Reassessing English Alabaster Carving: Medieval Sculpture and Its

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ADBOU Skeletal List

Updated 17-03-2011 ADBOU Skeletal List Museum Place Type Year of Use of Number of Approx. number excavation cemetery graves comming- led bones ASR 1015 Ribe Grey Friar City Monastery 1993 1200-1560 915 City Cemetery 2008 1000-1700 113 373 ASR 13 Ribe Lindegården Vikings 2009 900-1000 10 7 ASR 1727 Ribe 1 FHM Aarhus Cathedral City Cemetery 1995-2002 1100-1800 197 3880/4330 FHM 3970 Nordby Rural Cemetery 1996 1050-1250 126 109 FHM 4461 Vestergade 3 City Cemetery 2003 18 FHM 4633 Aarhus Vor Frue City Cemetery 2005 43 Tvillum Rural Cemetery 2009 5 FHM 4985 Brattingborg, Samsø Rural Cemetery 2008 28 159 HAM 2843 Nybøl Rural Cemetery 1994 1100- 70 HAM 3702 Haderslev Cathedral City Cemetery 1998 -1800 20 HAM 5081 Haderslev Cathrdral City Cemetery 2010 -1800 17 HOM 1046 Sejet Rural Cemetery 2006 1150-1574 435 194 Monastery church, HOM 1272 City Cemetery 2007-2008 1600-1800 221 281 Horsens Ole Worms gade, HOM 1649 City Cemetery 2008-2009 1100-1500 578 686 Horsens JAH 1-77 Sct. Michael, Viborg City Cemetery 1979 1000-1529 285 215 JAH 2-79/ Viborg Cathedral Domkirke 1975-1981 1000-1800 120 1-81/2-80 JAH 2-84 Frederiksgade, Århus City Monastery 1984 1450-1560 22 JAH 3-80 Skt. Oluf, Århus City Cemetery 1981 -1700 90 a VKH 1201 Tirup/Bygholm Rural Cemetery 1984 1150-1350 574 46 VKH 1586 Vejle Klostergade City Cemetery 1985 1200 23 VSM 29F Faldborg Rural Cemetery 1994 1100-1600 80 VSM 804E/ 843C/806F/85 Sct. Mathias. Viborg City Cemetery 1994-1999 1100-1529 280 5F/906F VSM 902F Skt. -

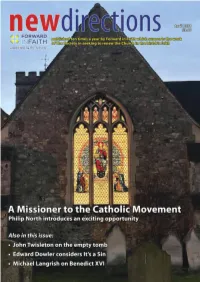

The Empty Tomb

content regulars Vol 24 No 299 April 2021 6 gHOSTLy cOunSEL 3 LEAD STORy 20 views, reviews & previews AnDy HAWES A Missioner to the catholic on the importance of the church Movement BOOkS: Christopher Smith on Philip North introduces this Wagner 14 LOST SuffOLk cHuRcHES Jack Allen on Disability in important role Medieval Christianity EDITORIAL 18 Benji Tyler on Being Yourself BISHOPS Of THE SOcIETy 35 4 We need to talk about Andy Hawes on Chroni - safeguarding cles from a Monastery A P RIEST 17 APRIL DIARy raises some important issues 27 In it from the start urifer emerges 5 The Empty Tomb ALAn THuRLOW in March’s New Directions 19 THE WAy WE LIvE nOW JOHn TWISLETOn cHRISTOPHER SMITH considers the Resurrection 29 An earthly story reflects on story and faith 7 The Journal of Record DEnIS DESERT explores the parable 25 BOOk Of THE MOnTH WILLIAM DAvAgE MIcHAEL LAngRISH writes for New Directions 29 Psachal Joy, Reveal Today on Benedict XVI An Easter Hymn 8 It’s a Sin 33 fAITH Of OuR fATHERS EDWARD DOWLER 30 Poor fred…Really? ARTHuR MIDDLETOn reviews the important series Ann gEORgE on Dogma, Devotion and Life travels with her brother 9 from the Archives 34 TOucHIng PLAcE We look back over 300 editions of 31 England’s Saint Holy Trinity, Bosbury Herefordshire New Directions JOHn gAyfORD 12 Learning to Ride Bicycles at champions Edward the Confessor Pusey House 35 The fulham Holy Week JAck nIcHOLSOn festival writes from Oxford 20 Still no exhibitions OWEn HIggS looks at mission E R The East End of St Mary's E G V Willesden (Photo by Fr A O Christopher Phillips SSC) M I C Easter Chicks knitted by the outreach team at Articles are published in New Directions because they are thought likely to be of interest to St Saviour's Eastbourne, they will be distributed to readers. -

