Violent Video Games, but It Does Indicate What Happens When Children Make Media the Center of Their Lives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cinema Recognizing Making Intimacy Vincent Tajiri Even Hotter!

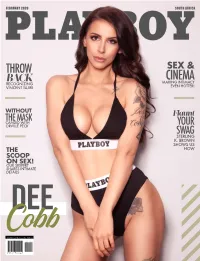

FEBRUARY 2020 SOUTH AFRICA THROW SEX & BACK CINEMA RECOGNIZING MAKING INTIMACY VINCENT TAJIRI EVEN HOTTER! WITHOUT Flaunt THE MASK CANDID WITH YOUR ORVILLE PECK SWAG STERLING K. BROWN SHOWS US THE HOW SCOOP ON SEX! OUR SEXPERT SHARES INTIMATE DETAILS Dee Cobb WWW.PLAYBOY.CO.ZA R45.00 20019 9 772517 959409 EVERY. ISSUE. EVER. The complete Playboy archive Instant access to every issue, article, story, and pictorial Playboy has ever published – only on iPlayboy.com. VISIT PLAYBOY.COM/ARCHIVE SOUTH AFRICA Editor-in-Chief Dirk Steenekamp Associate Editor Jason Fleetwood Graphic Designer Koketso Moganetsi Fashion Editor Lexie Robb Grooming Editor Greg Forbes Gaming Editor Andre Coetzer Tech Editor Peter Wolff Illustrations Toon53 Productions Motoring Editor John Page Senior Photo Editor Luba V Nel ADVERTISING SALES [email protected] for more information PHONE: +27 10 006 0051 MAIL: PO Box 71450, Bryanston, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2021 Ƶč%./0(++.ǫ(+'ć+1.35/""%!.'Čƫ*.++/0.!!0Ē+1.35/ǫ+1(!2. ČĂāĊā EMAIL: [email protected] WEB: www.playboy.co.za FACEBOOK: facebook.com/playboysouthafrica TWITTER: @PlayboyMagSA INSTAGRAM: playboymagsa PLAYBOY ENTERPRISES, INTERNATIONAL Hugh M. Hefner, FOUNDER U.S. PLAYBOY ǫ!* +$*Čƫ$%!"4!10%2!þ!. ƫ++,!.!"*!.Čƫ$%!"ƫ.!0%2!þ!. Michael Phillips, SVP, Digital Products James Rickman, Executive Editor PLAYBOY INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHING !!*0!(Čƫ$%!"ƫ+))!.%(þ!.Ē! +",!.0%+*/ Hazel Thomson, Senior Director, International Licensing PLAYBOY South Africa is published by DHS Media House in South Africa for South Africa. Material in this publication, including text and images, is protected by copyright. It may not be copied, reproduced, republished, posted, broadcast, or transmitted in any way without written consent of DHS Media House. -

The Agency and Hilton & Hyland List Playboy Mansion for $200 Million

prnewswire.com http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/the-agency-and-hilton--hyland-list-playboy-mansion-for-200-million-300201987.html The Agency And Hilton & Hyland List Playboy Mansion For $200 Million One of America's Most Famous Addresses, Known for Legendary Parties and Lavish Lifestyle Hits the Market Playboy Enterprises, Inc. BEVERLY HILLS, Calif., Jan. 11, 2016 /PRNewswire/ -- The Agency and Hilton & Hyland announced today the listing of the Playboy Mansion for $200 million. The principal agents are Drew Fenton and Gary Gold of Hilton & Hyland and Mauricio Umansky of The Agency. "This is the right time to seek a buyer for this incredible property who understands the role the Mansion has played for our brand and enables us to continue to reinvest in the transformation of our business," said Playboy Enterprises CEO, Scott Flanders. "The Playboy Mansion has been a creative center for Hef as his residence and workplace for the past 40 years, as it will continue to be if the property is sold." The crown jewel of L.A.'s "Platinum Triangle" situated on 5 picturesque acres in Holmby Hills, The Playboy Mansion is a nearly 20,000 square foot residence that is both an ultra-private retreat and the ultimate setting for large-scale entertaining. The Mansion features 29 rooms and every amenity imaginable, including a catering kitchen, wine cellar, home theater, separate game house, gym, tennis court and freeform swimming pool with a large, cave-like grotto. The property also features a four-bedroom guest house. In addition, the Playboy Mansion is one of a select few private residences in L.A. -

