Measurements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intro to Measurement Uncertainty 2011

Measurement Uncertainty and Significant Figures There is no such thing as a perfect measurement. Even doing something as simple as measuring the length of a pencil with a ruler is subject to limitations that can affect how close your measurement is to its true value. For example, you need to consider the clarity and accuracy of the scale on the ruler. What is the smallest subdivision of the ruler scale? How thick are the black lines that indicate centimeters and millimeters? Such ideas are important in understanding the limitations of use of a ruler, just as with any measuring device. The degree to which a measured quantity compares to the true value of the measurement describes the accuracy of the measurement. Most measuring instruments you will use in physics lab are quite accurate when used properly. However, even when an instrument is used properly, it is quite normal for different people to get slightly different values when measuring the same quantity. When using a ruler, perception of when an object is best lined up against the ruler scale may vary from person to person. Sometimes a measurement must be taken under less than ideal conditions, such as at an awkward angle or against a rough surface. As a result, if the measurement is repeated by different people (or even by the same person) the measured value can vary slightly. The degree to which repeated measurements of the same quantity differ describes the precision of the measurement. Because of limitations both in the accuracy and precision of measurements, you can never expect to be able to make an exact measurement. -

1201 Lab Manual Table of Contents

1201 LAB MANUAL TABLE OF CONTENTS WARNING: The Pasco carts & track components have strong magnets inside of them. Strong magnetic fields can affect pacemakers, ICDs and other implanted medical devices. Many of these devices are made with a feature that deactivates it with a magnetic field. Therefore, care must be taken to keep medical devices minimally 1’ away from any strong magnetic field. Introduction 3 Laboratory Skills Laboratory I: Physics Laboratory Skills 7 Problem #1: Constant Velocity Motion 1 9 Problem #2: Constant Velocity Motion 2 15 Problem #3: Measurement and Uncertainty 21 Laboratory I Cover Sheet 31 General Laws of Motion Laboratory II: Motion and Force 33 Problem #1: Falling 35 Problem #2: Motion Down an Incline 39 Problem #3: Motion Up and Down an Incline 43 Problem #4: Normal Force and Frictional Force 47 Problem #5: Velocity and Force 51 Problem #6: Two-Dimensional Motion 55 Table of Coefficients of Friction 59 Check Your Understanding 61 Laboratory II Cover Sheet 63 Laboratory III: Statics 65 Problem #1: Springs and Equilibrium I 67 Problem #2: Springs and Equilibrium II 71 Problem #3: Leg Elevator 75 Problem #4: Equilibrium of a Walkway 79 Problem #5: Designing a Mobile 83 Problem #6: Mechanical Arm 87 Check Your Understanding 91 Laboratory III Cover Sheet 93 Laboratory IV: Circular Motion and Rotation 95 Problem #1: Circular Motion 97 Problem #2: Rotation and Linear Motion at Constant Speed 101 Problem #3: Angular and Linear Acceleration 105 Problem #4: Moment of Inertia of a Complex System 109 Problem #5: Moments -

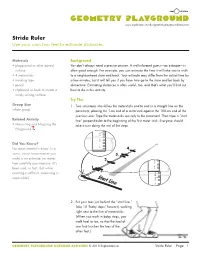

Stride Ruler Use Your Own Two Feet to Estimate Distances

www.exploratorium.edu/geometryplayground/activities Stride Ruler Use your own two feet to estimate distances. Materials Background • playground or other paved You don’t always need a precise answer. A well-informed guess—an estimate—is surface often good enough. For example, you can estimate the time it will take you to walk • 4 metersticks to a neighborhood store and back. Your estimate may differ from the actual time by • masking tape a few minutes, but it will tell you if you have time go to the store and be back by • pencil dinnertime. Estimating distances is often useful, too, and that’s what you’ll find out • clipboard or book to create a how to do in this activity. sturdy writing surface Try This Group Size 1. Two volunteers should lay the metersticks end to end in a straight line on the whole group pavement, placing the 1-cm end of a meterstick against the 100-cm end of the previous one. Tape the metersticks securely to the pavement. Then tape a “start Related Activity line” perpendicular to the beginning of the first meter stick. Everyone should • Measuring and Mapping the take a turn doing the rest of the steps. Playground Did You Know? No measurement is exact. In a 4. sense, every measurement you 3. make is an estimate, no matter 2. how carefully you measure. (It’s been said, in fact, that while 1. counting is difficult, measuring is impossible!) St art Line 2. Put your toes just behind the “start line.” Take 10 “baby steps” forward, walking right next to the line of metersticks. -

