Richard Smit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Examination of the Concept of Reincarnation in African Philosophy

AN EXAMINATION OF THE CONCEPT OF REINCARNATION IN AFRICAN PHILOSOPHY by HASSKEI MOHAMMED MAJEED submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF LITERATURE AND PHILOSOPHY in the subject PHILOSOPHY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROF. M. B. RAMOSE JANUARY 2012 CONTENTS Declaration vi Acknowledgement vii Key Terms viii Summary ix INTRODUCTION x Problem Statement x Methodology xi Structure of the Dissertation xii PART ONE 1 Belief in Reincarnation in some Ancient Cultures 1 CHAPTER ONE: EGYPTIAN BELIEF 2 1.1 Immortality and Reincarnation 7 1.2 Egypt and Africa 12 1.3 On the Meaning of Africa 17 CHAPTER TWO: GREEK BELIEF 19 CHAPTER THREE: INDIAN BELIEF 25 ii CHAPTER FOUR: CHINESE BELIEF 36 CHAPTER FIVE: INCA BELIEF 40 Conclusion for Part One 49 PART TWO 52 Personal Identity: A Prelude to Reincarnation 52 CHAPTER SIX: PERSONAL IDENTITY 52 6.0.0 On What Does Personal Identity Depend? 52 6.1.0 The Ontological Question in African Philosophy of Mind 55 6.1.1. Mind as a Disembodied Self-knowing Entity 56 6.1.2. Some Criticisms 64 6.1.2.1 Mind has no Akan Equivalent 65 6.1.2.2 Mind is Meaningless, Nonsensical, and Nonexistent 86 6.1.2.3 Mind is Bodily 96 6.1.2.3.1 Mind Signifies Mental or Brain Processes Identifiable with the Body 96 6.1.2.3.2 Bodily Identity as either a Fundament or Consequent 97 (a) Body as a Fundament 97 (b) Body as Consequent 106 6.1.2.4 Mind is neither Body-dependent nor a Disembodied Entity 107 6.1.3 Synthesis: Materialism, Physicalism, and Quasi-physicalism 111 6.2.0 The Normative Question in African Philosophy of Mind 121 6.3.0 Persistence (Survival) 123 iii PART THREE 128 Reincarnation in African Philosophy 128 CHAPTER SEVEN: THE DOCTRINE OF REINCARNATION IN AFRICAN THOUGHT 128 7. -

Karmapa Karma Pakshi (1206-1283)

CUỘC ĐỜI SIÊU VIỆT CỦA 16 VỊ TỔ KARMAPA TÂY TẠNG Biên soạn: Karma Thinley Rinpoche Nguyên tác: The History of Sixteen Karmapas of Tibet Karmapa Rangjung Rigpe Dorje XVI Karma Thinley Rinpoche - Việt dịch: Nguyễn An Cư Thiện Tri Thức 2543-1999 THIỆN TRI THỨC MỤC LỤC LỜI NÓI ĐẦU ............................................................................................ 7 LỜI TỰA ..................................................................................................... 9 DẪN NHẬP .............................................................................................. 12 NỀN TẢNG LỊCH SỬ VÀ LÝ THUYẾT ................................................ 39 Chương I: KARMAPA DUSUM KHYENPA (1110-1193) ...................... 64 Chương II: KARMAPA KARMA PAKSHI (1206-1283) ......................... 70 Chương III: KARMAPA RANGJUNG DORJE (1284-1339) .................. 78 Chương IV: KARMAPA ROLPE DORJE (1340-1383) ........................... 84 Chương V: KARMAPA DEZHIN SHEGPA (1384-1415) ........................ 95 Chương VI: KARMAPA THONGWA DONDEN (1416-1453) ............. 102 Chương VII: KARMAPA CHODRAG GYALTSHO (1454-1506) ........ 106 Chương VIII: KARMAPA MIKYO DORJE (1507-1554) ..................... 112 Chương IX: KARMAPA WANGCHUK DORJE (1555-1603) .............. 122 Chương X: KARMAPA CHOYING DORJE (1604-1674) .................... 129 Chương XI: KARMAPA YESHE DORJE (1676-1702) ......................... 135 Chương XII: KARMAPA CHANGCHUB DORJE (1703-1732) ........... 138 Chương XIII: KARMAPA DUDUL DORJE (1733-1797) .................... -

