GUIDE to JEWISH KNOWLEDGE for the CENTER PROFESSIONAL Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿavoda Zara By

The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿAvoda Zara By Mira Beth Wasserman A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley in Jewish Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Daniel Boyarin, chair Professor Chana Kronfeld Professor Naomi Seidman Professor Kenneth Bamberger Spring 2014 Abstract The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿAvoda Zara by Mira Beth Wasserman Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel Boyarin, chair In this dissertation, I argue that there is an ethical dimension to the Babylonian Talmud, and that literary analysis is the approach best suited to uncover it. Paying special attention to the discursive forms of the Talmud, I show how juxtapositions of narrative and legal dialectics cooperate in generating the Talmud's distinctive ethics, which I characterize as an attentiveness to the “exceptional particulars” of life. To demonstrate the features and rewards of a literary approach, I offer a sustained reading of a single tractate from the Babylonian Talmud, ʿAvoda Zara (AZ). AZ and other talmudic discussions about non-Jews offer a rich resource for considerations of ethics because they are centrally concerned with constituting social relationships and with examining aspects of human experience that exceed the domain of Jewish law. AZ investigates what distinguishes Jews from non-Jews, what Jews and non- Jews share in common, and what it means to be a human being. I read AZ as a cohesive literary work unified by the overarching project of examining the place of humanity in the cosmos. -

Tevul Yom Chapter 1

Mishna - Mas. Tevul Yom Chapter 1 MISHNAH 1. IF ONE1 HAD COLLECTED DOUGH-OFFERING2 [PORTIONS] WITH THE INTENTION OF SEGREGATING THEM AFTERWARDS AGAIN, BUT IN THE MEANTIME THEY HAD BECOME STUCK TOGETHER,3 BETH SHAMMAI SAY: THEY SERVE AS CONNECTIVES4 IN THE CASE OF A TEBUL YOM. BUT BETH HILLEL SAY: THEY DO NOT SERVE AS CONNECTIVES. PIECES OF DOUGH5 THAT HAD BECOME STUCK TOGETHER, OR LOAVES5 THAT HAD BECOME JOINED, OR A BATTER-CAKE THAT HAD BEEN BAKED ON TOP OF ANOTHER BATTER-CAKE BEFORE IT COULD FORM A CRUST IN THE OVEN, OR IF THERE WAS FROTH6 ON THE WATER THAT WAS BUBBLING, OR THE FIRST SCUM7 THAT RISES WHEN BOILING GROATS OF BEANS, OR THE SCUM OF NEW WINE (R. JUDAH SAYS: ALSO THAT OF RICE) BETH SHAMMAI SAY: ALL SERVE AS CONNECTIVES IN THE CASE OF THE TEBUL YOM. BUT BETH HILLEL SAY: THEY DO NOT SERVE AS CONNECTIVES.8 THEY9 CONCUR, HOWEVER, [THAT THEY SERVE AS CONNECTIVES] IF THEY COME INTO CONTACT WITH OTHER KINDS OF UNCLEANNESS, WHETHER THEY BE OF MINOR10 OR MAJOR GRADES.11 MISHNAH 2. IF ONE HAD COLLECTED PIECES OF DOUGH-OFFERING NOT WITH THE INTENTION OF SEGREGATING THEM AFTERWARDS, OR A BATTER-CAKE THAT HAD BEEN BAKED ON ANOTHER AFTER A CRUST HAD FORMED IN THE OVEN,12 OR A FROTH HAD APPEARED IN THE WATER PRIOR TO ITS BUBBLING UP, OR THE SECOND SCUM THAT APPEARED IN THE BOILING OF GROATS OF BEANS, OR THE SCUM OF OLD WINE, OR THAT OF OIL OF ALL KINDS,13 OR OF LENTILS (R. -

