Confronting the Political Power of Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Political Culture of Canada

CHAPTER 2 The Political Culture of Canada LEARNING OBJECTIVES By the end of this chapter you should be able to • Define the terms political culture, ideology, and cleavages. • Describe the main principles of each of the major ideologies in Canada. • Describe the ideological orientation of the main political parties in Canada. • Describe the major cleavages in Canadian politics. Introduction Canadian politics, like politics in other societies, is a public conflict over different conceptions of the good life. Canadians agree on some important matters (e.g., Canadians are overwhelmingly committed to the rule of law, democracy, equality, individual rights, and respect for minorities) and disagree on others. That Canadians share certain values represents a substantial consensus about how the political system should work. While Canadians generally agree on the rules of the game, they dis- agree—sometimes very strongly—on what laws and policies the government should adopt. Should governments spend more or less? Should taxes be lower or higher? Should governments build more prisons or more hospitals? Should we build more pipelines or fight climate change? Fortunately for students of politics, different conceptions of the good life are not random. The different views on what laws and policies are appropriate to realize the ideologies Specific bundles of good life coalesce into a few distinct groupings of ideas known as ideologies. These ideas about politics and the good ideologies have names that are familiar to you, such as liberalism, conservatism, and life, such as liberalism, conserva- (democratic) socialism, which are the principal ideologies in Canadian politics. More tism, and socialism. Ideologies radical ideologies, such as Marxism, communism, and fascism, are at best only mar- help people explain political ginally present in Canada. -

Information Warfare, International Law, and the Changing Battlefield

ARTICLE INFORMATION WARFARE, INTERNATIONAL LAW, AND THE CHANGING BATTLEFIELD Dr. Waseem Ahmad Qureshi* ABSTRACT The advancement of technology in the contemporary era has facilitated the emergence of information warfare, which includes the deployment of information as a weapon against an adversary. This is done using a numBer of tactics such as the use of media and social media to spread propaganda and disinformation against an adversary as well as the adoption of software hacking techniques to spread viruses and malware into the strategically important computer systems of an adversary either to steal confidential data or to damage the adversary’s security system. Due to the intangible nature of the damage caused By the information warfare operations, it Becomes challenging for international law to regulate the information warfare operations. The unregulated nature of information operations allows information warfare to Be used effectively By states and nonstate actors to gain advantage over their adversaries. Information warfare also enhances the lethality of hyBrid warfare. Therefore, it is the need of the hour to arrange a new convention or devise a new set of rules to regulate the sphere of information warfare to avert the potential damage that it can cause to international peace and security. ABSTRACT ................................................................................................. 901 I. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................... 903 II. WHAT IS INFORMATION WARFARE? ............................. -

In the Court of Chancery of the State of Delaware Karen Sbriglio, Firemen’S ) Retirement System of St

EFiled: Aug 06 2021 03:34PM EDT Transaction ID 66784692 Case No. 2018-0307-JRS IN THE COURT OF CHANCERY OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE KAREN SBRIGLIO, FIREMEN’S ) RETIREMENT SYSTEM OF ST. ) LOUIS, CALIFORNIA STATE ) TEACHERS’ RETIREMENT SYSTEM, ) CONSTRUCTION AND GENERAL ) BUILDING LABORERS’ LOCAL NO. ) 79 GENERAL FUND, CITY OF ) BIRMINGHAM RETIREMENT AND ) RELIEF SYSTEM, and LIDIA LEVY, derivatively on behalf of Nominal ) C.A. No. 2018-0307-JRS Defendant FACEBOOK, INC., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) PUBLIC INSPECTION VERSION ) FILED AUGUST 6, 2021 v. ) ) MARK ZUCKERBERG, SHERYL SANDBERG, PEGGY ALFORD, ) ) MARC ANDREESSEN, KENNETH CHENAULT, PETER THIEL, JEFFREY ) ZIENTS, ERSKINE BOWLES, SUSAN ) DESMOND-HELLMANN, REED ) HASTINGS, JAN KOUM, ) KONSTANTINOS PAPAMILTIADIS, ) DAVID FISCHER, MICHAEL ) SCHROEPFER, and DAVID WEHNER ) ) Defendants, ) -and- ) ) FACEBOOK, INC., ) ) Nominal Defendant. ) SECOND AMENDED VERIFIED STOCKHOLDER DERIVATIVE COMPLAINT TABLE OF CONTENTS Page(s) I. SUMMARY OF THE ACTION...................................................................... 5 II. JURISDICTION AND VENUE ....................................................................19 III. PARTIES .......................................................................................................20 A. Plaintiffs ..............................................................................................20 B. Director Defendants ............................................................................26 C. Officer Defendants ..............................................................................28 -