YEAR 6/2019 KAGYU SAMYE LING: Meditation

YEAR 6/2019 KAGYU SAMYE LING: meditation & yoga retreat – with cat & phil Eskdalemuir, Dumfriesshire, Scotland Kagyu Samye Ling - tibetan buddhist centre/kagyu tradition Thursday, 8th – Sunday, 11th August 2019 Cost: £350 tuition (includes donation to Kagyu Samye Ling) This is an additional way we have chosen to support the monastery & their ongoing charitable work. Accommodation to be booked directly with Samye Ling. Deposit: £200 to hold a space – (FULL CAPACITY – PREVIOUS YEARS) Balance due: 8th June (two months prior) – NO REFUNDS AFTER THIS DATE Payment methods: cash/cheque/bank transfer Cheques made out to: Catherine Alip-Douglas Bank transfer to: TSB – Bayswater Branch, 30-32 Westbourne Grove sort code: 309059, account number:14231860, Swift/BIC code: IBAN:GB49TSBS30905914231860 BIC: TSBSGB2AXXX The Retreat: 3 nights/4 days includes a tour of samye ling, daily yoga sessions (2- 2.5hours), lectures, meditation practice with Samye Ling’s sangha, a film screening of “AKONG” based on Akong Rinpoche, one of the founders of KSL and informal gatherings in an environment conducive to a proper ‘retreat’. As always, this retreat is also part of the Sangyé Yoga School's 2019 TT. There will be time for walks in the beautiful surroundings and reading books from their well-stocked and newly expanded gift shop. NOT INCLUDED: accommodation (many options depending on your budget) & travel. Kagyu Samye Ling provides the perfect environment to reconnect with nature, go deeper in your meditation practice, learn about the foundations of Tibetan Buddhism and the Kagyu lineage. It is a simple retreat for students who want to get to the heart of a practice and spend more time than usual in meditation sessions. -

Living a Mindful Life: an Hermeneutic Phenomenological Inquiry Into the Lived Experience of Secular Mindfulness, Compassion and Insight

LIVING A MINDFUL LIFE: AN HERMENEUTIC PHENOMENOLOGICAL INQUIRY INTO THE LIVED EXPERIENCE OF SECULAR MINDFULNESS, COMPASSION AND INSIGHT _______________________________________________________________ A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Aberdeen Jane Kellock Arnold MA (hons) in Philosophy and Psychology, University of Edinburgh (1985); MSW in Social Work, University of Edinburgh (1996) 1 DECLARATION I have composed this thesis myself. It is the record of my own work and it has not been presented to this or any other university in support of an application for any degree or professional qualification other than that of which I am now a candidate. Any personal data have been processed in accordance with the provision of the Data Protection Act (1998); all quotations have been distinguished by quotation marks and sources of information and help specifically acknowledged. Signed: ...................................................................... Jane Kellock Arnold Uphall, West Lothian, April 2018 2 ABSTRACT This research study explores the experience and effects of long-term practice by six student practitioners of secular mindfulness, compassion and insight forming the Mindfulness-Based Living model incorporated into the MSc in Mindfulness Studies at the University of Aberdeen. A review of existing literature on the topic of mindfulness highlights that research is predominantly postpositivist and quantitative in approach, only recently incorporating limited qualitative studies, and is focused chiefly on mindfulness as a treatment for a range of mental and physical disorders. However, the nature of mindfulness particularly when practised in conjunction with compassion and insight suggests that it is a more intense, complex, nuanced and pervasive experience than is reflected in the literature. -