Answer Key • Lesson 1: M, Dm, Cm, Mm

Answer Key • Lesson 1: m, dm, cm, mm Student Guide Questions 1–23 (SG pp. 448–452) m, dm, cm, mm Meters (m) 1. Yes Your teacher made marks 1 and 2 meters above the floor. Use these marks to help you 2. No answer the questions below. 1. Are you more than 1 meter tall? 3. Answers will vary. 2. Are you more than 2 meters tall? 3. Are you closer to 1 meter or 2 meters? 4.* A sample class data table follows (Figure 1 4. Measure objects around the classroom to the nearest whole meter. The symbol for from lesson). meter is m. Keep track of the data on the Class Measurement Tables in the Student To the Nearest Meter Activity Book. To the Nearest Meter Measurement Measurement Object Object (nearest m) (nearest m) Height of door Copyright © Kendall Hunt Publishing Company Height of door 2 m Width of classroom Length of Width of classroom 8 m classroom Width of chalkboard Length of classroom 14 m Length of paper clip Width of chalkboard 5 m Length of pencil Length of paper clip 0 m Length of pencil 0 m 5. A measurement of 0 m tells you the object is less than 0.5 m long. Centimeters or 448 SG • Grade 4 • Unit 10 • Lesson 1 m, dm, cm, mm decimeters are more appropriate units. 6. Two possible answers: a pencil and the Student Guide - Page 448 diameter of a nickel. 7. Two possible answers: The length of a room and the height of a building. 5. -

Measurements Purpose Equipment Discussion

rev 05/2019 Measurements Purpose To learn the proper use of a meterstick, vernier caliper, micrometer, and electronic scale, and to learn how to use the correct number of significant figures in data and results. Equipment Meterstick, 2-meterstick, vernier caliper, micrometer, laboratory balance, ruler, metal cylinder. Discussion The number of significant figures in a measurement depends on the measuring device and its precision. When an object is measured in a same manner, a vernier caliper has a greater precision than a meterstick and a micrometer has a greater precision than a vernier caliper. A measurement reading should have one more significant figure than the smallest subdivision marked on the scale. 2 (Main scale) 3 0 (Vernier scale) Alignment at 7 2.1 cm + 0.070 cm = 2.170 cm (main scale at vernier 0 mark) (vernier scale) Vernier Caliper. Example of reading: The main scale gives a reading to 1/10 of cm at the 0 mark on the vernier scale. The next digit (the second decimal place in cm) is made on the vernier scale where the marks line up. If a mark on the vernier scale is aligned with a mark on the main scale as in the first example, the mark on the vernier scale gives the next digit and the estimated figure is 0. 1 2 (Main scale) 3 0 (Vernier scale) No alignment. Phase change for 2 and 3 marks. 2.0 cm + 0.025 cm = 2.025 cm (main scale at vernier 0 mark) (vernier scale) Example 2: If no marks are aligned, there is a phase change between marks. -

Central Supply Catalog

Central Supply Catalog 2010-2011 Kalispell Public Schools Auxiliary Services Building 514 E. Washington Street Kalispell, MT 59901 Contacts: Bruce Nikunen [email protected] (406) 758-8391 Sandy Weeks [email protected] (406) 758-8392 TABLE OF CONTENTS Contacts . Front Cover Introduction . 1 Medical Supplies . 2 Office Supplies . 3-14 Order Log . Back Cover Page 1 INTRODUCTION Please discard any old Central Supply catalogs you may have and use this catalog. Make sure requisitions have proper budget codes, stock numbers, item description, and are signed by the Department Head or Building Principal. A pack slip will be included with the items ordered that will show you the current costs of the order. We invite you to visit Central Supply so that you have a better understanding of the items that are stocked and so that you can get to know what items you may need. Some items are limited and will only be issued until the stock is depleted. To better help you in ordering large quantities, we have listed some items and how they are sent to us. However, you can still order individually if you choose. Cards, Index 3” x 5”/4” x 6” = 10 pkg/box Cards, Index, 5” x 8” = 5 pkg/box Chalks = 12 sticks/box = 12 boxes/carton Covers, Duotang, pocket folder w/clip = 100/carton Envelopes, Manila clasp all sizes = 100/box Erasers/Pencil top = 144/box File Folder, legal & letter = 5 boxes/case Glue Stick = 12 tubes/pkg Markers, Hi-lighters = 12/box Markers, Sharpie = 12/box Markers, Mr. -