Report Template

Committee: Date: Board of Governors of the Guildhall School 23 July 2018 of Music & Drama Subject: Principal’s Public Report Public Report of: The Principal For Information 1. Quality of learning and teaching environment The School has been rated Gold in the recent Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF3). This is testament to the commitment of all of our staff, both academic and administrative, who have worked extremely hard continuously to improve elements of our teaching and learning environment. In its statement about awarding Guildhall its highest possible rating, the Office for Students, noted that ‘continuation rates are consistent with the provider’s benchmark, that progression to highly skilled employment or further study is outstanding and that student satisfaction with academic support is exceptionally high and above the provider’s benchmark.’ The TEF panel noted the high contact hours and intensive one-to-one tuition Guildhall students receive, the personalised nature of learning, strong student representation and engagement, and outstanding physical and digital resources, as well as Guildhall’s strategic commitment to attracting students from diverse backgrounds. This award came in the same week that Guildhall was ranked as the UK’s top conservatoire in the Guardian’s University Guide 2019 for Music, and third among all UK higher education institutions for Music. We have now received confirmation of the success of our PIP bid to the City Corporation for £150K to support a new initiative within Production Arts. Our Multimedia Business Unit - Video Projection Mapping proposal was well received by the recent Resource and Allocation Sub Committee on July 5. The School continues to have critical success in the area of video mapping and live events and this funding will allow us to build on this success and transform our ability to offer more professional opportunities to students in these expanding areas of industry practice. -

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and The

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and the Margins of English Gothic Architecture MATTHEW M. REEVE For Eric Fernie This paper considers the sculpted capitals in Wells cathedral. Although integral to the early Gothic fabric, they have hitherto eluded close examination as either a component of the building or as an important cycle of ecclesiastical imagery in their own right. Consideration of the archaeological evidence suggests that the capitals were introduced mid-way through the building campaigns and were likely the products of the cathedral’s masons rather than part of an original scheme for the cathedral as a whole. Possible sources for the images are considered. The distribution of the capitals in lay and clerical spaces of the cathedral leads to discussion of how the imagery might have been meaningful to diCerent audiences on either side of the choir screen. introduction THE capital sculpture of Wells Cathedral has the dubious honour of being one of the most frequently published but least studied image cycles in English medieval art. The capitals of the nave, transepts, and north porch of the early Gothic church are ornamented with a rich array of figural sculptures ranging from hybrid human-animals, dragons, and Old Testament prophets, to representations of the trades that inhabit stiC-leaf foliage, which were originally highlighted with paint (Figs 1, 2).1 The capitals sit upon a highly sophisticated pier design formed by a central cruciform support with triple shafts at each termination and in the angles, which oCered the possibility for a range of continuous and individual sculpted designs in the capitals above (Fig. -

2006 Calvin Bibliography

2006 Calvin Bibliography Compiled by Paul Fields I. Calvin's Life and Times A. Biography B. Cultural Context Intellectual History C. Cultural Context Social History D. Friends and Associates E. Polemical Relationships II. Calvin's Works A. Works and Selections B. Critique III. Calvin's Theology A. Overview B. Doctrine of God 1. Overview 2. Creation 3. Knowledge of God 4. Providence 5. Trinity C. Doctrine of Christ D. Doctrine of Salvation 1. Overview 2. Atonement 3. Deification 4. Faith 5. Justification 6. Predestination E. Doctrine of Humanity 1. Covenant 2. Grace 3. Image of God 4. Law 5. Natural Law 6. Soul 7. Free Will F. Doctrine of Christian Life 1. Angels 2. Piety 3. Prayer 4. Sanctification 5. Vows G. Ecclesiology 1. Overview 2. Discipline 3. Polity H. Worship 1. Overview 2. Buildings 3. Images 4. Liturgy 5. Mariology 6. Music 7. Preaching and Sacraments IV. Calvin and SocialEthical Issues V. Calvin and Political Issues VI. Calvinism A. Theological Influence 1. Christian Life 2. Ecclesiology 3. Eschatology 4. Lord's Supper 5. Natural Law 6. Preaching 7. Predestination 8. Salvation 9. Worship B. Cultural Influence 1. Arts 2. Education 3. Literature 4. Printing C. Social, Economic, and Political Influence D. International Influence 1. Croatia 2. England 3. Europe 4. France 5. Germany 6. Hungary 7. Korea 8. Latin America 9. Netherlands 10. Poland 11. Scotland 12. United States E. Critique F. Book Reviews G. Bibliographies I. Calvin’s Life and Times A. Biography Cottret, Bernard. “Noms de lieux: Ignace de Loyola, Jean Calvin, John Wesley.” Études Théologiques et Religieuses 80, no. -