Blogging Rav Lichtenstein

BLOGGING RAV LICHTENSTEIN A JOURNEY THROUGH A GIANT’S WRITINGS AS THE SERIES ORIGINALLY APPEARED ON TORAHMUSINGS.COM by GIDON ROTHSTEIN Please note that throughout the text, RA”L, Rav Lichtenstein and R. Lichtenstein all refer to Rabbi Dr. Aharon Lichtenstein zt”l. Blogging Rav Lichtenstein: A Journey Through a Giant’s Writings © 2016 Gidon Rothstein. All Rights Reserved. Blogging Rav Lichtenstein INTRODUCTION AND INVITATION This past Rosh Chodesh Iyyar, the world of Torah and avodat Hashem lost a giant, mori ve-rabi R. Aharon I in ,ואני בעניי ,Lichtenstein. Many people are taking on important acts and learning projects in his memory my limited capabilities, wanted to join in that. The idea that came to me was to review R. Lichtenstein z”l’s published volumes. While he wrote more than many realize (here’s the bibliography), there are, as far as I know, thirteen books he wrote or that were based on his talks. Eight of those are notes on shiurim he gave at Yeshivat Har Etzion, one is a collection, Minchat Aviv, of articles he published, and four volumes (By His Light, two volumes of Leaves of Faith, and Varieties of Religious Experience) collect English language talks he gave or articles he wrote. As I try to review for myself some of the fruit of R. Lichtenstein’s toiling and tilling in the garden of Torah, I hope to share one stimulating idea a week. I make no pretense that I will be comprehensive, will capture all or a representative sample of what is found in those works, only that I can, in a few hundred words, share a thought worth knowing. -

Jewishness, Birth and Giyyur

1 Zvi Zohar All Jews are Jews by Birth Biblical and Rabbinic Judaism agree, that anyone born to the appropriate Jewish parent – is Jewish. To most Jews, it sounds quite reasonable for Jewishness to derive from birth. However, such a determination is far from self-evident. Consider a counter-example: if a person was born on a kibbutz, and her two parents are members of the kibbutz, she is not automatically a member. Rather, upon reaching a certain age, she must decide if she wishes to apply for membership. If she applies, her application comes up for discussion by the kibbutz assembly, who then decide the matter by a vote. While it is reasonable to assume that a child born and grown on the kibbutz will be accepted for membership if she applies, it is not automatic. The important point (in the current context) is, that her membership is contingent upon at least two decisions: her decision to apply, and the assembly’s decision to accept her. In contrast, Jewishness is not contingent upon any person’s decision, but is regarded by tradition as a ‘fact of birth’. The sources of this self-understanding are very ancient: in the Bible, the Israelites are the “Children of Israel”, i.e., the lineal descendents of the Patriarch Jacob and his twelve sons. In the bible, then, the People of Israel are made up of persons born into a (very) extended family. Some notions accepted in Biblical times were abrogated or modified by the Oral Torah (Torah she- b’al peh); significantly, the concept of the familial nature of Jewishness was not only retained, but also even reinforced. -

Synagogue Emanu-El Scroll Shabbat Schedule Passover Service Schedule

Synagogue1 Emanu-El Scroll April 1-30, 2019 25 Adar II-25 Nisan 5779 Passover Service Schedule Erev Pesach: Pesach Day 5: Friday, April 19th Wednesday, April 24th 7:00AM – Minyan & Siyum 7:00AM – Minyan Shabbat Schedule Bekhorot (First-born “fast”) 5:30PM – Minyan 6:00PM – Kabbalat Shabbat Pesach Day 6: Shabbat Tazria/HaHodesh/ Rosh Hodesh Pesach Day 1: Thursday, April 25th Saturday, April 20th 7:00AM – Minyan Friday, April 5th 9:00AM – Macaroons & D’rash 5:30PM – Healing Service Candle-Lighting: 5:59PM Kabbalat Shabbat: 6:00PM (Men’s Club 9:30AM – Services Pesach Day 7: Shabbat & Dinner, Chagigat Siddur) Pesach Day 2: Friday, April 26th Saturday, April 6th Sunday, April 21st 9:30AM – Yom Tov Service Danish & D’rash: 9:00AM 9:30AM – Services 6:00PM – Kabbalat Shabbat Services: 9:30AM (JNF Shabbat) Pesach Day 3: Pesach Day 8: Shabbat Ends: 7:08PM Shabbat Metzora/HaGadol Monday, April 22nd Saturday, April 27th 7:00AM – Minyan 9:00AM – Macaroons & D’rash Friday, April 12th 5:30PM – Minyan 9:30AM – Yom Tov service Kabbalat Shabbat: 7:00PM, at The Village at Summerville, 201 W. 9th N St. (no Pesach Day 4: WITH YIZKOR services at Emanu-El) Tuesday, April 23rd (MEMORIAL PRAYERS) Candle-Lighting: 6:04PM 7:00AM – Minyan Saturday, April 13th 5:30PM – Minyan Danish & D’rash: 9:00AM Services: 9:30AM (Samuel Steinberg 2nd Bar Mitzvah, Anniversary Shabbat) Shabbat Ends: 7:13PM Shabbat Pesach Day 1 Friday, April 19th Kabbalat Shabbat, 6:00PM Candle-Lighting: 7:10PM Saturday, April 20th Macaroons & D’rash: 9:00AM Services: 9:30AM Shabbat Ends: 8:18PM Shabbat Pesach Day 8 Friday, April 26th Kabbalat Shabbat, 6:00PM Candle-Lighting: 7:15PM Saturday, April 27th Macaroons & D’rash: 9:00AM Services WITH YIZKOR: 9:30AM (Holocaust Torah Rededication, Chagigat Shema, Jr. -