ASD-Covert-Foreign-Money.Pdf

overt C Foreign Covert Money Financial loopholes exploited by AUGUST 2020 authoritarians to fund political interference in democracies AUTHORS: Josh Rudolph and Thomas Morley © 2020 The Alliance for Securing Democracy Please direct inquiries to The Alliance for Securing Democracy at The German Marshall Fund of the United States 1700 18th Street, NW Washington, DC 20009 T 1 202 683 2650 E [email protected] This publication can be downloaded for free at https://securingdemocracy.gmfus.org/covert-foreign-money/. The views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the views of the authors alone. Cover and map design: Kenny Nguyen Formatting design: Rachael Worthington Alliance for Securing Democracy The Alliance for Securing Democracy (ASD), a bipartisan initiative housed at the German Marshall Fund of the United States, develops comprehensive strategies to deter, defend against, and raise the costs on authoritarian efforts to undermine and interfere in democratic institutions. ASD brings together experts on disinformation, malign finance, emerging technologies, elections integrity, economic coercion, and cybersecurity, as well as regional experts, to collaborate across traditional stovepipes and develop cross-cutting frame- works. Authors Josh Rudolph Fellow for Malign Finance Thomas Morley Research Assistant Contents Executive Summary �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 1 Introduction and Methodology �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

The Great Hack - Netflix Documentary Review

The Great Hack - Netflix documentary review The Great Hack is a documentary discussing the ideas of how data and user actions on devices can create individual profiles of you and how companies can use these profiles and personality traits based on a user actions to target you on advertisements that are specifically for that type of character and drive persuasion. This is much more effective than randomly sending adverts to random users. The documentary focuses on a company that does this called Cambridge Analytica which is the worlds leading data driven communications company and David Carrol an associate professor who wokred on exposing this companies unethical and illegal ways of gaining access to users data and using it to drive votes for specific campaigns. Cambridge Analytica played a big part in the 2016 Presidential campaign. They spent 6 months sending surveys to users which were designed to create and find personailty profiles which were then sent back and would be targeted videos and other propaganda through media. This could be a video that would pop up on a persons recomended page on youtube which could be spreading shame to Hilary Clinton in this case and therefore drive the user to vote for Trump. Further on during the documentary, you are introduced to Carole Cadwalladr who was the investigative jounarlist for the Guardian. She investigated Cambridge Analytica and how it tied to the Brexit campaign. Other students should watch this as it gives you an incite on how big and important data can be and be used and manipulated and it one of the big reasons why actions like Brexit and Trump becoming president are in place today. -

