Towards a Poetics of the Mental Health Play

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Helen Kluger Playwright

Helen Kluger Playwright Agents Nicki Stoddart [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0869 Credits Theatre Production Company Notes THE DACHA Glasgow Lunchtime Theatre directed by Philip Howard BETTER IN MY DREAMS Waterman's Arts Centre, Brentford Dir: Sylvia Syms HONEY, YOU'RE TALKING New End Theatre, Hampstead, Kings Co-written with THROUGH YOUR HAT! Head and Salisbury Playhouse Elizabeth Romilly SWEET POUNDS OF FLESH Performed at The Arts Theatre Club TABLE HOPPING AT JOE'S Performed at the IVC, Covent Garden Co-written with Gary Lyons Radio Production Company Notes FOOTBALLERS' WIVES Radio 4 Dir: Jeremy Mortimer WE WHO SERVE Radio 4 Dir: Jeremy Mortimer FIFTEEN LOVE Radio 5 Co-written with Gillian Bevan and Tessa Peake- Jones Dir: Sally Avens SYNCHRO Radio 4 Dir: Jeremy Mortimer NO RIGHTS, ONLY Radio 4 Co-written with Gillian Bevan and Tessa Peake- WRONG Jones Dir: Lesley Manning An Independent Tight Assets Theatre Production United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes RUKULIBAM World Service Dir: Gordon House "Independent" newspaper choice of "95". Bronze award winner in The New York Festivals. ONE DAY, I'LL FLY AWAY Radio 4 Dir: Sally Avens PASSIONATE PLAYING World Service Dir: Gordon House HOLDING HANDS Radio 4 Dir: Tessa Peake-Jones Starring Barbara Leigh-Hunt and Richard Pasco. FUNNY BONES Radio 4 Dir: Marilyn Imrie ON THE ROCKS Radio 4 Dir: Pauline Harris LONELY HEARTS Radio 4 Dir: Sally Avens THE DACHA Radio 4 Dir: Gemma Jenkins THE SISTER OF DEATH Radio 4 Dir: Sally Avens GOOSE A thriller written for Dir: Celia de Wollf the Internet Starring Imelda Staunton as Janet and Tessa Peake-Jones as Margaret. -

Historical Critique Or Transcendental Critique in Foucault: Two Kantian Lineages Colin Koopman, University of Oregon

Colin Koopman 2010 ISSN: 1832-5203 Foucault Studies, No. 8, pp. 100-121, February 2010 ARTICLE Historical Critique or Transcendental Critique in Foucault: Two Kantian Lineages Colin Koopman, University of Oregon ABSTRACT: A growing body of interpretive literature concerning the work of Michel Foucault asserts that Foucault’s critical project is best interpreted in light of various strands of philosophical phenomenology. In this article I dispute this interpretation on both textual and philosophical grounds. It is shown that a core theme of ‘the phenomenological Foucault’ having to do with transcendental inquiry cannot be sustained by a careful reading of Foucault’s texts nor by a careful interpretation of Foucault’s philosophical commitments. It is then shown that this debate in Foucault scholarship has wider ramifications for understanding ‘the critical Foucault’ and the relationship of Foucault’s projects to Kantian critical philosophy. It is argued that Foucault’s work is Kantian at its core insofar as it institutes a critical inquiry into conditions of possibility. But whereas critique for Kant was transcendental in orientation, in Foucault critique becomes historical, and is much the better for it. Keywords: Michel Foucault, Critique, Immanuel Kant, Phenomenology, Transcen- dental Critique. 100 Koopman: Historical Critique or Transcendental Crititique in Foucault ‚You seem to me Kantian or Husserlian. In all of my work I strive instead to avoid any reference to this transcendental as a condition of the possibility for any knowledge. When I say that I strive to avoid it, I don’t mean that I am sure of succeeding< I try to historicize to the utmost to leave as little space as possible to the transcendental. -

What Ever Happened to In-Yer-Face Theatre?