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

Eighteenth-Century English and French Landscape Painting

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2018 Common ground, diverging paths: eighteenth-century English and French landscape painting. Jessica Robins Schumacher University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Schumacher, Jessica Robins, "Common ground, diverging paths: eighteenth-century English and French landscape painting." (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3111. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/3111 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMON GROUND, DIVERGING PATHS: EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANDSCAPE PAINTING By Jessica Robins Schumacher B.A. cum laude, Vanderbilt University, 1977 J.D magna cum laude, Brandeis School of Law, University of Louisville, 1986 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art (C) and Art History Hite Art Department University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2018 Copyright 2018 by Jessica Robins Schumacher All rights reserved COMMON GROUND, DIVERGENT PATHS: EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH AND FRENCH LANDSCAPE PAINTING By Jessica Robins Schumacher B.A. -

The Hanseatic League in England

Journal of Accountancy Volume 53 Issue 5 Article 6 5-1932 Herrings and the First Great Combine, Part II: The Hanseatic League in England Walter Mucklow Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/jofa Part of the Accounting Commons Recommended Citation Mucklow, Walter (1932) "Herrings and the First Great Combine, Part II: The Hanseatic League in England," Journal of Accountancy: Vol. 53 : Iss. 5 , Article 6. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/jofa/vol53/iss5/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Archival Digital Accounting Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Accountancy by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Herrings and the First Great Combine PART II The Hanseatic League in England By Walter Mucklow The Site From the earliest times the German merchants had a depot behind Cannon street station, near the foot of the narrow Dow gate hill bordering the west side of the station. Apparently this neighborhood had for centuries been a centre of activities, for in few London streets have there been found more Roman remains than in Thames street, along a part of which ran the old Roman river wall, built on oak piles, overlaid by a stratum of chalk and stone and covered with hewn sandstone set in cement. In places this wall is twenty feet thick and some of the beams were 18 inches square. The Easterlings, as the early German merchants were called, first settled here and occupied the Hall of the Easterlings: later the merchants of Cologne held a part of Dowgate: and subse quently these two united, being then known as the “Merchants of Almaigne” and owned the “Dutch Guildhall.” The site was important, for in early times Dowgate was the only city gate opening to the river; therefore, it controlled foreign traffic and was of great value to the Germans in their efforts to govern this important business. -

KAISER IS KISI 1— I 3Grtg?G\Rgvgcj3l Want of Every Housewife— and There's System Permits You to Buy Bonn— Emperor William Left Feer» Yes- L^Gj^Oujwf^V

PAUI, THE ST. ULOBE, SUNDAY, APRH, 38, 19Ol# After being taken out he was delirious AFTERNOON NEWS CONDENSED. for hours. "Something new"—that's the great ;V^VUR EQUITABLE CREDIT I hi hi LtnUUn iiiLft1LliO KAISER IS KISI 1— I_3grtg?g\rgVgCj3l want of every housewife— and there's System permits you to buy Bonn— Emperor William left feer» yes- l^gj^oUjWf^V . \J I' DISTRESS IN PORTO RICO terday morning. nothln S ln the WOrld that . will brighten for lowest prices, paying a little ! New York—Marshal C. Balm. a con- J*^HSlfil3fiJfSfßfct* up petition i and cheer a room or house as a down weekly ARTHUR STRINGENCY OP MONET CAUSES OF PRESIDED THIS tractor, filed a In bankruptcy balance or monthly f SIR SULLIVAN'S POSTHU- AT INITIATION OF yrith of $175,5?5; no ftZiL-1^ -JV^MISfIT-1^ liabilities assets. new flo covering. Three things • MOUS "THE EMERALD ISLE" COMSrBROIAL MORTALITY. HIS ®OW INTO STUDENTS' • as best suits you. 1 Chicago—A poc*' roomY located over the V. l'il*ll''""l'»IJ —: 27.—A - ™*-. Car- ." \u25a0 " \u25a0 - AT THE SAVOY SAN JUAN, Porto Rico. April CORPS BORUSSIA saloon of two vpell knpwn local politi- .i'rv^ must be consJdertd In selecting —i- troopers —'• —— mounted battalion of native ar- cians, was raided by detectives. Twenty pets or Rugs— the fabric, today by the patterns and the dyes used In the / $lET&L BEDS. i rived here and were reviewed arrested. \u25a0 ir.en were making. • > : _ Lieut. Col. James A. Buchanan, of the Albany, N. -

Competing English, Spanish, and French Alabaster Trade in Europe Over Five Centuries As Evidenced by Isotope Fingerprinting

