Washington Metropolitan Region Transportation Demand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landover Alternative

6.0 Landover Alternative Chapter 6 describes existing conditions of the Figure 6- 1: Landover Conceptual Site Plan affected environment and identifies the environmental consequences associated with the consolidation of the FBI HQ at the Landover site. A detailed description of ¨¦§495 the methodologies employed to evaluate impacts for BRIGHTSEAT ROAD ¨¦§95 each resource and the relevant regulatory framework is given in chapter 3, Methodology. The Landover site consists of approximately 80 acres of vacant land located near the intersection of Brightseat Road and Landover Road in Prince George’s County, Maryland. It is bound on the north by Evarts Street, on the east by the Capital Beltway, on the south by Landover Road, and on the west by TRUCK & EVARTS STREET SECONDARY Brightseat Road. Previously, the site was home to the TRUCK VEHICULAR SCREENING GATE Landover Mall, which operated between 1972 and REMOTE DELIVERY 2002. As of December 2014, all facilities associated FACILITY with Landover Mall have been demolished, and only STANDBY SUBSTATION GENERATORS the surface parking lot and retaining walls remain MAIN LANDOVER ROAD VEHICULAR GATE CENTRAL UTILITY WOODMORE TOWNE CENTRE on-site. Commercial uses in proximity to the site (EXIT ONLY) PLANT MAPLE RIDGE include Woodmore Towne Centre, located across the EMPLOYEE Capital Beltway (Interstate [I]-95) to the east, and the APARTMENTS PARKING Arena Plaza Shopping Center. South of Landover VISITOR CENTER Road. West of the site along Brightseat Road is the VISITOR PARKING 202 Maple Ridge apartment complex, while H.P. Johnson Park, additional apartment and single-family residential communities are located north of the site. -

Fy20 Strategic Plan

FAIRFIELD AND SUISUN TRANSIT FY20 STRATEGIC PLAN FOUNDATION MISSION VISION At FAST, we strive to: To provide a safe and efficient transportation service for our community with . Provide sustainable and innovative service. a high standard of quality. Have a positive impact on our community and environment. Deliver convenient service so people will ride with us. PRINCIPLES STEWARDSHIP SERVICE RELATIONS POSITIVE OUTCOMES We will appropriately manage taxpayer We will provide our community with the We will work as a team to foster positive We will proactively seek innovative resources: time, money, people, and facilities highest quality service by focusing on safety, relations with each other, our customers, our improvements that result in positive and to serve the community and improve our convenience, reliability, and sustainability. community, and our stakeholders. sustainable outcomes. environment. VALUES COMMUNITY/ FACILITIES FINANCES FLEET OPERATIONS SAFETY SYSTEMS CUSTOMERS EMPLOYEES GOALS • Conduct annual FAST • Hire Transportation • Partner with City • Seek and assist with applying • Work with outside consultant • Conduct a Request for • Reduce preventable • Award contract and Customer Satisfaction Survey Manager, Transit engineering staff to continue for funding opportunities for and PG&E to develop an Proposal (RFP) for Transit accident rate to meet implement an updated to monitor performance Operations Manager, engineering, design, and fleet replacement, Fairfield- effective Fleet Ready Plan Operations Services and contract safety standards. transit data management goals and evaluate service Public Works Assistant, construction efforts on the Vacaville Train Station: Phase for the Corporation Yard. award contract. • Use DriveCam to system. quality. and Office Specialist following key projects: II construction (additional • Solicit bids/award contract • Complete a RFP identifying continually improve safety. -

Figure 2: Ballston Station Area Sites EXHIBIT NO.57A2 ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia

ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia ZONING COMMISSION Case No. 06-27 District of Columbia CASE NO.06-27 57A2 Figure 2: Ballston Station Area Sites EXHIBIT NO.57A2 ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia Case No. 06-27 Figure 3: Courthouse Station Area Sites 57A2 ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia Case No. 06-27 Figure 4: Crystal City Station Area Sites 57A2 ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia Case No. 06-27 Figure 5: Dunn-Loring-Merrifield Station Area Sites 57A2 ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia Case No. 06-27 Figure 6: Eisenhower Avenue and King Street Station Area Sites 57A2 ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia Case No. 06-27 Figure 7: Farragut West Station Area Sites 57A2 ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia Case No. 06-27 Figure 8: Friendship Heights Station Area Sites 57A2 ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia Case No. 06-27 Figure 9: Gallery Place-Chinatown Station Area Sites 57A2 ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia Case No. 06-27 57A2 Figure 10: Grosvenor-Strathmore Station Area Sites ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia Case No. 06-27 Figure 11: New Carrollton Station Area Sites 57A2 ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia Case No. 06-27 Figure 12: Silver Spring Station Area Sites 57A2 MJ Station Entrance/Exit • Office c::J Residential ZONING COMMISSION District of Columbia Case No. 06-27 Figure 13: U Street/African American Civil War Memoriai/Cardozo Station Area Sites 57A2 3. Data Collection At each site, data about the travel characteristics of individuals who work, live, shop or use the sites were collected through a series of questionnaires conducted through self-administered survey forms and oral intercept interviews. -

Quarterly Financial Report FY2017 -- Fourth Quarter April -- June 2017

Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority Fiscal Year 2017 Financials Quarterly Financial Report FY2017 ---Fourth Quarter April ---June 2017 Page 1 of 62 WASHINGTON METROPOLITAN AREA TRANSIT AUTHORITY QUARTERLY FINANCIAL REPORT FY2017 --- Q4 April --- June 2017 _________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents Section Page Key Financial Performance Indicators 3 Operating and Capital Budget Summaries 8 Operating Financials by Mode 26 Parking Facility Usage 30 Capital Expenditures 32 Jurisdictional Balances on Account 41 Grants Activity 43 Contract Activity 45 Page 2 of 62 WASHINGTON METROPOLITAN AREA TRANSIT AUTHORITY QUARTERLY FINANCIAL REPORT FY2017 --- Q4 April --- June 2017 _________________________________________________________________ Key Financial Performance Indicators Page 3 of 62 Page 4 of 62 REVENUE AND RIDERSHIP 4th Quarter FY2017 REVENUE (in Millions) FY2016 Actual FY2017 Budget FY2017 Actual $85M 81 81 $80M 80 79 79 78 78 78 78 76 $75M 75 72 72 72 72 70 70 $70M 70 69 69 68 68 67 67 67 66 66 65 65 65 65 $65M 64 63 63 60 $60M 60 59 59 $55M $50M Jul Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Cumulative Revenue Variance $0M (17.0) -$50M (27.0) (36.6) (45.6) (55.9) (64.6) (69.8) -$100M (76.9) (86.9) (103.0) (109.5) -$150M (116.3) RIDERSHIP (trips in Thousands) Q4 Q4-FY2016 Q4-FY2017 Variance FY17 Actual Actual Budget Prior Year Budget Metrorail 48,768 47,336 54,466 -3% -13% Metrobus 32,142 30,514 35,118 -5% -13% MetroAccess 595 607 618 2% -2% System Total 81,504 78,457 90,202 -4% -13% -

Issue: Shopping Malls Shopping Malls

Issue: Shopping Malls Shopping Malls By: Sharon O’Malley Pub. Date: August 29, 2016 Access Date: October 1, 2021 DOI: 10.1177/237455680217.n1 Source URL: http://businessresearcher.sagepub.com/sbr-1775-100682-2747282/20160829/shopping-malls ©2021 SAGE Publishing, Inc. All Rights Reserved. ©2021 SAGE Publishing, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Can they survive in the 21st century? Executive Summary For one analyst, the opening of a new enclosed mall is akin to watching a dinosaur traversing the landscape: It’s something not seen anymore. Dozens of malls have closed since 2011, and one study predicts at least 15 percent of the country’s largest 1,052 malls could cease operations over the next decade. Retail analysts say threats to the mall range from the rise of e-commerce to the demise of the “anchor” department store. What’s more, traditional malls do not hold the same allure for today’s teens as they did for Baby Boomers in the 1960s and ’70s. For malls to remain relevant, developers are repositioning them into must-visit destinations that feature not only shopping but also attractions such as amusement parks or trendy restaurants. Many are experimenting with open-air town centers that create the feel of an urban experience by positioning upscale retailers alongside apartments, offices, parks and restaurants. Among the questions under debate: Can the traditional shopping mall survive? Is e-commerce killing the shopping mall? Do mall closures hurt the economy? Overview Minnesota’s Mall of America, largest in the U.S., includes a theme park, wedding chapel and other nonretail attractions in an attempt to draw patrons. -

