Unraveling the Mystery of the Hidden Treasure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism

Journal of Education & Social Policy Vol. 1 No. 1; June 2014 Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism Shahida Bilqies Research Scholar, Shah-i-Hamadan Institute of Islamic Studies University of Kashmir, Srinagar-190006 Jammu and Kashmir, India. Sufism, being the marrow of the bone or the inner dimension of the Islamic revelation, is the means par excellence whereby Tawhid is achieved. All Muslims believe in Unity as expressed in the most Universal sense possible by the Shahadah, la ilaha ill’Allah. The Sufi has realized the mysteries of Tawhid, who knows what this assertion means. It is only he who sees God everywhere.1 Sufism can also be explained from the perspective of the three basic religious attitudes mentioned in the Qur’an. These are the attitudes of Islam, Iman and Ihsan.There is a Hadith of the Prophet (saw) which describes the three attitudes separately as components of Din (religion), while several other traditions in the Kitab-ul-Iman of Sahih Bukhari discuss Islam and Iman as distinct attitudes varying in religious significance. These are also mentioned as having various degrees of intensity and varieties in themselves. The attitude of Islam, which has given its name to the Islamic religion, means Submission to the Will of Allah. This is the minimum qualification for being a Muslim. Technically, it implies an acceptance, even if only formal, of the teachings contained in the Qur’an and the Traditions of the Prophet (saw). Iman is a more advanced stage in the field of religion than Islam. It designates a further penetration into the heart of religion and a firm faith in its teachings. -

Islamic Liberation Theology Reading List

ISLAMIC LIBERATION THEOLOGY READING LIST Note: In the spirit of robust inquiry and discussion, we chose to present authors from a wide range of intellectual and political commitments, some of whose writings conflict with others, and some we may not even agree with ourselves. This list is not an endorsement of all the texts, authors, and their views, but rather a starting point for critically exploring the place of Islam in liberation, justice, solidarity, and the long work ahead to transform our communities. GENDER, SEXUALITY, AND FEMINISM Sexual Ethics and Islam: Feminist Reflections on Qur'an, Hadith, and Jurisprudence by Kecia Ali Before Homosexuality in the Arab-Islamic World, 1500-1800 by Khaled El- Rouayheb American Muslim Women, Religious Authority, and Activism: More Than a Prayer by Juliane Hammer Women of the Nation: Between Black Protest and Sunni Islam by Dawn-Marie Gibson and Jamillah Karim Homosexuality in Islam: Critical Reflection on Gay, Lesbian and Transgender Muslims by Scott Kugle Politics of Piety: The Islamic Revival and the Feminist Subject by Saba Mahmood Being Muslim: A Cultural History of Women of Color in American Islam by Sylvia Chan-Malik The Veil And The Male Elite: A Feminist Interpretation Of Women's Rights In Islam by Fatima Mernissi The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire by Leslie P. Peirce Sufi Narratives of Intimacy: Ibn Arabi, Gender and Sexuality by Sa'diyya Shaikh Inside the Gender Jihad: Women's Reform in Islam by Amina Wadud LAW AND THEOLOGY Islamic Family Law in a Changing World: A Global Resource Book by Abdullahi A. -

