8 A Bear’s Perspective on Henlopen by Meredith Young 9 The Dog Days: Keeping Dogs Safe by Elizabeth Brennan 10 Some Summer Reading Suggestions 11 Summer Fun on a Budget (Plus: Mini Vacations Close to Home) 12-13 Life Hacks for Students by Abheya Nair and Marcela Bernal 14 What are Shadow? By Althea Mae Hutchinson 15-16 Summer Recipes by Gabi Fernandes 17 America’s Treasures: Our National Parks by Elizabeth Brennan 18 The Not-so-Daily Doodle by Braden Lieberman 19- Summer Puzzle 20 By Althea Mae Hutchinson Worry is a weird thing, a thing we find ourselves worried about. We find ourselves worried, then grow concerned because we can’t identify the cause of our worry. We talk ourselves in circles, through worry, to concern, and past fear, and back again. We worry about nearly everything, and use the word interchangeably with fear. We wonder what people will think of us, about small things: if our hair looks okay, if our clothes are al- right. We worry about bigger things that affect our survival: if we have enough money, if we can truly trust our friends, if we will be accepted by the group. We fear judgement above all else. -

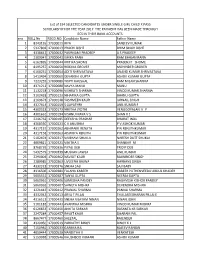

Sno ROLL No REGD.NO. Candidate Name Father Name 1 8243155 17000011 RIYA SANJEEV KUMAR 2 5327802 17000013 PRACHI BISHT BHIM SINGH

List of 194 SELECTED CANDIDATES UNDER SINGLE GIRL CHILD X PASS SCHOLARSHIP FOR THE YEAR 2017. THE PAYMENT HAS BEEN MADE THROUGH ECS IN THEIR BANK ACCOUNTS. sno ROLL No REGD.NO. Candidate Name Father Name 1 8243155 17000011 RIYA SANJEEV KUMAR 2 5327802 17000013 PRACHI BISHT BHIM SINGH BISHT 3 4338642 17000032 PAURNAMI PRADEEP A S PRADEEP 4 2309047 17000043 ISHIKA RANA RAM BHAJAN RANA 5 6163895 17000044 KRITIKA SHOME PRASENJIT SHOME 6 8195257 17000050 RIDDIKA GROVER MOHINDER GROVER 7 6168251 17000054 ADITI SHRIVASTAVA ANAND KUMAR SHRIVASTAVA 8 5413494 17000060 DEVANSHI GUPTA ASHOK KUMAR GUPTA 9 7223255 17000080 TRIPTI KAUSHAL RAM MILAN SHARMA 10 4371212 17000088 NAVYA MANU MANU 11 1132218 17000096 VISHRUTI SHARMA VINOD KUMAR SHARMA 12 5102428 17000123 NIHARIKA GUPTA BHANU GUPTA 13 2169673 17000148 YASHMEEN KAUR JARNAIL SINGH 14 4327414 17000159 S GAYATHRY ANIL KUMAR P 15 4300323 17000173 NIKITHA JYOTHI VENUGOPALAN K P 16 4301661 17000194 VISHNU MAYA V S SHAN V S 17 2246762 17000195 DEEKSHA PRASHAR BHARAT INDU 18 4368330 17000223 C V ANUSHKA P V ASHOK KUMAR 19 4317157 17000262 ABHIRAMI RENJITH P N RENJITHKUMAR 20 4317158 17000263 AISWRYA RENJITH P N RENJITHKUMAR 21 5102474 17000317 VAIBHAVI SHUKLA NARESH DUTT SHUKLA 22 4009821 17000321 VINITHA S SHANKAR M 23 8768739 17000336 PIYALI DEB TRIDIP DEB 24 5432579 17000339 MUSKAN JAWLA ANIL KUMAR 25 2290004 17000362 NAVJOT KAUR RAJWINDER SINGH 26 2289985 17000363 LIVLEENA BAJWA HARBANS SINGH 27 4332323 17000376 SNEHA SAJI SAJI BABY 28 4316506 17000381 FALAHA KABEER KABEER PUTHENVEEDU ABDUL KHADER -

ROCKY MOUNTIAN HEALTH PLANS DUALCARE PLUS Directory of Participating Physicians Providers & Dentists

ROCKY MOUNTIAN HEALTH PLANS DUALCARE PLUS Directory of Participating Physicians Providers & Dentists H2582_MC_DIR_PR80_01012021 SEP 2021 Notice of Nondiscrimination Rocky Mountain Health Plans (RMHP) complies with applicable Federal civil rights laws and does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, or sex. RMHP does not exclude people or treat them differently because of race, color, national origin, age, disability, sex, sexual orientation, or gender identity. RMHP takes reasonable steps to ensure meaningful access and effective communication is provided timely and free of charge: • Provides free auxiliary aids and services to people with disabilities to communicate effectively with us, such as: • Qualified sign language interpreters (remote interpreting service or on-site appearance) • Written information in other formats (large print, audio, accessible electronic formats, other formats) • Provides free language assistance services to people whose primary language is not English, such as: • Qualified interpreters (remote or on-site) • Information written in other languages If you need these services, contact the RMHP Member Concerns Coordinator at 800-346-4643, 970-243-7050, or TTY 970-248-5019, 800-704-6370, Relay 711; para asistencia en español llame al 800-346-4643. If you believe that RMHP has failed to provide these services or discriminated in another way on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, sex, sexual orientation, or gender identity, you can file a grievance with: the RMHP EEO Officer. You can file a grievance in person or by phone, mail, fax, or email. • Phone: 800-346-4643, 970-244-7760, ext. 7883, or TTY 970-248-5019, 800-704-6370, Relay 711; para asistencia en español llame al 800-346-4643 • Mail: ATTN: EEO Officer, Rocky Mountain Health Plans, PO Box 10600, Grand Junction, CO 81502-5600 • Fax: ATTN: EEO Officer, 970-244-7909 • Email: [email protected] If you need help filing a grievance, the RMHP EEO Officer is available to help you. -

Hinduism: a Supplemental Resource for Grade 12 World of Religions: a Canadian Perspective 59 Although Castes Were Not Initially Hereditary, They Eventually Became So

Practices, Rituals, Symbols, and Special Days/Celebrations Within Hindu devotion there are many practices and rituals. There are both everyday rites as well as rites to mark particularly important life events and passages, such as births, deaths, weddings, and so forth. Hindu practice aims towards the fulfillment of four central goals: kama (sensual pleasure, whether physical, psychological, or emotional), artha (virtuous material power and wealth), dharma (properly aligned conduct), and moksha (escape from the cycle of rebirth). Social Organization and Roles Hinduism, like many other faith groups, has social and cultural traditions, norms, and practices that have significant influence on the life of practitioners and the society in which they live. Many of these are not unique to Hinduism and some were the cause of social reform. The following are a few of these social practices and traditions. Caste System Figure 18: Seventy-Two Specimens of Castes in India 1837 Full book available from Historically, Indian and Hindu archive.org/details/seventytwospecimens1837 populations have been grouped along vocational lines into a caste system. The caste system divides Hindus into four main categories: Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Shudras. Many believe that these four castes originated from Brahma, the Hindu god of creation. The main castes were further divided into about 3,000 castes and 25,000 sub-castes, each based on their specific occupation. Outside of this Hindu caste system were the achhoots—the Dalits or the untouchables. Hinduism: A Supplemental Resource for Grade 12 World of Religions: A Canadian Perspective 59 Although castes were not initially hereditary, they eventually became so.