Tibetan Buddhism, Vajrayana, and the Lineage of Chogyam Trunpa

Tibetan Buddhism, Vajrayana, and the lineage of Chögyam Trungpa, Rinpoche The Vajrayana is the third major yana or vehicle of buddhadharma. It is built on and incorporates the Foundational teachings (Hinayana) and the Mahayana. It is also known as the Secret Mantra. The Vajrayana teachings are secret teachings, passed down through lineages from teacher to student. They were preserved and developed extensively in Tibet over 1200 years. The beginnings of Vajrayana are in India, initially spreading out through areas of Mahayana Buddhism and later the Kushan Empire. By the 12th century most of the Indian subcontinent was overtaken by the Moghul Empire and almost all of Buddhism was suppressed. The majority of Vajrayana texts, teachings and practices were preserved intact in Tibet. Vajrayana is characterized by the use of skillful means (upaya), expediting the path to enlightenment mapped out in the Mahayana teachings. The skillful means are an intensification of meditation practices coupled with an advanced understanding of the view. Whereas the conventional Mahayana teachings view the emptiness of self and all phenomena as the final goal on the path to Buddhahood, Vajrayana starts by acknowledging this goal as already fully present in all sentient beings. The practice of the path is to actualize that in ourselves and all beings through transforming confusion and obstacles, revealing their natural state of primordial wisdom. This is accomplished through sacred outlook (view), and employing meditation techniques such as visualization in deity practice and mantra recitation. One major stream of Vajrayana is known as Mahamudra (Great Seal), which incorporates the techniques noted above in a process of creation (visualization, mantra) and completion (yogas) leading to the Great Seal. -

Spring/Summer 2010 in This Issue

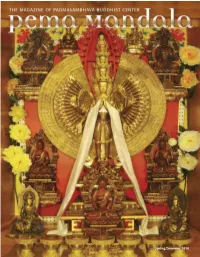

Spring/Summer 2010 In This Issue 1 Letter from the Venerable Khenpo Rinpoches 2 Brilliant Lotus Garland of Glorious Wisdom A Glimpse into the Ancient Lineage of Khenchen Palden Volume 9, Spring/Summer 2010 Sherab Rinpoche A Publication of 6 Entrusted: The Journey of Khenchen Rinpoche’s Begging Bowl Padmasambhava Buddhist Center 9 Fulfillment of Wishes: Nyingma Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism Eight Great Stupas & Five Dhyani Buddhas Founding Directors 12 How I Met the Khenpo Rinpoches Ven. Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche Ven. Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche 14 Schedule of Teachings 16 The Activity Samayas of Anuyoga Ani Lorraine, Co-Editor An Excerpt from the 2009 Shedra, Year 7: Anuyoga Pema Dragpa, Co-Editor Amanda Lewis, Assistant Editor 18 Garland of Views Pema Tsultrim, Coordinator Beth Gongde, Copy Editor 24 The Fruits of Service Michael Ray Nott, Art Director 26 2009 Year in Review Sandy Mueller, Production Editor PBC and Pema Mandala Office For subscriptions or contributions to the magazine, please contact: Padma Samye Ling Attn: Pema Mandala 618 Buddha Highway Sidney Center, NY 13839 (607) 865-8068 [email protected] Pema Mandala welcomes all contributions submitted for consideration. All accepted submissions will be edited appropriately for Cover: 1,000 Armed Chenrezig statue with the publication in a magazine representing the Five Dhyani Buddhas in the Shantarakshita Padmasambhava Buddhist Center. Library at Padma Samye Ling Please email submissions to Photographed by Amanda Lewis [email protected]. © Copyright 2010 by Padmasambhava Buddhist Center International. Material in this publication is copyrighted and may not be reproduced by photocopy or any other means without obtaining written permission from the publisher. -