What Ever Happened to in-yer-face theatre? Aleks SIERZ (Theatre Critic and Visiting Research Fellow, Rose Bruford College) “I have one ambition – to write a book that will hold good for ten years afterwards.” Cyril Connolly, Enemies of Promise • Tuesday, 23 February 1999; Brixton, south London; morning. A Victorian terraced house in a road with no trees. Inside, a cloud of acrid dust rises from the ground floor. Two workmen are demolishing the wall that separates the dining room from the living room. They sweat; they curse; they sing; they laugh. The floor is covered in plaster, wooden slats, torn paper and lots of dust. Dust hangs in the air. Upstairs, Aleks is hiding from the disruption. He is sitting at his desk. His partner Lia is on a train, travelling across the city to deliver a lecture at the University of East London. Suddenly, the phone rings. It’s her. And she tells him that Sarah Kane is dead. She’s just seen the playwright’s photograph in the newspaper and read the story, straining to see over someone’s shoulder. Aleks immediately runs out, buys a newspaper, then phones playwright Mark Ravenhill, a friend of Kane’s. He gets in touch with Mel Kenyon, her agent. Yes, it’s true: Kane, who suffered from depression for much of her life, has committed suicide. She is just twenty-eight years old. Her celebrity status, her central role in the history of contemporary British theatre, is attested by the obituaries published by all the major newspapers. Aleks returns to his desk. -

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 19 – 25 August 2017 Page 1 of 8

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 19 – 25 August 2017 Page 1 of 8 SATURDAY 19 AUGUST 2017 Read by Robert Glenister monarchy and giving a glimpse into the essential ingredients of a Written by Sarah Dunant successful sovereign. SAT 00:00 Bruce Bedford - The Gibson (b007js93) Abridged by Eileen Horne In this programme, Will uses five objects to investigate a pivotal Episode 5Saul and Elise make a grim discovery in the nursing Produced by Clive Brill aspect of the art of monarchy - the projection of magnificence. An home. Time-hopping thriller with Robert Glenister and Freddie A Pacificus production for BBC Radio 4. idea as old as monarchy itself, magnificence is the expression of Jones. SAT 02:15 Me, My Selfie and I: Aimee Fuller©s Generation power through the display of wealth and status. Will©s first object SAT 00:30 Soul Music (b04nrw25) Game (b06172qq) unites our current Queen with George III; the Gold State Coach, Series 19, A Shropshire Lad"Into my heart an air that kills Episode 5In the final part of her exploration of the selfie which has been used for coronations since 1821. Built for George From yon far country blows: phenomenon, snowboarder Aimee Fuller describes how she will III in 1762, it reflects Britain©s new found glory in its richly gilded What are those blue remembered hills, be using social media as she sets out to compete for a place at the carvings and painted panels...but the glory was to be short lived. What spires, what farms are those? next Winter Olympics. -

Hilary Mantel Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8gm8d1h No online items Hilary Mantel Papers Finding aid prepared by Natalie Russell, October 12, 2007 and Gayle Richardson, January 10, 2018. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © October 2007 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Hilary Mantel Papers mssMN 1-3264 1 Overview of the Collection Title: Hilary Mantel Papers Dates (inclusive): 1980-2016 Collection Number: mssMN 1-3264 Creator: Mantel, Hilary, 1952-. Extent: 11,305 pieces; 132 boxes. Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: The collection is comprised primarily of the manuscripts and correspondence of British novelist Hilary Mantel (1952-). Manuscripts include short stories, lectures, interviews, scripts, radio plays, articles and reviews, as well as various drafts and notes for Mantel's novels; also included: photographs, audio materials and ephemera. Language: English. Access Hilary Mantel’s diaries are sealed for her lifetime. The collection is open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. The responsibility for identifying the copyright holder, if there is one, and obtaining necessary permissions rests with the researcher. -

Theatre in England 2011-2012 Harlingford Hotel Phone: 011-442

English 252: Theatre in England 2011-2012 Harlingford Hotel Phone: 011-442-07-387-1551 61/63 Cartwright Gardens London, UK WC1H 9EL [*Optional events — seen by some] Wednesday December 28 *1:00 p.m. Beauties and Beasts. Retold by Carol Ann Duffy (Poet Laureate). Adapted by Tim Supple. Dir Melly Still. Design by Melly Still and Anna Fleischle. Lighting by Chris Davey. Composer and Music Director, Chris Davey. Sound design by Matt McKenzie. Cast: Justin Avoth, Michelle Bonnard, Jake Harders, Rhiannon Harper- Rafferty, Jack Tarlton, Jason Thorpe, Kelly Williams. Hampstead Theatre *7.30 p.m. Little Women: The Musical (2005). Dir. Nicola Samer. Musical Director Sarah Latto. Produced by Samuel Julyan. Book by Peter Layton. Music and Lyrics by Lionel Siegal. Design: Natalie Moggridge. Lighting: Mark Summers. Choreography Abigail Rosser. Music Arranger: Steve Edis. Dialect Coach: Maeve Diamond. Costume supervisor: Tori Jennings. Based on the book by Louisa May Alcott (1868). Cast: Charlotte Newton John (Jo March), Nicola Delaney (Marmee, Mrs. March), Claire Chambers (Meg), Laura Hope London (Beth), Caroline Rodgers (Amy), Anton Tweedale (Laurie [Teddy] Laurence), Liam Redican (Professor Bhaer), Glenn Lloyd (Seamus & Publisher’s Assistant), Jane Quinn (Miss Crocker), Myra Sands (Aunt March), Tom Feary-Campbell (John Brooke & Publisher). The Lost Theatre (Wandsworth, South London) Thursday December 29 *3:00 p.m. Ariel Dorfman. Death and the Maiden (1990). Dir. Peter McKintosh. Produced by Creative Management & Lyndi Adler. Cast: Thandie Newton (Paulina Salas), Tom Goodman-Hill (her husband Geraldo), Anthony Calf (the doctor who tortured her). [Dorfman is a Chilean playwright who writes about torture under General Pinochet and its aftermath. -