Violent Video Games, but It Does Indicate What Happens When Children Make Media the Center of Their Lives

1 Violent and Defamatory Video Games Rabbi Elliot Dorff and Rabbi Joshua Hearshen February 4, 2010 EH 21:1.2010 This paper was approved on February 4, 2010, by a vote of twelve in favor (12-0-1). Voting in favor: Rabbis Kassel Abelson, Miriam Berkowitz, Elliot Dorff, Robert Fine, Susan Grossman, Josh Heller, Jane Kanarek, Daniel Nevins, Avram Reisner, Jay Stein, Steven Wernick and David Wise. Abstaining: Rabbi Adam Kligfeld. The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly provides guidance in matters of halakhah for the Conservative movement. The individual rabbi, however, is the authority for the interpretation and application of all matters of halakhah. She’elah: May Jews play violent or defamatory video games? Te’shuvah: The video game industry accounts for an enormous percentage of the entertainment industry today. 1 According to a September 2008 survey by the Pew Research Center, 97% of all teenagers play video games in some format. 2 While First Amendment rights to free speech assure that the content of these games is legal in American law, their ethical status varies widely. The variety of games available today is great, and the good to be gained from many of them may also be great. They stimulate the minds of the elderly, and they raise preparedness scores of those about to enter the Israeli army, and they help youngsters learn everything from music to mathematics. In a portion of the games, however, the material is morally questionable and may even be harmful or immoral on other grounds. These include what we are calling “violent and defamatory games.” By “violent” we mean gratuitous brute force intended 1 http://www.mediafamily.org the Mediawise Video Game Report Card is published periodically by the National Institute on Media and the Family. -

Delay of Pidyon Haben

YD 305:ll.l995 DELAY OF PIDYON HABEN Rabbi Vernon H. Kurtz TI1is paper was approved by the ens on March 27, 799,5, by a vote of' twenty in favor (20-0-0), Voting· infiwor: Rabbis Kassel Abelson, Tlen Zion Tlergman, Stephanie Dickstein, F:Zliot ;Y Dorff, Jerome ;l;f F:pstein, Myron S. Geller, Arnold wr Goodman, Su,l(lfl. Crossman, Judah Kogen, Ti?mon H. Kurtz, 4lan Tl. Lucas, Aaron T,. Machlet; Lionel F:. Moses, Paul Plothin, .:'Hu:)WT HabinotDitz, Arram Israel Hei.sne1", Joel f~·. Hembaum, Joel Hoth, Gerald Sholnili, and Gendd Xehzer. 17w Committee on Jm:ish T,aw and StandarcLs rijthe Rabbinical 1ssembly provides guidance in matters rijhalahhahfor the Conservative movement. 1he individual rabbi, hou,ever, is the authori('yJOr the interpretation and application of all malters of'lwluhhnh. May Pi111'i!:l be postponed beyond the thirty-first day'? One of my tasln; in my current congregation is to teach a life cycle class to students of m:.:~ n:::l/i:::l age and their parents. One of the topics discussed is T:::li1 P'i!:l, the redemp tion of the first-born son. Most students and many parents are unfamiliar with the con cept and the ritual. Over the course of six y<:ars teaching the class, two families have approached me and recognized that their son should have been redeemed, but was not. In each case, since the m~m remained the re;;ponsibility of the parent;; until their son became am:.:~ i:::l, we arranged for the ritual to take place. -

Mishnah 1: If Two Women Each Made a Qab1 and They Touched One Another, Even If They Are of the Same Kind They Are Exempt