38B Map and Timetable

How to use this timetable Effective 12-18-16 ➤ Use the map to find the stops closest to where you will get on and off the bus. ➤ Select the schedule (Weekday, Saturday, Sunday) for when you will travel. Along the top of the schedule, Ballston-Farragut Square Line find the stop at or nearest the point where you will get on the bus. Follow that column down to the time you want to leave. ➤ Use the same method to find the times the bus is scheduled to arrive at the stop where you will get off the bus. Serves these locations- ➤ If the bus stop is not listed, use the Brinda servicio a estas ubicaciones time shown for the bus stop before it as the time to wait at the stop. l Ballston-MU station ➤ The end-of-the-line or last stop is listed l Clarendon station in ALL CAPS on the schedule. l Court House station Rosslyn station Cómo Usar este Horario l ➤ Use este mapa para localizar las l Georgetown paradas más cercanas a donde se l Farragut North station subirá y bajará del autobús. l Farragut West station ➤ Seleccione el horario (Entre semana, sábado, domingo) de cuando viajará. A lo largo de la parte superior del horario, localice la parada o el punto más cercano a la parada en la que se subirá al autobús. Siga esa columna hacia abajo hasta la hora en la que desee salir. ➤ Utilice el mismo método para localizar las horas en que el autobús está programado para llegar a la parada en donde desea bajarse del autobús. -

Resolution #20-9

BALTIMORE METROPOLITAN PLANNING ORGANIZATION BALTIMORE REGIONAL TRANSPORTATION BOARD RESOLUTION #20-9 RESOLUTION TO ENDORSE THE UPDATED BALTIMORE REGION COORDINATED PUBLIC TRANSIT – HUMAN SERVICES TRANSPORTATION PLAN WHEREAS, the Baltimore Regional Transportation Board (BRTB) is the designated Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) for the Baltimore region, encompassing the Baltimore Urbanized Area, and includes official representatives of the cities of Annapolis and Baltimore; the counties of Anne Arundel, Baltimore, Carroll, Harford, Howard, and Queen Anne’s; and representatives of the Maryland Departments of Transportation, the Environment, Planning, the Maryland Transit Administration, Harford Transit; and WHEREAS, the Baltimore Regional Transportation Board as the Metropolitan Planning Organization for the Baltimore region, has responsibility under the provisions of the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act for developing and carrying out a continuing, cooperative, and comprehensive transportation planning process for the metropolitan area; and WHEREAS, the Federal Transit Administration, a modal division of the U.S. Department of Transportation, requires under FAST Act the establishment of a locally developed, coordinated public transit-human services transportation plan. Previously, under MAP-21, legislation combined the New Freedom Program and the Elderly Individuals and Individuals with Disabilities Program into a new Enhanced Mobility of Seniors and Individuals with Disabilities Program, better known as Section 5310. Guidance on the new program was provided in Federal Transit Administration Circular 9070.1G released on June 6, 2014; and WHEREAS, the Federal Transit Administration requires a plan to be developed and periodically updated by a process that includes representatives of public, private, and nonprofit transportation and human services providers and participation by the public. -

