Annual Report>> the Rockefeller Foundation 2005 Annual Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steve Harley Lee Nelson

SPARKLING ARTS EVENTS IN THE HEART OF SHOREHAM SEPT – DEC 2014 BAKA BEYOND LUNASA THE INNER VISION ORCHESTRA STEVE HARLEY GEORGIE FAME LEE NELSON TOYAH WILLCOX CURVED AIR SHAKATAK ROPETACKLECENTRE.CO.UK SEPT 2014 ropetacklecentre.co.uk BOX OFFICE: 01273 464440 SEPT 2014 WELCOME TO ROPETACKLE From music, comedy, theatre, talks, family events, exhibitions, and much more, we’ve something for everybody to enjoy this autumn and winter. As a charitable trust staffed almost entirely by volunteers, nothing comes close to the friendly atmosphere, intimate performance space, and first- class programming that makes Ropetackle one of the South Coast’s most prominent and celebrated arts venues. We believe engagement with the arts is of vital importance to the wellbeing of both individuals and the community, and with such an exciting and eclectic programme ahead of us, we’ll let the events speak for themselves. See you at the bar! THUNKSHOP THURSDAY SUPPERS BOX OFFICE: 01273 464440 Our in-house cafe Thunkshop will be serving delicious pre-show suppers from 6pm before most of our Thursday events. Advance With support from booking is recommended but not essential, please contact Sarah on 07957 166092 for further details and to book. Seats are reserved for people dining. Look out for the Thunkshop icon throughout the programme or visit page 58 for the full list of pre-show meals. Programme design by Door 22 Creative www.door22.co.uk @ropetackleart Ropetackle Arts Centre Opera Rock Folk Family Blues Spoken Word Jazz 2 SEPT 2014 ropetacklecentre.co.uk BOX OFFICE: 01273 464440 SEPT 2014 SARA SPADE & THE NOISY BOYS Sara Spade & The Noisy Boys: World War One Centenary Concert She’s back! After a sell-out Ropetackle show in January, Sara Spade & The Noisy Boys return with flapper classics like ‘Five Foot Two, Eyes of Blue’ and other popular Charlestons, plus favourite Great War-era songs including Pack up your Troubles in your Old Kit Bag and Long Way to Tipperary. -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

Dave Brubeck's Definitive “Jazzanians”

Journal of Jazz Studies vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 53-93 (Summer 2013) Dave Brubeck’s Definitive “Jazzanians” Vasil Cvetkov On December 5, 2012, American contemporary music lost one of its most important personalities—pianist and composer Dave Brubeck, who died one day before his 92nd birthday. His death marks the passing of one of the most creative and versatile musicians in American history. Widely known as an innovative jazz musician, Brubeck’s skills in writing and arranging music for classical ensembles went far beyond jazz traditions, making him a subject of interest and investigation for contemporary music researchers. He became an emblematic figure for those, who, like me, received a classical music upbringing and became fascinated by his ability to fuse jazz and classical sources into the specific style that eventually became his trademark. Despite having received a classical education, I have always been attracted by the jazz sound, so that discovering and demonstrating the plenitude of Brubeck's legacy became a natural research goal in my graduate studies. In planning this personal tribute to the late Dave Brubeck, I came to the conclusion that, perhaps, the most eloquent examples of his unique compositional style could be demonstrated around the story of a little tetrachord. Throughout a period of 17 years (1987-2003), it inspired Brubeck to create five important compositions and came to be known, by those who love Brubeck's music, as the “Jazzanians tetrachord.” The compositions varied in form, covering the full spectrum of jazz, classical, and fusion styles. I call these compositions “realizations.” Trying to trace Brubeck’s realizations chronologically through that 17- year period, I first examined published scores but discovered that there were mysterious gaps. -

Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin

Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin To cite this version: Denis-Constant Martin. Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa. African Minds, Somerset West, pp.472, 2013, 9781920489823. halshs-00875502 HAL Id: halshs-00875502 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00875502 Submitted on 25 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Sounding the Cape Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin AFRICAN MINDS Published by African Minds 4 Eccleston Place, Somerset West, 7130, South Africa [email protected] www.africanminds.co.za 2013 African Minds ISBN: 978-1-920489-82-3 The text publication is available as a PDF on www.africanminds.co.za and other websites under a Creative Commons licence that allows copying and distributing the publication, as long as it is attributed to African Minds and used for noncommercial, educational or public policy purposes. The illustrations are subject to copyright as indicated below. Photograph page iv © Denis-Constant -