MINDFUL HEROES Stories of Journeys That Changed Lives

MINDFUL HEROES stories of journeys that changed lives Edited by Terry Barrett, Vin Harris and Graeme Nixon Everyone loves a good story. This book tells the stories of a constellation of Mindful Heroes: ordinary people just like us, who followed the path of mindfulness and went on an inner journey that would change their world. They engaged with an in-depth study and courageous exploration of mindfulness practice. Having experienced for themselves the benefits of mindful awareness, compassion and insight, they then wanted to give others the opportunity to discover their own potential. These 26 Mindful Heroes from 10 countries creatively applied mindfulness to a variety of settingsacross Education, Health, Business, Sport, Creative Artsand Community work. Now they share the moving stories of their personal and professional journeys of transformation with you. "As the old saying goes, 'It is not what happens on the cushion, it is what we take out into the world.' Mindful Heroes exemplifies this notion, exploring the lives of those who have not only experienced the personal benefits of meditation, but those who have gone on to make it their passion and purpose in life, planting the seeds of awareness and compassion for the benefit of us all." Andy Puddicombe author of The Headspace Guide to Mindfulness & Meditation: 10 minutes can make the difference. Co-Founder http://www.headspace.com "This is a wonderful book. It reminds us that we are all heroes, due to the power of our own minds. The living examples presented in these pages help to make the mindful path accessible and relatable. -

Studies on Ethnic Groups in China

Kolas&Thowsen, Margins 1/4/05 4:10 PM Page i studies on ethnic groups in china Stevan Harrell, Editor Kolas&Thowsen, Margins 1/4/05 4:10 PM Page ii studies on ethnic groups in china Cultural Encounters on China’s Ethnic Frontiers Edited by Stevan Harrell Guest People: Hakka Identity in China and Abroad Edited by Nicole Constable Familiar Strangers: A History of Muslims in Northwest China Jonathan N. Lipman Lessons in Being Chinese: Minority Education and Ethnic Identity in Southwest China Mette Halskov Hansen Manchus and Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861–1928 Edward J. M. Rhoads Ways of Being Ethnic in Southwest China Stevan Harrell Governing China’s Multiethnic Frontiers Edited by Morris Rossabi On the Margins of Tibet: Cultural Survival on the Sino-Tibetan Frontier Åshild Kolås and Monika P. Thowsen Kolas&Thowsen, Margins 1/4/05 4:10 PM Page iii ON THE MARGINS OF TIBET Cultural Survival on the Sino-Tibetan Frontier Åshild Kolås and Monika P. Thowsen UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS Seattle and London Kolas&Thowsen, Margins 1/7/05 12:47 PM Page iv this publication was supported in part by the donald r. ellegood international publications endowment. Copyright © 2005 by the University of Washington Press Printed in United States of America Designed by Pamela Canell 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 5 4 3 2 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be repro- duced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without permission in writ- ing from the publisher. -

Chös Khor Ling the Great Difference Between Us As Marpa House and Rectory Lane Other Buddhist Centres Is That We, the Lay Students, All Ashdon of Us, Run It

chös khor marpa house news ling Winter 2011/2012 BUDDHIST MEDITATION AND RETREAT CENTRE Summer 2016 Summer is Here (and Now) From The Trustees • From The Committee The Celebration of Vajrayana Buddhism Coming to the West Chime Rinpoche at the Buddhist Society A Welsh Idyll • Tibetan Alphabet Construction • Goodbye Yasuko Nomura chös Trustee News his time of our 50th-year celebration gives us room Tto think. We are an unusual centre. We often have odd tales of how we came to this place, nestled invisibly khor in Ashdon. Some of us experienced being inexplicably drawn here. Many felt 'magnetised' so that we cannot and do not want to ever part. From the centre, from ling our Lama, from each other. This is not a floppy fantasy relationship. It is viscerally BUDDHIST real, exposing our flaws, our upsets and the flaws of MEDITATION AND others. Sometimes we want to be shot of it all and RETREAT CENTRE wallow in the world's outside 'delights'. Sometimes we drift away long distances – but, like planets, we orbit our sun. Some are quite a long way out, like Pluto. I prefer a different metaphor – that we are bound by an elastic cord that lengthens and lengthens but eventually reaches its limit and back we zoom. Reality is frustrating because we know enough to realise that the outside 'delights' do not lead to any safe place. Somehow, some secret is only found here. This isn't the transitory brainwashing of a cult. This is no restricted, gated community from which we cannot escape. Indeed Marpa House is so intense that it is almost impossible to remain living here for more than a year or two. -

