Provenance 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federation Teacher Notes

Government of Western Australia Department of the Premier and Cabinet Constitutional Centre of WA Federation Teacher Notes Overview The “Federation” program is designed specifically for Year 6 students. Its aim is to enhance students’ understanding of how Australia moved from having six separate colonies to become a nation. In an interactive format students complete a series of activities that include: Discussing what Australia was like before 1901 Constructing a timeline of the path to Federation Identifying some of the founding fathers of Federation Examining some of the federation concerns of the colonies Analysing the referendum results Objectives Students will: Discover what life was like in Australia before 1901 Explain what Federation means Find out who were our founding fathers Compare and contrast some of the colony’s concerns about Federation Interpret the results of the 1899 and 1900 referendums Western Australian Curriculum links Curriculum Code Knowledge & Understandings Year 6 Humanities and Social Sciences (HASS) ACHASSK134 Australia as a Nation Key figures (e.g. Henry Parkes, Edmund Barton, George Reid, John Quick), ideas and events (e.g. the Tenterfield Oration, the Corowa Conference, the referendums) that led to Australia's Federation and Constitution, including British and American influences on Australia's system of law and government (e.g. Magna Carta, federalism, constitutional monarchy, the Westminster system, the Houses of Parliament) Curriculum links are taken from: https://k10outline.scsa.wa.edu.au/home/p-10-curriculum/curriculum-browser/humanities-and-social- sciences Background information for teachers What is Federation? (in brief) Federation is the bringing together of colonies to form a nation with a federal (national) government. -

Western Australian War Memorials Western Australian Wwii Roll of Honour

LEST WE FORGET WESTERN AUSTRALIAN WAR MEMORIALS WESTERN AUSTRALIAN WWII ROLL OF HONOUR The World War II Roll of Honour for Men and Women who enlisted from Western Australia is shown on the Undercroft of the WA State War Memorial in Kings Park, Perth. The names are shown by Service and then in alphabetical order on a series of Plaques that were unveiled on Sunday 6 November 1955. This document shows those names combined and arranged by the local Roll of Honour provided on the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) WWII Nominal Roll, or where no Roll is given, by place of Birth. This document also shows the Indigenous Roll of Honour, the Merchant Navy Roll of Honour and the Roll of Honour for Airmen from Western Australia who died while in Service with Commonwealth Air Forces. In addition, this document shows the list of Service Members who are shown on the WA Memorial, but who do not qualify for the National Roll of Honour maintained by the Australian War Memorial (AWM). This document can be searched by text and is bookmarked for ease of navigation. Further biographical and Service information for each Service Member may be found on the National Archives of Australia, the AWM, the Commonwealth Graves Commission, and the DVA Websites. -

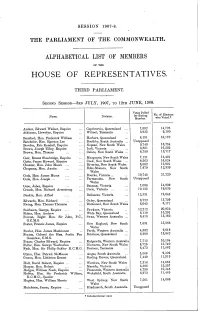

House of Representatives

SESSION 1907-8. THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH. ALPHABETICAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. THIRD PARLIAMENT. SECOND SESSION-3RD JULY, 1907, TO 12TH JUNE, 1908. Votes Polled No. of Electors Name. Division. for Sitting Member. who Voted.* Archer, Edward Walker, Esquire Capricornia, Queensland ... 7,892 14,725 Atkinson, Llewelyn, Esquire Wilmot, Tasmania 3,935 9,100 Bamford, Hon. Frederick William Herbert, Queensland ... 8,151 16,170 Batchelor, Hon. Egerton Lee Boothby, South Australia ... Unopposed Bowden, Eric Kendall, Esquire Nepean, New South Wales 9,749 16,754 Brown, Joseph Tilley, Esquire Indi, Victoria 6,801 16,205 Brown, Hon. Thomas ... Calare, New South Wales ... 6,759 13,717 Carr, Ernest Shoobridge, Esquire Macquarie, New South Wales 7,121 14,401 Catts, James Howard, Esquire Cook, New South Wales .. 8,563 16,624 Chanter, Hon. John Moore ... Riverina, New South Wales 6,662 12,921 Chapman, Hon. Austin ... Eden-Monaro, New South 7,979 12,339 Wales Cook, Hon. James Hume ... Bourke, Victoria ... 10,745 21,220 Cook, Hon. Joseph ... Parramatta, New South Unopposed Wales Coon, Jabez, Esquire Batman, Victoria 7,098 14,939 Crouch, Hon. Richard Armstrong Corio, Victoria ... 10,135 19,035 Deakin, Hon. Alfred Ballaarat, Victoria 12,331 19,048 Edwards, Hon. Richard Oxley, Queensland 8,722 13,729 8,171 Ewing, Hon. Thomas Thomson Richmond, New South Wales 6,042 Fairbairn, George, Esquire ... Fawkner, Victoria 12,212 20,952 Fisher, Hon. Andrew ... Wide Bay, Queensland 8,118 15,291 Forrest, Right Hon. Sir John, P.C., Swan, Western Australia ... 8,418 13,163 G.C.M.G. -