BRUBECK COLLECTION SERIES 5: VIDEO and FILM (Many Recording Have Multiple Shows with Various Dates)

HOLT ATHERTON SPECIAL COLLECTIONS MS4: BRUBECK COLLECTION SERIES 5: VIDEO AND FILM (many recording have multiple shows with various dates) SUBSERIES A: Appearances (on VHS or DVD) Box 1: 1937-1961 “Round up at the Grant Ranch [in Ione]” [1937] silent (also available on film in subseries F) “Lake Tahoe 41” 1941 silent “A brief history of Dave Brubeck” 1990 (includes very short clips from circa 1950- 1987) “Stompin’ for Milli” color [1954] “A Visit with Darius Milhaud” 1955 “March of Dimes 1956” Ed Sullivan Show 1955, 1960, 1962 Subject is Jazz 1958, Subject is Jazz 1979, Ellington is Forever 1968, Dave Brubeck c.1980 Jam Session, Stars of Jazz 1958, Dave Brubeck on Ed Sullivan Show 1962, Belgium TV 1965 DBQ in Rome Italy 1959 Darius on “I’ve Got a Secret” Dave, Dari, Chris, and Dan—Tonight Show ’78, October 16, 1960 Ed Sullivan Show with Mort Sahl, Johnny Mathis, Peggy lee, and the Limeliters “Dave Brubeck #19, Sony Music Studios Columbia Jazz” [1961] “Dave Brubeck: Five Rare Ones” Jazz of Brubeck with Walter Cronkite 1961, Playboy After Dark with Hugh Hefner [1961], Jazz Casual with Ralph Gleason 1961, Look Up and Live no date, All-Star Swing Festival 1972 Dave Brubeck Quartet at Playboy Club, Chicago 1961 “Warren Taylor Tape” “All Night Long” 1961, Best of Carson 1983, Kennedy Center Tonight 1981 “Ralph Gleason’s Jazz Casual: Dave Brubeck featuring Paul Desmond” October 17, 1961 “Piano Legends” 1961, “Timex All-Star Swing Festival” 1972 Box 2: 1962-1975 “All Night Long” (movie that includes clips of Brubeck solos) 1962 “The Dave Brubeck Craven Filter Special” with Laurie Loman Australian TV 1962 “Warren Taylor Tape” Snowbird 1980, Newport 1978, Bravo Jazz Festival 1982, Dave Brubeck 1963 BBC-TV Special June 9, 1964 “Dave Brubeck Live in ’64 & ‘66” Live concerts from Belgium 1964 and Germany 1966 “Brubeck Video Scrapbook” BBC 1964, 1966, Jazz of Dave Brubeck no date, Playboy after dark [1961], 1972, Silver Anniversary tour 1976, Tonight Show 1978, Tonight Show 1982, Tonight Show 1983, Today 1990 WENH-TV St. -

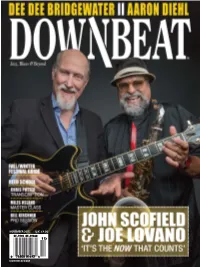

Downbeat.Com November 2015 U.K. £4.00

NOVEMBER 2015 2015 NOVEMBER U.K. £4.00 DOWNBEAT.COM DOWNBEAT JOHN SCOFIELD « DEE DEE BRIDGEWATER « AARON DIEHL « ERIK FRIEDLANDER « FALL/WINTER FESTIVAL GUIDE NOVEMBER 2015 NOVEMBER 2015 VOLUME 82 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ĺDQHWDÎXQWRY£ Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Stephen Hall Editorial Intern Baxter Barrowcliff ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sam Horn 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; -