EXAMINING the WRITINGS of NANA Asmasu: AN

!"#$%&%&'()*!(+,%)%&'-(./(&#&#(#-$#012(#&(%&3!-)%'#)%.&(./(4#-).,#5( 6.&&!6)%.&-(#$.&'(6.&)!$4.,#,7(-1/%(+.$!&( ( A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies By 589:;<=;($8>;??8@(AB#B( ( ( ( Georgetown University Washington, D.C. 3/26/12 !"#$%&%&'()*!(+,%)%&'-(./(&#&#(#-$#012(#&(%&3!-)%'#)%.&(./(4#-).,#5( 6.&&!6)%.&-(#$.&'(6.&)!$4.,#,7(-1/%(+.$!&( ( 589:;<=;($8>;??8@(A#( ( $;<DE:2(F:B(GEH<(3E??@(4HF( ( #A-),#6)( ( &8<8(#IJ809@(DH;(K89LHD;:(EM(8(N:EJC<;<D(&CL;:C8<(IH8OPH(H;?K(8(?;8KC<L( :E?;(C<(N:EQCKC<L(:;?CLCE9I(C<ID:9=DCE<(DE(DH;(REJ;<(EM(DH;(-EPEDE(68?CNH8D;(C<(DH;( STUUIB((#IJ809(CI(8<(;V8JN?;(EM(J8<O(-9MC(REJ;<(RHEI;(:E?;(8<K(=E<D:CW9DCE<( H8Q;(N:EQCK;K(DH;J(DH;(ENNE:D9<CDO(DE(K;Q;?EN(N8IDE:8?(=E<<;=DCE<IB(()HEI;( =E<<;=DCE<I(=E<ICID(EM(CJN8:DC<L(:;?CLCE9I(D;8=HC<LI(8I(R;??(8I(KCIN;<IC<L(:;?CLCE9I( L9CK8<=;B(( ( )HCI(DH;ICI(;VN?E:;I(DH;(DENC=(WO(;ID8W?CIHC<L(DH;(N:;I;<=;(EM(-9MC(REJ;<( 8?E<LICK;(J;<(;8:?O(8D(DH;(W;LC<<C<L(EM(%I?8JB((-EJ;(EM(DH;I;(REJ;<(=E<D:CW9D;K(C<( Q8?98W?;(R8OI(DE(DH;(L:ERDH(EM(DH;(-9MC(R8OB((*CLH?CLHDC<L(DH8D(NEC<D(K;JE<ID:8D;I( 8<(;8:?O(C<QE?Q;J;<D(EM(REJ;<(C<(-9MCIJB(()H;(I9WI;X9;<D(=H8ND;:(K;?Q;I(C<DE(DH;( WCEL:8NHC;I(EM(M;J8?;(-9MC(I8C<DIY(DH;(<8D9:;(EM(DH8D(KCI=9IICE<(CI(DE(K:8R(DH;(I8C<D?O( =H8:8=D;:CIDC=I(DH8D(8:;(KCIDC<=D?O(M;JC<C<;B((#?IE@(WO(=CDC<L(DH;(;V8JN?;I(EM(-9MC( REJ;<0I(WCEL:8NHC;I@(DH;(KCI=9IICE<(N:EQCK;I(8(W8ICI(ME:(DH;C:(CJNE:D8<D( -

Sufism and Philosophy: Historical Interactions and Crosspollinations University of Birmingham, 26-27 April 2019

Sufism and Philosophy: Historical Interactions and Crosspollinations University of Birmingham, 26-27 April 2019 Conference programme Friday 26 April Introduction 10.00 – 10.15 Sophia Vasalou (Birmingham) and Richard Todd (Birmingham) Session 1: Early Philosophical Sufism 10.15 – 11.00 Joseph Lumbard (Doha), “Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī and the Art of Knowing” 11.00 – 11.30 Coffee Break 11.30 – 12.15 Mohammed Rustom (Abu Dhabi), “Devil’s Advocate: ʿAyn al-Quḍāt’s Satanology in Context” 12.15 – 13.45 Lunch Break Session 2: Philosophy and Sufism in Muslim Spain 13.45 – 14.30 Bethany Somma (Munich), “Andalusī Philosophers on Sufism and Not Living Like an Animal” 14.30 – 15.15 Maribel Fierro (Madrid), “Ibn Ṭufayl’s Ḥayy ibn Yaqẓān: An Almohad Reading” 15.15-15.45 Coffee Break Session 3: Sufism and the Avicennan Tradition 15.45 – 16.30 Cyrus Ali Zargar (Florida), “Mystical Union in a Rational Universe: The Incoherence, Avicennan Psychology, and ʿAṭṭār's Muṣībat-nāma” 16.30 – 17.15 Giovanni Martini (Bonn), “(Fictionally) Debating with Avicenna on the Role of the Intellect: ʿAlāʾ al-Dawla al-Simnānī’s Criticism of Philosophy and Rational Thinking in Context” 19.00 Conference dinner (by invitation) Saturday 27 April Session 4: Philosophical Sufism beyond the Classical Muslim World 9.30 – 10.15 Shankar Nair (Virginia), “‘Brahman Was a Hidden Treasure, Who Loved to Be Known…’: Philosophical Sufism and the Encounter with Sanskrit Non-Dualism” 10.15 – 10.45 Coffee Break 10.45 – 11.30 Muhammad Umar Faruque (New York), “Sufism and Philosophy in the Mughal- -