Measurement.Pdf (331 Kb) Copyright and License Information Can Be Found Here

Lab 1 Meaningful Measurements Experimental Objectives Determine the material of the objects by calculating their density and matching it to the accepted values for various common materials. Introduction Physics is a science which is based on precise measurements of the seven fundamental physical quantities, three of which are: time (in seconds), length (in meters) and mass (in kilograms); and all of these measurements have an experimental uncertainty associated with them. It is very important for the experimenter to estimate these experimental uncertainties for every measurement taken. There are three factors that must be taken into account when estimating the uncertainty of a measurement: 1. statistical variations in the measurements, 2. using one-half of the smallest division on the measurement instrument, 3. any mechanical motions of the apparatus. Physicists study the physical relationships between these dened fundamental quantities and usually give a name to the newly derived physical quantity. These derived physical quantities have units which are combi- nations of the units of the fundamental ones. For example, the product of the lengths (in meters, m) of the three sides of a cube is called volume and has units of m3. The ratio of mass to volume is called density and kg has units of 3 . The concepts of volume and density are therefore derived from the fundamental physical quantities, ratherm than fundamental themselves. 1.1 Student Outcomes Knowledge Developed: In this exercise, students should learn how to make precise and accurate length mea- surements with a meter stick and two types of calipers, how to read a vernier scale, and how to estimate uncertainty in a measurement. -

Appendices, Glossary, Index, and Photo Credits

Appendices Appendix A Supplemental Practice Problems . .871 Appendix B Math Handbook . .887 Arithmetic Operations . .887 Math Scientific Notation . .889 Handbook Operations with Scientific Notation . .891 Square and Cube Roots . .892 Significant Figures . .893 Solving Algebraic Equations . .897 Dimensional Analysis . .900 Unit Conversion . .901 Drawing Line Graphs . .903 Using Line Graphs . .904 Ratios, Fractions, and Percents . .907 Operations Involving Fractions . .909 Logarithms and Antilogarithms . .910 Appendix C Tables . .912 C-1 Color Key . .912 C-2 Symbols and Abbreviations . .912 C-3 SI Prefixes . .913 C-4 The Greek Alphabet . .913 C-5 Physical Constants . .913 C-6 Properties of Elements . .914 C-7 Electron Configurations of Elements . .917 C-8 Names and Charges of Polyatomic Ions . .919 C-9 Ionization Constants . .919 C-10 Solubility Guidelines . .920 C-11 Specific Heat Values . .921 C-12 Molal Freezing Point Depression and Boiling Point Elevation Constants . .921 C-13 Heat of Formation Values . .921 Appendix D Solutions to Practice Problems . .922 Appendix E Try at Home Labs . .952 Glossary/Glosario . .965 Index . .989 870 Chemistry: Matter and Change APPENDIXCHAPTER A## PracticeASSESSMENT Problems Practice! Chapter 2 Section 2-1 1. The density of a substance is 4.8 g/mL. What is the volume of a sample that is 19.2 g? 2. A 2.00-mL sample of substance A has a density of 18.4 g/mL and a 5.00-mL sample of substance B has a density of 35.5 g/mL. Do you have an equal mass of substances A and B? Section 2-2 3. Express the following quantities in scientific notation. -