How Federal Theory Supports States' Rights Michelle Evans

The Western Australian Jurist Vol. 1, 2010 RETHINKING THE FEDERAL BALANCE: HOW FEDERAL THEORY SUPPORTS STATES’ RIGHTS MICHELLE EVANS* Abstract Existing judicial and academic debates about the federal balance have their basis in theories of constitutional interpretation, in particular literalism and intentionalism (originalism). This paper seeks to examine the federal balance in a new light, by looking beyond these theories of constitutional interpretation to federal theory itself. An examination of federal theory highlights that in a federal system, the States must retain their powers and independence as much as possible, and must be, at the very least, on an equal footing with the central (Commonwealth) government, whose powers should be limited. Whilst this material lends support to intentionalism as a preferred method of constitutional interpretation, the focus of this paper is not on the current debate of whether literalism, intentionalism or the living constitution method of interpretation should be preferred, but seeks to place Australian federalism within the broader context of federal theory and how it should be applied to protect the Constitution as a federal document. Although federal theory is embedded in the text and structure of the Constitution itself, the High Court‟s generous interpretation of Commonwealth powers post-Engineers has led to increased centralisation to the detriment of the States. The result is that the Australian system of government has become less than a true federation. I INTRODUCTION Within Australia, federalism has been under attack. The Commonwealth has been using its financial powers and increased legislative power to intervene in areas of State responsibility. Centralism appears to be the order of the day.1 Today the Federal landscape looks very different to how it looked when the Australian Colonies originally „agreed to unite in one indissoluble Federal Commonwealth‟2, commencing from 1 January 1901. -

The Deakinite Myth Exposed Other Accounts of Constitution-Makers, Constitutions and Citizenship

The Deakinite Myth Exposed Other accounts of constitution-makers, constitutions and citizenship This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University 2005 Geoffrey Trenorden BA Honours (Murdoch) Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. …………………………………….. Geoffrey Trenorden ii Abstract As argued throughout this thesis, in his personification of the federal story, if not immediately in his formulation of its paternity, Deakin’s unpublished memoirs anticipated the way that federation became codified in public memory. The long and tortuous process of federation was rendered intelligible by turning it into a narrative set around a series of key events. For coherence and dramatic momentum the narrative dwelt on the activities of, and words of, several notable figures. To explain the complex issues at stake it relied on memorable metaphors, images and descriptions. Analyses of class, citizenship, or the industrial confrontations of the 1890s, are given little or no coverage in Deakinite accounts. Collectively, these accounts are told in the words of the victors, presented in the images of the victors, clothed in the prejudices and predilections of the victors, while the losers are largely excluded. Those who spoke out against or doubted the suitability of the constitution, for whatever reason, have largely been removed from the dominant accounts of constitution-making. More often than not they have been ‘character assassinated’ or held up to public ridicule by Alfred Deakin, the master narrator of the Conventions and federation movement and by his latter-day disciples. -

The Governor–General

CHAPTER V THE GOVERNOR-GENERALO, A MOST punctilious, prompt and copious correspondent was Sir Ronald Munro-Ferguson, who presided over the Govern- ment of the Commonwealth from 1914 to 1920. His tall. perpendicular script was familiar to a host of friends in many countries, and his official letters to His Majesty the King and the four Secretaries of State during his period-Mr. Lewis Harcourt, Mr. Walter Long,2 Mr. Bonar Law3 and Lord hlilner'-would, if printed, fill several substantial volumes. His habit was to write even the longest letters with his own hand, for he had served his apprenticeship to official life in the Foreign Office at a period when the typewriter was still a new-fangled invention. He rarely dictated correspondence, but he kept typed copies of all important letters, and, being bq nature and training extremely orderly, filed them in classified, docketed packets. He was disturbed if a paper got out of its proper place. He wrote to Sir John Quick! part author oi Quick and Garran's well-known commentary on the Com- monwealth Constitution, warning him that the documents relating to the double dissolution, printed as a parliamentary paper on the 8th of October, 1914, were arranged in the wrong order. Such a fault, or anything like slovenliness or negligence in the transaction and record of official business, brought forth a gentle, but quite significant, reproof. In respect to business method, the Governor-General was one of the best trained public servants in the Commonwealth during the war years. - - 'This chapter is based upon the Novar papers at Raith. -