The Poems of Shah Ni'matullah Wali

SPECIAL ARTICLE ‘Prophecies’ in South Asian Muslim Political Discourse: The Poems of Shah Ni’matullah Wali c m naim Three “prophetic” Persian poems ascribed to a Shah n December 2009, Indian Chief of the Army Staff, General Ni’matullah Wali have been a fascinating feature in the Deepak Kapoor, made certain comments with reference to “the challenges of a possible ‘two-front war’ with China and popular political discourse of the Muslims of south Asia. I 1 Pakistan”. The Chinese response is not known, but public denun- For nearly two centuries these poems have circulated ciations in Pakistan were persistent, one Urdu column catching whenever there has been a major crisis in, what may be my particular attention. Orya Maqbool Jan, a former civil serv- called, the psychic world of south Asian Muslims. The ant, first declared that Napoleon lost at Waterloo because he neglec ted to consult his astrologer that morning.2 Next he urged first recorded appearance was in 1850, after the “Jihad” his readers and General Kapoor to heed what certain Muslim movement of Syed Ahmad had failed in the north-west, saints had already “foretold”, offering as his coup de grâce some followed by serial appearances after the debacle of 1857, verses from one of the Persian poems attributed to Shah the dissolution of the Ottoman Caliphate and the failure Ni’matullah Wali, prophesying that the Afghans would one day “conquer Punjab, Delhi, Kashmir, Deccan, and Jammu” and of the Khilafat and Hijrat movements in 1924, the “remov e all Hindu practices” from the land. Partition of the country and community in 1947, and the I was intrigued, since I had not seen any reference to the Indo-Pak war of 1971-72. -

SUFISM Emerald Hills of the Heart

Bölümler i Key Concepts in the Practice of SUFISM Emerald Hills of the Heart 3 ii Beware Satan! A Defense Strategy Bölümler iii Key Concepts in the Practice of SUFISM Emerald Hills of the Heart 3 M. Fethullah Gülen Translated by Ali Ünal New Jersey iv Beware Satan! A Defense Strategy Copyright © 2009 by Tughra Books 12 11 10 09 1 2 3 4 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the Publisher. Published by Tughra Books 26 Worlds Fair Dr. Unit C Somerset, New Jersey, 08873, USA www.tughrabooks.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data for the first volume Gulen, M. Fethullah [Kalbin zümrüt tepelerinde. English] Key concepts in the practice of Sufism / M. Fethullah Gulen. [Virginia] : Fountain, 2000. Includes index. ISBN 1-932099-23-9 1. Sufism - - Doctrines. I. Title. BP189.3 .G8413 2000 297.4 - - dc21 00-008011 ISBN-13 (paperback): 978-1-59784-204-4 ISBN-13 (hardcover): 978-1-59784-136-8 Printed by Çağlayan A.Ş., Izmir - Turkey Bölümler v TABLE OF CONTENTS The Emerald Hills of the Heart or Key Concepts in the Practice of Sufism ......vii Irshad and Murshid (Guidance and the Guide) ............................................. 1 Safar (Journeying) ........................................................................................9 Wasil (One who has Reached) ................................................................... 16 Samt ( Silence) ............................................................................................ 23 Halwat and Jalwat ( Privacy and Company) ................................................ 27 ‘Ilm Ladun (The Special Knowledge from God’s Presence) ........................ 32 Waliyy and Awliyaullah (God’s Friend [Saint] and God’s Friends [Saints]) .......37 Abrar (The Godly, Virtuous Ones) ...................................................... -

