Feasting in the Land of the Dawn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Odyssey, Part 1: the Adventures of Odysseus

from The Odyssey, Part 1: The Adventures of Odysseus Homer, translated by Robert Fitzgerald ANCHOR TEXT | EPIC POEM Archivart/Alamy Stock Photo Archivart/Alamy This version of the selection alternates original text The poet, Homer, begins his epic by asking a Muse1 to help him tell the story of with summarized passages. Odysseus. Odysseus, Homer says, is famous for fighting in the Trojan War and for Dotted lines appear next to surviving a difficult journey home from Troy.2 Odysseus saw many places and met many the summarized passages. people in his travels. He tried to return his shipmates safely to their families, but they 3 made the mistake of killing the cattle of Helios, for which they paid with their lives. NOTES Homer once again asks the Muse to help him tell the tale. The next section of the poem takes place 10 years after the Trojan War. Odysseus arrives in an island kingdom called Phaeacia, which is ruled by Alcinous. Alcinous asks Odysseus to tell him the story of his travels. I am Laertes’4 son, Odysseus. Men hold me formidable for guile5 in peace and war: this fame has gone abroad to the sky’s rim. My home is on the peaked sea-mark of Ithaca6 under Mount Neion’s wind-blown robe of leaves, in sight of other islands—Dulichium, Same, wooded Zacynthus—Ithaca being most lofty in that coastal sea, and northwest, while the rest lie east and south. A rocky isle, but good for a boy’s training; I shall not see on earth a place more dear, though I have been detained long by Calypso,7 loveliest among goddesses, who held me in her smooth caves to be her heart’s delight, as Circe of Aeaea,8 the enchantress, desired me, and detained me in her hall. -

Magical Practice in the Latin West Religions in the Graeco-Roman World

Magical Practice in the Latin West Religions in the Graeco-Roman World Editors H.S. Versnel D. Frankfurter J. Hahn VOLUME 168 Magical Practice in the Latin West Papers from the International Conference held at the University of Zaragoza 30 Sept.–1 Oct. 2005 Edited by Richard L. Gordon and Francisco Marco Simón LEIDEN • BOSTON 2010 Th is book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Magical practice in the Latin West : papers from the international conference held at the University of Zaragoza, 30 Sept.–1 Oct. 2005 / edited by Richard L. Gordon and Francisco Marco Simon. p. cm. — (Religions in the Graeco-Roman world, ISSN 0927-7633 ; v. 168) Includes indexes. ISBN 978-90-04-17904-2 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Magic—Europe—History— Congresses. I. Gordon, R. L. (Richard Lindsay) II. Marco Simón, Francisco. III. Title. IV. Series. BF1591.M3444 2010 133.4’3094—dc22 2009041611 ISSN 0927-7633 ISBN 978 90 04 17904 2 Copyright 2010 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, Th e Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to Th e Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

The Cyclops in the Odyssey, Ulysses, and Asterios Polyp: How Allusions Affect Modern Narratives and Their Hypotexts

THE CYCLOPS IN THE ODYSSEY, ULYSSES, AND ASTERIOS POLYP: HOW ALLUSIONS AFFECT MODERN NARRATIVES AND THEIR HYPOTEXTS by DELLEN N. MILLER A THESIS Presented to the Department of English and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts December 2016 An Abstract of the Thesis of Dellen N. Miller for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of English to be taken December 2016 Title: The Cyclops in The Odyssey, Ulysses, and Asterios Polyp: How Allusions Affect Modern Narratives and Their Hypotexts Approved: _________________________________________ Paul Peppis The Odyssey circulates throughout Western society due to its foundation of Western literature. The epic poem thrives not only through new editions and translations but also through allusions from other works. Texts incorporate allusions to add meaning to modern narratives, but allusions also complicate the original text. By tying two stories together, allusion preserves historical works and places them in conversation with modern literature. Ulysses and Asterios Polyp demonstrate the prevalence of allusions in books and comic books. Through allusions to both Polyphemus and Odysseus, Joyce and Mazzucchelli provide new ways to read both their characters and the ancient Greek characters they allude to. ii Acknowledgements I would like to sincerely thank Professors Peppis, Fickle, and Bishop for your wonderful insight and assistance with my thesis. Thank you for your engaging courses and enthusiastic approaches to close reading literature and graphic literature. I am honored that I may discuss Ulysses and Asterios Polyp under the close reading practices you helped me develop. -