News and Notes Prince George's County J § 'W

News and Notes Prince George's County J § 'W . CO , Historical Society ! = = 3 e 'MaritlU' February 1997 Our 45th Year Volume XXV Number 1 BOARD OF DIRECTORS 1997 President - Jane Eagen Directors 1997-1999 Past Presidents Vice President - Eugene Roberts, Jr. Mildred Ridgeley Gray John Giannetti Secretary - Sarah Bourne Melinda Alter Paul T. Lanham Treasurer - John Bourne Katherine Clagett Warren Rhoads Historian - Frederick DeMarr Directors 1996-1998 W.C. (Bud) Button Editor - Sharon Howe Sweeting Julie Bright Joyce MacDonald John Mitchell William Uber Illustration by Fred H. Greenberg from Washington Itself by E. J. Applewhite, 1986 JOIN US on SATURDAY, MARCH 8 at 2:00 pm at the Glenn Dale Community Center Mr David J. Danelski, Supreme Court Historian, will speak on Sons of Maryland on the United States Supreme Court: Thomas Johnson, Samuel Chase, Gabriel Duvall, Roger Brooke Taney and Thurgood Marshall. Mr. Danelski has researched, taught and written extensively about the United States Supreme Count. He will share little know stories and attempt to undo some popular misconceptions about these men. We have invited the members of the Duvall Society to join us for this celebration of Gabriel Duvall. The reception following the program will be at Marietta, home of Gabriel Duvall. FROM THE EDITOR'S DESK Happy New Year. You will notice on the cover the new/old Board of Directors of the Historical Society and an announcement of the meeting on Saturday, March 8 (2:00 pm, Glenn Dale Community Center) on "Sons of Maryland on the United States Supreme Court." This issue begins with the continuation of a column called Meet the Meet the Board Board written by Secretary Sarah Bourne. -

Oore Ventura County Transportation Commission

javascript:void(0) Final Audit Report June 2017 Ventura County Transportation Commission TDA Triennial Performance Audit City of Ojai oore City of Ojai Triennial Performance Audit, FY 2014-2016 Final Report Table of Contents Chapter 1: Executive Summary ........................................................ 01 Chapter 2: Review Scope and Methodology ..................................... 05 Chapter 3: Program Compliance ...................................................... 09 Chapter 4: Performance Analysis ..................................................... 15 Chapter 5: Functional Review .......................................................... 23 Chapter 6: Findings and Recommendations ..................................... 29 Moore & Associates, Inc. | 2017 City of Ojai Triennial Performance Audit, FY 2014-2016 Final Report This page intentionally blank. Moore & Associates, Inc. | 2017 City of Ojai Triennial Performance Audit, FY 2014-2016 Final Report Chapter 1 Executive Summary In 2017, the Ventura County Transportation Commission (VCTC) selected the consulting team of Moore & Associates, Inc./Ma and Associates to prepare Triennial Performance Audits of itself as the RTPA, and the nine transit operators to which it allocates funding. As one of the six statutorily designated County Transportation Commissions in the SCAG region, VCTC also functions as the respective county RTPA. The California Public Utilities Code requires all recipients of Transit Development Act (TDA) Article 4 funding to complete an independent audit on a three-year cycle in order to maintain funding eligibility. This is the first Triennial Performance Audit of the City of Ojai. The Triennial Performance Audit (TPA) of the City of Ojai’s public transit program covers the three-year period ending June 30, 2016. The Triennial Performance Audit is designed to be an independent and objective evaluation of the City of Ojai as a public transit operator, providing operator management with information on the economy, efficiency, and effectiveness of its programs across the prior three years. -

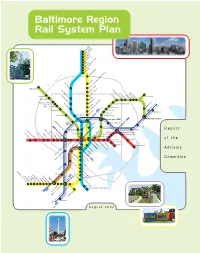

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report of the Advisory Committee August 2002 Advisory Committee Imagine the possibilities. In September 2001, Maryland Department of Transportation Secretary John D. Porcari appointed 23 a system of fast, convenient and elected, civic, business, transit and community leaders from throughout the Baltimore region to reliable rail lines running throughout serve on The Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Advisory Committee. He asked them to recommend the region, connecting all of life's a Regional Rail System long-term plan and to identify priority projects to begin the Plan's implemen- important activities. tation. This report summarizes the Advisory Committee's work. Imagine being able to go just about everywhere you really need to go…on the train. 21 colleges, 18 hospitals, Co-Chairs 16 museums, 13 malls, 8 theatres, 8 parks, 2 stadiums, and one fabulous Inner Harbor. You name it, you can get there. Fast. Just imagine the possibilities of Red, Mr. John A. Agro, Jr. Ms. Anne S. Perkins Green, Blue, Yellow, Purple, and Orange – six lines, 109 Senior Vice President Former Member We can get there. Together. miles, 122 stations. One great transit system. EarthTech, Inc. Maryland House of Delegates Building a system of rail lines for the Baltimore region will be a challenge; no doubt about it. But look at Members Atlanta, Boston, and just down the parkway in Washington, D.C. They did it. So can we. Mr. Mark Behm The Honorable Mr. Joseph H. Necker, Jr., P.E. Vice President for Finance & Dean L. Johnson Vice President and Director of It won't happen overnight. -