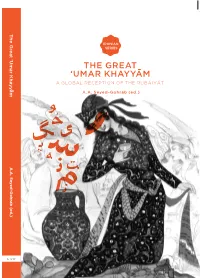

The Great 'Umar Khayyam

The Great ‘Umar Khayyam Great The IRANIAN IRANIAN SERIES SERIES The Rubáiyát by the Persian poet ‘Umar Khayyam (1048-1131) have been used in contemporary Iran as resistance literature, symbolizing the THE GREAT secularist voice in cultural debates. While Islamic fundamentalists criticize ‘UMAR KHAYYAM Khayyam as an atheist and materialist philosopher who questions God’s creation and the promise of reward or punishment in the hereafter, some A GLOBAL RECEPTION OF THE RUBÁIYÁT secularist intellectuals regard him as an example of a scientist who scrutinizes the mysteries of the universe. Others see him as a spiritual A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) master, a Sufi, who guides people to the truth. This remarkable volume collects eighteen essays on the history of the reception of ‘Umar Khayyam in various literary traditions, exploring how his philosophy of doubt, carpe diem, hedonism, and in vino veritas has inspired generations of poets, novelists, painters, musicians, calligraphers and filmmakers. ‘This is a volume which anybody interested in the field of Persian Studies, or in a study of ‘Umar Khayyam and also Edward Fitzgerald, will welcome with much satisfaction!’ Christine Van Ruymbeke, University of Cambridge Ali-Asghar Seyed-Gohrab is Associate Professor of Persian Literature and Culture at Leiden University. A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) A.A. Seyed-Gohrab WWW.LUP.NL 9 789087 281571 LEIDEN UNIVERSITY PRESS The Great <Umar Khayyæm Iranian Studies Series The Iranian Studies Series publishes high-quality scholarship on various aspects of Iranian civilisation, covering both contemporary and classical cultures of the Persian cultural area. The contemporary Persian-speaking area includes Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Central Asia, while classi- cal societies using Persian as a literary and cultural language were located in Anatolia, Caucasus, Central Asia and the Indo-Pakistani subcontinent. -

Negotiating Gender in the Mysticism of Ibn Al-‘Arabī and Francis of Assisi

TRANSCENDING THE FEMININE: NEGOTIATING GENDER IN THE MYSTICISM OF IBN AL-‘ARABĪ AND FRANCIS OF ASSISI A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Norma J. DaCrema May 2015 Examining Committee Members: Prof. Khalid Blankinship, Advisory Chair, Department of Religion Prof. Rebecca Alpert, Department of Religion Prof. Lucy Bregman, Department of Religion Dr. Eli Goldblatt, External Member, Department of English ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Abstract ................................................................................................................................v Dedication .......................................................................................................................... vi Acknowledgments............................................................................................................. vii List of Figures .................................................................................................................. viii Prologue ...............................................................................................................................x CHAPTER 1. MYSTICISM IN IBN AL-ʿARABĪ AND FRANCIS OF ASSISI: PREREQUISITES AND PROMISES ...............................................................1 Mysticism and Ibn al-ʿArabī .................................................................................... 4 Sharīʿah, Stations and States ..............................................................................7 -

The University of Chicago the Yazicioğlus and The

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE YAZICIOĞLUS AND THE SPIRITUAL VERNACULAR OF THE EARLY OTTOMAN FRONTIER A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY CARLOS GRENIER CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2017 © Copyright by Carlos Grenier, 2017. All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS v NOTES ON TRANSLITERATION vii INTRODUCTION 1 I. Who were the Yazıcıoğlus? 3 II. International Context 11 III. Sources 14 Comments 23 CHAPTER 1: THE SCRIBE AND HIS SONS 29 I. Yazıcı Ṣāliḥ and the ġāzīs of Rumelia 31 II. Meḥmed and Aḥmed, Sons of the Scribe 46 III. Problems 73 Conclusion 76 CHAPTER 2: THE YAZICIOĞLUS AND THE TEXTUAL GENEALOGIES OF OTTOMAN SUNNISM 80 I. Narrative Texts 86 II. Ḥadīth and Tafsīr Sources 93 III. Miscellaneous Sources 101 IV. Notes on Compositional Method 104 Patterns 106 CHAPTER 3: RELIGION ON THE FRONTIER 113 I. The Nature of the Borderland 118 II. “To know the bond of Islam”: From Sacred Knowledge to Communal Identity 137 Conclusion 156 CHAPTER 4: THE YAZICIOĞLUS WITHIN ISLAM 158 I. The Meaning of the Ibn ‘Arabī Tradition 159 II. Sufi Lineage and Community 178 III. The Shī‘ī-Sunnī Question 184 IV. Apocalypticism 191 Conclusion 206 iii CHAPTER 5: MAN AND COSMOS AT THE WORLD’S EDGE 208 I. Wonder and Ethics in the ‘Acāibü’l-Maḫlūqāt 212 II. The Rūḥu’l-Ervāḥ and the Man-World 224 III. Malḥama and Esoteric Revelation 230 Conclusion 235 CONCLUSION 241 APPENDIX I: REASSESSING THE AUTHORSHIP OF THE DÜRR-İ MEKNŪN 248 I. -