Competing English, Spanish, and French alabaster trade in Europe over five centuries as evidenced by isotope fingerprinting W. Kloppmanna,1, L. Lerouxb, P. Brombletc, P.-Y. Le Pogamd, A. H. Coopere,2, N. Worleyf,2, C. Guerrota, A. T. Montecha, A. M. Gallasa, and R. Aillaudg aBRGM (Bureau de Recherches Géologiques et Minières, French Geological Survey), 45060 Orléans, France; bCentre de Recherche sur la Conservation- Laboratoire de Recherche des Monuments Historiques (CRC-LRMH) USR3224, 77420 Champs-sur-Marne, France; cCentre Interdisciplinaire de Conservation et Restauration du Patrimoine (CICRP), Belle-de-Mai, 13003 Marseille, France; dDépartement des Sculptures, Musée du Louvre, 75058 Paris, France; eRetired from British Geological Survey, Keyworth, Nottingham, NG12 5GG, United Kingdom; fRetired from British Gypsum, Nottingham, NG16 AL, United Kingdom; and gLa Touche, 38220 Notre-Dame-de-Mésage, France Edited by Thure E. Cerling, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, and approved September 20, 2017 (received for review May 5, 2017) A lack of written sources is a serious obstacle in the reconstruction of 1414 (10, 12). After the banning of religious representations, the medieval trade of art and art materials, and in the identification shiploads of alabaster artworks were sent to France (13). In of artists, workshop locations, and trade routes. We use the isotopes England, only a few sculptures escaped the plaster furnaces by of sulfur, oxygen, and strontium (S, O, Sr) present in gypsum being hidden and were retrieved centuries later (14). In contrast, alabaster to unambiguously link ancient European source quarries western and northern France was inundated with outlawed and areas to alabaster artworks produced over five centuries (12th– English artworks. -

Freshfield Int Info BLANK INT INFO DR

Freshfield Station Interchange Information Buses that operate near this station Buses from stop A Buses from stop B Buses from stop D From 24/07/2016 From 24/07/2016 From 24/07/2016 Formby Circular Formby Circular Formby Circular F5 Via Harington Road, Woodlands Road, Kirklake Road, Formby Bridge, F4 Via Gores Lane, Hasall Lane, Three Tuns Lane F1 Via Massam’s Lane, Green Lane, Ryeground Lane, Southport Road, Duke Street, Three Tuns Lane Deansgate Lane, Watchyard Lane, Smithy Green, Kenyons Lane, School Lane, Church Road Mondays to Fridays Saturdays Sundays Mondays to Fridays Saturdays Sundays 7am 0718 7am 0718 No service 7am 0755 7am 0755 No service Mondays to Fridays Saturdays Sundays 8am 0810 8am 0810 No service Then every hour at 18 minutes Then every hour at 18 minutes Then every hour at 55 minutes Then every hour at 55 minutes past each hour until past each hour until past each hour until past each hour until Then every hour at 10 minutes Then every hour at 10 minutes past each hour until past each hour until 6pm 1818 6pm 1818 6pm 1855 6pm 1855 Operated by Cumfybus Operated by Cumfybus 7pm 1910 7pm 1910 Operated by Cumfybus From 24/07/2016 From 24/07/2016 Formby Circular Formby Circular From 24/07/2016 F6 Via Harington Road, Woodlands Road, Formby Bridge, Duke Street, F6 Via Massam’s Lane, Green Lane, Southport Road, Deansgate Lane, Formby Circular Three Tuns Lane, Sumner Road, Elbow Lane, Liverpool Road, Watchyard Lane, Smithy Green, Kenyons Lane, School Lane, F2 Via Kings Road, Formby Station, Duke Street, Three Tuns Lane Alt -

Tracts and Other Papers Relating Principally to the Origin, Settlement

Library of Congress Tracts and other papers relating principally to the origin, settlement, and progress of the colonies in North America from the discovery of the country to the year 1776. Collected by Peter Force. Vol. 3 TRACTS AND OTHER PAPERS, RELATING PRINCIPALLY TO THE ORIGIN, SETTLEMENT, AND PROGRESS OF THE COLONIES IN NORTH AMERICA, FROM THE DISCOVERY OF THE COUNTRY TO THE YEAR 1776. 2 219 17?? Oct13 COLLECTED BY PETER FORCE. Vol. III. WASHINGTON: PRINTED BY WM. Q. FORCE. 1844. No. 2 ? Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1844, By PETER FORCE, In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the District of' Columbia. 7 '69 CONTENTS OF THE THIRD VOLUME. 3 390 ? 62 I. A Trve Declaration of the estate of the Colonie in Virginia, with a confutation of such scandalous reports as haue tended to the disgrace of so worthy an enterprise. Published Tracts and other papers relating principally to the origin, settlement, and progress of the colonies in North America from the discovery of the country to the year 1776. Collected by Peter Force. Vol. 3 http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbcb.7018c Library of Congress by aduise and direction of the Councell of Virginia. London, printed for William Barret, and are to be sold at the blacke Beare in Pauls Church-yard. 1610.—[28 pages.] II. For the Colony in Virginea Britannia. Lavves Diuine, Morall and Martiall, &c. Alget qui non Ardet. Res nostrœ subinde non sunt, quales quis optaret, sed quales esse possunt. Printed at London for Walter Burre.