Fleabag’ from London’S West End Expands Distribution in U.S

MEDIA ALERT – September 20, 2019 ‘Fleabag’ from London’s West End Expands Distribution in U.S. Cinemas Monday, November 18 for One Night See the critically acclaimed, award-winning one woman show that inspired the network series with BAFTA winner and Emmy nominee Phoebe Waller-Bridge • WHAT: Fathom Events, BY Experience and National Theatre Live release “Fleabag” in cinemas on Monday, November 18, 2019 at 7:00 p.m. local time, captured live from Wyndham’s Theatre London during its sell out West End run. • WHERE: Tickets for these events can be purchased online by visiting www.FathomEvents.com or at participating theater box offices. Fans throughout the U.S. will be able to enjoy the events in nearly 500 movie theaters through Fathom’s Digital Broadcast Network (DBN). For a complete list of theater locations visit the Fathom Events website (theaters and participants are subject to change). • WHO: Fathom Events, BY Experience and National Theatre Live “Filthy, funny, snarky and touching” Daily Telegraph “Witty, filthy and supreme” The Guardian “Gloriously Disruptive. Phoebe Waller-Bridge is a name to reckon with” The New York Times Fleabag Written by Phoebe Waller-Bridge and directed by Vicky Jones, Fleabag is a rip-roaring look at some sort of woman living her sort of life. Fleabag may appear emotionally unfiltered and oversexed, but that’s just the tip of the iceberg. With family and friendships under strain and a guinea pig café struggling to keep afloat, Fleabag suddenly finds herself with nothing to lose. Fleabag was adapted into a BBC Three Television series in partnership with Amazon Prime Video in 2016 and earned Phoebe a BAFTA Award for Best Female Comedy Performance. -

A Study of the Royal Court Young Peoples’ Theatre and Its Development Into the Young Writers’ Programme

Building the Engine Room: A Study of the Royal Court Young Peoples’ Theatre and its Development into the Young Writers’ Programme N O Holden Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Building the Engine Room: A Study of the Royal Court’s Young Peoples’ Theatre and its Development into the Young Writers’ Programme Nicholas Oliver Holden, MA, AKC A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Lincoln for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Fine and Performing Arts College of Arts March 2018 2 DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for a higher degree elsewhere. 3 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisors: Dr Jacqueline Bolton and Dr James Hudson, who have been there with advice even before this PhD began. I am forever grateful for your support, feedback, knowledge and guidance not just as my PhD supervisors, but as colleagues and, now, friends. Heartfelt thanks to my Director of Studies, Professor Mark O’Thomas, who has been a constant source of support and encouragement from my years as an undergraduate student to now as an early career academic. To Professor Dominic Symonds, who took on the role of my Director of Studies in the final year; thank you for being so generous with your thoughts and extensive knowledge, and for helping to bring new perspectives to my work. My gratitude also to the University of Lincoln and the School of Fine and Performing Arts for their generous studentship, without which this PhD would not have been possible. -