Stephen Hawking,These Are the Women in Scien

The Queen’s commonwealth Day Message 2021 The Queen’s commonwealth Day Message 2021: Over the coming week, as we celebrate the friendship, spirit of unity and achievements of the Commonwealth, we have an opportunity to reflect on a time like no other. Whilst experiences of the last year have been different across the Commonwealth, stirring examples of courage, commitment and selfless dedication to duty have been demonstrated in every Commonwealth nation and territory, notably by those working on the front line who have been delivering health care and other public services in their communities. We have also taken encouragement from remarkable advances in developing new vaccines and treatments. The testing times experienced by so many have led to a deeper appreciation of the mutual support and spiritual sustenance we enjoy by being connected to others. The need to maintain greater physical distance, or to live and work largely in isolation, has, for many people across the Commonwealth, been an unusual experience. In our everyday lives, we have had to become more accustomed to connecting and communicating via innovative technology – which has been new to some of us – with conversations and communal gatherings, including Commonwealth meetings, conducted online, enabling people to stay in touch with friends, family, colleagues, and counterparts who they have not been able to meet in person. Increasingly, we have found ourselves able to enjoy such communication, as it offers an immediacy that transcends boundaries or division, helping any sense of distance to disappear. We have all continued to appreciate the support, breadth of experiences and knowledge that working together brings, and I hope we shall maintain this renewed sense of closeness and community. -

A USER's MANUAL Part 1: How Is Halakhah Organized?

TORAHLEADERSHIP.ORG RABBI ARYEH KLAPPER HALAKHAH: A USER’S MANUAL Part 1: How is Halakhah Organized? I. How is Halakhah Organized? 4 case studies a. Mishnah Berakhot 1:1, and gemara thereupon b. Support of the poor Peiah, Bava Batra, Matnot Aniyyim, Yoreh Deah) c. Conversion ?, Yevamot, Issurei Biah, Yoreh Deah) d. Mourning Moed Qattan, Shoftim, Yoreh Deiah) Mishnah Berakhot 1:1 From what time may one recite the Shema in the evening? From the hour that the kohanim enter to eat their terumah Until the end of the first watch, in the opinion of Rabbi Eliezer. The Sages say: Until midnight. Rabban Gamliel says: Until morning. It happened that his sons came from a wedding feast. They said to him: We have not yet recited the Shema. He said to them: If it has not yet morned, you are obligated to recite it. Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 2a What is the context of the Mishnah’s opening “From when”? Also, why does it teach about the evening first, rather than about the morning? The context is Scripture saying “when you lie down and when you arise” (Devarim 6:7, 11:9). what the Mishnah intends is: “The time of the Shema of lying-down – when is it?” Alternatively: The context is Creation, as Scripture writes “There was evening and there was morning”. Mishnah Berakhot 1:1 (continued) Not only this – rather, everything about which the Sages say until midnight – their mitzvah is until morning. The burning of fats and organs – their mitzvah is until morning. All sacrifices that must be eaten in a day – their mitzvah is until morning. -

The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿavoda Zara By

The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿAvoda Zara By Mira Beth Wasserman A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley in Jewish Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Daniel Boyarin, chair Professor Chana Kronfeld Professor Naomi Seidman Professor Kenneth Bamberger Spring 2014 Abstract The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿAvoda Zara by Mira Beth Wasserman Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel Boyarin, chair In this dissertation, I argue that there is an ethical dimension to the Babylonian Talmud, and that literary analysis is the approach best suited to uncover it. Paying special attention to the discursive forms of the Talmud, I show how juxtapositions of narrative and legal dialectics cooperate in generating the Talmud's distinctive ethics, which I characterize as an attentiveness to the “exceptional particulars” of life. To demonstrate the features and rewards of a literary approach, I offer a sustained reading of a single tractate from the Babylonian Talmud, ʿAvoda Zara (AZ). AZ and other talmudic discussions about non-Jews offer a rich resource for considerations of ethics because they are centrally concerned with constituting social relationships and with examining aspects of human experience that exceed the domain of Jewish law. AZ investigates what distinguishes Jews from non-Jews, what Jews and non- Jews share in common, and what it means to be a human being. I read AZ as a cohesive literary work unified by the overarching project of examining the place of humanity in the cosmos. -