Back-To-Back Synopses.Indd

Storykit: Back-to-back Synopses Short Synopsis (in 3s!) for ease of memorisation: The Wooden Horse 1. The Greeks go to war with the Trojans. 2. Odysseus comes up with the Wooden Horse ploy. 3. The Greeks win the war. The Ciconians 1. They are brought to the Ciconian shores by a freak wind. 2. The Greeks attack them because they were allies of Troy. 3. The Ciconians attack them back and the Greeks are forced to retreat. The Lotus Eaters 1. Arrive on a wooded isle and lose a searching-garrison. 2. Go in search and find them drinking the juice of happiness and forgetting. 3. Just get away before they are all stuck on the island under the influence of the juice. The Cyclops 1. Arrive on a barren island and search it. 2. Find the home of the Cyclops and are trapped in it. 3. Odysseus (‘Nobody’) tricks his way out, blinding the Cyclops, and they just escape. http://education.worley2.continuumbooks.com © Peter Worley (2012) The If Odyseey. London: Bloomsbury Illustrations © Tamar Levi 2012 Aeolus 1. Arrive on a fortified island and are finally welcomed as guests. 2. Odysseus is given a bag as a gift by Aeolus. 3. Crew mutiny just as they reach home and release the winds from inside the bag, blowing them back out to sea. The Laestrygonians 1. Arrive on another island with an encircled harbour. 2. Find out the hard way that this is an island of giant cannibals. 3. They only just escaped with their lives. Circe 1. Arrive on yet another island only for some of the men to be turned into pigs by the goddess Circe. -

Curriculum Vitae Bonnie Maclachlan (Updated April, 2019)

Curriculum Vitae Bonnie MacLachlan (Updated April, 2019) Bonnie MacLachlan retired from the Department of Classical Studies at the University of Western Ontario in 2012. While no longer teaching in the department she continues with her research, giving conference presentations and publishing in the area of Greek poetry and religion, comic theatre in the Greek West and gender studies. In the fall of 2014 she gave graduate seminars at the Department of Classics and Anthropology at the University of Siena, on questions in Greek epistemology arising from both texts and material culture. She served as Vice-President, President and Past-President of the Classical Association of Canada from 2012-2018. In November 2018 she presented a keynote address for a conference in Lausanne, Switzerland, entitled “Non-elite Couples in Greco-Roman Antiquity.” She has submitted a written version of her talk as a chapter for a book to be published by Routledge and continues to work on aspects of this subject. The focus of another work-in- progress is the development of the concept and measurement of ‘value’ in ancient Greece. The earliest objects with quantifiable value possessed functional potential, such as cattle, tripods or obeloi. Gradually representational value shifted to objects with symbolic worth such as ingots of metal, before taking its final form with coins beginning in 6th century BCE. Lydia. On this subject she is working with a consortium of earth scientists (local and international) and anthropologists who do deep analysis of the metal content -

Radcliffe Edmonds CV 2021

Radcliffe Edmonds CV - updated June 24, 2021 RADCLIFFE G. EDMONDS III Paul Shorey Professor of Greek Department of Greek, Latin, & Classical Studies, Bryn Mawr College [email protected] https://www.brynmawr.edu/people/radcliffe-edmonds Education: University of Chicago: Classical Languages and Literatures M.A. 12/94, Ph.D. 6/99. Yale University: Bachelor of Arts, magna cum laude with distinction, 6/92. Dissertation: (Advisors: Christopher Faraone, Bruce Lincoln, Martha Nussbaum ) A Path Neither Simple Nor Single: The Use of Myth in Plato, Aristophanes, and the 'Orphic' Gold Tablets Academic Honors: Center for Hellenic Studies Fellowship, 2007-2008 Loeb Classical Library Foundation Fellowship, 2004-2005 Dissertation Fellowship, Chicago Humanities Institute, 1998-9 (now the Franke Institute for the Humanities) Junior Fellowship, Institute for the Advanced Study of Religion, 1997-8 (now the Martin Marty Center) National Endowment for the Humanities Grant, Isthmia Excavation Project, 1995 University of Chicago Century Fellowship, 1993-1997 Phi Beta Kappa, Yale University, 1991 Professional Associations: Society for Classical Studies (formerly the American Philological Association) International Plato Society Society for Biblical Literature Society for Ancient Mediterranean Religions Research and Teaching Interests: Greek mythology, religions of the ancient Greek and Roman world, ‘Orphism’ and Orphica, especially the ‘Orphic’ gold tablets, magic in the Greco-Roman world, eros in Greek culture, Greek social and intellectual history, death -