Mass, Volum EXPERIMENT 1 Mass, Volume and Density

EXPERIMENT 1 Mass, Volume and Density PURPOSE 1. Familiarize with basic measurement tools such as the vernier caliper, micrometer, and weighing balance. 2. Learn how to use the concepts of the significant figures, the experimental uncertainty (error) and some methods of error and data analysis in your experimental measurements. EQUIPMENT A steel ball, a rectangular aluminum block, a brass cylinder, a alumi num annular cylinder, vernier calipers, micrometer, balance. THEORY • Least Count of an Instrument Scale The Least Count of an instrument is the smallest subdivision marked on its scale. This is the unit of the smallest reading that can be made without estimating. Figure 1 Least count Meterstick is commonly calibrated in centimeter (numbered major division) with a least count, or Smallest marked subdivision, of millimeter. • Vernier Caliper Figure 2 Vernier Caliper The vernier caliper in Fig.2 consists of a rule with a main engraved scale and a movable jaw with an engraved vernier scale. The span of the lower jaw is used to measure length and is particularly convenient for measuring the diameter of a cylindrical object. The span of the upper jaw is used to measure distances between two surfaces (e.g. the inside diameter of a hollow cylindrical object). 10 The main scale is calibrated in centimeters with a millimeter least count, and the movable vernier scale has 10 divisions that cover 9 divisions on the main scale. Figure 3 shows an example of reading the vernier scale on a caliper. Main scale Vernier zero mark 1 cm + 0.2 cm + 0.03 cm + 0.000 cm = 1.230 cm (major division) (minor division) (aligned mark) (estimated of doubt) (a) Main scale Vernier zero mark 1 cm + 0.2 cm + 0.025 cm = 1.225 cm (major division) (minor division) (phase change for 2 and 3 marks) (b) Figure 3 Vernier scale . -

An Introduction to Computational Physics, Second Edition.Pdf

An Introduction to Computational Physics Numerical simulation is now an integrated part of science and technology. Now in its second edition, this comprehensive textbook provides an introduction to the basic methods of computational physics, as well as an overview of recent progress in several areas of scientific computing. The author presents many step-by-step examples, including program listings in JavaTM, of practical numerical methods from modern physics and areas in which computational physics has made significant progress in the last decade. The first half of the book deals with basic computational tools and routines, covering approximation and optimization of a function, differential equations, spectral analysis, and matrix operations. Important concepts are illustrated by relevant examples at each stage. The author also discusses more advanced topics, such as molecular dynamics, modeling continuous systems, Monte Carlo methods, the genetic algorithm and programming, and numerical renormalization. This new edition has been thoroughly revised and includes many more examples and exercises. It can be used as a textbook for either undergraduate or first-year graduate courses on computational physics or scientific computation. It will also be a useful reference for anyone involved in computational research. Tao Pang is Professor of Physics at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. Following his higher education at Fudan University, one of the most prestigious institutions in China, he obtained his Ph.D. in condensed matter theory from the University of Minnesota in 1989. He then spent two years as a Miller Research Fellow at the University of California, Berkeley, before joining the physics faculty at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas in the fall of 1991. -

2019 Course Resource List Table of Contents

2019 Course Resource List Table of Contents Kindergarten English Language Arts ................................................................................................................... 4 Math in Focus ................................................................................................................................. 5 Science ........................................................................................................................................... 6 Social Studies ................................................................................................................................. 7 1st Grade English Language Arts ................................................................................................................... 8 Math in Focus ................................................................................................................................. 9 Science ......................................................................................................................................... 10 Social Studies ............................................................................................................................... 11 2nd Grade English Language Arts ................................................................................................................. 12 Math in Focus ............................................................................................................................... 13 Science ........................................................................................................................................ -

Area and Perimeter

Name: Date: r te p a h C Area and Perimeter Practice 1 Area Draw and color two different figures. Use 4 squares ( ) and 2 half-squares ( ) for each figure. 1. © Marshall Cavendish International (Singapore) Private Limited. Private (Singapore) International © Marshall Cavendish 211 Lesson 19.1 Area The figures are made of square and half-square tiles. Write the area of each figure in the table. A B C D E F 2. Figure Area Each square ( ) is 1 square unit. Each A square units half-square ( ) is 1 square unit. Limited. Private (Singapore) International © Marshall Cavendish B square units 2 C square units D square units E square units F square units 3. Figure and Figure have the same area. 4. Figure has the largest area. 212 Chapter 19 Area and Perimeter Name: Date: Draw two different fi gures with the same area on the grid. 5. 1 unit 1 unit Add squares ( ) or half-squares ( ) to each fi gure to make its area 7 square units. 6. © Marshall Cavendish International (Singapore) Private Limited. Private (Singapore) International © Marshall Cavendish 213 Lesson 19.1 Area Complete. Cut out the triangle tiles. Use all the tiles to make three figures with different areas. Glue them in the spaces below. 7. ABC 8. Which figure has the smallest area? Figure 9. Which figure has the largest area? Figure 10. Order the figures from smallest to largest area. Limited. Private (Singapore) International © Marshall Cavendish , , smallest 214 Chapter 19 Area and Perimeter Name: Date: Practice 2 Square Units (cm2 and in.2) Find the area of each shaded figure in square centimeters (cm2).