Polybius and His Legacy. (= Trends in Classics - Supplementary Volumes, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Royal Power, Law and Justice in Ancient Macedonia Joseph Roisman

Royal Power, Law and Justice in Ancient Macedonia Joseph Roisman In his speech On the Crown Demosthenes often lionizes himself by suggesting that his actions and policy required him to overcome insurmountable obstacles. Thus he contrasts Athens’ weakness around 346 B.C.E. with Macedonia’s strength, and Philip’s II unlimited power with the more constrained and cumbersome decision-making process at home, before asserting that in spite of these difficulties he succeeded in forging later a large Greek coalition to confront Philip in the battle of Chaeronea (Dem.18.234–37). [F]irst, he (Philip) ruled in his own person as full sovereign over subservient people, which is the most important factor of all in waging war . he was flush with money, and he did whatever he wished. He did not announce his intentions in official decrees, did not deliberate in public, was not hauled into the courts by sycophants, was not prosecuted for moving illegal proposals, was not accountable to anyone. In short, he was ruler, commander, in control of everything.1 For his depiction of Philip’s authority Demosthenes looks less to Macedonia than to Athens, because what makes the king powerful in his speech is his freedom from democratic checks. Nevertheless, his observations on the Macedonian royal power is more informative and helpful than Aristotle’s references to it in his Politics, though modern historians tend to privilege the philosopher for what he says or even does not say on the subject. Aristotle’s seldom mentions Macedonian kings, and when he does it is for limited, exemplary purposes, lumping them with other kings who came to power through benefaction and public service, or who were assassinated by men they had insulted.2 Moreover, according to Aristotle, the extreme of tyranny is distinguished from ideal kingship (pambasilea) by the fact that tyranny is a government that is not called to account. -

Anton Powell, Nicolas Richer (Eds.), Xenophon and Sparta, the Classical Press of Wales, Swansea 2020, 378 Pp.; ISBN 978-1-910589-74-8

ELECTRUM * Vol. 27 (2020): 213–216 doi:10.4467/20800909EL.20.011.12801 www.ejournals.eu/electrum Anton Powell, Nicolas Richer (eds.), Xenophon and Sparta, The Classical Press of Wales, Swansea 2020, 378 pp.; ISBN 978-1-910589-74-8 The reviewed book is a collection of twelve papers, previously presented at the confe- rence organised by École Normale Supérieure in Lyon in 2006. According to the edi- tors, this is a first volume in the planned series dealing with sources of Spartan his- tory. The books that follow this will deal with the presence of this topic in works by Thucydides, Herodotus, Plutarch, and in archaeological material. The decision to start the cycle from Xenophon cannot be considered as surprising; this ancient author has not only written about Sparta, but also had opportunities to visit the country, person- ally met a number of its officials (including king Agesilaus), and even sent his own sons for a Spartan upbringing. Thus his writings are widely considered as our best source to the history of Sparta in the classical age. Despite this, Xenophon’s literary work remains the subject of numerous controver- sies in discussions among modern scholars. The question of his objectivity is especial- ly problematic and the views about the strong partisanship of Xenophon prevailed for a long time; allegedly, he was depicting Sparta and king Agesilaus in a possibly overly positive light, even omitting inconvenient information.1 In the second half of the 20th century such opinion has been met with a convincing polemic, clearly seen in the works of H. -

Citations in Classics and Ancient History

Citations in Classics and Ancient History The most common style in use in the field of Classical Studies is the author-date style, also known as Chicago 2, but MLA is also quite common and perfectly acceptable. Quick guides for each of MLA and Chicago 2 are readily available as PDF downloads. The Chicago Manual of Style Online offers a guide on their web-page: http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/tools_citationguide.html The Modern Language Association (MLA) does not, but many educational institutions post an MLA guide for free access. While a specific citation style should be followed carefully, none take into account the specific practices of Classical Studies. They are all (Chicago, MLA and others) perfectly suitable for citing most resources, but should not be followed for citing ancient Greek and Latin primary source material, including primary sources in translation. Citing Primary Sources: Every ancient text has its own unique system for locating content by numbers. For example, Homer's Iliad is divided into 24 Books (what we might now call chapters) and the lines of each Book are numbered from line 1. Herodotus' Histories is divided into nine Books and each of these Books is divided into Chapters and each chapter into line numbers. The purpose of such a system is that the Iliad, or any primary source, can be cited in any language and from any publication and always refer to the same passage. That is why we do not cite Herodotus page 66. Page 66 in what publication, in what edition? Very early in your textbook, Apodexis Historia, a passage from Herodotus is reproduced. -