Petworth Festival 2018

PETWORTH FESTIVAL 2018 40TH ANNIVERSARY Tuesday 17 July – Saturday 4 August Box Office 01798 344 576 and at www.petworthfestival.org.uk Box Office open from 10 May The Leconfield Estates www.leconfieldestates.co.uk The Leconfield Estates is very pleased to be the principal sponsor again in 2018 and to have sponsored the Petworth Festival for each of its 40 years. Visit our website for information about activities on the Estates which include let properties and peaceful fly fishing on the River Rother & the lakes at Petworth, and also on the Derwent, an excellent salmon river in Cumbria. PETWORTH FESTIVAL 2018 40TH ANNIVERSARY Welcome to the 2018 Petworth Festival elcome festivals; performances that doff the cap to to the the major anniversary that is the conclusion W2018 of the First World War; and ‘Open Door’ Petworth - a series of events focusing on young Festival – the and emerging performers or which are 40th anniversary specifically aimed at the younger and family Festival, and audience. All four strands reflect the best of one with a the last 40 years, but never have we quite programme pushed the boat out in this way. Please see to match and page 3 of this brochure for the full lists of the salute the major events in the four strands. milestone. There are so many There are events in ten venues and we reasons to hope cover classical and world music, jazz, you will be able comedy, theatre and the visual arts, and to join us this year not least our ‘significant’ with the Bignor Park Alive! event we hope to anniversary, but also because we have put draw in the widest family audience for what together a programme of immense variety should prove to be a real treat with events and extraordinary notoriety. -

Brubeck Brochure.La.Indd

BRUBECK2016 FESTIVAL MEMPHIS TENNESSEE APRIL 8-10 WELCOME to the 2016 Brubeck Festival, in Memphis Tennessee! ave Brubeck was a leading figure in jazz music, as an innovative, This festival is made possible by many contributors and participants: Rhodes phenomenal jazz pianist. What is sometimes forgotten is that he was also College and its nationally accredited Department of Music (NASM), the Mike Dprolific in “classical” composition, wrote a jazz musical, orchestral works, Curb Institute for Music at Rhodes, The Brubeck Institute at The University of and was a respected leader in the struggle for civil rights. The 2016 Brubeck the Pacific, the National Civil Rights Museum, Shelby County Schools, Opera Festival highlights all of these aspects of his life and work. Memphis, Playhouse on the Square, and the Memphis Symphony Orchestra. It is a privilege to be able to host the 2016 Brubeck Festival and I am grateful for all of the participant’s contributions. Special thanks must go to Darius Brubeck, Tommie Pardue and to Simon Rowe, Executive Director of the “Every individual should be expressing themselves, Brubeck Institute, without whose inspiration and support this festival would whether a politician or a minister or a policeman. not be possible. There’s a way of playing safe, and there’s a way I like to play which is where you’re going to William Skoog, Chair Department of Music take a chance on making mistakes in order to create Rhodes College something you haven’t created before.” –Dave Brubeck Please dive deeply into the During his lifetime Dave received a number of prestigious awards and honorary life, times, and diverse music doctorate degrees, he was a 2009 Kennedy Center Honoree, and was declared a of Dave Brubeck during this “Living Legend” by the U. -

Bellagio Center Voices and Visions

The Rockefeller Foundation invited former Bellagio conference participants and residents—from scientists, economists, and leaders of non-governmental organiza- tions to composers, painters, and authors—to share their memories of and perspectives on their time at the Center, including its impact on their work. Each of these essays begins with biographical details about the contributor, the year(s) of his or her Bellagio visit(s), and the project(s) the contributor was working on there. Some are illustrated Voices and with artwork created at Bellagio. Visions 56 57 Pilar Palaciá Introduction Managing Director, the Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio Center I have often wondered how I could explain what makes Bellagio Or perhaps I should focus on the historical treasures of the such a special place. I could say it is the visiting residents and confer- property: the main Villa, built in 1540, providing a dignified scenario ence participants themselves, the people I have met during my time for special dinners; the Sfondrata, constructed at the end of the 16th here, and their remarkable, diverse projects. The Center hosts people century, offering a place for quiet contemplation by the lake and, from all over the world who are seriously trying to make a differ- with its tranquil beauty, motivating guests to move beyond their own ence, who fight for equity and justice, who are passionate about their expectations and limitations in their work; the Frati, originally built creativity, whose actions are examples to others. Dedicated artists, as a Capuchin monastery in 1610, its austere and intimate nature policymakers, scholars, practitioners, and scientists all come together conveying an unmatched sense of connectedness and shared respon- at Bellagio, creating an exhilarating atmosphere. -