The Crown & Kangaroo Victorian Colonial Flags

The Crown & Kangaroo Victorian Colonial Flags. Copyright © John Rogers 2012 After separating from New South Wales in 1851, the Colony of Victoria lacked a distinctive flag to indicate that its vessels belonged to a the colony of Victoria. It has previously been believed that this state of affairs continued until 1870 when a Victorian flag was available for flying from the colony’s vessels. The research detailed below indicates that two types of official Victorian flags were in use prior to 1870. It would appear that history had simply forgotten about them. Inauguration of the Victorian Flags in 1870 On the 9th of February 1870 Her Majesty’s Victorian Ship (HMVS) Nelson and the reformatory Ship, Sir Harry Smith fired a 21 gun salute. The occasion was the unfurling of the new blue Victorian Government flag and new red Victorian Merchant flag on board the ex-Line-of-Battleship HMVS Nelson . Described by The Argus 1 newspaper as an event of some importance, the Naval & Military Gazette 2 pointed out that the new (government) flag was “adopted at the suggestion of the Admiralty to distinguish the vessels of the Victorian Navy”. This 1870 Victorian flag was very similar to the current Australian flag. Naturally, being prior to federation, the 1870 flag did not include the federation star and unlike the current Australian flag, the stars of the Southern Cross on the Victorian flag had, and still have, five, six, seven, eight and nine points. The 1870 flag soon evolved into the 1877 flag when the size of the Southern Cross was reduced and an imperial crown added above it. -

COMMONWEALTH PARLIAMENT Ca Paper Prepared by Sir John Kirwan and Read to the IVA

6 WESTERN AUSTRALIAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY Tke First COMMONWEALTH PARLIAMENT cA Paper prepared by Sir john Kirwan and read to the IVA. Historical Soci'ely on 27tlt September, /946. HE first Prime Minister of Australia, the Smith, Alexander Percival Matheson, George Right Honourable Sir Edmund Barton, Pearce, Hugh de Largie, Edward Harney and T formed his Government on 1st January, Norman Ewing. Senator Ewing resigned 1901. By that time the Commonwealth Con from the Senate in April, 1903, and H. J. stitution had been accepted by the votes of Saunders wa selected to fill the vacancy at a majority of the electors in all the six a joint sitting of the State Parliament- colonies, the Imperial Parliament had passed the necessary legislation and the essential Of these eleven members, Sir John Forrest proclamation had been signed by Her was the only one with notable or extended Majesty, Queen Victoria. parliamentary experience. He already had a distinguished career as an explorer, also he The result of the referendum, in West had worthily filled various public offices and Australia was 44,BOO in favour of federal had been Premier for more than ten years. union and 19,691 against, the majority being Of the others, Mr. Solomon and Mr. Ewing more than two to one, Perth and Fremantle had sat for some years in the Legislative gave substantial majorities for federation and Assembly and Mr. Saunders in the Legisla on the Goldfields the Yes vote was 15 to one. tive Council. Staniforth Smith at the time of his election for the Senate, was Mayor of I had taken a prominent part in further Kalgoorlie. -

The Constitutional Conventions and Constitutional Change: Making Sense of Multiple Intentions

Harry Hobbs and Andrew Trotter* THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTIONS AND CONSTITUTIONAL CHANGE: MAKING SENSE OF MULTIPLE INTENTIONS ABSTRACT The delegates to the 1890s Constitutional Conventions were well aware that the amendment mechanism is the ‘most important part of a Cons titution’, for on it ‘depends the question as to whether the state shall develop with peaceful continuity or shall suffer alternations of stagnation, retrogression, and revolution’.1 However, with only 8 of 44 proposed amendments passed in the 116 years since Federation, many commen tators have questioned whether the compromises struck by the delegates are working as intended, and others have offered proposals to amend the amending provision. This paper adds to this literature by examining in detail the evolution of s 128 of the Constitution — both during the drafting and beyond. This analysis illustrates that s 128 is caught between three competing ideologies: representative and respons ible government, popular democracy, and federalism. Understanding these multiple intentions and the delicate compromises struck by the delegates reveals the origins of s 128, facilitates a broader understanding of colonial politics and federation history, and is relevant to understanding the history of referenda as well as considerations for the section’s reform. I INTRODUCTION ver the last several years, three major issues confronting Australia’s public law framework and a fourth significant issue concerning Australia’s commitment Oto liberalism and equality have been debated, but at an institutional level progress in all four has been blocked. The constitutionality of federal grants to local government remains unresolved, momentum for Indigenous recognition in the Constitution ebbs and flows, and the prospects for marriage equality and an * Harry Hobbs is a PhD candidate at the University of New South Wales Faculty of Law, Lionel Murphy postgraduate scholar, and recipient of the Sir Anthony Mason PhD Award in Public Law. -