'ΪΓ3Ί pD D*tM TIU; v>3>3 ID rip ΓΙ* IVJJ·) ΨΨ i^V Ο'ψί >ΓΙψ :N fl)VÖ (fol. 59c) .moa ύ>»ι Ν'^ψι n»n ρ« ΠΠΝ nwN>\y "irw ijppi .p-no? inis Mishnah 1: If two women each made a qab1 and they touched one another, even if they are of the same kind they are exempt. But if both belong to the same woman and are of the same kind they are obligated2, different kinds3 are exempt. 5 1 They separately made bread are obligated since 2 > /4. dough and now are baking it together 2 If the doughs touch or are on in the same oven. Separately, the the same baking sheet. doughs are exempt but both together 3 This is defined in Mishnah 4:2. ηψκ Drip ·)3ηί> -ION .'^Ό D>\M >ΓΙψ :N (fol. 59d) rmiN wy rii?po ΠΠΝ Π\ΙΪΝ on ni-papo ο?ηψ JTj?p)o nj>N ηηκ π^ν on .πηΝ ηψΝ? oriiN wy πίτ?^ ο>ψ3 >jw .o>\w >ri\y? Dip» TÖ D3V .ΓΐίΟίρρ ΠΓΐίΜ ΓΙψίν Ν1Π ΐ\ΥΪ) Π13ρ» iniN η'ψίν Nin·) wibb oip)? tö γρπ ddp n>ri>>o .vytob >Γΐψ πη ί»κ JTjapjo ii'p-! 'pi τπ?Ρ2 ηίηίρρ .nisin I^SN ">? ^»ψ ,D>\M 'Γΐψ3 piiN Vwy riiv>i Halakhah 1: "Two women who each made," etc. Rebbi Johanan said, usually for women, one does not mind, two do mind4. They gave to one woman who minds5 the status of two women, to two women who do not mind the status of one woman. -

Derech Hateva 2018.Pub

Derech HaTeva A Journal of Torah and Science A Publication of Yeshiva University, Stern College for Women Volume 22 2017-2018 Co-Editors Elana Apfelbaum | Tehilla Berger | Hannah Piskun Cover & Layout Design Shmuel Ormianer Printing Advanced Copy Center, Brooklyn, NY 11230 Acknowledgements The editors of this year’s volume would like to thank Dr. Harvey Babich for the incessant time and effort that he devotes to this journal. Dr. Babich infuses his students with a passion for the Torah Umadda vision and serves as an exemplar of this philosophy to them. Through his constant encouragement and support, students feel confident to challenge themselves and find interesting connections between science and Torah. Dr. Babich, thank you for all the effort you contin- uously devote to us through this journal, as well as to our personal and future lives as professionals and members of the Jewish community. The publication of Volume 22 of this journal was made possible thanks to the generosity of the following donors: Dr. and Mrs. Harvey Babich Mr. and Mrs. Louis Goldberg Dr. Fred and Dr. Sheri (Rosenfeld) Grunseid Rabbi and Mrs. Baruch Solnica Rabbi Joel and Dr. Miriam Grossman Torah Activities Council YU Undergraduate Admissions We thank you for making this opportunity possible. Elana Apfelbaum Tehilla Berger Hannah Piskun Dedication We would like to dedicate the 22nd volume of Derech HaTeva: A Journal of Torah and Science to the soldiers of the Israel Defence Forces (IDF). Formed from the ashes of the Holocaust, the Israeli army represents the enduring strength and bravery of the Jewish people. The soldiers of the IDF have risked their lives to protect the Jewish nation from adversaries in every generation in wars such as the Six-Day War and the Yom Kippur War. -

The Sea of Talmud: a Brief and Personal Introduction

Touro Scholar Lander College of Arts and Sciences Books Lander College of Arts and Sciences 2012 The Sea of Talmud: A Brief and Personal Introduction Henry M. Abramson Touro College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://touroscholar.touro.edu/lcas_books Part of the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Abramson, H. M. (2012). The Sea of Talmud: A Brief and Personal Introduction. Retrieved from https://touroscholar.touro.edu/lcas_books/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Lander College of Arts and Sciences at Touro Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Lander College of Arts and Sciences Books by an authorized administrator of Touro Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SEA OF TALMUD A Brief and Personal Introduction Henry Abramson Published by Parnoseh Books at Smashwords Copyright 2012 Henry Abramson Cover photograph by Steven Mills. No Talmud volumes were harmed during the photo shoot for this book. Smashwords Edition, License Notes This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment and information only. This ebook should not be re-sold to others. Educational institutions may reproduce, copy and distribute this ebook for non-commercial purposes without charge, provided the book remains in its complete original form. Version 3.1 June 18, 2012. To my students All who thirst--come to the waters Isaiah 55:1 Table of Contents Introduction Chapter One: Our Talmud Chapter Two: What, Exactly, is the Talmud? Chapter Three: The Content of the Talmud Chapter Four: Toward the Digital Talmud Chapter Five: “Go Study” For Further Reading Acknowledgments About the Author Introduction The Yeshiva administration must have put considerable thought into the wording of the hand- lettered sign posted outside the cafeteria. -