Polybius: the Histories Translated by W

Polybius: The Histories Translated by W. R. Paton From BOOK ONE own existence. The Lacedaemonians, after AD previous chroniclers neglected to having for many years disputed the hegemony speak in praise of History in general, of Greece, at length attained it but to hold it H it might perhaps have been necessary uncontested for scarce twelve years. The for me to recommend everyone to choose for Macedonian rule in Europe extended but from study and welcome such treatises as the the Adriatic to the Danube, which would present, since there is no more ready appear a quite insignificant portion of the corrective of conduct than knowledge of the continent. Subsequently, by overthrowing the past. But all historians, one may say without Persian empire they became supreme in Asia exception, and in no half-hearted manner, but also. But though their empire was now making this the beginning and end of their regarded as the greatest in extent and power labor, have impressed on us that the soundest that had ever existed, they left the larger part education and training for a life of active of the inhabited world as yet outside it. For politics is the study of History, and that the they never even made a single attempt on surest and indeed the only method of learning Sicily, Sardinia, or Africa, and the most how to bear bravely the vicissitudes of warlike nations of Western Europe were, to fortune, is to recall the calamities of others. speak the simple truth, unknown to them. But Evidently therefore one, and least of all the Romans have subjected to their rule not myself, would think it his duty at this day to portions, but nearly the whole of the world, repeat what has been so well and so often said. -

Contesting the Greatness of Alexander the Great: the Representation of Alexander in the Histories of Polybius and Livy

ABSTRACT Title of Document: CONTESTING THE GREATNESS OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT: THE REPRESENTATION OF ALEXANDER IN THE HISTORIES OF POLYBIUS AND LIVY Nikolaus Leo Overtoom, Master of Arts, 2011 Directed By: Professor Arthur M. Eckstein, Department of History By investigating the works of Polybius and Livy, we can discuss an important aspect of the impact of Alexander upon the reputation and image of Rome. Because of the subject of their histories and the political atmosphere in which they were writing - these authors, despite their generally positive opinions of Alexander, ultimately created scenarios where they portrayed the Romans as superior to the Macedonian king. This study has five primary goals: to produce a commentary on the various Alexander passages found in Polybius’ and Livy’s histories; to establish the generally positive opinion of Alexander held by these two writers; to illustrate that a noticeable theme of their works is the ongoing comparison between Alexander and Rome; to demonstrate Polybius’ and Livy’s belief in Roman superiority, even over Alexander; and finally to create an understanding of how this motif influences their greater narratives and alters our appreciation of their works. CONTESTING THE GREATNESS OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT: THE REPRESENTATION OF ALEXANDER IN THE HISTORIES OF POLYBIUS AND LIVY By Nikolaus Leo Overtoom Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2011 Advisory Committee: Professor Arthur M. Eckstein, Chair Professor Judith P. Hallett Professor Kenneth G. Holum © Copyright by Nikolaus Leo Overtoom 2011 Dedication in amorem matris Janet L. -

Xenophon's Theory of Moral Education Ix

Xenophon’s Theory of Moral Education Xenophon’s Theory of Moral Education By Houliang Lu Xenophon’s Theory of Moral Education By Houliang Lu This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Houliang Lu All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-6880-9 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-6880-8 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ................................................................................... vii Editions ..................................................................................................... viii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Part I: Background of Xenophon’s Thought on Moral Education Chapter One ............................................................................................... 13 Xenophon’s View of His Time Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 41 Influence of Socrates on Xenophon’s Thought on Moral Education Part II: A Systematic Theory of Moral Education from a Social Perspective Chapter One .............................................................................................. -