Founding Families of Ipswich Pre 1900: M-Z

Founding Families of Ipswich Pre 1900: M-Z Name Arrival date Biographical details Macartney (nee McGowan), Fanny B. 13.02.1841 in Ireland. D. 23.02.1873 in Ipswich. Arrived in QLD 02.09.1864 on board the ‘Young England’ and in Ipswich the same year on board the Steamer ‘Settler’. Occupation: Home Duties. Macartney, John B. 11.07.1840 in Ireland. D. 19.03.1927 in Ipswich. Arrived in QLD 02.09.1864 on board the ‘Young England’ and in Ipswich the same year on board the Steamer ‘Settler’. Lived at Flint St, Nth Ipswich. Occupation: Engine Driver for QLD Government Railways. MacDonald, Robina 1865 (Drayton) B. 03.03.1865. D. 27.12.1947. Occupation: Seamstress. Married Alexander 1867 (Ipswich) approx. Fairweather. MacDonald (nee Barclay), Robina 1865 (Moreton Bay) B. 1834. D. 27.12.1908. Married to William MacDonald. Lived in Canning Street, 1865 – approx 26 Aug (Ipswich) North Ipswich. Occupation: Housewife. MacDonald, William 1865 (Moreton Bay) B. 13.04.1837. D. 26.11.1913. William lived in Canning Street, North Ipswich. 1865 – approx 26 Aug (Ipswich) Occupation: Blacksmith. MacFarlane, John 1862 (Australia) B. 1829. John established a drapery business in Ipswich. He was an Alderman of Ipswich City Council in 1873-1875, 1877-1878; Mayor of Ipswich in 1876; a member of Parliament from 1877-1894; a member of a group who established the Woollen Mill in 1875 of which he became a Director; and a member of the Ipswich Hospital Board. John MacFarlane lived at 1 Deebing Street, Denmark Hill and built a house on the corner of Waghorn and Chelmsford Avenue, Denmark Hill. -

Annual Review

LITTLE COMPANY OF MARY HEALTH CARE LIMITED ANNUAL REVIEW Continuing the Mission of the Sisters of the Little Company of Mary 2015/2016 Continuing the Mission of the Sisters of the Little Company of Mary 1 Spirit of Calvary Hospitality Healing Stewardship Being for Others Respect Everyone is welcome. You matter. We care about you. Your family, those who care for you, and the wider community we serve, matter. Your dignity guides and shapes the care we offer you. Your physical, emotional, spiritual, psychological and social needs are important to us. We will listen to you and to those who care for you. We will involve you in your care. We will deliver care tailored to your needs and goals. Your wellbeing inspires us to learn and improve. 2 Continuing the Mission of the Sisters of the Little Company of Mary Growth, Innovation and Integration Our Mission “We bring the healing ministry of Jesus + STEWARDSHIP recognises that as 1885-2016 to those who are sick, dying and in need individuals and as a community all we 131 years ago , six through ‘being for others’: have has been given to us as a gift. It courageous Sisters of The is our responsibility to manage these + In the Spirit of Mary standing by her precious resources effectively, now Little Company of mary Son on Calvary; and for the future. We are responsible Sailed from Naples to + Through the provision of quality, for: striving for excellence, developing Sydney on the SS Liguria. responsive and compassionate health, personal talents, material possessions, Their mission was to care community and aged care services; our environment, and handing on the for the poor,sick and dying. -

NEWSLETTER 58 Secretary/Treasurer Bill Cummings Tel 07 40312888 Email [email protected]

Newsletter of the 56ers Torchbearers Club Inc No 58 March 2017 www.56ers.org.au 1 “56ers Torchbearers Club Inc” PO Box 2148, CAIRNS Q 4870 Committee: Patron Margaret Cochrane President Jim Vallely Tel 07 40532150 Vice President Dennis Stevenson Tel 07 40653223 NEWSLETTER 58 Secretary/Treasurer Bill Cummings Tel 07 40312888 Email [email protected] President’s Comments GREAT ATHLETES OF (early) 20TH CENTURY Greetings once again Club Members and JOHNNY WEISSMULLER Partners. Happy New Year. Weissmuller was born in 1904 at Freidorf in the After quite a busy year in 2016 our radar tells us Kingdom of Hungary now Romania and died in we could be looking at a quieter 12 months. 1984 in Acapulco. His active years were from 1921 to 1930. The highlights of his swimming time As the Athletic Club has kicked off its new season were:- our club will be keeping a keen eye out for young athletes showing exceptional potential as our Amateur Athletics Union 50m freestyle champion previous assisted athletes have continued to 1921, he was unbeaten in 10 years. An Olympic impress on the State and National level. gold medals in the 100m and 400m freestyle in 1924 Olympics and also in the 4x200m relay. He Cairns Athletic Club has been notified they have also won gold in the 100m freestyle event in the been successful with their bid to host the 1928 Olympics at Amsterdam. Australian All Schools Titles in 2018, quite a coup for the city as over 1,000 athletes will compete over a full week. Sydney resident and 56 Torch Bearer, Ralph Schubert, has thrown his hat into the ring to once more compete in the North Queensland Masters Games in late May.