Speaker Materials

Speaker Materials Partnering organizations: The Akdamut – an Aramaic preface to our Torah Reading Rabbi Gesa S. Ederberg ([email protected]) ַאְקָדּמוּת ִמִלּין ְוָשָׁריוּת שׁוָּת א Before reciting the Ten Commandments, ַאְוָלא ָשֵׁקְלָא ַהְרָמןְוּרשׁוָּת א I first ask permission and approval ְבָּבֵבי ְתֵּרי וְּתַלת ְדֶאְפַתְּח בּ ַ ְקשׁוָּת א To start with two or three stanzas in fear ְבָּבֵרְי דָבֵרי ְוָטֵרי ֲעֵדי ְלַקִשּׁישׁוָּת א Of God who creates and ever sustains. ְגּבָוּרן ָעְלִמין ֵלהּ ְוָלא ְסֵפק ְפִּרישׁוָּת א He has endless might, not to be described ְגִּויל ִאְלּוּ רִקיֵעי ְק ֵ ָי כּל חְוּרָשָׁת א Were the skies parchment, were all the reeds quills, ְדּיוֹ ִאלּוּ ַיֵמּי ְוָכל ֵמיְכִישׁוָּת א Were the seas and all waters made of ink, ָדְּיֵרי ַאְרָעא ָסְפֵרי ְוָרְשֵׁמַי רְשָׁוָת א Were all the world’s inhabitants made scribes. Akdamut – R. Gesa Ederberg Tikkun Shavuot Page 1 of 7 From Shabbat Shacharit: ִאלּוּ פִ יוּ מָ לֵא ִשׁיָרה ַכָּיּ ם. וּלְשׁו ֵוּ ִרָנּה כַּהֲמון גַּלָּיו. ְושְפתוֵתיוּ ֶשַׁבח ְכֶּמְרֲחֵבי ָ רִקיַע . וְעֵיֵיוּ ְמִאירות ַכֶּשֶּׁמ שׁ ְוַכָיֵּרַח . וְ יָדֵ יוּ פְ רוּשות כְּ ִ ְשֵׁרי ָשָׁמִי ם. ְוַרְגֵליוּ ַקלּות ָכַּאָיּלות. ֵאין אֲ ַ ְחוּ ַמְסִפּיִקי ם לְהודות לְ ה' אֱ להֵ יוּ וֵאלהֵ י ֲאבוֵתיוּ. וְּלָבֵר ֶאת ְשֶׁמ עַל ַאַחת ֵמֶאֶלף ַאְלֵפי אֲלָ ִפי ם ְוִרֵבּי ְרָבבות ְפָּעִמי ם Were our mouths filled with song as the sea, our tongues to sing endlessly like countless waves, our lips to offer limitless praise like the sky…. We would still be unable to fully express our gratitude to You, ADONAI our God and God of our ancestors... Akdamut – R. Gesa Ederberg Tikkun Shavuot Page 2 of 7 Creation of the World ֲהַדר ָמֵרי ְשַׁמָיּא ְו ַ שׁ ִלְּיט בַּיֶבְּשָׁתּ א The glorious Lord of heaven and earth, ֲהֵקים ָעְלָמא ְיִחָידאי ְוַכְבֵּשְׁהּ בַּכְבּשׁוָּת א Alone, formed the world, veiled in mystery. -