Epicurus' Kupia L\6~A XVII

Epicurus' "Kyria Doxa" [Greek] XVII Clay, Diskin Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Spring 1972; 13, 1; ProQuest pg. 59 Epicurus' Kupia L\6~a XVII Diskin Clay N 1888 Usener published a collection of sayings Karl Wotke had I discovered in the Vatican with the title 'EmKovpov IIpocc/)(j)VT]CLc the 'Pronouncement of Epicurus'. In all, this new gnomologium contained some 81 pronouncements, twelve of which had been long familiar from Diogenes Laertius. The rest, except those which were already known as the pronouncements of Metrodorus, were new; or new in their Greek originaP The new Vatican collection irritated sores surrounding the ques tion of the genesis and authenticity of the KVpUXL L16gaL which Usener had opened a year before.2 But some of the new sayings were in fact the pronouncements of Epicurus, and they allowed a better apprecia tion of the care Epicurus took in refining the language of his moral teaching to its sharpest point. One of the new sayings (Sententia Vati cana 68) Usener spotted as the reformulation of one of Epicurus' gno mai known in its earlier form from Aelian and Stobaeus.3 The saying they knew as: l' '\1 'f I '\\\ I ,~\ t I CtJ O"LYOV OVx LKavov. al\l\a TOVTCtJ yE OVOEV LKaVOV was apparently not neat enough for Epicurus. If Usener is right, he reduced his thought to the curt and elegant , ~'f , 1" '\' ,~ I OVoEV LKavOV CtJ O"LYOV TO LKavov -"nothing is enough for the man for whom little is enough." Another of the new sayings from the Vatican made it clear that Epicurus not only went to pains to reformulate his own language, but that of others. -

The Relationship Between the Western Satraps and the Greeks

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2018-11-08 East Looking West: the Relationship between the Western Satraps and the Greeks Ward, Megan Leigh Falconer Ward, M. L. F. (2018). East Looking West: the Relationship between the Western Satraps and the Greeks (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/33255 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/109170 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY “East Looking West: the Relationship between the Western Satraps and the Greeks.” by Megan Leigh Falconer Ward A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN GREEK AND ROMAN STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA NOVEMBER, 2018 © Megan Leigh Falconer Ward 2018 Abstract The satraps of Persia played a significant role in many affairs of the European Greek poleis. This dissertation contains a discussion of the ways in which the Persians treated the Hellenic states like subjects of the Persian empire, particularly following the expulsion of the Persian Invasion in 479 BCE. Chapter One looks at Persian authority both within the empire and among the Greeks. -

Epicurus on Socrates in Love, According to Maximus of Tyre Ágora

Ágora. Estudos Clássicos em debate ISSN: 0874-5498 [email protected] Universidade de Aveiro Portugal CAMPOS DAROCA, F. JAVIER Nothing to be learnt from Socrates? Epicurus on Socrates in love, according to Maximus of Tyre Ágora. Estudos Clássicos em debate, núm. 18, 2016, pp. 99-119 Universidade de Aveiro Aveiro, Portugal Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=321046070005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Nothing to be learnt from Socrates? Epicurus on Socrates in love, according to Maximus of Tyre Não há nada a aprender com Sócrates? Epicuro e os amores de Sócrates, segundo Máximo de Tiro F. JAVIER CAMPOS DAROCA (University of Almería — Spain) 1 Abstract: In the 32nd Oration “On Pleasure”, by Maximus of Tyre, a defence of hedonism is presented in which Epicurus himself comes out in person to speak in favour of pleasure. In this defence, Socrates’ love affairs are recalled as an instance of virtuous behaviour allied with pleasure. In this paper we will explore this rather strange Epicurean portrayal of Socrates as a positive example. We contend that in order to understand this depiction of Socrates as a virtuous lover, some previous trends in Platonism should be taken into account, chiefly those which kept the relationship with the Hellenistic Academia alive. Special mention is made of Favorinus of Arelate, not as the source of the contents in the oration, but as the author closest to Maximus both for his interest in Socrates and his rhetorical (as well as dialectical) ways in philosophy. -