The Cambridge Analytica Files

For more than a year we’ve been investigating Cambridge Analytica and its links to the Brexit Leave campaign in the UK and Team Trump in the US presidential election. Now, 28-year-old Christopher Wylie goes on the record to discuss his role in hijacking the profiles of millions of Facebook users in order to target the US electorate by Carole Cadwalladr Sun 18 Mar 2018 06:44 EDT The first time I met Christopher Wylie, he didn’t yet have pink hair. That comes later. As does his mission to rewind time. To put the genie back in the bottle. By the time I met him in person [www.theguardian.com/uk- news/video/2018/mar/17/cambridge-analytica- whistleblower-we-spent-1m-harvesting-millions-of- facebook-profiles-video], I’d already been talking to him on a daily basis for hours at a time. On the phone, he was clever, funny, bitchy, profound, intellectually ravenous, compelling. A master storyteller. A politicker. A data science nerd. Two months later, when he arrived in London from Canada, he was all those things in the flesh. And yet the flesh was impossibly young. He was 27 then (he’s 28 now), a fact that has always seemed glaringly at odds with what he has done. He may have played a pivotal role in the momentous political upheavals of 2016. At the very least, he played a From www.theguardian.com/news/2018/mar/17/data-war-whistleblower-christopher-wylie-faceook-nix-bannon- trump 1 20 March 2018 consequential role. At 24, he came up with an idea that led to the foundation of a company called Cambridge Analytica, a data analytics firm that went on to claim a major role in the Leave campaign for Britain’s EU membership referendum, and later became a key figure in digital operations during Donald Trump’s election [www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/nov/09/how- did-donald-trump-win-analysis] campaign. -

Neoliberalism As Historical Narrative: Some Reflections, by Josh Cole

JOSH COLE Neoliberalism as Historical Narrative: Some Reflections n a potentially seismic contribution to the study of knowledge and Ipower (cut short by his death in 1962) the sociologist C. Wright Mills argued that the “first rule for understanding the human condition”, is that people “live in second-hand worlds”. They are aware of much more than they have personally experienced; and their own experience is al- ways indirect. “The quality of their lives is determined by meanings they have received from others.”1 This phenomenon — in which modern “consciousness and existence” is mediated by symbols which “focus ex- perience [and] organize knowledge” is central to the understanding of nationalism and history, not least in Canada.2 Through communications — embodied in media, school curricula, in statues, museums and monu- ments — we learn to love our country and the history that seems to ‘nat- urally’ inform it. So much so that, as Benedict Anderson argues, we are willing to lay down our lives (or those of our fellow citizens) in its name.3 Yet, the paradox is that nations and their national histories are not eternal, but are themselves historical artifacts of a strikingly recent invention. There is less ‘blood and soil’ than we might imagine, and more technology at work in it. What we today recognize as nationalism is a modern phenomenon, involving a break with a past in which social life was organized hierarchically under “sovereigns whose right to rule was divinely prescribed and sanctioned.” OUR SCHOOLS/OUR SELVES “Cosmological time” — that is, time conditioned by the natural rhythms of life — was dealt a severe blow by the development of sciences like geology and astronomy on the one hand, and new technologies such as chronometers, clocks, and compasses on the other. -

Cairncross Review a Sustainable Future for Journalism

THE CAIRNCROSS REVIEW A SUSTAINABLE FUTURE FOR JOURNALISM 12 TH FEBRUARY 2019 Contents Executive Summary 5 Chapter 1 – Why should we care about the future of journalism? 14 Introduction 14 1.1 What kinds of journalism matter most? 16 1.2 The wider landscape of news provision 17 1.3 Investigative journalism 18 1.4 Reporting on democracy 21 Chapter 2 – The changing market for news 24 Introduction 24 2.1 Readers have moved online, and print has declined 25 2.2 Online news distribution has changed the ways people consume news 27 2.3 What could be done? 34 Chapter 3 – News publishers’ response to the shift online and falling revenues 39 Introduction 39 3.1 The pursuit of digital advertising revenue 40 Case Study: A Contemporary Newsroom 43 3.2 Direct payment by consumers 48 3.3 What could be done 53 Chapter 4 – The role of the online platforms in the markets for news and advertising 57 Introduction 57 4.1 The online advertising market 58 4.2 The distribution of news publishers’ content online 65 4.3 What could be done? 72 Cairncross Review | 2 Chapter 5 – A future for public interest news 76 5.1 The digital transition has undermined the provision of public-interest journalism 77 5.2 What are publishers already doing to sustain the provision of public-interest news? 78 5.3 The challenges to public-interest journalism are most acute at the local level 79 5.4 What could be done? 82 Conclusion 88 Chapter 6 – What should be done? 90 Endnotes 103 Appendix A: Terms of Reference 114 Appendix B: Advisory Panel 116 Appendix C: Review Methodology 120 Appendix D: List of organisations met during the Review 121 Appendix E: Review Glossary 123 Appendix F: Summary of the Call for Evidence 128 Introduction 128 Appendix G: Acknowledgements 157 Cairncross Review | 3 Executive Summary Executive Summary “The full importance of an epoch-making idea is But the evidence also showed the difficulties with often not perceived in the generation in which it recommending general measures to support is made.. -