The Karmapa Controversy

The Karmapa controversy A compilation of information 1 Foreword This work fills a requirement: to provide all meaningful information for a good understanding about the Karmapa controversy which, since 1992, shakes up the Karma Kagyu lineage. While web surfing, one can notice the huge information unbalance between the two differing sides: on Situ Rinpoche's side, there is plenty of documentation, while that on Shamar Rinpoche's side is sparse. On Situ Rinpoche's side, many websites give out information, with some, dedicated to this task, having almost daily updates. By comparison, Shamar Rinpoche side does not even provide the minimum information sufficient to understand its point of view. Now, complete information easily found is essential for everyone to make up one's opinion. To limit oneself to only one version of the facts does not allow for a full understanding and leads to all extremes, which we have sorely witnessed since 1992. Studying this controversy, one is surprised by the distressing level of disinformation and ignorance surrounding it. Few people know truly the circumstances and the unfolding of all these events which profoundly shook our lineage. Most contented themselves with adopting the view point of their entourage, siding either way, bringing up real quarrels and polemics between disciples of the same masters. It even came up to murders and monasteries attacks ! And yet, without going for any debate or confrontation, simply acquainting oneself with information provided by each side, allows us to stand back, to grasp the ins and outs in a more objective way and finally to reach a valid opinion in this matter. -

A Short Biography of Four Tibetan Lamas and Their Activities in Sikkim

BULLETIN OF TIBETOLOGY 49 A SHORT BIOGRAPHY OF FOUR TIBETAN LAMAS AND THEIR ACTIVITIES IN SIKKIM TSULTSEM GYATSO ACHARYA Namgyal Institute of Tibetology Summarised English translation by Saul Mullard and Tsewang Paljor Translators’ note It is hoped that this summarised translation of Lama Tsultsem’s biography will shed some light on the lives and activities of some of the Tibetan lamas who resided or continue to reside in Sikkim. This summary is not a direct translation of the original but rather an interpretation aimed at providing the student, who cannot read Tibetan, with an insight into the lives of a few inspirational lamas who dedicated themselves to various activities of the Dharma both in Sikkim and around the world. For the benefit of the reader, we have been compelled to present this work in a clear and straightforward manner; thus we have excluded many literary techniques and expressions which are commonly found in Tibetan but do not translate easily into the English language. We apologize for this and hope the reader will understand that this is not an ‘academic’ translation, but rather a ‘representation’ of the Tibetan original which is to be published at a later date. It should be noted that some of the footnotes in this piece have been added by the translators in order to clarify certain issues and aspects of the text and are not always a rendition of the footnotes in the original text 1. As this English summary will be mainly read by those who are unfamiliar with the Tibetan language, we have refrained from using transliteration systems (Wylie) for the spelling of personal names, except in translated footnotes that refer to recent works in Tibetan and in the bibliography. -

Funeral Advice for Buddhists in the Tibetan Tradition 'When I

Funeral advice for Buddhists in the Tibetan tradition as advised by Akong Tulku Rinpoche & ‘When I go’ a summary of your wishes Buddhist Funeral Services KAGYU SAMYE LING MONASTERY & TIBETAN CENTRE Eskdalemuir, Langholm, Dumfries & Galloway, Scotland, DG13 0QL Tel: 013873 73232 ext 1 www.samyeling.org E-mail: [email protected] Funeral advice for Buddhists, according to the Tibetan tradition We hope the enclosed information will be useful to Buddhists and their carers when the time comes for them to die. Buddhists believe that consciousness survives physical death and, following an interval (bardo), rebirth will usually take place. If we are not prepared, death can be a confusing and terrifying experience. With preparation, it can be an opportunity for attaining higher rebirth or even enlightenment, so we offer this information, which includes practical arrangements as well as spiritual care, in the hope that it will help as many people as possible during this special time. The topics covered include traditional practices performed for the dying person, main points to consider when we’re dying or accompanying a Buddhist who’s dying, organ donation, typical funeral service, practical arrangements to consider, storing cremated remains and a list of various services and products available at Samye Ling. After reading, a summary of your wishes can then be contained in the enclosed ‘When I go’ documents and given to those close to you. These also include information to give to nurses and undertakers. It’s useful to carry a summary of the information on you, as in the Buddhist ‘I.D.’ card (see ‘Various Services’ document), since executors and funeral directives may not be readily available.