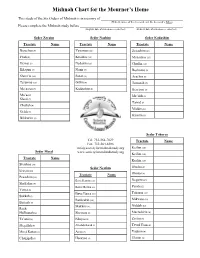

English Mishnah Chart

Mishnah Chart for the Mourner’s Home This study of the Six Orders of Mishnah is in memory of (Hebrew names of the deceased, and the deceased’s father) Please complete the Mishnah study before (English date of shloshim or yahrtzeit ) (Hebrew date of shloshim or yahrtzeit ) Seder Zeraim Seder Nashim Seder Kodashim Tractate Name Tractate Name Tractate Name Berachos (9) Yevamos (16) Zevachim (14) Peah (8) Kesubos (13) Menachos (13) Demai (7) Nedarim (11) Chullin (12) Kilayim (9) Nazir (9) Bechoros (9) Shevi’is (10) Sotah (9) Arachin (9) Terumos (11) Gittin (9) Temurah (7) Ma’asros (5) Kiddushin (4) Kereisos (6) Ma’aser Me’ilah (6) Sheni (5) Tamid (7) Challah (4) Middos (5) Orlah (3) Kinnim (3) Bikkurim (3) Seder Tohoros Tel: 732-364-7029 Tractate Name Fax: 732-364-8386 [email protected] Keilim (10) Seder Moed www.societyformishnahstudy.org Keilim (10) Tractate Name Keilim (10) Shabbos (24) Seder Nezikin Oholos (9) Eruvin (10) Tractate Name Oholos (9) Pesachim (10) Bava Kamma (10) Negaim (14) Shekalim (8) Bava Metzia (10) Parah (12) Yoma (8) Bava Basra (10) Tohoros (10) Sukkah (5) Sanhedrin (11) Mikvaos (10) Beitzah (5) Makkos (3) Niddah (10) Rosh HaShanah (4) Shevuos (8) Machshirin (6) Ta’anis (4) Eduyos (8) Zavim (5) Megillah (4) Avodah Zarah (5) Tevul Yom (4) Moed Kattan (3) Avos (5) Yadaim (4) Chagigah (3) Horayos (3) Uktzin (3) • Our Sages have said that Asher, son of the Patriarch Jacob sits at the opening to Gehinom (Purgatory), and saves [from entering therein] anyone on whose behalf Mishnah is being studied . -

Judges) “In All Your Gates” That They Are to Judge the People with Righteous Judgment

בייה PORTION DATE HEB DATE TORAH NEVIIM RENEWED Shoftim 18 Aug. 2018 7 Elul 5778 Deut. 16:18-21:9 Isa. 51:12-52:12 John 14:9-20 This week’s Torah portion starts with the qualification of shoftim (judges) “in all your gates” that they are to judge the people with righteous judgment. The Torah then describes how they are to judge against the accused. The Midrash questions the eligibility of judges. The immediate family of litigants are disqualified to judge as well as they are ineligible to testify as said, “The ahvot (fathers) shall not be put to death for the children, neither shall the children be put to death for the ahvot.” (Deut. 24:16) The Gemara interprets: fathers shall not be executed because of the testimony of sons, and vice versa.1 Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel (10 BCE-70 CE) said: Do not make light of justice, for it is one of the three legs of the world: justice, truth, and on peace. Therefore, we are to be mindful of not perverting justice as “you can cause the world to shake2 for it (justice) is one of the legs of Hashem’s Throne of Glory. “Righteousness and justice are the foundation of Your throne.” (Psa 85:15) The Proverbs 6:6-8 says, “Go to the ant, you lazy one; consider her halachot, and be wise: They have no guide, overseer, or ruler, yet she; Provides her food in the and gathers her food in the harvest.” The sages teach the ants has three stories in its home.