Accessible Transportation Options for People with Disabilities and Senior Citizens

Accessible Transportation Options for People with Disabilities and Senior Citizens In the Washington, D.C. Metropolitan Area JANUARY 2017 Transfer Station Station Features Red Line • Glenmont / Shady Grove Bus to Airport System Orange Line • New Carrollton / Vienna Parking Station Legend Blue Line • Franconia-Springfield / Largo Town Center in Service Map Hospital Under Construction Green Line • Branch Ave / Greenbelt Airport Full-Time Service wmata.com Yellow Line • Huntington / Fort Totten Customer Information Service: 202-637-7000 Connecting Rail Systems Rush-Only Service: Monday-Friday Silver Line • Wiehle-Reston East / Largo Town Center TTY Phone: 202-962-2033 6:30am - 9:00am 3:30pm - 6:00pm Metro Transit Police: 202-962-2121 Glenmont Wheaton Montgomery Co Prince George’s Co Shady Grove Forest Glen Rockville Silver Spring Twinbrook B30 to Greenbelt BWI White Flint Montgomery Co District of Columbia College Park-U of Md Grosvenor - Strathmore Georgia Ave-Petworth Takoma Prince George’s Plaza Medical Center West Hyattsville Bethesda Fort Totten Friendship Heights Tenleytown-AU Prince George’s Co Van Ness-UDC District of Columbia Cleveland Park Columbia Heights Woodley Park Zoo/Adams Morgan U St Brookland-CUA African-Amer Civil Dupont Circle War Mem’l/Cardozo Farragut North Shaw-Howard U Rhode Island Ave Brentwood Wiehle-Reston East Spring Hill McPherson Mt Vernon Sq NoMa-Gallaudet U New Carrollton Sq 7th St-Convention Center Greensboro Fairfax Co Landover Arlington Co Tysons Corner Gallery Place Union Station Chinatown Cheverly 5A to -

Howard County Transportation

Howard County Transportation September MTB Meeting September 29, 2020 Today’s Agenda 1) Approval of Agenda for Meeting – Chairperson Schoen 2) Approval of AUGUST 25, 2020 Meeting Minutes – Chairperson Schoen 3) Public Comment – General Topics (Participants that have signed up in advance will have 3 minutes each to address the MTB) 4) Follow up on Roadway Safety Plan Comments (verbal) – David Cookson & Cindy Burch Chris Eatough 5) Approval No presentation will be provided. For review of Complete of materials please see: Streets https://www.howardcountymd.gov/Depart Engagement ments/County- Plan – Administration/Transportation/Complete- Streets/Community-Engagement Bruce Gartner MDOT CTP Statewide book – includes overview 6) MDOT CTP and capital program for all business units with the Overview and exception of MDOT-SHA County capital programs. MTA Service Link for document: Reductions http://www.mdot.maryland.gov/newMDOT/Plann ing/CTP/CTP_21_26/Draft_Documents/Entire%20 FY%2021-26%20CTP.pdf Long Term State Funding Decisions Negatively Impact Baltimore Region • Significant Transit Reductions in Baltimore Region versus limited impact to Central MD Transit Plan Washington Suburbs creates a concern about regional equity. • How will the Purple Line legal and contracting problems impact Baltimore Region? • What Can MDOT and Governor Hogan do to reallocate existing state or future federal funds to scale back some of the transit reductions being proposed in this CTP? MDOT Consolidated Transportation Program Reductions MDOT’s draft 6-year Consolidated Transportation Program (CTP) for FY2021-2026. shows a $2.9 billion reduction over the last 6-year plan • While the cuts are distributed across MDOT modes, Maryland’s contribution to WMATA is 100% funded for capital and operating (as of 9-25-20) • $150 million in cuts to MTA on top of last year’s $303 million reduction to the 6-year CTP will further impact the failing transit network in the Baltimore region • Cuts to system preservation budgets for all MDOT modes has a longer term fiscal impact on our transportation network.