(Kita Zayin) Curriculum Updated: July 24, 2014

7th Grade (Kita Zayin) Curriculum Updated: July 24, 2014 7th Grade (Kita Zayin) Curriculum Rabbi Marcelo Kormis 30 Sessions Notes to Parents: This curriculum contains the knowledge, skills and attitude Jewish students are expected to learn. It provides the learning objectives that students are expected to meet; the units and lessons that teachers teach; the books, materials, technology and readings used in a course; and the assessments methods used to evaluate student learning. Some units have a large amount of material that on a given year may be modified in consideration of the Jewish calendar, lost school days due to weather (snow days), and give greater flexibility to the teacher to accommodate students’ pre-existing level of knowledge and skills. Page 1 of 16 7th Grade (Kita Zayin) Curriculum Updated: July 24, 2014 Part 1 Musaguim – A Vocabulary of Jewish Life 22 Sessions The 7th grade curriculum will focus on basic musaguim of Jewish life. These musaguim cover the different aspects and levels of Jewish life. They can be divided into 4 concentric circles: inner circle – the day of a Jew, middle circle – the week of a Jew, middle outer circle – the year of a Jew, outer circle – the life of a Jew. The purpose of this course is to teach students about the different components of a Jewish day, the centrality of the Shabbat, the holidays and the stages of the life cycle. Focus will be placed on the Jewish traditions, rituals, ceremonies, and celebrations of each concept. Lifecycle events Jewish year Week - Shabbat Day Page 2 of 16 7th Grade (Kita Zayin) Curriculum Updated: July 24, 2014 Unit 1: The day of a Jew: 6 sessions, 45 minute each. -

Daf Ditty Pesachim 78: Korban Pesach Today (?)

Daf Ditty Pesachim 78: Korban Pesach today (?) Three girls in Israel were detained by the Israeli Police (2018). The girls are activists of the “Return to the Mount” (Chozrim Lahar) movement. Why were they detained? They had posted Arabic signs in the Muslim Quarter calling upon Muslims to leave the Temple Mount area until Friday night, in order to allow Jews to bring the Korban Pesach. This is the fourth time that activists of the movement will come to the Old City on Erev Pesach with goats that they plan to bring as the Korban Pesach. There is also an organization called the Temple Institute that actively is trying to bring back the Korban Pesach. It is, of course, very controversial and the issues lie at the heart of one of the most fascinating halachic debates in the past two centuries. 1 The previous mishnah was concerned with the offering of the paschal lamb when the people who were to slaughter it and/or eat it were in a state of ritual impurity. Our present mishnah is concerned with a paschal lamb which itself becomes ritually impure. Such a lamb may not be eaten. (However, we learned incidentally in our study of 5:3 that the blood that gushed from the lamb's throat at the moment of slaughter was collected in a bowl by an attendant priest and passed down the line so that it could be sprinkled on the altar). Our mishnah states that if the carcass became ritually defiled, even if the internal organs that were to be burned on the altar were intact and usable the animal was an invalid sacrifice, it could not be served at the Seder and the blood should not be sprinkled. -

Women's Testimony and Talmudic Reasoning

Kedma: Penn's Journal on Jewish Thought, Jewish Culture, and Israel Volume 2 Number 2 Fall 2018 Article 8 2020 Women’s Testimony and Talmudic Reasoning Deena Kopyto University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/kedma Part of the Jewish Studies Commons, Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, and the Religion Commons This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/kedma/vol2/iss2/8 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Women’s Testimony and Talmudic Reasoning Creative Commons License This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License This article is available in Kedma: Penn's Journal on Jewish Thought, Jewish Culture, and Israel: https://repository.upenn.edu/kedma/vol2/iss2/8 Women’s Testimony and Talmudic Reasoning Deena Kopyto Introduction Today, being a witness is often considered a burden – an obligation that courts force people to fulfill. In contrast, in Talmudic-era Babylonia and ancient Israel, testifying was a privilege that certain groups, including slaves, women, and children, did not enjoy. While minors should be barred from participating in courts, and still largely are today, the status of women in Talmudic courts poses a much trickier question. Through this historical and Talmudic analysis, I aim to determine the root of this ban. The reasons for the ineligibility of female testimony range far and wide, but most are not explicitly mentioned in the Talmud. Perhaps women in Talmudic times were infrequently called as witnesses, and rabbis banned women from participation in courts in order to further crystallize this patriarchal structure. -