Unit 5: Epic and Myth

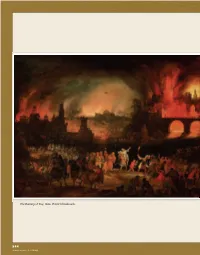

The Burning of Troy, 1606. Pieter Schoubroeck. 944 Archivo Iconografico, S.A./CORBIS UNIT FIVE Epic and Myth Looking Ahead Many centuries ago, before books, magazines, paper, and pencils were invented, people recited their stories. Some of the stories they told offered explanations of natural phenomena, such as thunder and lightning, or the culture’s customs or beliefs. Other stories were meant for entertainment. Taken together, these stories—these myths, epics, and legends—tell a history of loyalty and betrayal, heroism and cowardice, love and rejection. In this unit, you will explore the literary elements that make them unique. PREVIEW Big Ideas and Literary Focus BIG IDEA: LITERARY FOCUS: 1 Journeys Hero BIG IDEA: LITERARY FOCUS: 2 Courage and Cleverness Archetype OBJECTIVES In learning about the genres of epic and myth, • identifying and exploring literary elements you will focus on the following: significant to the genres • understanding characteristics of epics and myths • analyzing the effect that these literary elements have upon the reader 945 Genre Focus: Epic and Myth What is unique about epics and myths? Why do we read stories from the distant past? answer. He thought that in order for us to under- Why should we care about heroes and villains long stand the people we are today, we have to learn dead? About cities and palaces that were destroyed about those who came before us. One way to do centuries before our time? The noted psychologist that, Jung believed, was to read the myths and and psychiatrist Carl Jung thought he knew the epics of long ago. -

The Sea. John Banville. Knopf: New York, 2005. Paperback, 195 Pages

e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies Volume 9 Book Reviews Article 4 8-18-2006 The eS a. John Banville. Knopf: New York, 2005. Paperback, 195 pages. ISBN 0-30726- 311-8. Matthew rB own University of Massachusetts – Boston Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi Recommended Citation Brown, Matthew (2006) "The eS a. John Banville. Knopf: New York, 2005. Paperback, 195 pages. ISBN 0-30726- 311-8.," e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies: Vol. 9 , Article 4. Available at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi/vol9/iss1/4 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact open- [email protected]. The Sea. John Banville. Knopf: New York, 2005. Paperback, 195 pages. ISBN 0-30726- 311-8. $23.00. Matthew Brown, University of Massachusetts-Boston To the surprise of many, John Banville's The Sea won the 2005 Booker prize for fiction, surprising because of all of Banville's dazzlingly sophisticated novels, The Sea seems something of an afterthought, a remainder of other and better books. Everything about The Sea rings familiar to readers of Banville's oeuvre, especially its narrator, who is enthusiastically learned and sardonic and who casts weighty meditations on knowledge, identity, and art through the murk of personal tragedy. This is Max Morden, who sounds very much like Alexander Cleave from Eclipse (2000), or Victor Maskell from The Untouchable (1997). -

The Quest for God in the Novels of John Banville 1973-2005: a Postmodern Spiritualily

THE QUEST FOR GOD IN THE NOVELS OF JOHN BANVILLE 1973-2005: A POSTMODERN SPIRITUALITY Brendan McNamee Lewiston, Queenson, Lampeter: The Edwin Mellen Press. 2006 (by Violeta Delgado Crespo. Universidad de Zaragoza) [email protected] 121 As McNamee puts it in his study, it seems that “the ultimate aim of Banville’s fiction is to elude interpretation” (6). It is perhaps this elusiveness that ensures a growing number of critical contributions on the work of a writer who has explicated his aesthetic, his view of art in general, and literature in particular, in talks, interviews and varied writings. McNamee’s is the seventh monographic study of John Banville’s work published to date, and claims to differ from the previous six by widening the cultural context in which the work of the Irish writer has been read. Although, to my knowledge, John Banville has never defined himself in these terms, McNamee portrays him as an essentially religious writer (13) when he foregrounds the deep spiritual yearning that Banville’s fiction exhibits in combination with the many postmodern elements (paradox and parody, self- reflexivity, intertextuality) that are familiar in his novels. To McNamee, Banville’s enigmatic fictions allow for a link between the disparate phenomena of pre-modern mysticism and postmodernism, suggesting that many aspects of the postmodern sensibility veer toward the spiritual. He considers the language of Banville’s fiction intrinsically mystical, an artistic form of what is known as apophatic language, which he defines as “the mode of writing with which mystics attempt to say the unsayable” (170). In terms of style, Banville’s writing approaches the ineffable: that which cannot be paraphrased or described. -