Polybios, the Laws of War, and Philip V of Macedon1

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE Polybios, the Laws of War, and Philip V of Macedon AUTHORS Nicholson, EL JOURNAL Historia - Zeitschrift fur Alte Geschichte DEPOSITED IN ORE 25 September 2018 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10871/34104 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication Historia 67, 2018/4, 434–453 DOI 10.25162/historia-2018-0017 Emma Nicholson Polybios, the Laws of War, and Philip V of Macedon1 Abstract: In his account of Philip V of Macedon’s attack of Thermos in 218 BC (5.9–12), Poly- bios uses the ‘laws of war’ as a rhetorical device to reinforce his own interpretation of the king and perspective on the situation. While this is not the only place within his work where the laws are referenced in such a way – they are, for instance, similarly used in the defence of Achaian actions after recapturing Mantinea in 226 BC (Plb. 2.58) – the Thermos episode represents the most extensive and explicit application of this motif and therefore offers us an opportunity to investigate the historian’s historiographical aims and literary workings in more detail. This arti- cle sets out to offer fresh perspectives on this well-known episode, exploring how the reference to the ‘laws’ has serious consequences for the development of the king’s character within the narrative, how it engages with wider didactic and political purposes, and what it reveals about Polybios’ historical method and literary workings. -

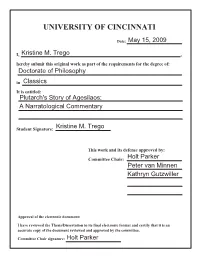

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 15, 2009 I, Kristine M. Trego , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctorate of Philosophy in Classics It is entitled: Plutarch's Story of Agesilaos; A Narratological Commentary Student Signature: Kristine M. Trego This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Holt Parker Peter van Minnen Kathryn Gutzwiller Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Holt Parker Plutarch’s Story of Agesilaos; A Narratological Commentary A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of Classics of the College of Arts and Sciences 2009 by Kristine M. Trego B.A., University of South Florida, 2001 M.A. University of Cincinnati, 2004 Committee Chair: Holt N. Parker Committee Members: Peter van Minnen Kathryn J. Gutzwiller Abstract This analysis will look at the narration and structure of Plutarch’s Agesilaos. The project will offer insight into the methods by which the narrator constructs and presents the story of the life of a well-known historical figure and how his narrative techniques effects his reliability as a historical source. There is an abundance of exceptional recent studies on Plutarch’s interaction with and place within the historical tradition, his literary and philosophical influences, the role of morals in his Lives, and his use of source material, however there has been little scholarly focus—but much interest—in the examination of how Plutarch constructs his narratives to tell the stories they do. -

The World According to Polybius by Mark Herman

C3i Magazine Nr.1 (1992) The World According to Polybius by Mark Herman Gibbon wrote about the fall of the Roman Empire; Polybius witnessed its rise. The burning question at the beginning of the third century BC was, “why Rome?” Who were these Romans, and how did they become the preeminent Mediterranean power? Our most recent “Great Battles of History” game, “S.P.Q.R.”, covers many of the critical battles that led to Rome’s ascendency over the ancient Mediterranean. My purpose in this article is to place the game in relation to the key events that led to the longest continuous political system in the history of the world, and like Polybius, come to some conclusions on why it happened. In 321 BC Rome was defeated by the Samnites in the battle of Caudine Forks, Alexander the Great had been dead for two years, and the empire he had conquered was in disarray -- as his generals fought for the right to be one of his successors, or Diadocchi. By this year Alexander’s empire had begun to fragment into five major powers; whose attention would remain diverted from the developing situation on the Tiber -- until it was to late. Under Seleucus, Alexander’s general, the Eastern part of the empire formed, centered on Babylonia (modern Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan). Ptolemy became Pharaoh in Egypt and controlled one of the key granaries of the Mediterranean. Antigonus controlled Asia Minor, and Coele Syria (modern Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, and Israel). Lysimachus controlled Thrace, while Cassander controlled Macedonia proper. Greece continued to consist of independent city states dominated by Macedonia, although the Achean league was forming in the Peloponnesus.