Insight Trudeau Without Cheers Assessing 10 Years of Intergovernmental Relations

IRPP Harper without Jeers, Insight Trudeau without Cheers Assessing 10 Years of Intergovernmental Relations September 2016 | No. 8 Christopher Dunn Summary ■■ Stephen Harper’s approach to intergovernmental relations shifted somewhat from the “open federalism” that informed his initial years as prime minister toward greater multilateral engagement with provincial governments and certain unilateral moves. ■■ Harper left a legacy of smaller government and greater provincial self-reliance. ■■ Justin Trudeau focuses on collaboration and partnership, including with Indigenous peoples, but it is too early to assess results. Sommaire ■■ En matière de relations intergouvernementales, l’approche de Stephen Harper s’est progressivement éloignée du « fédéralisme ouvert » de ses premières années au pouvoir au profit d’un plus fort engagement multilatéral auprès des provinces, ponctué ici et là de poussées d’unilatéralisme. ■■ Gouvernement réduit et autonomie provinciale accrue sont deux éléments clés de l’héritage de Stephen Harper. ■■ Justin Trudeau privilégie la collaboration et les partenariats, y compris avec les peuples autochtones, mais il est encore trop tôt pour mesurer les résultats de sa démarche. WHAT HAS HAPPENED TO INTERGOVERNMENTAL RELATIONS IN CANADA? Surprises. In October 2015, we had an election with a surprise ending. The Liberal Party, which had been third in the polls for months, won a clear majority. The new prime minister, Justin Trudeau, provided more surprises, engaging in a whirl- wind of talks with first ministers as a group and with social partners that the previous government, led by Stephen Harper, had largely ignored. He promised a new covenant with Indigenous peoples, the extent of which surprised even them. Change was in the air. -

Macron Leaks” Operation: a Post-Mortem

Atlantic Council The “Macron Leaks” Operation: A Post-Mortem Jean-Baptiste Jeangène Vilmer The “Macron Leaks” Operation: A Post-Mortem Jean-Baptiste Jeangène Vilmer ISBN-13: 978-1-61977-588-6 This report is written and published in accordance with the Atlantic Council Policy on Intellectual Indepen- dence. The author is solely responsible for its analysis and recommendations. The Atlantic Council and its donors do not determine, nor do they necessarily endorse or advocate for, any of this report’s conclusions. June 2019 Contents Acknowledgments iv Abstract v Introduction 1 I- WHAT HAPPENED 4 1. The Disinformation Campaign 4 a) By the Kremlin media 4 b) By the American alt-right 6 2. The Aperitif: #MacronGate 9 3. The Hack 10 4. The Leak 11 5. In Summary, a Classic “Hack and Leak” Information Operation 14 6. Epilogue: One and Two Years Later 15 II- WHO DID IT? 17 1. The Disinformation Campaign 17 2. The Hack 18 3. The Leak 21 4. Conclusion: a combination of Russian intelligence and American alt-right 23 III- WHY DID IT FAIL AND WHAT LESSONS CAN BE LEARNED? 26 1. Structural Reasons 26 2. Luck 28 3. Anticipation 29 Lesson 1: Learn from others 29 Lesson 2: Use the right administrative tools 31 Lesson 3: Raise awareness 32 Lesson 4: Show resolve and determination 32 Lesson 5: Take (technical) precautions 33 Lesson 6: Put pressure on digital platforms 33 4. Reaction 34 Lesson 7: Make all hacking attempts public 34 Lesson 8: Gain control over the leaked information 34 Lesson 9: Stay focused and strike back 35 Lesson 10: Use humor 35 Lesson 11: Alert law enforcement 36 Lesson 12: Undermine propaganda outlets 36 Lesson 13: Trivialize the leaked content 37 Lesson 14: Compartmentalize communication 37 Lesson 15: Call on the media to behave responsibly 37 5. -