“The Ghost of That Ineluctable Past”: Trauma and Memory in John Banville’S Frames Trilogy GPA: 3.9

“THE GHOST OF THAT INELUCTABLE PAST”: TRAUMA AND MEMORY IN JOHN BANVILLE’S FRAMES TRILOGY BY SCOTT JOSEPH BERRY A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS English December, 2016 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Jefferson Holdridge, PhD, Advisor Barry Maine, PhD, Chair Philip Kuberski, PhD ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To paraphrase John Banville, this finished thesis is the record of its own gestation and birth. As such, what follows represents an intensely personal, creative journey for me, one that would not have been possible without the love and support of some very important people in my life. First and foremost, I would like to thank my wonderful wife, Kelly, for all of her love, patience, and unflinching confidence in me throughout this entire process. It brings me such pride—not to mention great relief—to be able to show her this work in its completion. I would also like to thank my parents, Stephen and Cathyann Berry, for their wisdom, generosity, and support of my every endeavor. I am very grateful to Jefferson Holdridge, Omaar Hena, Mary Burgess-Smyth, and Kevin Whelan for their encouragement, mentorship, and friendship across many years of study. And to all of my Wake Forest friends and colleagues—you know who you are—thank you for your companionship on this journey. Finally, to Maeve, Nora, and Sheilagh: Daddy finally finished his book. Let’s go play. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………...iv -

Theriomorphic Forms: Analyzing Terrestrial Animal- Human Hybrids in Ancient Greek Culture and Religion

Theriomorphic Forms: Analyzing Terrestrial Animal- Human Hybrids in Ancient Greek Culture and Religion Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Carter, Caroline LynnLee Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 21:29:46 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/633185 THERIOMORPHIC FORMS: ANALYZING TERRESTRIAL ANIMAL-HUMAN HYBRIDS IN ANCIENT GREEK CULTURE AND RELIGION by Caroline Carter ____________________________ Copyright © Caroline Carter 2019 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES AND CLASSICS In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2019 THE UNIYERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Master's Committee, we certi$ that we have read the thesis prepared by Caroline Carter titled Theriomorphic Forms: Analyzing Terrestrial Animal-Humøn Hybrids in Ancíent Greek Culture and Religion and reç¡¡ü¡sr6 that it be accepted as firlfilling the disse¡tation requirement for the Master's Degree. G Date: + 26 Z¿f T MaryV o 1.011 ,AtÌ.r.ln Date: \l 41 , Dr. David Gilman Romano - 4*--l -r Date; { zé l2 Dr. David Soren r) øate:4'2 6 - l\ Dr. Kyle Mahoney Final approval and acceptance of this thesis is contingent upon the candidate's submission of the final copies of the thesis to the Graduate College. -

Tales from Greek Mythology

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. http://books.google.com 600078481Y ". By the same Author. TALES OF THE GODS AND HEROES. With 6 Landscape Illustrations engraved on Wood from Drawings by the Author. Ecp. 8vo. price 5*. AMONG the tales supplied by the vast stores of Greek legend, some are exceedingly simple in their character, while others are very complicated. In the series entitled Tales from Greek Mytho logy -, care was taken not to include any tales involving ideas which young children would not readily understand ; but most of the stories given in this volume cannot be told without a distinct reference to deified heroes and the successive dynasties of the Hellenic gods. The present work consists of tales, many of which are among the most beautiful in the mythology common to the great Aryan family of nations. The simplicity and tenderness of many of these legends suggest a comparison with the general cha racter of the Northern mythology ; while others tend in a great measure to determine the question of a patriarchal religion, of which the mythical tales of Greece are supposed to have preserved only the faint and distorted conceptions. * The tales are recounted with a ■ Mb. Cox's first set of stories were scholarly ease and grace which entitle told in such a way that every child de them to high commendation as a book for lighted to hear them, and at the same time youthful students.