Jewishness, Birth and Giyyur

1 Zvi Zohar All Jews are Jews by Birth Biblical and Rabbinic Judaism agree, that anyone born to the appropriate Jewish parent – is Jewish. To most Jews, it sounds quite reasonable for Jewishness to derive from birth. However, such a determination is far from self-evident. Consider a counter-example: if a person was born on a kibbutz, and her two parents are members of the kibbutz, she is not automatically a member. Rather, upon reaching a certain age, she must decide if she wishes to apply for membership. If she applies, her application comes up for discussion by the kibbutz assembly, who then decide the matter by a vote. While it is reasonable to assume that a child born and grown on the kibbutz will be accepted for membership if she applies, it is not automatic. The important point (in the current context) is, that her membership is contingent upon at least two decisions: her decision to apply, and the assembly’s decision to accept her. In contrast, Jewishness is not contingent upon any person’s decision, but is regarded by tradition as a ‘fact of birth’. The sources of this self-understanding are very ancient: in the Bible, the Israelites are the “Children of Israel”, i.e., the lineal descendents of the Patriarch Jacob and his twelve sons. In the bible, then, the People of Israel are made up of persons born into a (very) extended family. Some notions accepted in Biblical times were abrogated or modified by the Oral Torah (Torah she- b’al peh); significantly, the concept of the familial nature of Jewishness was not only retained, but also even reinforced. -

Tanya Sources.Pdf

The Way to the Tree of Life Jewish practice entails fulfilling many laws. Our diet is limited, our days to work are defined, and every aspect of life has governing directives. Is observance of all the laws easy? Is a perfectly righteous life close to our heart and near to our limbs? A righteous life seems to be an impossible goal! However, in the Torah, our great teacher Moshe, Moses, declared that perfect fulfillment of all religious law is very near and easy for each of us. Every word of the Torah rings true in every generation. Lesson one explores how the Tanya resolved these questions. It will shine a light on the infinite strength that is latent in each Jewish soul. When that unending holy desire emerges, observance becomes easy. Lesson One: The Infinite Strength of the Jewish Soul The title page of the Tanya states: A Collection of Teachings ספר PART ONE לקוטי אמרים חלק ראשון Titled הנקרא בשם The Book of the Beinonim ספר של בינונים Compiled from sacred books and Heavenly מלוקט מפי ספרים ומפי סופרים קדושי עליון נ״ע teachers, whose souls are in paradise; based מיוסד על פסוק כי קרוב אליך הדבר מאד בפיך ובלבבך לעשותו upon the verse, “For this matter is very near to לבאר היטב איך הוא קרוב מאד בדרך ארוכה וקצרה ”;you, it is in your mouth and heart to fulfill it בעזה״י and explaining clearly how, in both a long and short way, it is exceedingly near, with the aid of the Holy One, blessed be He. "1 of "393 The Way to the Tree of Life From the outset of his work therefore Rav Shneur Zalman made plain that the Tanya is a guide for those he called “beinonim.” Beinonim, derived from the Hebrew bein, which means “between,” are individuals who are in the middle, neither paragons of virtue, tzadikim, nor sinners, rishoim. -

Torah Portion – Vayera

AVODAH: The Jewish Service Corps Torah Portion – Vayera Justice and Prayer SOURCE: Teach us rabbi: If I am riding along on a donkey and the time for prayer arrives, what should I do? This is what the Sages taught: If you are riding along on a donkey and the time for prayer arrives, dismount [and pray]. And if you cannot dismount because you are distracted by worries about the safety of the money you have in your baggage, or you are afraid for your safety, pray while you are riding. Rabbi Yohanan said: We learn from this teaching that a person should be mindful and undistracted during prayer before God. Abba Shaul said when a person prays with concentration and direction (kavanah), that person’s prayers will surely be answered, as it says, You will direct their mind and You will listen to their prayer… (Psalms 10:17) And nobody had kavanah in their prayer like our Father Abraham, which we see from the fact that he said: Far be it from you to do a thing like that! (Genesis 18:25) [Midrash Tanhuma, Hayyei Sarah #1] COMMENTARY: The prooftext for Abraham’s exemplary concentration and intention during prayer – his kavanah – is unusual, since it is not a verse from a prayer, but a verse from an argument that Abraham is having with God! Here is the full context: Then God said, “The outrage of Sodom and Gomorrah is so great, and their sin is so grave! I will go down and see whether they have acted altogether according to the outcry that has reached Me; if not, I will take note.” Then the men [who were visiting Abraham] went on from there to Sodom, while Abraham remained standing before God.