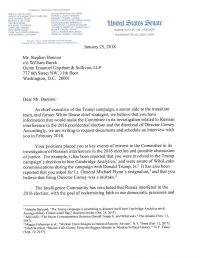

Ilnitnt ~Tares ~Cnetc JEFF FLAKE

CHARLES E. GRASSLEY, IOWA, CHAIRMAN ORRIN G. HATCH, UTAH DIANNE FEINSTEIN. CALIFORNIA LINDSEY O GRAHAM, SOUTH CAROLINA PATRICK J LEAHY. VERMONT JOHN CORNYN, TEXAS RICHARD J DURBIN, ILLINOIS MICHAELS. LEE, UTAH SHELDON WHITEHOUSE, RHODE ISLAND TED CRUZ, TEXAS AMY KLOBUCHAR, MINNESOTA BEN SASSE. NEBRASKA CHRISTOPHER A . COONS, DELAWARE ilnitnt ~tares ~cnetc JEFF FLAKE. ARIZONA RICHARD BLUMENTHAL, CONNECTICUT MIKE CRAPO, IDAHO MAZIE K. HIRONO. HAWAII COMMITIEE ON THE JUDICIARY THOM TILLIS, NORTH CAROLINA CORY A. BOOKER, NEW JERSEY JOHN KENNEDY. LOUISIANA KAMALA D. HARRIS, CALIFORNIA WASHINGTON, DC 20510-6275 KoLAN L DAVIS, Ch,ef Counsel and Staff O,rector JENNIFER DUCK, Oemocrat,c Chief Counsel and Staff Director January 25, 2018 Mr. Stephen Bannon c/o William Burck Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, LLP 777 6th Street NW, I Ith floor Washington, D.C. 20001 Dear Mr. Bannon: As chief executive of the Trump campaign, a senior aide to the transition team, and former White House chief strategist, we believe that you have information that would assist the Committee in its investigation related to Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election and the dismissal of Director Corney. Accordingly, we are writing to request documents and schedule an interview with you in February 2018. Your positions placed you at key events of interest to the Committee in its investigation of Russian interference in the 2016 election and possible obstruction ofjustice . For example, it has been reported that you were involved in the Trump campaign's decision to hire Cambridge Analytica, 1 and were aware of WikiLeaks communications during the campaign with Donald Trump, Jr. -

Artificial Intelligence: Risks to Privacy and Democracy

Artificial Intelligence: Risks to Privacy and Democracy Karl Manheim* and Lyric Kaplan** 21 Yale J.L. & Tech. 106 (2019) A “Democracy Index” is published annually by the Economist. For 2017, it reported that half of the world’s countries scored lower than the previous year. This included the United States, which was de- moted from “full democracy” to “flawed democracy.” The princi- pal factor was “erosion of confidence in government and public in- stitutions.” Interference by Russia and voter manipulation by Cam- bridge Analytica in the 2016 presidential election played a large part in that public disaffection. Threats of these kinds will continue, fueled by growing deployment of artificial intelligence (AI) tools to manipulate the preconditions and levers of democracy. Equally destructive is AI’s threat to deci- sional and informational privacy. AI is the engine behind Big Data Analytics and the Internet of Things. While conferring some con- sumer benefit, their principal function at present is to capture per- sonal information, create detailed behavioral profiles and sell us goods and agendas. Privacy, anonymity and autonomy are the main casualties of AI’s ability to manipulate choices in economic and po- litical decisions. The way forward requires greater attention to these risks at the na- tional level, and attendant regulation. In its absence, technology gi- ants, all of whom are heavily investing in and profiting from AI, will dominate not only the public discourse, but also the future of our core values and democratic institutions. * Professor of Law, Loyola Law School, Los Angeles. This article was inspired by a lecture given in April 2018 at Kansai University, Osaka, Japan.