16437189.Pdf

! ii ABSTRACT! The Making of a Sufi Order Between Heresy and Legitimacy: Bayrami-Mal!mis in the Ottoman Empire by F. Betul Yavuz Revolutionary currents with transformative ideals were part of Sufi religious identity during the late medieval Islamic period. This dissertation tries to elucidate this phenomenon by focusing on the historical evolution of the Bayrami-Mal!mi Sufi order within the Ottoman Empire. The scope of the study extends from the beginnings of the order during the ninth/fifteenth century until its partial demise by the end of the eleventh/seventeenth century. The Bayrami-Mal!miyya was marked by a reaction towards the established Sufi rituals of the time: adherents refused to wear Sufi clothes, take part in gatherings of remembrance of God, or rely upon imperial endowments for their livelihood. I suggest they carried some of the distinguishing signs of religiosity of the anarchic period between the Mongol attacks and the rise of the powerful Islamic Empires. Many local forms of Sufism had emerged, tied to charismatic, independent communities quite prevalent and powerful in their own domains. They often held particular visions regarding the saint, whose persona came to be defined in terms exceeding that of a spiritual master, often as a community elder or universal savior. Inspired by this period, Bayrami-Mal!mis reconstructed their teachings and affiliations as the social and political conditions shifted in Anatolia. While several p!rs were executed for heresy and messianic claims in the sixteenth century, the Order was able to put together a more prudent vision based on the writings of Ibn !Arabi (d. -

'I Was a Hidden Treasure'. Some Notes on A

‘I WAS A HIDDEN TREASURE’. SOME NOTES ON A COMMENTARY ASCRIBED TO MULLĀ ADRĀ SHĪRĀZĪ: SHAR ADĪTH: ‘KUNTU KANZAN MAKHFIYYAN . .’ Armin Eschraghi adr al-Dīn Muammad ibn Ibrāhīm Shīrāzī (d. 1640), better known as ‘adr al-Mutaallihīn’ or ‘Mullā adrā’, is generally considered one of the most popular and influential thinkers of Shiite Islam.1 It is often claimed that after him the philosophical tradition of Islam ceased to produce anything original. The larger part of adrā’s voluminous oeuvre is published. His major works are available in many editions and have been commented upon. However, there are also a certain number of lesser known pieces, one of them a short commentary on a celebrated adīth qudsī. The text has been published in a compilation of philosophi- cal treatises as part of a longer collection of fawāid.2 adrā’s actual authorship of it is not certain. In the introduction to his edition Ifahānī explains that it has at times also been ascribed to Muyī al-Dīn ibn al-Arabī and Alā al-Dawla Simnānī, although, he states, it is mostly found in manuscript collections of works belong- ing or ascribed to Mullā adrā. He is reluctant to judge the matter conclusively but believes that the fact that this commentary is part of a longer collection of fawāid, which contains internal evidence of adrā’s authorship, ‘strengthens probability of its belonging to adrā.’3 Whether or not its style and contents conform to adrā’s other writings needs to be decided by experts who have intimate knowledge of his works. -

Unraveling the Mystery of the Hidden Treasure

Unraveling the Mystery of The Hidden Treasure : The Origin and Development of a îad¥th Quds¥ and its Application in S´f¥ Doctrine By Moeen Afnani A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Hamid Algar, Chair Dr. John Hayes Professor Munis Faruqui Spring 2011 Abstract Unraveling the Mystery of The Hidden Treasure : The Origin and Development of a îad¥th Quds¥ and its Application in S´f¥ Doctrine by Moeen Afnani Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Hamid Algar, Chair The tradition of the Hidden Treasure is the most widely used úad¥th in the field of speculative mysticism. It states: “I was a Hidden Treasure; I loved to be known, so I created the creation in order to be known.” From the 5th /12 th century onward this tradition has occurred in major ê´f¥ texts, and the great ê´f¥ masters like Ibn al-ÔArab¥ and R´m¥ have made abundant use of it to build their mystical philosophy. Although it is very brief, this tradition refers to such themes as wuj´d (being), God as the Absolute Being, names and attributes of God, the self-disclosure of God, love as the motive for creation, the concept and process of creation, and the concept of knowledge. These themes are among the most fundamental concepts in speculative mysticism. Aside from ê´f¥s, Islamic philosophers and theologians also have mentioned this tradition in their writings.