The Guardian, November 14, 1974

Wright State University CORE Scholar The Guardian Student Newspaper Student Activities 11-14-1974 The Guardian, November 14, 1974 Wright State University Student Body Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/guardian Part of the Mass Communication Commons Repository Citation Wright State University Student Body (1974). The Guardian, November 14, 1974. : Wright State University. This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Activities at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Guardian Student Newspaper by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. November 14, 1974 Vol 11. Issue 20 Wright State University GUARDIAN Washington Week enthralls audience by Samuel Latham Washington Week in Review, the top rated show on PBS, visited Wright State Sunday- night. It was the first time for thr show, part of the Artist and Lecture Series, to visit a college campus. Four of the nation's leading jjournalists. Paul Duke of SBC news. Peter Lisa go r of the Chicago Daily Sews Times. Neil Macneii and Charles. Cordray of the Baltimore Sun comprise a panel that discusses the latest news items and happenings in Washington and around the world every week. For approximately 30 minutes the journalists discussed their Final exam schedule p 8 views on a number of topics of national concern, and the first I to r Charles Cordray, Neil Macneii, Peter Lisagor, Paul Duke, from Washington Week in Review topic was the results of ihe recent election. Mscneil said that the Congress which was "slightly conservative, WSU traffic violators may end up in court has now become sliyhtly liberal," but that it is only by Nathan Schwartz advanced courses in the i Ken Davenport, Associate a SiO fine which Holloway can "philosophically liberal. -

WORLD CONFERENCE AGAINST RACISM, RACIAL DISCRIMINATION, XENOPHOBIA and RELATED INTOLERANCE Durban, South Africa 31 August -7 September 2001

JOURNAL of the WORLD CONFERENCE AGAINST RACISM, RACIAL DISCRIMINATION, XENOPHOBIA AND RELATED INTOLERANCE Durban, South Africa 31 August -7 September 2001 No. 8 PROGRAMME OF MEETINGS Friday, 7 September 2001 9:00 - 10:00 a.m. General Committee (closed) Room 5 9:15 – 9:45 a.m. Cultural event presented by the Department Plenary Hall of Arts, Culture, Science and Technology of the Government of the Republic of South Africa (see Announcements, p.10) Plenary 10:00 a.m. - 1:00 p.m. 19th meeting Plenary Hall Conference themes [9]: - Sources, causes, forms and contemporary manifestations of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance - Victims of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance - Measures of prevention, education and protection aimed at the eradication of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance at the national, regional and international levels - Provision of effective remedies, recourse, redress, compensatory * and other measures at the national, regional and international levels DUR.01-083 2 - Strategies to achieve full and effective equality, including international cooperation and enhancement of United Nations and other international mechanisms in combating racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance, and follow-up (A/CONF/189/9; A/CONF/189/10 and Add. 1-8) * The use of the word “compensatory” is without prejudice to any outcome of this conference. (Note: Speakers 1-53 are carried over from Wednesday, 5 September 2001) 1. African and African Descent Women’s Caucus 2. Service Peace and Justice in Latin America 3. Asian Indigenous & Tribal Peoples Network (India) 4. The 1990 Trust (United Kingdom) 5. American Psychological Association 6. -

Global Governance and the Emergence of Global Institutions for the 21 St Century

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 71.178.53.58, on 20 Jan 2020 at 19:24:33, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/AF7D40B152C4CBEDB310EC5F40866A59 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 71.178.53.58, on 20 Jan 2020 at 19:24:33, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/AF7D40B152C4CBEDB310EC5F40866A59 “In this outstanding volume, López-Claros, Dahl, and Groff document the existen- tial challenges facing our global institutions, from environmental decline and the failure of existing international security mechanisms to mass population flows and the crisis of sovereignty and civil society engagement. The resulting landscape might seem hopeless and overwhelming, if not for the authors’ innovative, wide-ranging, and thought-provoking recommendations for reshaping existing insti- tutions to expand their relevance and effectiveness. Their ideas for updating our seven-decades-old structures include creating an international peace force, ratifying a United Nations Bill of Rights, reforming the UN Security Council and Inter- national Monetary Fund, establishing a civil society chamber, and beyond. Readers may not endorse every one of their suggestions, but they are invited into a fascinat- ing game of ‘what if?’ and ‘why not?’ It is an invitation that should not be missed.” Ambassador Donald Steinberg, Board member, Center for Strategic and International Studies “The current UN-based world system of governance, largely formulated in the mid-20th century after the Second World War, is not up to dealing satisfactorily with 21st-century problems.