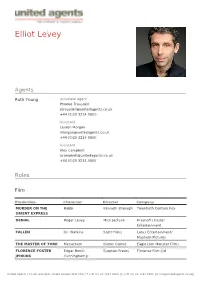

Elliot Levey

Elliot Levey Agents Ruth Young Associate Agent Phoebe Trousdell [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0800 Assistant Lauren Morgan [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0800 Assistant Alex Campbell [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0800 Roles Film Production Character Director Company MURDER ON THE Rabbi Kenneth Branagh Twentieth Century Fox ORIENT EXPRESS DENIAL Roger Levey Mick Jackson Krasnoff / Foster Entertainment FALLEN Dr. Watkins Scott Hicks Lotus Entertainment/ Mayhem Pictures THE MASTER OF YORK Menachem Kieron Quirke Eagle Lion Monster Films FLORENCE FOSTER Edgar Booth Stephen Frears Florence Film Ltd JENKINS Cunningham Jr United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company THE LADY IN THE VAN Director Nicholas Hytner Van Production Ltd. SPOOKS Philip Emmerson Bharat Nalluri Shine Pictures & Kudos PHILOMENA Alex Stephen Frears Lost Child Limited THE WALL Stephen Cam Christiansen National film Board of Canada THE QUEEN Stephen Frears Granada FILTH AND WISDOM Madonna HSI London SONG OF SONGS Isaac Josh Appignanesi AN HOUR IN PARADISE Benjamin Jan Schutte BOOK OF JOHN Nathanael Philip Saville DOMINOES Ben Mirko Seculic JUDAS AND JESUS Eliakim Charles Carner Paramount QUEUES AND PEE Ben Despina Catselli Pinhead Films JASON AND THE Canthus Nick Willing Hallmark ARGONAUTS JESUS Tax Collector Roger Young Andromeda Prods DENIAL Roger Levey Denial LTD Television Production Character Director Company -

The Children by Lucy Kirkwood

THE CHILDREN BY LUCY KIRKWOOD DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. THE CHILDREN Copyright © 2018, Lucy Kirkwood All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of THE CHILDREN is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Com- monwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan-American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of me- chanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for THE CHILDREN are controlled exclusively by Dramatists Play Service, Inc., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No professional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of Dramatists Play Service, Inc., and paying the requisite fee. Inquiries concerning all other rights should be addressed to Casarotto Ramsay & Associates Ltd, Waverley House, 7-12 Noel Street, London, W1F 8GQ. -

The Old-Timer

The Old-Timer produced by www.prewarboxing.co.uk Number 1. August 2007 Sid Shields (Glasgow) – active 1911-22 This is the first issue of magazine will concentrate draw equally heavily on this The Old-Timer and it is my instead upon the lesser material in The Old-Timer. intention to produce three lights, the fighters who or four such issues per year. were idols and heroes My prewarboxing website The main purpose of the within the towns and cities was launched in 2003 and magazine is to present that produced them and who since that date I have historical information about were the backbone of the directly helped over one the many thousands of sport but who are now hundred families to learn professional boxers who almost completely more about their boxing were active between 1900 forgotten. There are many ancestors and frequently and 1950. The great thousands of these men and they have helped me to majority of these boxers are if I can do something to learn a lot more about the now dead and I would like preserve the memory of a personal lives of these to do something to ensure few of them then this boxers. One of the most that they, and their magazine will be useful aspects of this exploits, are not forgotten. worthwhile. magazine will be to I hope that in doing so I amalgamate boxing history will produce an interesting By far the most valuable with family history so that and informative magazine. resource available to the the articles and features The Old-Timer will draw modern boxing historian is contained within are made heavily on the many Boxing News magazine more interesting. -

Blanche Mcintyre Director / Writer

Blanche McIntyre Director / Writer * Winner - Best Director: TMA 2013 UK Theatre Awards * Winner of the 2011 Critcs' Circle Most Promising Newcomer Award for ACCOLADE and FOXFINDER (both at the Finborough Theatre) * FOXFINDER: Listed in Independent's top 5 picks for 2011 * ACCOLADE: Best Director and Best Production at Off West End Theatre Awards 2011; Listed in the Spectator's Top Ten Plays for 2011; Time Out's Best Fringe Show 2011 National Theatre Studio Director's Course (2010) Winner - Leverhulme Bursary (2009) Agents Giles Smart Assistant Ellie Byrne [email protected] +44 (020 3214 0812 Credits In Development Production Company Notes THE LITTLE FOXES Gate Theatre, Dublin By Lillian Hellman 2020 Theatre Production Company Notes HYMN Almeida / Sky Arts By Lolita Chakrabarti 2021 United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes BOTTICELLI IN THE FIRE Hampstead By Jordan Tannahill 2019 BARTHOLOMEW FAIR Shakespeare's Globe - By Ben Jonson 2019 Sam Wanamaker Playhouse TARTUFFE National Theatre By Molière 2019 Adapted by John Donnelly & Director Blanche McIntyre WOMEN IN POWER Nuffield Based on Aristophanes' 2018 ASSEMBLY WOMEN THE WINTER'S TALE Shakespeare's Globe By William Shakespeare 2018 THE WRITER Almeida By Ella Hickson 2018 TITUS ANDRONICUS RSC By William Shakespeare 2017 THE NORMAN CONQUESTS Chichester Festival By Alan Ayckbourn 2017 Theatre THE TWO NOBLE KINSMEN RSC: The Swan By William Shakespeare 2016 NOISES